Curated by Hettie Judah, this online exhibition is the gallery's first presentation of work by the provocative feminist artist Alexis Hunter (1948–2014) since announcing representation of her estate. The two-part exhibition features never-before-seen paintings, prints and photography. It follows the 2018 presentation of Hunter's work at Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, her first solo show in London since 1981. Part 2: Callisto, also curated by Hettie Judah, launches on 7 December. View the online exhibition by visiting the gallery's website www.richardsaltoun.com.

With gallery doors closed due to the recent lockdown brought on by COVID-19, it is satisfying to picture Alexis Hunter's rowdy, seductive output in such close proximity to London's long-awaited Artemisia Gentileschi show. 'If you bury yourself in Artemisia's golden folds, you know she really loved painting,1' Hunter observed after her own return to painting in the 1980s. Artemisia was one of the influences she cited as a painter, together withFragonard, Monet and Goya,2 so she was shy, apparently, neither of pleasure, nor horror.

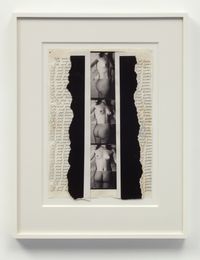

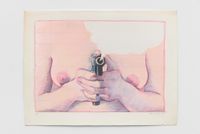

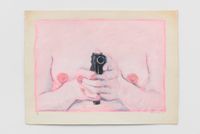

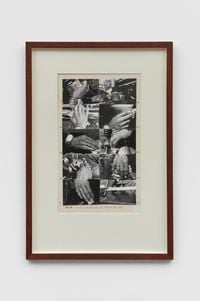

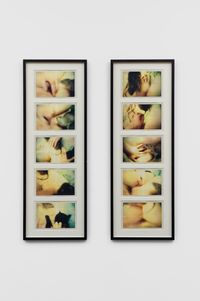

After moving to London in 1972, Hunter worked with photography, often in series resembling animation cells or picture stories. She hoped to engage an audience beyond the art world hardcore by co-opting the aesthetic devices of advertising and women's magazine as a vehicle for feminist theory. Sex, violence, and the threat of sexually violence were themes she returned to: even before Hunter rediscovered the pleasure of painting, the fantasy of lavish bloodshed that Artemisia composed for her muscular heroines must have felt thrilling.

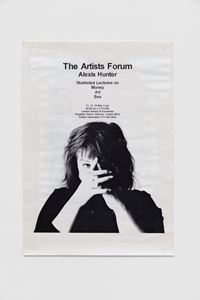

Hunter used the title Money Art Sex for a lecture at the LSE in 1993: like so much of her work, it was punchy but far from simple. 'One aspect of my populism was to make images that appealed to the part of the brain that snaps to attention on seeing the fetish–the mother's shoes and the fur for instance–and danger–fire, sharp objects, cracks, blood [...] the important thing was to get people to look at the work in the first place,' she explained in 19973.

Hunter really was interested in the relationship between money, art and sex–how art used sex to generate money, how money dictated how sex manifested in art, how this patriarchal power dynamic persisted in advertising, Hollywood cinema and glossy women's magazines. After exploring it through photography and film in the 1970s, in her painting and printmaking Hunter followed the power dynamic further, back to European myths and the creation stories of New Zealand.

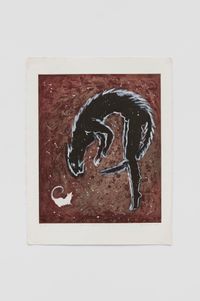

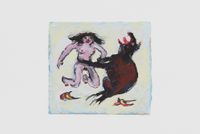

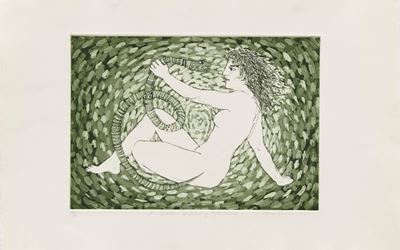

Hunter's new mythology–her cosmopolitan pantheon of goddesses, muses, devils and beasts–evolved as an act of re-telling, or perhaps an exorcism. Her destabilised mythic power structures are expressed in chimerical creatures–their bodies composed of multiple species–that she described representing 'inner human conflicts, just as artists fantasised about the unknown in medieval times4.'

A goddess confronts patriarchy: she is naked and magnificent; he a great serpent, phallic, coiled, bejewelled. She looks apt to bite.

1 Artist's Statement, Camden Town (1982) cited in Elizabeth Eastmond. Alexis Hunter: Fears/ Dreams/ Desires (1989)

2 Catalogue for the British Council exhibition Fantasy (1994)

3 Interview with John Roberts in 'The Impossible Document: Photography and Conceptual Art in Britain 14' Catalogue for the British Council exhibition Fantasy (1994)

4 Catalogue for the British Council exhibition 'Fantasy' (1994)

Press release courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery. Text: Hettie Judah.

41 Dover St

Mayfair

London, W1S 4NS

United Kingdom

https://www.richardsaltoun.com/

+44 207 637 1225

Tues - Fri, 10am - 6pm

Sat, 11am - 5pm

Alexis Hunter, A Goddess confronting Patriarchy (1983). Etching. 38 x 56 cm. Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery.