Lynda Benglis

Artist Lynda Benglis pictured with her work 'Scarab' 1990. Photo: Jonathan Pow/[email protected]

Artist Lynda Benglis pictured with her work 'Scarab' 1990. Photo: Jonathan Pow/[email protected]

In 1974, Lynda Benglis created one of the iconic works of recent art history, Centrefold. The work was presented as an advertisement in Artforum and featured the artist naked, save for a pair of sunglasses, her body oiled, her hip thrust forward, holding an enormous dildo.

Benglis has explained the work as 'a study of the objectification of the self', and it has been seen as an example of gender performativity, and as a cutting parody of the male dominated art world.

The work, which last November celebrated its 40th anniversary, is but one work of a career that spans over fifty years: a career characterised by a continuing investigation of material, media and cultural constructs to challenge the limits of painting, sculpture, eroticism, taste, feminism, and masculine hegemony.

The current exhibition at The Hepworth Wakefield Museum in Yorkshire, England is the largest ever museum survey of the Greek-American artist's work in the United Kingdom.

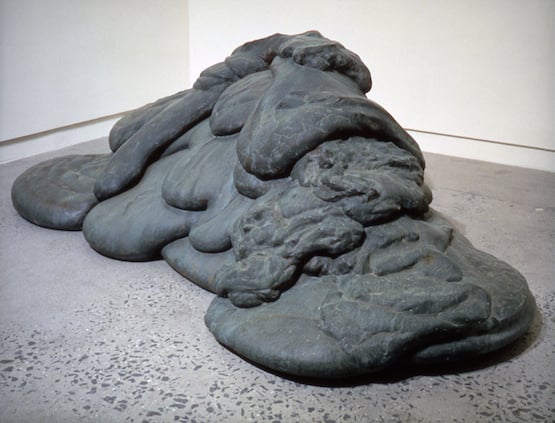

The show features approximately 50 works that span the entirety of Benglis' prolific career to date: from the early brightly coloured poured latex pieces that initially earned her critical attention to the glitter-encrusted 'knots' of the seventies. From her radical videos that explored power, gender relations and role-playing, to her more recent ceramic and polyurethane works.

In this interview, Lynda Benglis discusses the retrospective, the Whitney show she was forced to withdraw from and the final resolution on her first fountain work, The Wave of the World.

The whole idea of making a sculpture that has a presence and a form has always interested me.

ADA major survey of your work is opening at The Hepworth Wakefield in Yorkshire on 6 February. I am interested to hear whether staging a show in a museum space named after the artist Barbara Hepworth meant anything specifically to you?

LBShe is a very important artist, and she is a woman. So I am pleased to be showing there, but I know very little about her. When I am there, I plan to learn more about her.

ADThere is an interesting connection between her work and your own, insofar as some of her work was influenced by time she spent in Greece—she visited in 1954 following the death of her son and many of the works she created between 1954-1956 were inspired by her trip. You are of Greek descent, and I understand this has been very influential upon your own practice?

LBYes, my father was Greek, and my name—which I kept—is Greek. My yearly travels to Greece have been very important to my work. I often travelled with my grandmother to Greece: I spent 6 months there with her when I was eleven. My father was actually born in east Texas where they were discovering oil.

ADI understand your grandmother was very much a feminist icon for you?

LBYes. That is true. She was extremely significant. Her husband died very early—1955. I was the first female grandchild—which is very important in Greece, as the women inherit the property. She was my godmother, as well as my grandmother.

My grandmother travelled in her forties, and this was unusual and it impacted the way I was. It set a standard for me. My grandmother entered this country a few times before she stayed. She continued to travel back and forth after that. I went three times with her before I was thirty. I went back when I was 22 and then when I was 27. I went to fetch her in 1967 when she wasn't feeling well.

ADThe Hepworth show will include important examples of your poured works including Night Sherbet A (1968). Night Sherbet was created in 1968, against the background of certain social and political ruptures: Vietnam War protests, civil rights protests, Martin Luther King's assassination and then Robert Kennedy's too. Was this social and political context impactful? Please can we discuss the context of making the pour paintings?

