All the World's Futures: the 56th Venice Biennale

How do you take in all the world's futures during the opening days of the Venice Biennale, a world unto itself that is staged in a city that feels like an alternate universe?

Such were the questions surrounding Okwui Enwezor's 56th Venice Biennale, All the World's Futures: a presentation of 89 national pavilions, 44 collateral events, 136 artists from 53 countries in the central show (at the Giardini and Arsenale), and a host of satellite (and some rogue) projects. "It's too big!" and "There's too much!" were the buzz phrases punctuating rushed encounters by those navigating a fragmented exhibition staged on a sinking archipelago without cars. It's true. Our world is big, and it's filled with interlocking histories that define and divide us, too.

And so, Enwezor takes this dissonant vastness and inserts it into the Venice Biennale's problematic world space: an exhibition that takes a relic belonging to a worldview that grew out of the age of Western imperialism and nationalism. Many have called the national pavilion model archaic for a 21st century context, a time when the nation state is being unraveled and renegotiated. It is an exhibitionary form Ivan Grubanov deconstructs in United Dead Nations: an installation for the Serbian Pavilion that includes the flags of nations that have ceased to exist since the Venice Biennale's inception in 1895, from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, to Yugoslavia. In this, Grubanov offers a consideration of what it means to be a nation in a post-global age: a question that seems to have fed into a number of the pavilions.

The Ukraine Pavilion, Hope!, for example, takes the form of a large glass cube positioned in what must be the most visible crossing point of the Biennale, located outside the grounds of the Giardini. It is a transparent act of defiance contrasted by Irina Nakhova's restoration of the Russian Pavilion's façade to the original 1914 deep green: a coded statement suggestive of a return to imperialism (and where Ukrainian artists later staged an elegant mock occupation). Meanwhile, Christoph Buchel's conversion of an old Catholic church into a Muslim community centre (produced for the Iceland Pavilion and intended for Venice's sizeable Muslim population) crept in like a Trojan horse. Provocatively titled THE MOSQUE, it was deemed a security threat by Venetian authorities almost immediately after it opened.

The oldest foreign pavilion, Belgium, presents Personne Et Les Autres: Vincent Meesen & Guests, an excellent group show (and undoubtedly one of the Biennale's best pavilions) curated by Katerina Gregos. The exhibition takes as its starting point the date of the Belgium Pavilion's inauguration in 1907 during King Leopold II's reign, and one year before Congo Free State became Belgian Congo. It then expands with works that offer political, historical and cultural crosshatchings arising from the inter-relations betwee Africa and Europe by Sammy Baloji, James Beckett, Elisabetta Benassi, Patrick Bernier & Olive Martin, Tamar Guimaraes & Kasper Akhoj, Maryam Jafri, Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc, and Adam Pendleton.

These surround Meesen's three-channel video installation One. Two. Three (2015), which revives the unpublished lyrics of a protest song written by a Congolese member of the Situationist International, Joseph M'Belolo Ya M'Piku, in May 1968. From 1907 to now, Messen's work expands a history of a coalition of artists, philosophers and revolutionaries formed in 1957, and whose founding is associated with the First World Congress of Free Artists held in 1956 in Alba, Italy. (The final Situationist International conference took place in Venice in 1969 and it officially dissolved in 1972.)

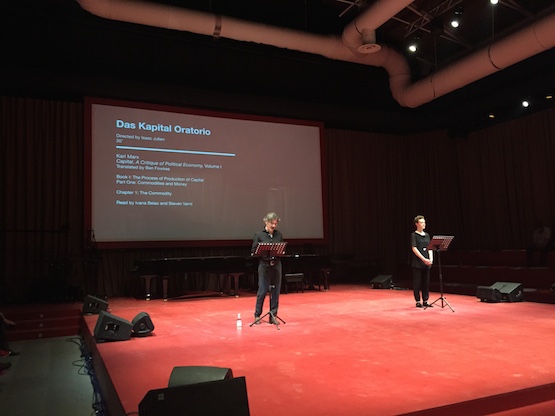

In Personnes et les Autres, racial divides are transcended through a common, historical struggle. One that brings to mind Lenin's assertion that imperialism is the highest form of capitalism: a point also made in Enwezor's rigorous, almost too-tight exhibition. At the Giardini's main show, for instance, classical Marxism abounds. Central to this is "Das Kapital Oratorio": a reading of Marx's Kapital that will take place throughout the course of the exhibition. The performance is supplemented in the main show by KAPITAL (2013): the recording of a conversation between Isaac Julien and radical geographer David Harvey at the Hayward Gallery.

