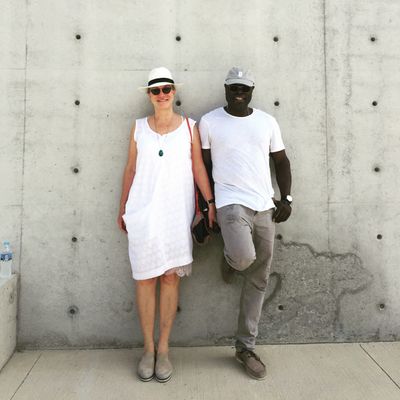

Suzanne Deal Booth and LeMel Humes on Living with Art

American philanthropist Suzanne Deal Booth has a unique understanding of the pieces that she collects. Having studied art conservation at New York University's Institute of Fine Arts and Conservation Center before embarking on a life of arts patronage, she knows what is at stake when she acquires artworks with certain materials or of certain scales.

In 2010, Booth acquired the fabled Bella Oaks vineyard, which had produced a designated vineyard Cabernet Sauvignon wine since 1976. Under Booth's leadership it was released in 2021 under its own label—Bella Oaks—and immediately sold out. The 11-hectare property has offered many opportunities for ambitious outdoor art installations.

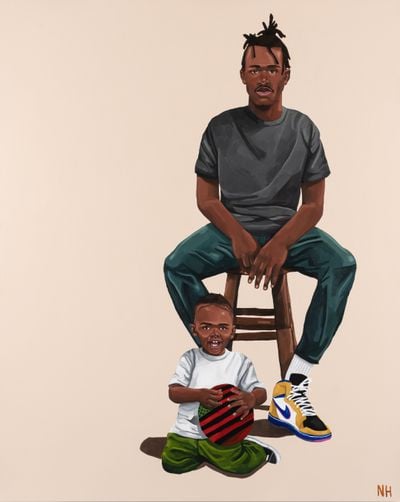

Humes, whose son Noah Humes has been making waves with his bold figurative paintings, shares his thoughts on the differences between the worlds of art and music, as well as the artworks he has most recently been drawn to.

Suzanne, what was the first artwork that you collected?

SDB: In my early 20s I would barter my editing services for artwork, fine-tuning art publications and art historical treatises. My very first artwork that I traded my services for was a Jean Cocteau print.

Do you still have it?

SDB: Yes, I do. In this case I was editing some essays for a new art advising business and I was paid with an Eduardo Chillida print as well. They're meaningful to me because they're my first works. I was probably 21 at the time.

Is art something that has always been in your life?

SDB: Yes. Early on I never really had the means, but I started appreciating art at a young age. I loved going to museums, and I also started travelling on my own in Europe.

I went abroad when I was 19 and lived for a year roaming around Europe and Turkey in a Volkswagen van, living off grid a little bit.

At the start of your collecting journey, was there a group of artists that you were focusing on or that you were especially interested in?

SDB: I was always hanging around with contemporary artists because I worked for a collector, Dominique de Menil, and the other people who worked for her were also in the art world. They were emerging artists who had art-related jobs, like framing or installation, and we were all friends and worked in the same organisations.

Mel Chin is an artist I've collected ever since I shared a loft with him back in the early days when I was still in college. Last year he received the MacArthur Genius Award. He's a super talented artist who makes art about political, cultural, and social issues.

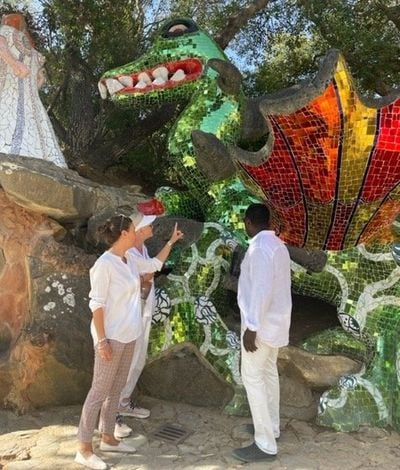

In 2010 you acquired Bella Oaks Vineyard. How did that change your collecting journey to suddenly have this beautiful outdoor space?

SDB: I quickly decided that the vineyard was a sacred space, and that I wanted to designate a defined area of my property for sculpture—a corridor of land that leads to the house on the vineyard's edge.

The first pieces installed there include a Joel Shapiro—one of the walking men, which I think looks really wonderful in that location.

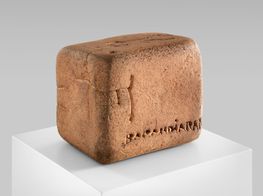

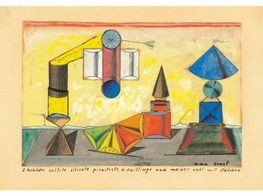

Now I have other works in this corridor, including a Bosco Sodi installation, works by Marianne Vitale, Robert Irwin, Ann Hamilton, and also a Max Ernst bronze called Le Génie de la Bastille, which is a historical sculpture from the 1940s.