LBThe social and political context of the time was very impactful. I can remember the march on Washington well. At the time I was doing a poured polyurethane work for Vera List—in her bathroom. She had a mansion on the Connecticut Sound. She had asked for a work, and I chose to do it in the bathroom.

The bathroom had beautiful white ceramic tiles running horizontally. I did a lipstick red corner work, and of course it was poured directly onto the floors and walls, and once done, it couldn't be removed.

After I had already started it, she came back from shopping and said: 'You better scrap it up dear. I don't like it'. I said: 'Well I am not going to do that.' So I finished it, and she ended up liking it. At the beginning she had said: 'Leave enough room for my husband to back up to the toilet'. Which I had done! She wanted me to do more: one on the stairs and one in a flowerbed.

ADDid you end up doing more?

LBI had never done one outside, and she wanted me to do one on the stairs. I think she liked the foam. But I didn't do it, because for me it was about the foam and its relationship to architecture, and about exploring the material as a formal statement in relationship to what painting had done—with regard to the stretcher and illusionistic idea of colour popping up from the floor.

ADYour exploration of 'illusion' was part of the issue with your floor piece being controversially ejected from the 1969 exhibition at the Whitney, Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials in 1969?

LBThat was really the first showing in New York of contemporary art that was all about process. I was the only woman asked to be in the show. [Robert] Ryman did a drawing on the wall. At the time he was doing canvases, sort of stuck to the wall. I said: 'Why don't you do it straight on the wall.' And he did.

I like the idea that you can create something that can look back at you and that does something that you can experience. I am trying to work with pieces that have a presence in sculpture that goes beyond the formal attitude.

[Richard] Serra was doing work in the corner. Barry Le Va was doing scattered pieces at the time. Sol LeWitt was doing paper drawings, only grids at the time, and small ones at that. He would wake up in the morning, paint all morning and then take calls at noon. And then Eva Hesse would call him up, and he would say: 'That was Eva Hesse. I don't have any calls before 12', but he invited me over before 12 to talk to him.

Anyway, it seemed to me it was time to do a coloured work that said something. But nobody else was involved with illusion.

Marcia [Tucker] decided she didn't want it in the show. But the funny thing is that the Whitney now owns it.

ADTell me about making the wax paintings, which I believe proceeded your polyurethane works?

LBI painted them with fire using a Bunsen burner and while I was doing this, I melted my wax and it created a marbleisation. I had created layers that were arm's length and brushstroke wide on a format that, when marbelised, didn't make sense any longer. I would use the Bunsen burner to melt the wax, and then I would allow the wax to freeze. There are only two paintings with marbleisation that are out there in the world; I think I destroyed the rest.

But then I decided that in fact I needed something to pour on the floor—the marbleisation didn't make any sense in terms of the format. I began using wax lanolin and bought large five gallons of latex natural rubber latex that had been packed in ammonia to preserve it. Latex was a mold material and I began to use this material. I found it by using the yellow pages and I bought it from a small company—anytime I wanted anything of a particular variation, I would just order it. I liked the consistency of the material.

The first rubber latex painting was done in 1968. I started working with the rubber latex paintings outside my studio in order to make large paintings. I began to do rubber latex and cantilevered polyurethane works in situ in various museums all over the US and Germany.

I showed my first, semi-flexible foam pieces with Galerie Hans Muller in Germany. Muller recognised my work early and brought that work to the Basel Art Fair, which was the first serious presentation of my work in Europe. Thereafter, Muller continued to recognise the fact and helped me produce a serious installation of the work, which Erich Hauser then thought was my mature work.

ADWhat materials are you today exploring?

LBI am involved with paper today. I am stretching large sheets of paper over a format of wire, to create different consistencies of forms. The whole idea of making a sculpture that has a presence and a form has always interested me. In some ways thinking about nature has always interested me. My use of fluid materials is in many ways related to gravity, and I have always been involved with skins too, sort of an exoskeleton.

Related to the idea of skin, is the idea of drawing form—this has interested me because my work is all about drawing, as well as volume, or lack of volume, or air. A lot of the forms I have done, are vessels that are containing something, or not containing something, and are living and breathing ...