The discussion is expanded on considerably in Alexander Kluge's three-channel installation Nachrichten aus der Ideologischen Antike: Marx, Eisenstein—Das Kapital [News from Ideological Antiquity: Marx, Eisenstein—Capital] (2008—2015), a condensed version of a 9-hour documentary. As Tom Roehrig writes, it invokes Frederic Jameson's assertion that Marx is neither actual nor outmoded, but classical.

Not everyone appreciated the Giardini exhibition. A few days after the opening a photocopied image depicting Enwezor standing with Marx was stuck on a lamppost at the entrance to the Giardini. On the picture was a question: WHAT DOES AN ELITIST EVENT LIKE THE VENICE BIENNALE HAS [sic] TO DO WITH KARL MARX?

In short: everything. Marx and Engels called London's 1851 Great Exhibition of Works and Industry (which shares a genealogy with the Venice Biennale): "striking proof of the concentrated power with which modern, large-scale industry is everywhere demolishing national barriers and increasingly blurring local peculiarities of production, society and national character among all peoples."

On the 2015 Venice Biennale, JJ Charlesworth took the same line, asking: "Could it be that in ... all the talk of politics and capitalism, the real point for all these countries and non-countries is to be part of the new machinery of the global economic world order, of which art biennials have become the cultural window-dressing?"

But Enwezor did not adhere to a uniform worldview. Out of the 136 artists taking place in the central show, 89 are showing at Venice for the first time. Densely hung like a cluttered art fair, this was not an easy exhibition to take in. On first walk through, the Giardini show really did feel like a case of Capitalism eating its own tail: Marx has become the elephant made visible in the room. Yet, the works are neat; the names are well known. The encounter with Gursky was an unsurprising surprise. It all feels too institutional, somehow, even in its critique.

There is a sense that Enwezor knew what he was doing, though. Take the choice of Gursky, an artist who suffered the fate of many who became market darlings when he sold_Rhine II_ in 2011 for $4.3 million at auction. There was an immediate backlash not only in response to the value of Gursky's work, but to its ubiquity, something that has happened to Oscar Murillo, an artist who has been the focus of much critical contempt due to the speed of his emergence and his market rise, particularly since A Mercantile Novel at David Zwirner in 2014. Murillo has been critiqued for referring to his own life experience in his work, even if it is used to consider economies of production and exchange. This is how it goes, it seems—the market not only absorbs its discontents, it dismisses them, too, which only serves to stunt a conversation before it has even started.

Thus, if there is anything this Venice Biennale seeks to address, it is our capacity as observers to read a serious visual statement made in the most ridiculous of spectacles. After all, in what a collector recently called the world's greatest art fair, there must be some irony to the Biennale's title. In the marketplace, futures are exchanges related to derivatives—the financial instruments that instigated the crash of 2008.

That some critics found this all hard to take was as revealing as the Biennale itself. artnet called this the worse Biennale in living memory, calling Enwezor an "angry" curator who curated a "violent" show. But colonial history was—and is—violent, even when the violence has become a historical memory, or has manifested as infrastructural form. In this sense, it seems Enwezor, in what he has called his last undertaking of this kind, is not only asserting once and for all that the world is round and multi-coloured, but that it is also tethered to historical struggles associated with the homogenizing (and often aggressive) forces of modernity.

This brings us to the Arsenale, where capitalism is expressed as a systemically global—or globalising—condition. Mika Rottenberg's witty NoNoseKnows (2015) is a precise addition to an ongoing series of video works that explore systems of labour and production through various chain reactions set up in tightly composed settings so as to express what Roberta Smith called "the collapsed distance of globalism"—a system bound up in the legacies of imperialism and colonialism.

Taryn Simon presents Paperwork,and the Will of Capital, An Account of Flora as a Witness: a series of texts each paired with an image of fauna and a dried specimen that present "agreements, contracts, treaties, and decrees drafted to influence systems of governance and economics," including one between China and Pakistan to enhance satellite navigation systems. (And which recalls Simon Denny's conflation of the NSA with contemporary air travel and old imperialist structures for the New Zealand Pavilion.)

