Grayson Perry

Grayson Perry, winner of the Turner Prize in 2003, is one of Britain's best-known contemporary artists. While he is most recognised for his alluring ceramics that chronicle contemporary life—drawing viewers in with their beauty, wit and exquisite craftsmanship, and then surprising with their often hard-hitting depictions—he has more recently started to create epic tapestries. This art form, often associated with historical notions of English aristocracy, Perry uses to elevate the daily dramas of modern British life. As with his ceramic work, the artist draws upon his own personal life, his observations of society, and history at large, to create highly detailed tapestries that explore issues from class and politics to sex and religion.

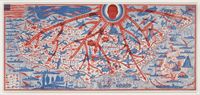

Perry’s newest work, Comfort Blanket

(2014) takes the form of a brightly coloured and richly patterned tapestry designed as a giant pound note. It features the bust of a smiling Queen, and numerous words and sayings associated with a type of ‘Britishness’. Perry has described this work as a portrait of Britain, saying it is partly inspired by a friend whose family had walked out of Hungary fleeing the Soviets in 1956 and whose mother referred to Britain as her ‘security blanket’.

Comfort Blanket follows on from the artist’s earlier work, The Walthamstow Tapestry (2009) and his tapestry series, The Vanity of Small Differences (2012). The Walthamstow Tapestry, a monumental 15-metre work, is now in the collection of the China Academy of Art, having been displayed at the Hangzhou Triennial in 2013. The work depicts a man’s passage from birth to death, a trajectory that is heavily scattered with brand names encountered on the way: an exploration of our almost fanatical and personality-defining obsession with brands.

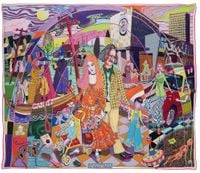

Likewise, The Vanity of Small Differences (2012) also interrogates questions of contemporary identity. Partly inspired by William Hogarth’s A Rake's Progress (1732-33), the series comprises six tapestries that track the life story of Tim Rakewell from working class boy to death by Ferrari. Each tapestry is composed of characters, incidents and objects that Perry encountered while filming BAFTA award-winning series, All in the Best Possible Taste with Grayson Perry, for UK’s Channel 4: a programme that analysed the ideas of taste held by different social classes of the United Kingdom.

In this interview, which took place on the evening that Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art announced a major survey of the artist’s work, Perry discusses his tapestry works and touches on the upcoming Sydney show.

When did you first become interested in creating artworks using the medium of tapestry? Was there a particular moment?

I had always liked tapestry because I was always interested in fabrics and quilts and things like that. But I had never come across a way of doing it practically. I did try in the mid-nineties. I worked with an embroidery company, but they only created small embroideries, so I used to get someone to sew these bits into a large sewn patterned quilt, but it was a very time-consuming and unsatisfactory way of making a large fabric object.

But then I was working on a book at the time, and the print publisher guy one day came in and he knew this place that could convert my prints into a tapestry. When you make a tapestry it has to go through an awful lot of pre-preparation, but he put one of my prints through without much preparation, and it looked good. I kind of looked at it, and thought, 'Oh it has potential.' Then I drew up my first tapestry and I realised the scale it enabled me to work in. I was having a book launch at the time—and I thought let’s do something like a logo board, and so I did The Walthamstow Tapestry, which is 15 metres by 3 metres, and where we were going to do the book launch had a 20 metre wall, so we took advantage of it. From then on, I kept going. It is a technique that allows me to make small detailed works on a large scale—it works very well as a way of making a large object.

Why is the ability to work on a monumental scale so important to you?

Contemporary art real estate is growing. Galleries are so big now and so imposing and whenever I get shown where I am going to exhibit, I always feel a bit intimidated by it because I make small things that take a long time to make. I am always at a disadvantage to people who make huge things, and have large workshops and do videos and so on. So my tapestries are a way of me dealing with a very crafted and detail-rich object that also can be of a fairly large scale. So it was the answer to my prayers in a way.

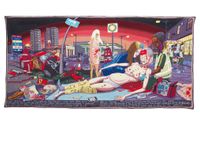

The Walthamstow Tapestry (2009), a monumental work, that traces the lifecycle of a man and woman, is heavily populated by logo names, many of which are associated with brands of mass production. Can we discuss why you referenced the brands as you have?

Every single item on the tapestry is a sort of logo. Every single item is named underneath by a brand. Brands are the modern myths and gods of our time. I thought about the tapestry and the large scale of them [tapestries], and thought of one of those religious fresco cycles, and I was also thinking about the most famous piece of textile art to British people, the Bayeux Tapestry, which tells the story of the invasion of Britain.

My tapestry tells the story of the invasion of marketing into our brain. You know, I didn’t really realise how it would work until I saw it up on the wall—I deliberately didn’t make any visual reference to the brands, I just sort of put the name there in a very nondescript text and the words themselves have this amazing effect. They create these sort-of ‘bombs of feeling’ that go off in your brain—they are so implanted, I suppose, as brands. As you scan the tapestry, you are taken through a sort of recent history in brands, and every one of them—for good or ill—has a sort of association. And it was a way of weaving literally and metaphorically a kind of emotion into the tapestry.

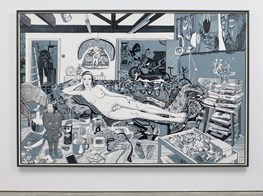

Exhibition view: Grayson Perry: The Walthamstow Tapestry, Victoria Miro, London (9 October–14 November 2009). Courtesy Victoria Miro.

The tapestry also references William Morris. Why did you want this reference to be incorporated too?

