Frank Bowling’s Little-Known Sculptural Practice Bridges Art and Life

On the occasion of Frank Bowling's solo exhibition at Stephen Lawrence Gallery in London (15 July–3 September 2022), Sam Cornish, the exhibition's curator and writer of the upcoming book Frank Bowling: Sculpture, to be published by Ridinghouse, offers his insights into Bowling's sculptural practice.

In the late 1980s, Frank Bowling was asked by a curator from the Castlefield Gallery, Manchester if he would like to show his paintings alongside a sculptor. His response was: 'I'll do it myself!'

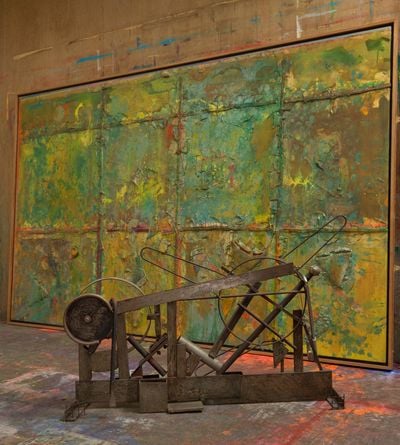

The result was a group of little over a dozen steel sculptures, made between 1988 and 1991. They were Bowling's only direct and sustained engagement with making sculpture. In the years since, many have been lost, destroyed, and stolen, or perhaps simply migrated back to the scrapheap.

Most of those that have survived have found places within the clutter of Bowling's London flat, surrounded by and often covered in the detritus of everyday life, postcards, dried flowers, or medical paraphernalia. A contemporary reviewer noted that Bowling thought a 'satisfactory criterion for sculpture is that it should look at home in the world and belong to human discourse.'

Bowling's sculptures retain a strong sense of the expedient, improvised, even rather off-hand manner in which they were made. Bowling makes a virtue of being an amateur sculptor. The pieces are direct, un-tricksey, playful, but with a surprising toughness and physical presence. They relate to the sculptures of Anthony Caro, to Cubism, and to classical African art.

Perhaps most crucially, they nod to the geometry and undifferentiated infinite spaces of early 20th-century abstract art, important to Bowling since writing his art-school thesis on Piet Mondrian. The unlikely mixture of domesticity with hints of infinity is part of their charm. I've called them a form of 'home-made Constructivism'.

Almost all made within a few years, Bowling's sculptures have a distinct and relatively limited visual identity. The idea of the sculptural contained in his paintings is more diverse, diffuse, and ultimately more significant.

My book Frank Bowling: Sculpture, to be published by Ridinghouse, charts the idea of the sculptural in Bowling's art from the early 1960s until the present. It is a complex story permeating almost every aspect of his painting, both before and after his sculptures of the late 1980s.

The objects signal a continuity between art and life and emphasise that the painting itself is a kind of object. Lines of packing foam give the works a geometric substructure, a device drawn from contemporary steel sculpture, that of Caro especially.

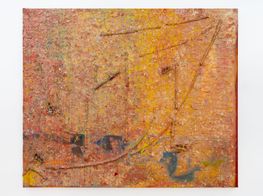

Sculpture is less immediately visible in Bowling's most recent paintings, the dramatic, surprising works he has made in the last decade or so, that I believe are some of the strongest he has ever made. If sculpture is less visible now, this is not because Bowling has rejected the sculptural but because its lessons have been absorbed so completely into his thinking.

Recently he has spoken of his desire to achieve 'thingness' in his work. For Bowling 'thingness' involves emphasising the painting as a physical object, influenced by his experience of sculpture, but is also a much broader category.

He has spoken of trying to capture the 'extemporaneous life' of things, and asserted that as 'a thing myself I was there, I witnessed, I felt, I know, and the knowing is the work.' He hopes that the thingness of painting can capture some sense of thingness in its broadest sense, encompassing the body and the world that surrounds the body.

The dream is impossible, idealistic, and beautiful, and ultimately a comfort and a way of living. —[O]

Main image: Portrait of Sir Frank Bowling (2020). © Frank Bowling. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2021. Photo: Sacha Bowling.