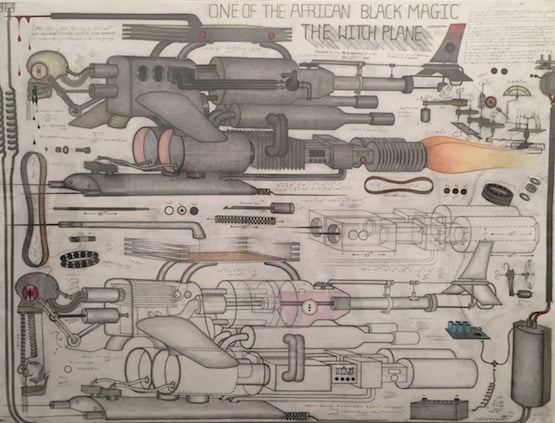

The world in Okwui Enwezor's frame is both abhorrent and hopeful. Abu Bakarr Mansaray's drawings from 1997, for example, were produced as a response to his experience of civil war in Sierra Leone, one year before he fled to Europe. The works appear like annotated designs for fantastical weapons—the kind made by children escaping into their own fantasy: that place we all go when we hope for something better.

In Oscar Murillo's ongoing project, Frequencies (an archive, yet possibilities) (2013-), tables are covered with neat piles of canvas that have been attached to school tables and covered in doodles by students from all over the world over a period of time, then sent back to the artist to sort. Part of the work is the presence of attendants waiting to explain the pile of drawings to visitors for the duration of the Biennale. This is a typical Murillo move if you think about it. Staged in such a way that recalls an appraisal, it subverts the question of value within a heavily marketed space by activating art's social worth by offering a glimpse into nascent minds.

This imaginative potential is grounded in practical (and political) form through an installation by Gulf Labor, a coalition of artists protesting the exploitation of migrant labourers building cultural institutions (namely, the Guggenheim) on Saadiyat Island, UAE. Sonia Boyce's_Exquisite Cacophony_ (2015) takes a different route to communicate a similar message to Gulf Labor's local/global concerns.

In the video, Elaine Mitchener and Astronautalis improvise in a performance constructed by Boyce, who intervenes at the end of a long dialogue between the performers by asking them and everyone else in the room to scream their name for ten seconds. This crescendo ends in laughter and hugging: a view of the collective as a sum of choral differences that re-claims composed dissonance for the purposes of emancipatory potential.

In this sense, All the World's Futures is about perspective more than anything. In Filip Marciewicz's Paradiso Lussemburgo (curated by Paul Ardenne for the Luxembourg Pavilion), problems are considered in common terms. Throughout six rooms, drawings containing short texts are presented, including one of Karl Lagerfield wearing a Paradiso Lussemburgo tote bag with text that reads: "Imagine a culture in which artistic creation by human bodies is not subject to passing fads dictated by big money and mass media. Imagine a culture in which artistic creation supplies all human bodies with philosophical interrogations that can make life in society better."

Another drawing of men crowded onto a rubber dinghy points to the violent displacements that have turned the Mediterranean Sea into a bloodbath. Here, Marciewicz writes: "Imagine that countries are depoliticized geographical territories with individual historic cultures, respected by all human bodies."

It is at this point of the political imagination that art's impotence is unveiled, which brings us back to the questions All the Word's Futures poses when it comes to truly considering how we might move forward from this point onwards, at once together and apart. How do we mediate all the world's histories in a world currently being shaped by them? How does the Venice Biennale—and by association, the so-called art world— function as a space of agency, if indeed it has any agency left?

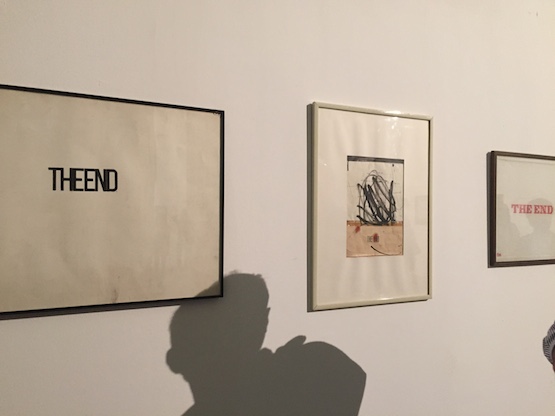

There's a reason why Marx—or at least the question of capitalism—is crucial when it comes to thinking about the problem Enwezor lays out. The first room of the Giardini, for example, contains works by Fabio Mauri that spell out "THE END" on paper, which recalls Aime Cesaire's resignation letter to the Communist party in 1956. In his disillusionment, he wrote in clear terms that the responsibility towards discovering our future belongs to nobody but us. —[O]