It was natural for me to get involved with this type of questioning of materials and places.

ADOne of the materials you have worked with is water?

LBI have been working a lot with water. I am doing a lot of fountains now. I like the idea that you can create something that can look back at you and that does something that you can experience. I am trying to work with pieces that have a presence in sculpture that goes beyond the formal attitude. They look back at you. You can have abstraction look back you and you can feel something physically.

Brice Marden called his work a 'fact'. I agree with that. Art is a fact. The materialised form, in whatever material, is my statement.

I am usually involved in a kind of architecture that requires a floor or a wall. In contrast, if I do fountains, they can stand alone in nature. [Isamu] Noguchi said: 'Fountains are more than just water'. And I took that in. And when I was in Japan just after he died, I visited the place in which he worked on the island of Shikoku.

There on the island there were two Buddhist forms that he was said to have loved, stacked water-formed rocks, large natural boulders. They were said to be his favorite images and I understood why.

When I returned, I started doing clay forms, stacked. After that I combined both stacking and cantilevering in my work on the fountains. This is what I'm doing now with Crescendo and Bounty.

ADYour first fountain, has been the subject of recent controversy in relation to its ownership and damage to it, which you wanted to rectify?

LBThe first fountain that I ever did was for the World Fair during the early eighties. I conceived of The Wave of the World before I won the commission for the World Fair, and that is what I created. There were three winners that got backing: one from Mexico and a couple from France, Les Lalanne, who did animals together and then myself. So I did The Wave of the World and it was displayed in the Fair's main hall. I accompanied the sculpture to Monaco in 1991 and installed it before a casino there.

They wanted to buy it for the pond in front of their main square. However, it was not for sale because there were plans to install it in New Orleans. But it wasn't installed and it was damaged and for the past 20-30 years, I have been trying to get the sculpture back to fix it.

So this year, I finally got it back to Bob and Jeffrey Spring who own Modern Art Foundry in Queens and fixed it. I sent it back to New Orleans a week ago. The Helis Foundation is going to arrange for it to be installed in City Park in front of the New Orleans Museum of Art.

ADIn relation to other bronzes, I see the work Raptor, a bronze work from 1996 is included in the Hepworth show. It reminded me of Giacometti's, Woman With her Throat Cut.

LBThat is interesting. There isn't a connection, but it is always interesting to hear what people take from it. That work is influenced by Bernini. I love the Baroque, and the Hellenistic. Raptor has a rhythm to it, like a heart beat.

ADA lot of your work has a lyrical look to it.

LBI could have been easily a dancer. When I was very young I read about the famous ballerinas. I love the idea of movement.

ADThere are also some important video works in the Hepworth show, Female Sensibility from 1973, for example. You explored video very early on. Can you please tell me about what drew you to it as a medium?

LBI studied underground filmmaking and I began to think about the difference between video image and film time. I thought film was very interesting. Video was very interesting. I decided to do a media course.

At the beginning of the 1970s, I was invited to teach at Rochester University, where there were mainly scientists and I felt very happy there. I was interested in the idea of investigating moving image in real time, using different contexts. I even explored pornography—I said: 'Let's have animated pornography'. We had these moving video cameras and editing equipment.

I bought the first video animation, and you could play ping pong with a ball on this device (about $100), so that on the monitor you had this two way system, where you could play ping pong back and forth. This real-to-real thing really interested me. I bought speakers and all the equipment.

I remember Laurie Anderson came to see what I had, and I had the best monitor you could buy. Bob Morris was curious about what I had too. I was always kind of experimenting with things.

When I was a kid, my dad would buy me things because I was always curious about things, for example he bought me a projector with slides of different images from different places. It was natural for me to get involved with this type of questioning of materials and places.

Actually you know what, I have a feeling I met Barbara Hepworth while I was at Rochester. Could she possibly have been there?

ADI don't know—let me google it—well, looks like she has sculpture there, so perhaps you did.

LBYes, maybe I did meet her there. I have a feeling I did. —[O]