Gabi Ngcobo

Gabi Ngcobo. Photo: Masimba Sasa.

Gabi Ngcobo. Photo: Masimba Sasa.

To those familiar with the work of artist and curator Gabi Ngcobo, it is not surprising that We don't need another hero, the 10th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art (9 June–9 September 2018), resisted the desire for a single heroic conclusion. As the exhibition's curator, Ngcobo sought to create a 'multi-layered referential space' with its own evolving connections and alliances. Based in Johannesburg, where she teaches at the Wits School of Arts, Ngcobo deals with notions of decolonisation—looking for ways to transform normative understandings and definitions so as to reconfigure historical positions.

The task is not easy. Complex hierarchies and dominant forces—particularly, Western art—form the lenses through which art history was and is written. Ngcobo thus walks a fine line, trying to overcome normative terms like 'postcolonial' while using the tools created by this field of study in her work so that art from regions beyond the West can be seen—first and foremost—as art, and only secondly through the lens of geographical and ethnic identity. Resisting powerful narratives while engaging them in order to make possible regains, Ngcobo's hybrid practice allows for the creation of zones of ideological entanglement. She considers the political landscape in which her curatorial practice unfolds, and creates ways of speaking about art in response.

Ngcobo is also an artist and facilitator within collaborative platforms such as the Center for Historical Reenactments (CHR), which she co-founded in 2010. (She sees all her roles forming an interconnected whole.) The CHR explores how historical traditions in contemporary art are developed and dispatched. In 2014, the platform participated in the 8th Berlin Biennale (29 May–3 August 2014) with the installation Digging Our Own Graves 101 (2014), which explored questions surrounding land rights in South Africa, in order to 'occupy a space of memory' and 'stage a return to what has been buried'. The work involved talks by Ngcobo, Kemang Wa Lehulere, Michelle Monareng, and Sinethemba Twalo, and the production of a limited-edition newspaper, DOOG101, featuring essay excerpts by Nkule Mabaso, Nomusa Makhubu, and Achille Mbembe, among others.

In 2012, Ngcobo participated in Condition Report: Symposium on Building Art Institutions in Africa at Raw Material Company in Dakar, Senegal, whose long-term programme in 2014, 'Personal Liberties', saw Ngcobo work on a curatorial project in the form of a film called Causality Dilemmas: A Chronology of Human Feelings and Desires. The project involved research that Ngcobo conducted within the LGBTI community in Dakar, proposing 'a metaphysical studio and creative research lab' where participants could engage in developing a 'mind-map of human feelings and desires in Africa'. Before curating the 10th Berlin Biennale, Ngcobo was one of the co-curators for the 32nd Bienal de São Paulo: Incerteza Viva (Live Uncertainty) (7 September–11 December 2016) and A Labour of Love at Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt (3 December 2015–24 July 2016), which travelled to the Johannesburg Art Gallery between 14 August and 5 November 2017.

In this interview, which took place before the opening of the 10th Berlin Biennale, Ngcobo expands on some of the curatorial algorithms behind her much-anticipated exhibition.

MSIn Texte zur Kunst, you stated that terms like 'identity politics' and 'people politics' often tend to be deceiving and that they are also related to othering. As a South African artist, curator, and educator working with decolonial concepts in your practice, how have you circumvented the German public's labelling of the 10th Berlin Biennale exhibition as the 'Black Berlin Biennale'?

GNBlackness is a complex and impossible subject. It is also a subject and identity we are happy to take care of ourselves, as we evolve. For the 10th Berlin Biennale, we established codes that helped us navigate the questions you bring up. Take, for instance, our visual identity, which references the dazzle camouflage similar to that which was painted on warships in World War I, which we rendered in 'fictional' colours, greys and pinks, to represent histories and futures. These World War I warships were not camouflaged in order to be unseen, but rather to pose questions about the ways that they are seen—how fast, how big, which direction is a vessel heading? History tells us that the camouflaged ships were still attacked, perhaps more than those that were not camouflaged. This may mean, either way, 'even when we win, we gon' lose', to quote a line from Jay Z's 'Moonlight'.