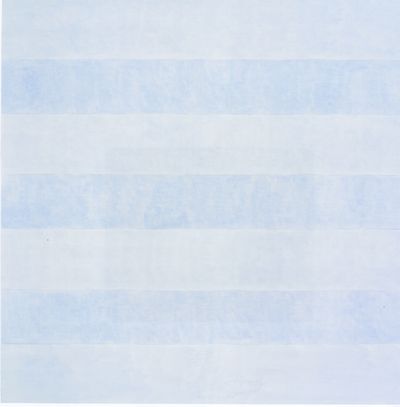

An outdoor infinity room by Yayoi Kusama was installed a few years ago in a special part of the property dedicated to that space. A forced-perspective garden leads up a hill to the Kusama installation, creating a dialogue for the artwork and landscape to harmoniously play off each other.

The Kusama is a mirrored cube so you can enjoy it from the outside, because it's reflecting everything around it, but you can also enter it and have a totally different experience.

Would you say that your experience in art preservation has made you more comfortable collecting ambitious artworks?

SDB: That's such an interesting question. Because I understand materials, I am less likely to buy art that's made out of questionable, degradable materials, though I appreciate and love them.

As long as you understand what you're getting, and you understand that the artist's intention for the work is that it might change over time, then it's fine.

Are there materials that you stay clear of, as a general rule?

SDB: Certain plastics that are just going to change with time—that start looking opaque. Photography, for example, including early Polaroids, need to be installed in low light levels and have to be rotated periodically.

Kusama's infinity room, which is titled Where The Lights In My Heart Go, is by far the most vulnerable, because it has a mirrored surface. It is important to keep it protected from the wind, dirt, and birds, and it must be cleaned periodically. It's high maintenance.

Is there an artwork that you dream of collecting?

SDB: For me it would be the artworks that I'll never be able to have—the 'untouchables'; things that are in museums, or that are very rare, like a Caravaggio, though I know it would be difficult to live with his subject matter.

LeMel, are there any artists you are interested in at the moment?

LH: Because of my relationship to my son, Noah Humes, I'd have to say he's probably the one I'm mostly thinking about because I'm concerned about his success.

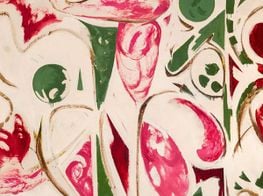

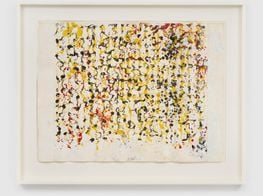

Otherwise, I would say Lee Krasner. There's a painting by her that Suzanne has, and it's the one that affects me the most. One of her umber paintings from the 60s. Lee Krasner painted it at candlelight, so when it's getting dark, it's almost as though it comes alive.

SDB: Yes, she couldn't sleep during that period—Jackson Pollock and her mother had died recently, and I think she was smoking a lot. It's almost as if there's a haze

LH: Krasner was married to Jackson Pollock, and although I love his work, I still gravitate more towards her paintings. She's really powerful.

SDB: I'm very mindful with how I hang works, and their relationship to each other and the synergy between them. I don't like violent works of art, and I'm not so keen on a lot of figurative art. I love Agnes Martin, for example, because her works have a calming effect on me.

In the bedroom we have gold ground paintings from the Quattrocento—they're saints, angels, Madonnas and child, and I feel as if they're watching over us as we sleep. In our next house, we hope to create a special room for my panel paintings as well as library spaces for all our many books.

LH: I have African and African-American history books. My father had a bookstore back in the 60s and I kept most of his collection.

LeMel, what are the perks for you living in a house filled with so much artwork?

LH: Living in a world of art—her world—I tend to learn quite a bit. It helps me talk to my son, and mention certain things I like, and it helps me communicate with people in the art world. I learn a lot from just being surrounded by art.

It must be so different to a museum experience, where you only get to spend a few seconds or minutes with a work. In this case, you're able to see pieces over and over again, and they might give you a different feeling, depending on the mood you're in, or the weather.

LH: We recently went to a place called Glenstone outside of Washington D.C., and one of the galleries beautiful Brice Marden, which I felt familiar and comfortable with because of Suzanne's collection.

If either of you could change one thing about the art world, what would it be?

SDB: The one thing I personally would like is that we all have the same mission in the arts, to learn about, understand, and be curious about both historical and very new art.

I wish there was less self-interest and less concern about the market.

Suzanne, are there any new artists you have discovered recently?

