This exhibition took place when the gallery was previously known as Choi & Lager.

At 85 Rose Wylie is known for two things. First, being born in 1934 but remaining pretty much below the radar until she reached her seventies. She doesn't care much for this story, even if it has made good copy. No, what matters is the second thing: having a string of solo shows, including at the Tate and Serpentine galleries, colourful, large-scale, figurative paintings on unprimed canvas that are unarty but intelligent, funny and quietly political. They appear aesthetically simple, but the abbreviated and apparently casual style generates a raw immediacy that critic Mel Gooding describes as 'at once visual, tactile, mental and emotional.'

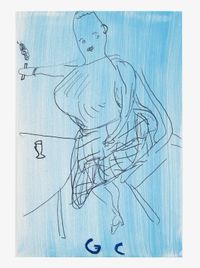

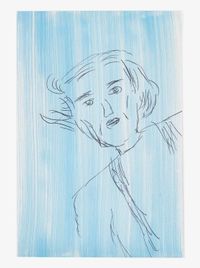

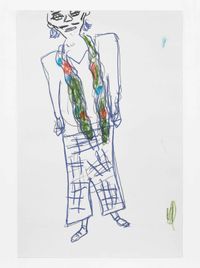

The paintings here are made after diaristic drawings which Rose says come from memory, observation and 'conceptual projection–how a stereotype would look from an un-stereotypical point of view'. They call on a wide range of cultural references from history, fashion and cinema, to mythology, sport and literature. High and low come together exhilaratingly, which is very much how Rose is: visitors to her rambling studio in Kent are quite likely to be offered sausages and champagne. The threads linking these disparate fields are not in the subject matter: they are in a discriminatory process about decisions of visual quality, held together by an aesthetic formed over decades. Those qualities can turn up in the least expected subject, released by Rose's enthusiasm, and her interest in how images evolve, transform and accumulate meaning–how they become familiar, iconic and part of the narrative of popular culture and wider history.

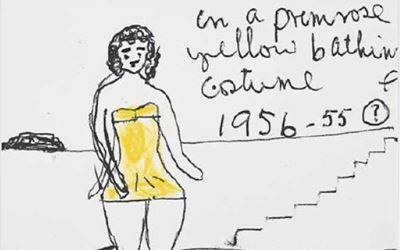

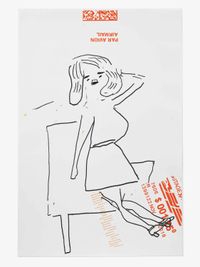

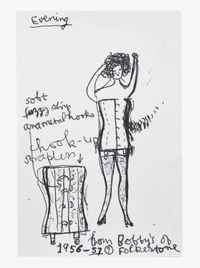

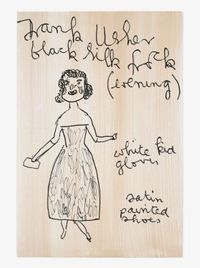

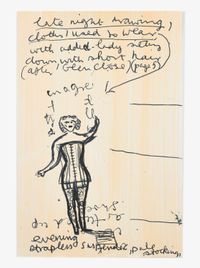

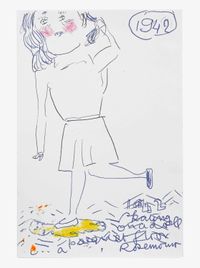

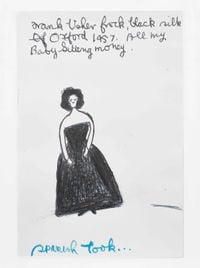

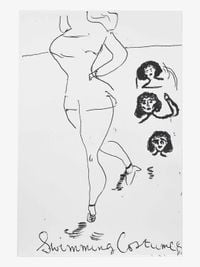

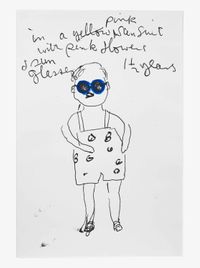

Memory is the focus of the charming 'Late Night Drawings' in Girl Now Meets Girl Then, made in what Wylie calls a 'use the pages' notebook which handily settles the question of how many to include. Its reproduction in that unpretentious format matches the spontaneously characterful style of the drawings and associated notes, with their irregular lettering, crossings out and extra insertions–changes of mind which might echo the notoriously tricky business of deciding what to wear on a night out. The drawings and free-wheeling words also convey how untidily memory can work. In Jennifer Higgie's words 'if time is not neat in her pictures, this is because it is, by nature, a messy thing'.

Rose loves watching people. Escalators are ideal, she's said, as 'you can really stare at people. On a train, you're asking for trouble if you stare–but on escalators, they're going the other way'. Here, she seems to be looking at her past self, the Girl Then of the 1940's and 50's–in the same spirit. Or is she? Actually, Rose says that the girl isn't her. Indeed what interests her, she continues, 'is the dis-connect of the clothes with the girl (who is not me... those are not my legs) and trying to find a new and particular look-of-face, and specific but different shaped legs, and legs that do not exactly fit how the media seems to think they should look'.

So it's the experience of the clothes which comes to the fore. The Frank Usher black silk frock from 1957 which cost 'all of my baby sitting money', but was never worn (the first black drawing of it 'clicked for me', says Rose, 'with Mexico or Spain'). The primrose yellow swimming outfit–Wylie stresses that 'all the colours of clothes in the paintings are what they were'. The strapless corset from Bobby's of Folkestone in 1956 or 1957: Rose isn't sure about the dates, but sure about the garment which–though described as 'the modest corset' in the related painting–'was seductive rather than restraining'. Going back further, a birthday present from 1943, knitted by Daphne as part of the war effort by using up different coloured wools.

As is typical of Wylie, the drawings and notes then inform paintings which reach a comparable energy, freedom and attitude through different means. She says that she 'likes awkward' in paintings, even if she may have looked elegant in the clothes. What she likes are 'the decisions that never stop coming... how much of everything, how much contrast, how stupid, how tight, how loose, how desperately, well, awkward'. Rose will, for example, 'add a bit of canvas on the bottom of a painting, and/or stick a bit on (for try-out or correction) for feel-free and flexibility' and mentions liking 'the previous-use crumples' of one collaged section which 'had been used first to cover an ugly cushion and was well sat-on'. She also goes for 'the thick/thin paint contrast, the flat/worked contrast, the slosh/tight handling contrast' and particularly, 'the painting, not the story'.

That last point is important. Wylie's paintings aren't essentially 'about' something else, they're about painting, and how it creates her distinctive way of looking at her subjects. We're aware of memory, observation, and the inhabiting of clothes, yes–but what we're really looking at is how Rose's unique painting style reflects her unique way of seeing the world.

Press release courtesy Choi&Lager Gallery. Text: Paul Carey Kent.

12 Eonju-ro 165-gil

Gangnam-gu

Seoul

South Korea

https://www.jarilagergallery.com/

+ 82 (0)10 8191 5834

Wednesday–Saturday

1pm–6pm

and by appointment