MSThe international art world seems to jump from one theme or issue to another without ever really spending enough time on a particular subject—or context—to enable a lasting impact. What approach did you take when curating the 10th Berlin Biennale to ensure a permanent effect on how global contemporary art is conceived, supported, and circulated?

GNWe refuse to be a thematic exhibition, or one that is issue laden, which is why we insist that We don't need another hero is a position—perhaps an impossible one. It is a message to history, a message to the future, and therefore a way to stay comfortably with the things we cannot yet know.

MS

GNYou once likened your curatorial work to: 'contributing a drop of water on the mind river knowing that would help the river flow'. I read this as a poetic description of the fact that exhibition-making is a highly developed form of cognitive, neural, and phenomenological technology designed for the cultural and political transformation of the audience.

You have spoken about the 10th Berlin Biennale's objective as 'obscuring things in order to clarify them in a new way', noting how curatorial practice can actually produce positive knowledge. In what way does the Biennale offer a new approach to curating an international exhibition?

MS

GNFrom the beginning of this process we were very wary of promising to reinvent the curatorial wheel. In my collaborative practice, we have often experimented with forms that were true to the context from which we worked. In a way, one might consider these experimental forms 'new', more daring, or ungovernable. This was the case with the platform I co-founded in 2010, the Center for Historical Reenactments (CHR), and, to a certain degree, NGO – Nothing Gets Organised, which I co-founded in 2015.

Many of these forms are untranslatable and perhaps attempting to translate them in the Western context feels like one is initiating a war, even if one is invited to do so in the first place. The ungovernability I refer to is the idea that through these collaborative platforms we often work outside of 'rules', which we didn't create in the first place, only to find that those who adhere to these rules become uneasy when we begin to question or break them.

MSHow does it feel to curate a large international biennial exhibition as an artist?

GNI don't really know how it feels because I don't know how it feels to not do otherwise. Thinking and working between disciplines is my way of being in the world and the way I become part of the world. I studied art against many odds—many of which had to do with the political atmosphere I was born in and grew up under. Finding art was the beginning of an ongoing initiation process. I need to hold on to it, or else I fear I won't evolve. This position allows me to grab things with my own hands—not only with words or ideas—in order to shift something that refuses to yield or for which I have no words. Art is my curatorial weapon.

MS

GNEach venue that makes up this Berlin Biennale has a very specific curatorial trajectory. Akademie der Künste focuses on two heritage sites and one historical figure—the palace of Sanssouci, built in Potsdam between 1745 and 1747; the Sans-Souci Palace in Milot, Haiti; and the Haitian revolutionary leader, Colonel Jean-Baptiste Sans Souci. HAU Hebbel am Ufer presents research projects surrounding the Kwaito musical genre, which originated in the 1990s in South Africa. The show at KW Institute for Contemporary Art pays homage to institutions and personalities that have cultivated the international contemporary art scene in Berlin. Artists showing at ZK/U – Centre for Art and Urbanistics focus on the relationship between bodies and power systems that are built into the city environment; while the Volksbühne's glass pavilion is designated for durational events centred on the historical significance of the theatre.

What was your process for selecting these locations and how did you see these sub-themes feeding into your larger project?

MS

GNI prefer to think about these as starting points rather than focuses or themes. The work of Firelei Báez, for example, located at Akademie der Künste, brings forth questions about the 'production of history and systematic silencing of the past'.[1] Take the three Sans Soucis that this section of the show references: Sanssouci, a castle in Potsdam, Germany, built between 1745 and 1747 as a place of leisure for Frederick the Great; Sans-Souci Palace, a castle in Milot, Haiti, built between 1810 and 1813 for King Henri I of Haiti; and the Haitian colonel, Jean-Baptiste Sans-Souci, a prominent figure in the Haitian revolution. Báez's free-standing sculpture positions these moments in history in order to question hierarchies, processes of writing history, and the fictionalisation of historic events.