I called it The Walthamstow Tapestry because that is where my studio was at the time, in North East London, and I wanted to call it something after a place, to sort of echo the Bayeux Tapestry. William Morris was also brought up as a child in Walthamstow—just down the road from my studio—and of course he liked tapestry as well, and designed many tapestries, but his tapestries were hand-made. I liked the idea of doing something about brands in a medium that William Morris cherished as a type of bastion of down-to-earth craftsmanship. There is this sort of tension between the subject matter and the medium.

A version of The Walthamstow Tapestry has of course ended up in China. The China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, one of the country’s most prestigious art schools, bought a version of the tapestry.

Yes, The Walthamstow Tapestry is the first piece of art that I have sold to a collection in China, and I understand the first piece of foreign art acquired by the China Academy of Art too, so I am delighted about this. At 15 metres long, it is a very significant work to have in the collection.

It's a very 'British' work.

Yes, and I think that is a good thing. One thing I cannot bear and one expression that makes my heart sink is ‘global culture’. Because it is just a mush—it's the way teenagers dress the same in São Paulo as they do in the Philippines, as they do in Scandinavia and I find it very dispiriting. I always encourage students never to be afraid of being who they are, when they are and where they are—of being specific and local. None of the great artists in the past worried about being 'global'. Why should artists now? It’s bonkers. I like Chinese art because it is Chinese, not because it is a version of what I enjoy over in Britain.

In 2012, you created a series of six tapestries called The Vanity of Small Differences. I understand the work explores your fascination with taste, and it was made in conjunction with your filming of All in the Best Possible Taste with Grayson Perry. Why did you want to explore that idea of 'taste'?

I am one of those people always fascinated by what is in front of me. I am not one of those people who goes off to exotic locations to dance with nature. I am always interested in what is right in front of me, at my front door. And taste is one of those things that affects every decision we make everyday, but people aren’t exactly brought into awareness about it.

I have always been fascinated by class, and the main component of taste is class. Anyone who says there is no class system in society is lying because all societies have a status system of some sort or other. In Britain it is particularly pronounced and historically interesting, so it was a way of exploring a sort of nuanced status and unconsciousness. It is incredibly unconscious. When people say they like something, they never unpick the reason they might like something. People may think they are autonomous, but none of us is autonomous. We are completely conditioned by our upbringing and by our peers and by society and by advertising and so I was fascinated to unpick that.

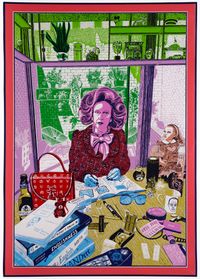

Exhibition view: Grayson Perry: The Vanity of Small Differences, Victoria Miro, London (7 June–11 August 2012). Courtesy Victoria Miro.

What did you find out about people that surprised you in undertaking the project?

I have a very good handle on the British class system. I think there are some poignant things—with the working class in particular. The working class system in Britain was shaped by the heavy industries, particularly in the North, which now don’t exist on the whole—it means that they have a type of ghost society. It takes generations to change. The emotional structures are there, but the industries are not. They have found other ways to replicate rituals, and play roles related to heavy industry—like men going to the gym: so instead of casting steel girders, they pump iron. They tend to spend a lot of money on their clothes and their appearance and their car, as opposed to a middle class person who might put more money into their house and their food as a way of showing their status. Each class has a different way of dealing with material culture that they use to show their place in society.

Art of course today is very much used as a sort of vehicle for upward mobility?

Yes, any other sort isn’t readily as available.

Class in Britain is pretty much stalled in a way. There are no more white-collar jobs—there isn’t an expanding white-collar sector for people to expand into. If you are going up, there is no way to go—it’s already full.

This year at Basel in Hong Kong, Victoria Miro will be showing Comfort Blanket (2014). I understand you wanted to name it 'Comfort Blanket' to reference a friend’s immigrant mother, who always thought of Britain as her security blanket. Why do you think that particular idea or story resonated with you?

I was already toying with the idea and it was sort of the perfect little story that went with it. I was thinking about drawing and trying to make a sort of quilt. My Grandmother got into the habit, during the war, of rescuing little scraps of wool and knitting them into little squares and sewing them into a blanket, and my other female relatives did the same thing. I saw the Queen as a grandmother figure, sort of knitting the blanket of the nation: collecting all the scraps that you could patch together to make the memory quilt or blanket of the nation. It also echoes a kind of giant bank note—a kind of token of Britishness.

You know we moan about Britain, but the reason people come here is because it is still a very safe place compared to a lot of places in the world—a very stable place. We shouldn’t moan about incremental changes to government because that is what keeps us stable. Revolution is inherently violent and chaotic.

Grayson Perry, Comfort Blanket (2014). Tapestry. 290 x 800 cm. Edition of 9 plus 3 APs. Courtesy Victoria Miro, London.

Comfort Blanket to me really stands out for its bold use of colour and pattern. How did you decide on the colours for this work? And the pattern?

I get seduced when I am working on Photoshop by the little colour options. When I start a tapestry I always think, 'Right this time, I am going to use muted tones, or even make it monochrome'—but then I get seduced. Also there is a kind of tendency in contemporary art [not to use a lot of colour] and the drive for 'tasteful objects'. When you walk around an art fair, a lot of the work is monochrome because it looks good in a modern interior—it looks ‘serious’. It is part of the seriousness of male interiors. Colour has this sort of association with frivolity.

I hear you are going to have a show at the MCA in Sydney—can you tell me about the show?

Yes. Well the thing is any big show of mine is going to be a survey show because I take so long to make work. I could only inhabit one room at the MCA, if I was to put my work from one year in there. So any big show is always going to involve a majority of works from the past. I am hoping it will be a good selection of work from right across my career involving all media: prints, sculpture, ceramics, tapestry and even a couple of video, film things that I did. —[O]