Taryn Simon

In 1936, an American ornithologist named James Bond published the definitive taxonomy Birds of the West Indies

. Ian Fleming, an active bird-watcher living in Jamaica, appropriated the name for his novel’s lead character. He found it “flat and colourless,” a fitting choice for a character intended to be “anonymous. . . a blunt instrument in the hands of the government.” This co-opting of a name was the first in a series of substitutions and replacements that would become central to the construction of the Bond narrative.

Taryn Simon's Birds of the West Indies takes the name and format of the original Bond’s taxonomy to present an inventory of women, weapons, and vehicles—recurring elements in the James Bond films between 1962 and 2012. This visual database of interchangeable variables used in the production of fantasy examines the economic and emotional value generated by their repetition. It also underlines how they function as essential accessories to the myth of the seductive, powerful, and invincible Western male.

Maintaining the illusion upon which the Bond narrative relies––an ageless hero with an inexhaustible supply of state-of-the-art weaponry, luxury vehicles, and desirable women—requires a constant process of replacement. A contract exists between the Bond franchise and the viewer that binds both to a set of expectations. In servicing the desires of the consumer, fantasy becomes formula, and repetition is required; viewers demand something new, but only if it remains essentially the same.

Ten of the fifty-seven women Simon approached to be part of Birds of the West Indies declined to participate. Their reasons included pregnancy, not wanting to distort the memory of their fictional character, and avoiding any further association with the Bond formula. Simon represents each missing woman by reinserting the black rectangle cut from the mat to frame their would-be portrait, covering and at the same time representing their absence.

Simon’s film Honey Ryder (Nikki van der Zyl), 1962 documents the most prolific agent of substitution in the Bond franchise. From 1962 to 1979, Nikki van der Zyl, an unseen and uncredited performer, provided voice dubs for over a dozen major and minor characters throughout nine Bond films. Invisible until now, van der Zyl further underscores the interplay of substitution and repetition in the preservation of myth and the construction of fantasy.

The sequencing of women, weapons, and vehicles in Birds of the West Indies was determined using a random number generator called the Mersenne Twister, used for statistical simulations and in computer programming languages. By randomly reconfiguring the ordering of the works, Birds of the West Indies continuously mimics a longing for endless reiteration unaffected by time and history.

How would you describe your work, since it’s clearly not just photography?

I look at my work as interdisciplinary—not existing in any specific envelope. These days most are working in interdisciplinary forms where things are less easily defined or clear. I find titles limiting and a means of control.

I’m interested in spaces of confusion and disorientation in which subjects and thoughts mutate and transform—and are difficult to understand, and even more difficult to picture. I try to look at those amorphous spaces through something actual—looking at abstraction through something understandable as opposed to through abstraction itself. I’m interested in the questions that keep you up at night – what we are doing here, if there’s purpose—but driving at the unanswerable through something that appears tangible.

Why are photography and text both so integral to your work?

I use photography and writing to highlight an invisible space between the two – a space governed by interpretation, translation and manipulation. These two poles are constantly fighting each other and supporting each other and sometimes doing both at the same time. I do find myself more interested in the camera as a machine, allowing me to inventory certain subjects that are then made into works through their relationship to text, space, font and graphic design.

You were studying science before entering into art. Does that indicate something about your interests?

I am often skating a line between science and aesthetics. Science itself gives the appearance of authority or a clear answer. Graphic design plays a big role in rendering this sense of certainty to the public. I like toying with that relationship (between answers and data and the way in which they are conveyed), and creating systems that appear absolute, but are in fact just personal creations.

Both my father and grandfather were obsessed data collectors and photographers. I was introduced to the larger world, the construction of facts and fantasy, and photographic production through their frequent slideshows. My father recorded histories, peoples and landscapes in Afghanistan, Iran, Russia, Thailand, and Pakistan… And brought me the visual evidence coupled with his other-worldly narratives. My grandfather’s perspective was the opposite—a macro view of the stars, nebulas, insects, minerals and plants. He spent years grinding glass to perfect a lens for his telescope. Both had closets stacked with slides. And both identified every photograph with a considerable amount of collected information.

