Rirkrit Tiravanija And Ryan Gander

STPI consistently delivers a challenging and exceptional exhibition programme. Resident artists — which in the past have included Ashley Bickerton, Eko Nugroho, and Do Ho Suh — are provided with an opportunity to use the Institute's outstanding print and paper-making facilities to create works which are then presented in the Institute's exhibitions.

At the time of this interview, incumbent resident Ryan Gander is enjoying his last day at STPI before he returns to his native United Kingdom, and previous resident Rirkrit Tiravanija has returned to STPI for the opening of his solo exhibition. The overlap presents an interesting conjuncture in which to consider how two conceptual artists might approach their time at STPI and in particular, the demands of presenting object based work.

Gander's works are still to be finalised, but a glimpse of their progress reveals a disparate, but intriguing selection — including a splattered plinth and its twin, prints of printing blocks tentatively entitled A World you Don't Want to Rattle, or We Go Dark For, and graphic extracts of police cars. Gander is known for his representation of everyday objects: what if a child's den-of-sheets were remade in memorialising marble (Tell My Mother not to Worry (ii), 2012); what if all the pieces in a chess set were remade in Zebra Wood (Bauhaus Revisited, 2003)?

He is also known for his language and performative works - for example Loose Associations Lecture (2002) consisted of a talk to slides that drew an intriguing line between seemingly disparate points on a cultural map - J.R.R. Tolkien to Inspector Morse to London's Barbican Centre.

Ultimately, Gander is a culture magpie exploring a rhizome of trajectories to up-end accepted notions. It is for this reason, one wonders whether the final exhibition of Gander's work will point less to a marked departure from his current practice, and more to a thoughtful and playful excavation of the medium of paper and print and what it means to be resident at STPI.

For Tiravanija, while the residency and the current exhibition do signify a significant departure from his usual practice, there are important threads that reflect a continuation of concerns that have always characterised his work. Like Gander, Tiravanija's work has steadfastly involved an analysis of the 'everyday', but he has more diligently pursued a performative approach to his practice — creating participatory events that investigate the nature of human interaction through constructed social environments. A pioneer of relational aesthetics, an early work like Untitled (Free) starting in 1992, converts museums and galleries worldwide into a kitchen where he serves rice and Thai curry to visitors, transforming these spaces into places of communion.

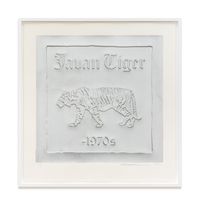

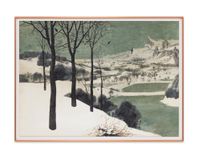

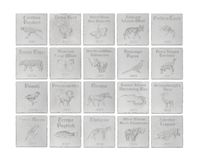

The current exhibition at STPI, Time Travelers Chronicle (Doubt): 2014 — 802,701 A.D, marks the first time Tiravanija has presented an exhibition consisting solely of object-based work, but nevertheless it still provides a framework for active audience participation. Inspired by H.G. Wells' dystopian novel Time Machine, the exhibition reconfigures the STPI gallery space into a time machine by a presentation of eight life-sized silver works on paper, paired with 3D printed objects on chromed pedestals, each representing a series of time portals. There is no communal curry on offer, but instead an invitation to mentally engage with the concept of time via an imaginative scenario of the artist's own making.

Can you remember the first artwork that initiated your journey with art?

Ryan Gander: I can, but it's terrible.

That's ok.

RG: Ok for you! Not sure it is ok for me?

Rirkrit is here now!

[Rirkrit Tiravanija joins the conversation]

Rirkrit, I was just asking Ryan if there was a first piece of art or an artist that initially inspired him to explore art. What about you?

Ryan Gander: We went for dinner last night for Chili Crab, and we were both asked why we became artists. I suppose this is the same.

Rirkrit Tiravanija: Yes, neither of us could answer that question.

Well instead - let's look at the connections between the work you have created while resident at STPI, and your earliest work. Rirkrit, are there any threads between your early work, for example a work like Untitled Free (1992), and the work you created during your residency at STPI?

RT: I guess that is the difficult part for me — having to work with the medium of print and paper. The fact is - I have not really worked before to create objects (as such). So in having to work with an object, I tried to come up with a narrative that I thought would actually get people more involved with what it is that I am thinking about in creating that object. The exhibition therefore is actually still kind of interactive. It is, in a way, a complete experiment to see how creating objects can still be interactive.

RG: The handprint work is very interactive.

