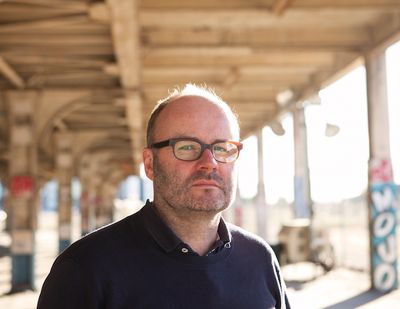

Thomas Demand

Thomas Demand. Photo: S2S.

Thomas Demand. Photo: S2S.

For two decades German-born artist Thomas Demand has captivated collectors and museums alike with his boundary pushing photography. With the dedication and single mindedness of an obsessive compulsive, Demand recreates meticulous and detailed life-size paper models of scenarios gleaned from media images, and then photographs them, blurring the lines between the real and the artificial with his sculpture-photography hybrids.

On the surface the scenes appear banal, but are often laden with historical or cultural significance, such as the assassination attempt on Adolf Hilter, or the studio of the Baader Meinhof gang. After photographing the model, he destroys it, leaving only a photographic print: a photo of a model based on a photo. The photographs can appear lifeless, cold, and sterile on first encounter, but the devil is in the detail of Demand's work.

These simulacra images often represent the still quiet moments after the passing of dramatic events; Whitney Houston's last meal in her hotel room before her death; the Paris tunnel where Princess Diana died in a car crash. They are not faithful recreations of the sourced media image; sometimes objects are changed and details are diluted in the model, or the artist's hand is revealed, drawing our attention to the artifice of the recreation. But the works also play with ideas of memory, our reconstruction of an event or image, and how we understand it. The photographs lack any text explaining or contextualising the image, encouraging the viewer to bring their own subjectivity to the narrative.

Having studied sculpture at Dusseldorf's Kunstakademie, alongside renowned artists Katharina Fritsch and Thomas Schütte, Demand began his career as a sculptor, producing paper models. In the early '90s he shifted his focus to photographing purpose-made paper sculptures. His work has since earned him international recognition and a mid-career retrospective at MoMA in 2005, as well as major solo shows at London's Serpentine Gallery and the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin.

DAHow would you describe what you do in your work?

TDI'm combining a painter's and sculptor's concerns in a third medium, photography. It's a reflection upon the media sphere of images surrounding us.

DAYou initially started out as a sculptor producing paper models, and then later shifted to photographing models. What prompted this shift?

TDIt has been a gradual progress. In the beginning I used to make very small sculptures and then throw them away, because I lived in a very small apartment and didn't know where to put them. So I would look at them and think that if I needed to I'd always be able to make them again. Then a teacher told me I should record them, to see if I was getting anywhere. And so I started to photograph them. But the pictures were terrible, because I didn't know how to take photographs. That was my first problem.

One day I saw a pair of photographs and thought that they worked really well together. And I asked myself: what should I do now? I learned how to take photographs. And then I thought: what happens if I take a photo of a photo, if I use as a source something that is not an object, if instead of using my own experience I use somebody else's? So I photographed a place that I remembered very well because I'd seen it many times in books. Many of my photos are pieces of paper that show another piece of paper, which in fact it is not.

The reason is that the majority of stories that catch our imagination are of this kind: the photos in newspapers are almost always connected with violent events. What interests me is getting to the root of what happened, imagining being the person who was there at that moment and trying to reconstruct the facts in an objective way.

DAThe story behind some of the scenes that you reconstruct and photograph are often quite dramatic: the scene of the assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler; the studio of an artist targeted by the Baader-Meinhof. Often the scenes themselves are quite unremarkable and mundane, while others are like crime scenes depicting the quiet aftermath of violence or trauma. Why do you choose to depict these in your work?

TDThe reason is that the majority of stories that catch our imagination are of this kind: the photos in newspapers are almost always connected with violent events. What interests me is getting to the root of what happened, imagining being the person who was there at that moment and trying to reconstruct the facts in an objective way. Take Saddam Hussein's kitchen for example: at the time Saddam was painted as the most evil person in the world (and maybe he was, I don't know). The photo of Saddam Hussein's kitchen was taken by the soldiers who found him, and if you look at it all you see is a kitchen, with the same Tupperware as I have at home.