Taryn Simon, Shark Brain Control Device, 1983. From the series Birds of the West Indies, 2013. Framed archival inkjet print and text. 15 11⁄16 x 10 7⁄16 inches, (39.8 x 26.5 cm). Image courtesy Gagosian Gallery

How do you select the subjects or themes of your works?

The works are often guided by things I've been introduced to in the previous project—peripherally or directly. Or they are a rejection or move against previous work. They start simply, and then unfold into complicated programs. I read a lot – and often cull ideas from discoveries in both fact and fiction.

For example, in A Living Man Declared Dead and other chapters, I tried to articulate certain systems, patterns, and codes through design and narrative. I travelled around the world researching and recording eighteen bloodlines and their related stories. I was exploring the unanswerable questions regarding fate and its relationship to chance, blood and circumstance. Its failures and rejections became a big part of the work. There are several empty portraits representing living members of a bloodline who could not be photographed for reasons including dengue fever, imprisonment, army service, and religious and cultural restrictions on gender. Some just refused because they didn’t want to be part of the narrative. In the end, the blanks establish a code of absence and presence. The stories themselves function as archetypal episodes from the past that are occurring now and will happen again. I was thinking about evolution and if we are in fact unfolding, or if we’re more like a skipping record—ghosts of the past and the future.

For A Living Man…, you traveled to 18 countries over a four year period of time. Has your gender ever been a challenge in this context?

Being a woman has been very difficult at times, and in others helpful. There were a number of difficulties to avoid along the way, something always happened: flash floods, typhoons, landslides, carjacking’s, authorities who didn’t want me photographing certain subjects. We traveled with a ton of gear to accommodate our moving studio which made us uncomfortably visible and indiscreet. In Tanzania for example, our equipment was seized by corrupt authorities that demanded 80,000 dollars for its return. I was there to photograph the bloodline of the director of the Tanzania Albino Society. Albinos in Tanzania are hunted by human poachers who trade their skin, limbs and organs for large sums of money to witchdoctors who promote the belief that albinos have magical powers. This is a subject the authorities are not keen to publicize.

Your work seems very brave. Are you?

It’s quite the opposite. I’m in fact very fearful and many of the projects are about confronting those intimidating and haunting lines.

What are you up to now?

I just completed a project for the Venice Biennale on the paperwork of power and the ways in which human kind exerts the illusion of control over events and the natural world. I'm currently working on a film project in Russia and a large scale performance piece for the Park Avenue Armory in New York and ArtAngel in London. —[O]

Birds of the West Indies / A Short Interview for Photo Shanghai

How did you begin your research for Birds of the West Indies? Did you watch all the James Bond films?

The films were watched chronologically in a binge. And then reviewed again and again. The entire studio was involved.

Taryn Simon, 1969 Mercury Cougar XR7, 1969. From the series Birds of the West Indies, 2013. Framed archival inkjet print and text. 15 11⁄16 x 10 7⁄16 inches, (39.8 x 26.5 cm). Image courtesy Gagosian Gallery

Did your understanding of the Bond franchise change after watching and re-watching all the films for this project?

The films journey through economics, race, gender politics, weapons development and proliferation, branding, identity, global politics, aesthetics in such a radical form. They truly stand as a powerful record of culture's role in all of these categories. Interestingly I was told that MI6 at one point looked to Bond for weapons development ideas as opposed to the other way around. Perhaps that's the way it goes: imagination and fantasy first.

Will you be in the movie theater for the next James Bond film?

Front and center.

How were you able to photograph the elements of the James Bond film franchise? What was the hardest thing to find?