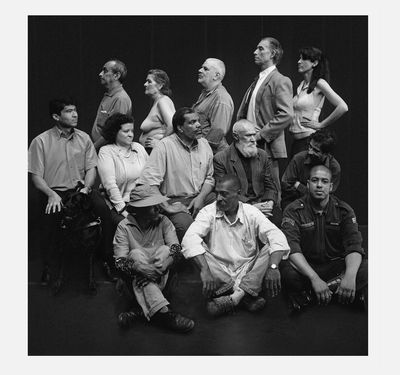

Looking for venues in Berlin is a complicated adventure. We decided quite early in the process on venues we wanted to use. There is the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, which is the home of the Berlin Biennale. It has its own histories, as well as a living archive of people who have moved on to other ventures, and those who are still part of the day-to-day functions of the institution. Cinthia Marcelle's series 'Legendaries' (2008–ongoing) engages with this history, which is also a history of post-wall Berlin. Through a consultative and selective process, 14 people representing KW/BB 'legendaries' were photographed on a Saturday afternoon. This work was the starting point of the exhibition at KW.

From there onwards, the exhibition went into different directions, at times coherently but other times not obviously so. The negotiations between different venues—what is permitted, what is impossible—became part of the curatorial process in one way or another.

The artist duo Las Nietas de Nonó, two sisters from Puerto Rico, present work at Berlin's historic Volksbühne, an institution that survived the division of the city and served the former East before reunification. Las Nietas de Nonó's practice is usually grounded in their own family lineage, and is heavily invested in the relationship between very intimate familial spaces and the abuse of power by larger, national, institutions. Their work recalls the necessity to think about the power of institutions to penetrate the most intimate areas of our lives.

Heba Y. Amin's Operation Sunken Sea (2018) at ZK/U plays with the megalomaniac idea of converging the European and African continent in order to utilise resources formerly invested in national interests, like subsidising terrorism or financing wars, and for more humanitarian purposes, like full employment and the fair distribution of goods. ZK/U is the appropriate environment for such an undertaking, because the artist-run space supports projects that allow for both thinking and praxis at the potent intersection of art, and architecture and urban studies. One of Amin's proposals is to build a canal between Berlin and Cape Town.

Finally, Kelektla! Library brings a new edition of its That'i Cover Okestra to the theatre and performance centre, HAU Hebbel am Ufer. This group of musicians, composers and music historians pays homage to the legacy of Kwaito, South Africa's eclectic music movement of the early 1990s. The genre gave the youth of South Africa a global sound invested with rich political, economic, and philosophical implications.

As one can see with these artists mentioned, they are automatically positioned in a conversation with the environments they are presenting their work in. It is fruitful to contemplate the histories of larger institutions and architectural spaces here in Berlin because it reminds us of the complexity of historiography and the multiple subjectivities enmeshed in it.

MSIn one interview, you said the word 'unlearning' is so overused that it's becoming a meaningless buzzword. How would you describe the differences between this idea of unlearning as it was framed by documenta 14, and the way you have dealt with existing knowledges in this Biennale?

GNWe have to accept the unknown and, more importantly, the fact that we cannot understand and comprehend everything immediately. It is actually very Western to believe that knowledge is instant and can be consumed right away. What is it that makes us so nervous if we cannot name and categorise new phenomena or curatorial models right away? It almost seems like we have to cultivate a practice of just being with art for a while before jumping into nervous and at times neurotic discussions about it. Language does not have to be available promptly. I think we should treat art as a space and experience that allows us the privilege to contemplate and endure the process of making new answers.—[O]

1. See: Michel-Ralph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston, MA: Beacon Press Books: 1995).