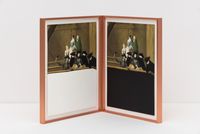

[Gander is referring to a work in Rirkrit's exhibition,The time travelers calendar B, negative present, where at a touch, traces of handprints are left behind to dissipate over time.]

RT: Yes, you have to put your hand on it for it to be activated.

But really it is pretty tenuous between what I used to do and what I am doing here. One element that carries through is perhaps this relationship between a work and the time you spend with it. Which is something I was interested in when doing Free Untitled (2005) and the other more performative work that I have done since. In my work, I have always tried to present a framework in which people have to be engaged. I think I pretty much am trying to make a type of frame where people will have to enter into the work itself. In this situation, I am trying to present a narrative to the audience that requires a type of mental engagement — an engagement via their imagination.

Rirkrit, you were involved with Il Tempo del Postino. The question originally posed by the curators was: 'What happens if having an exhibition is not a way to occupy space, but a way to occupy time?'. You explore 'time' in the exhibition at STPI. Are there any connections between Il Tempo del Postino and the question posed by that project, and what you have done here?

RT: Il Tempo Postino was trying to re-frame the position of the viewer in the sense that when I am working with the performative, people are working through the work or the space itself, whereas il Tempo del Postino was trying to move the work through the people in a kind of fixed frame — which was a kind of theatre space condition. I think in this work I want the audience to enter into a certain narrative structure that requires them to use their mind to jog through the space.

The whole thing about the work here is that it is supposed to be a kind of time machine.

RG: Sometimes it is easier to give the audience a framework or restriction.

Ryan, you also are a conceptual artist and have been put in a situation where you are asked to engage with the physical act of print and papermaking. How have you found the residency?

RG: Being here doesn't feel like you are being required to make prints. For me, it feels like I am here to make artwork about prints. From the outside you have the perception that people come here and they make prints, but actually it might be print or an object — it is just about the notion of printmaking.

How would the work you have made at STPI relate to an earlier work like Loose Association Lectures?

RG: There are lots of trajectories that you can take through them, but it would depend on who you were. You could take the geographical one of walking around the exhibition, or chronological one, or an aesthetic one. I mean, Loose Association methodology works with anything really.

I understand one aspect of the work you have created while at STPI also relates to the concept of time? I also wondered if history and different layers of history are relevant?

RG: History and time are relevant to everything. History is referenced in all of the works — they all reference bits of history — print history, history of this space, etc. But I think the works I have made here are a bit of a red herring because when you look at them, they all look different so it is hard to pull a thread through them. Essentially they all have something to do with blindness. I always knew I was colour blind - but when I got here I really realised I AM colour blind. Most of the work I make doesn't have any colour in it - colours are often irrelevant to the work. In thinking about the work I have been making at STPI, it all started with being blind and trying to nevertheless make a decision on a mark.

In relation to your work going forward, what do you think you will take away from this experience at STPI?

RG: I will take away a really nice print of two lobsters, which I am going to put in my kitchen [laughs].

Any residency is good, but this residency is particularly good because you are tested. There are these amazing Jedi print masters walking around who are waiting here to tell you what to do. It would be easy to waste the opportunity, so you have to think on your toes and be light footed and quick with your decisions. I wish I could work that fast all that time.

So it is a place that has challenged you and one you felt demanded a thoughtful response?

RG: Absolutely.

RT: On my part, I actually have never before sat in a studio and made work — so it was a bit like being in prison — but it was a good prison. I definitely think you have to think on your toes. But for me, working in a studio was a revelation.

It is exceptional to return now and see the works all complete and ready to be exhibited. When I left STPI, the prints were partially made — we were testing them — so we weren't really sure if they were going to work or not. So since I went away, the Jedi have actually made the works work. So it is quite an amazing thing to return and see the completed works. But it is a very different method of working for me. In a funny way it was an opportunity to step outside of my usual practice — like being on holiday, and I am trying to book myself back into this resort again [laughs].

You know the first question you asked — the one about the artists first memory of a relationship with a particular work — it's relevant here, because in creating the work here for STPI, I thought a lot about the artists who originally influenced me, and there are references to those artists that were, and still are, very important to me — like Duchamp, Beuys, and Broodthaers. When I was a student going through art history and at journalism school, it was seeing these artists that made me interested in art and made me want to be an artist. It was looking at Duchamp's urinal and Malevich's White on White that triggered my interest in art.