The weapons and vehicles came from different sites throughout Europe and America: the official Bond archive, auction houses, private collectors, museums. The earlier items presented more obstacles because the value of the franchise was not yet established and elements of the films weren't preserved as they are today. I'm always interested in archives that develop before value is established - and then how they mutate once it is recognized -- the collision of low and high art.

Did any one of the interchangeable elements of the Bond franchise have particular meaning for you?

As a metaphor, I always liked the Hasselblad signature gun in which a camera is a weapon of death.

Were you concerned about the project’s viability when some of the actresses refused to be photographed? What made you decide to indicate these actresses’ absences with “blank” images?

When Ursula Andress declined to participate, I was sure the project was in jeopardy of failure. She is THE bond girl. I became obsessed with getting her image and history, and in that process discovered that the voice of her character in Dr. No is dubbed by an uncredited English woman named Nikki Van der Zyl. Ursula's character, Honey Ryder, is a fragmented creation; pieced together to compel. In the end Ursula's absence was a blessing. I created a film in which Nikki, who had always been invisible in the Bond universe, reads the complete lines of Ursula's character - and becomes visible.

Nikki was the most prolific agent of substitution in the Bond franchise. From 1962 to 1979, she provided voice dubs for over a dozen major and minor characters throughout nine Bond films. For me, she underscores the interplay of substitution and repetition in the preservation of myth and the construction of fantasy.

The empty portraits disrupt the archive and present obstacles I couldn't transcend. In my work, I'm often associated with access to difficult and complex areas and subjects. I assumed this project would be a break from those difficulties. Surprisingly, it was even more difficult. Ten of the fifty-seven women I approached to be part of Birds of the West Indies declined to participate. Their reasons included pregnancy, not wanting to distort the memory of their fictional character, and avoiding any further association with the Bond formula.

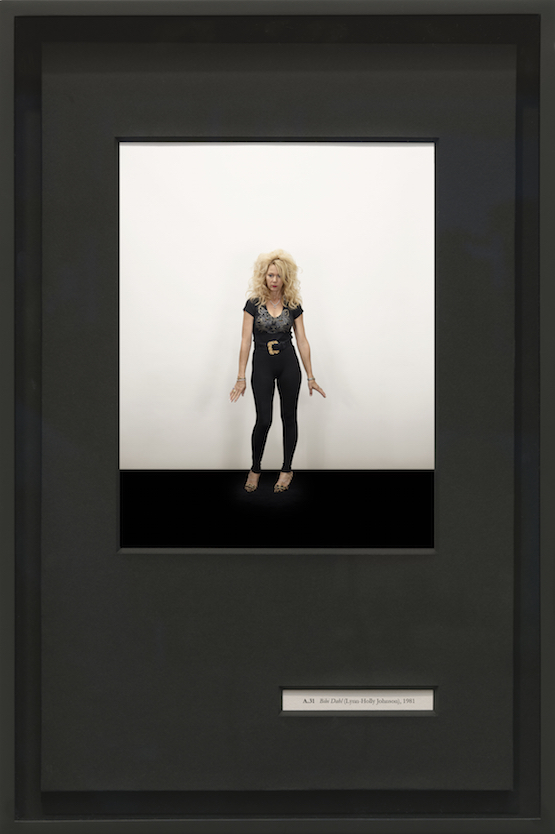

Taryn Simon, Bibi Dahl (Lynn-Holly Johnson), 1981. From the series Birds of the West Indies, 2013. Framed archival inkjet print and text. 15 11⁄16 x 10 7⁄16 inches, (39.8 x 26.5 cm). Image courtesy Gagosian Gallery

How do you view the portraits of the women in relation to your ongoing exploration of reality of fiction in the history of your work?

I see the women's portraits existing in this strange liminal space between reality and fiction. Or a space where both reality and fiction disappear and a third space opens up that is neither. The mark of a bond girl is so indelible; there is often no room for another reality or identity. Their poses and clothing play a part in that push/pull. —[O]

Interview supplied by Photo Shanghai