So you say to yourself: this is the devil? The most wicked person in the world cooks eggs in the same frying pan that I use? All this has an extraordinary power: you say to yourself, is it possible for this long story to end simply with this image?

DAHow do you source the original imagery that you base your work on?

TDWhat I need is a picture that is remarkable even without the story behind it.

DAYour reconstructed scenes aren't faithful depictions of the original photographs they're based on. Objects are altered, sometimes they're missing in the reconstruction, or the artifice of an object is evident, making us aware that we are looking at a simulacrum fashioned by the imagination and by the hand. What are you trying to convey through this?

TDI leave lots of important things out and at the same time I am leaving out traces of names and letters on paper and things that got used up. All kinds of details that I leave out to keep that fragile balance open to keep the game open in a sense so it's a proposition, it's not fact. I'm just trying to keep that process visible to show that this is a reconstruction instead of the real things and that's why I would be reluctant to call myself a journalist as well because I'm actually not adding any truth to anything.

I think things are not at their most beautiful when they are complete.

If anything it's about truthfulness, like in a novel if someone writes about their childhood in Russia, you would never say it's not true, but you may say he might have forged some facts and it is a really impressive description of it. With a fictional writer you would never be able to really say, "this is not true," you would only be able to say, "I don't like the novel," or "he really bent reality," or something like that. That's all qualities in fictional writing and not advantages or disadvantages.

Whereas, when a journalist starts doing that, he's out of business, so I'm on the border where real things become fictional. The other thing is that leaving out a lot of details has to do with perfection verses beauty. I think things are not at their most beautiful when they are complete. A sense of perfection comes when things are not flawless. Perfection is not about having no mistakes, perfection is when you know you can leave things open for imagination and you can also leave them open in a fragile state.

You don't have to define everything. Think of the most beautiful novels where the imagination of the reader is triggered and you can imagine and feel things, but that doesn't happen when every little thing is written out. That is why I try to do my work myself and decide with every object: how much information do I need and how much is too much?

DAWhat role does memory play in the reproduction of a scene?Memory is amazing. We talk about pictures in our head, but of course no one has a picture in their head, we are constantly reconstructing things. Photography and memory have a weird love-hate relationship because on one hand if you have a photograph of something you aren't going to remember it so well. On the other hand, you might remember things because you only have a photograph.

TDSo there are many people that would say don't make a photograph all the time because you won't remember the moment, you will only read the moment as something you can tweet about later or you only read the moment as something which makes a nice photograph and the photograph somehow replaces the experience. On the other hand the photograph reminds you of so many things in your life that you have forgotten already.

The other thing is when you remember something your brain starts to construct and put together all the things you need to imagine that picture. So whenever we talk about pictures or we remember pictures or an incident, which might have a picture attached to it, you construct it. It's not that you have it already. So during reconstruction, you change it a little. If you tell a story four times it will be a different story the fourth time. Essentially the facts will be the same but you can make it shorter, or longer.

I want to make sure that people look at the images using their own associations. I don't want to offer a canonical and defined commentary because there is no such thing.

DAWhy did you first start reconstructing scenes to photograph in paper and cardboard? And what is the meaning behind your destruction of them afterwards?

TDMore than anything else I realised one day that photography was not mere documentation. At that point the process was more important than the object I was photographing.

They don't last anyway; most of them are made of paper and cardboard and they simply fall apart. I don't want to have to fix it all the time in a museum. Also, I always want to do things I can get rid of. I move around a lot and I don't want to have too many things. A room full of stuff drives me crazy.

DAYou don't really offer explanatory text or context for your images. Why?

TDI want to make sure that people look at the images using their own associations. I don't want to offer a canonical and defined commentary because there is no such thing.

DAYou have relocated from Berlin to Los Angeles last year. Has that influenced what you want to depict?

TDAt the moment, LA feels more inspiring. I lived in Berlin for 14 years—the longest I've lived in any one place—but by the end, I felt I needed some fresh air. LA feels freer. —[O]