So the residency provided you with an opportunity to re-visit these early influences — to come full circle?

RT: Yes, it is interesting that I am actually referring to those things that originally inspired me to investigate art, now that I am being forced to actually create art objects.

Let's discuss the work that appears in the Second Chapter of the STPI exhibition, Be sure to pack the toothbrush, eat Curry noodles through the wormhole?

RT: I wanted to achieve a type of passage through time using the prints. It all started from looking at Darwin's diagram for the 'Tree of Life'. It came up as I was leafing through some material when thinking about ideas for the work. Through the 'Tree of Life', I started to make this plot of a type of Time Machine - when you enter one end in a certain time and come out in another. Looking at Darwin's sketches of his diagram - it sort of explodes into a kind of time warp of information. I made a work for my exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in London, which was kind of a retrospective work — a work really about looking back. I wasn't very comfortable about putting my old works back together, so I wrote a small science fiction time travel story about people going back in time to look to find me because I had done some bad work, and they wanted to go back in time to stop me making the work. In typical science fiction stories regarding time travel, there is always something you have to stop before the future happens. When I was in London I used to go to ... Ryan, what is that patisserie place called again?

RG: Patisserie Valerie.

RT: Yes, to Patisserie Valerie, and in my story, and in order to stop me making the bad works, the protagonists go to Patisserie Valerie and after eating a bowl of curry they are transported in time back to Untitled Free (1993) — so this kind of structure came into play with this idea of the 'passage of time'. So I was pulling into play different kinds of possible scenarios about space and time. I want the viewer to imagine they are going through this space that actually is about moving through time.

RG: Rirkrit, if you could time travel where would you go?

RT: Well probably back to the Chili Crab, back to the last good meal [laughs].

Where would you travel back to Ryan?

RG: Well actually I have also just made a work about time travel. I made it this week at STPI. It's a real subject. Mine is called There are People Having More Fun with Prostitutes or Toki No Nagare, 2014 (Passage of Time). Louis Vuitton, [Mointe] and Goyard — they are luxury brands from the same street in Paris and they were all created around the same time, but they went on different trajectories and ultimately they are all now in competition with each other. So I thought about re-visiting history and I re-imagined them actually on conception all coming together and forming one company. So the work I have created takes the form of an art student's portfolio and printed on the folio is a re-designed pattern reflecting the amalgamated brands. And this is left by the door at STPI and addressed to Emi the Director of STPI, so it looks like it is somebody's cheap portfolio that has been delivered. But it also has a monogram painted on it, 'SS', which stands for Santo Stern - an artist whom I sometimes make work by — a fictional artist.

Why did you create Santo Stern?

RG: I invented Santo because I saw how easy it was to make really bad art and I needed a vessel from which to release my own bad art — so I make work by Santo that is really horrible and I really enjoy doing it. If you can imagine the most disgusting artist that you could ever meet — morally, ethically and aesthetically — he is an arrogant guy and pig-headed and his work really grates. There is a work here by him.

Tell me about the work tentatively titled, Nothing is without Meaning?

RG: When I got here there were lots of plinths — they were dirty and so I reproduced what is essentially a dirty plinth. So, when you enter the gallery you see something that looks like it belongs in the workshop and which appears to have been accidently left in the gallery space. However, I made it as a twin, because I wanted the viewer to be aware that the work is where it should be — it's not a real plinth, but in fact a work about mark making.

RT: So it is essentially a double print?

RG: Yes, it is a three-dimensional double print. But it is also two fake dirty plinths.

What about the titles you give your work - do the titles come before you make the work, or after?

RG: I made 11 works while at STPI — for two of them I thought of the titles while I was here and for the others....well I have a list of titles on my phone [holds his phone up and scrolls through titles], and I write titles when I think of them on this list, and then I just pick one.

Are you serious. Give me a title now?

RG: "Whispering Vagina" or "Dreamcoats".

What about you Rirkrit - what about the titles for the works you have created for the exhibition at STPI?

RT: I made them as I went along. Sometimes something comes up and I just jot it down. Usually I don't even title my work. But for this show, the titles — well they are more like sub-titles — something that is a portion of the larger thing.

RG: Do you ever title works to make them more complicated, or to divert the spectator? So they settle on different paths?

RT: In some ways — in this particular exhibition, it is about pointing the audience to things they should be thinking about. I am not very keen on making images, so the imagery is almost made via the narrative structure - that is the platform — created in many ways via a sub-title (which is the title of a work).—[O]