SDB: There's an artist I've known for years called Laddie John Dill from Los Angeles, but I've only recently gravitated to his new work. I'm open to everything. Charline von Heyl is a talented artist I like to follow, who has a studio in New York and Marfa. Eva LeWitt is a young new artist whose work I've just fallen in love with as well.

Many of the artists that I got to know very early in their careers are ones I've had the opportunity to stay in touch with and see their work develop. I like to follow their work, because I feel closer to them, like Edmund de Waal, Judy Fox, Charline von Heyl, Mel Chin, and Elisabetta Benassi.

I'm the patron and the buyer at times, but mostly I'm more the curator type. I've worked in many museums and feel very connected to curatorial work.

Of course, now that I have a business with something to sell, I can be equally annoying. Like, 'Oh! You guys wanna buy my wine?' All of them are trying to sell me art, yet I don't see them scrambling to buy my wine, and my price point is much lower! [laughs]

LH: There are a few things I would change about the art world, though it mostly has to do with the state of the world in general and particularly America. There's no accessibility for African-Americans and people that are not in the financial bracket to see and be exposed to such great art.

For example, you never see a really cool art centre in the centre of a Black community, and that's something I would want to try to change. I think that's something that can be changed, without putting too much emphasis on finance.

Recently there has been this trend in the market towards young Black figurative painting, but you were telling me that at art-world events, you're often the only Black person in the room.

LH: I think it has a lot to do with the history of the past. When you look back to the Caravaggios and Leonardos, you don't see Black faces. So you have hundreds of years of art that is celebrated and studied, and within that there are no African-American faces.

Artists of today are trying to flood the world with images that were not being seen back in the 18th, 17th, and 16th centuries. I can understand why more African-American artists are doing figurative things, because of the void that has existed for so many years, and the real need to identify.

Suzanne, has your approach to collecting changed since you met LeMel?

SDB: Oh yes. We do everything together. A real eye-opener for me was when we were at Frieze, and they had a lot of off-site visits to African-American collections, which was the highlight for me, to see the depth at which these collections have grown and how these communities are supported.

LH: Yes. We also went to three different homes where my son's work was showing, and that was very touching for me.

LeMel, since meeting Suzanne you have experienced that inner circle of the art world, but your background is in music. How do you find the art-world elite?

LH: I find it very segregated. There's just not an equal percentage of African-American buyers or people who appreciate the work.

SDB: There are more and more Black collectors, but they're not as visible on the international art scene. In L.A., for example, you'll have more Black collectors because there are more Black artists working in L.A.

LH: There's more Black wealth in L.A., because of the entertainment and sports business.

Would you say that is different in the music industry, where your background is?

LH: Yes, the difference is accessibility. Most people listen to the radio, and they listen to and are influenced by music, but they're not exposed to much art.

I also tend to find that in the art world there's another level of education that is more prevalent than in the music world. When I go back to my friends in the music world, I start telling them about the art world and it goes over their head.

It's just because of exposure. I grew up with art books all over the house and I would go to art galleries like once a week, but my musician friends didn't do that. Exposure in the art world is not as it should be. And that's just a matter of accessibility.

To finish, I want to ask you both a few questions about your favourite platforms for art. What are your favourite art Instagram accounts?

LH: I have to go back to my son. I know that's biased, but it is my favourite. Also, Hans Ulrich Obrist, because he meets such a range of artists of different ages. His is very eclectic and interesting.

SDB: Dave Hickey, who's not with us anymore—for about two years had an art account that was fascinating. He's such a great writer.

What are your favourite galleries?

LH: One of my favourite galleries is Hauser & Wirth, because I've had the freshest experiences at their exhibitions, whether in Somerset or Los Angeles. The way that they set up their shows is really on a top level.

SDB: I like Hauser & Wirth as well. Of course there are the big ones that offer such an amazing range of great artists, like Pace Gallery and Gagosian. If I'm in New York I go and see a lot of the galleries. I like Petzel, Kasmin, Lisson Gallery, Regen Projects, and even smaller galleries and independent dealers such as James Barron and Fairfax Dorn Projects.

What are your favourite art museums?

LH: I would say the best experience I've had at an art museum was at the Bilbao Guggenheim. Everything was really powerful there.

SDB: There are museums that I'm very familiar with and they feel like home to me. I love the Metropolitan. But if I'm in Europe, it's probably going to be a tossup between the Louvre or the National Gallery in London. I'm very familiar with their collections.

If I had one museum that I could only go to for the rest of my life I would want something encyclopaedic so I could learn about art, so it would have to be the Louvre.

Additionally, I love The Menil Collection in Houston by architect Renzo Piano and the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth by Louis Kahn. I also worked in both these museums, and the collections make me feel at home. —[O]

Main image: Yayoi Kusama, Where the lights in my heart go (2016). Mirror-polished stainless steel. Installation view: Bella Oaks Vineyard. Courtesy Bella Oaks Vineyard.