Since the 1990s, Brook Andrew has worked with archives and collections to address themes of colonialism, historical amnesia and indigenous cultures. Of Wiradjuri and Scottish ancestry, the artist's interests in forgotten histories began as a child, when he wondered why popular Australian culture seemed uninterested in representing his Aboriginal heritage. Using multimedia creations as conduits to revisit the past, Andrew offers alternatives to dominant Western readings of the world.

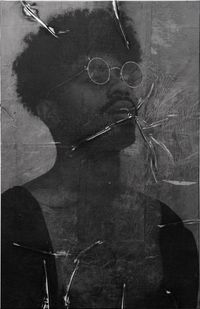

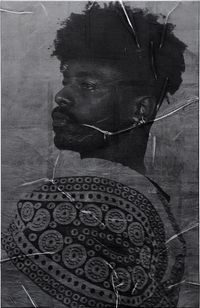

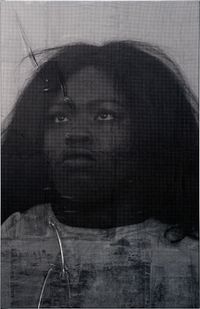

Read MoreMany of Andrew's works incorporate 19th- and early 20th-century photographs of indigenous peoples, as can be seen in his 1996 piece Sexy and dangerous. For the work, Andrew enlarged a small found portrait of an unnamed Djabugay man from North Queensland to larger-than-life size, emphasising the figure's authority in the process. At the same time, Andrew exaggerated the man's body markings so they appear to segment his body into pieces, alluding to the historical erasure of Aboriginal people in Australia. The conflicting descriptions 'sexy and dangerous' in English and 'female cunning' in Chinese are written across the man's chest, further referencing the fact that colonial photographers habitually neglected to record their sitters' individual identities. Through images that directly address the colonial past, Andrew brings forgotten people and their stories to light. As the artist explains in Ocula Magazine, his practice consists of asking: 'How is it that we can look at such difficult narratives and histories, but also in ways that are informative?'

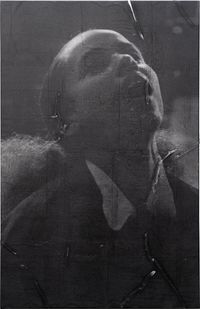

Andrew's concerns with disrupting conventional narratives and advancing invisible histories continued in 52 Portraits (2013), a solo exhibition at Tolarno Galleries, Melbourne. The show featured 52 multimedia portraits of anonymous individuals from Africa, Argentina, Ivory Coast, Syria, Sudan, Japan and Australia. By borrowing the title from anatomist Richard Berry's 1909 book Transactions of the Royal Society of Victoria—Volume V of which included 'Fifty-two Tasmania Crania'—Andrew confronted the practice of collecting Aboriginal skulls, which lasted into the early 20th century. Widely believed to be part of the most primitive race of the world and a 'dying species', the skulls of Tasmanian people were robbed from graves and studied by medical students. The images in the exhibition were based on 19th-century postcards Andrew had collected. Similar to the images he had used for Sexy and dangerous, the individuals' identities had long been lost.

In 2015, as part of the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT8), Andrew presented Intervening Time. For the project, he removed colonial-era artworks from Queensland Art Gallery's Australian Collection Galleries in order to paint the walls with the traditional chevron patterns of the Wiradjuri people in deep red, blue and black. The artworks were then mostly returned to their original places in the galleries, along with the addition of six of Andrew's own works from his 2012 installation Time (2012), which includes enlarged archival photographs and considers the impact of European settlement across the world. By juxtaposing traditional Wiradjuri patterns and colonial works, Andrew reminded the viewer of the forgotten history of Aboriginal people and their existence in the contemporary Australian narrative. In a recent interview with Ocula, the artist explained that the motivation behind his foregrounding of marginalised narratives as 'alternate histories' stems from a desire to offer alternative interpretations to the traditionally demonized 'other', in his case the Aboriginal people of Australia.

Andrew's work continues to challenge established narratives. For the 21st Biennale of Sydney, he collaborated with four artists from various backgrounds to create What's Left Behind (2018), an installation that considers the idea of memory in objects. Consisting of five sculptures, serving as alternatives to the traditional museum vitrine, the work displayed artworks and objects from the collaborators' personal archives alongside items from the collection of Museum of Applied Art and Sciences (MAAS), Sydney. In juxtaposing personal and collection-based objects together, Andrew reveals how memory and individual stories imbue objects with meaning.

Unrestrained by discipline, Andrew also works as a curator. In 2012 he presented Taboo at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, which featured works by Australian and international artists. Examining the range of taboos across different cultures, the exhibition also explored the idea of censorship. For another 2017 exhibition titled Ahy-kon-uh-klas-tik, Andrew visited the art collection at the Van Abbemuseum, Holland, to reconsider the Western art canons in relation to indigenous history. The title—the phonetic spelling of 'iconoclastic'—not only references Western dominance in the modern world but also the historical linguicide of Aboriginal languages in Australia. Against the walls painted in black and white stripes—a motif influenced by Aboriginal carving traditions—Andrew juxtaposed the works of prominent artists including Pablo Picasso, El Lissitzky, Gabriel Orozco, Nilbar Gures and Mike Kelley.

Andrew completed his studies at Western Sydney University (1993) and The University of New South Wales (1999). He has held solo and group exhibitions at major institutions, including Tate Britain (2015); Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (2012); National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul (2011); and the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC (2007). His works were also part of the Biennale of Sydney (2018, 2010) and Shanghai Biennale (2012). In 2016 Andrew received a three-year Australian Research Council grant and produced Representation, Remembrance and the Memorial (www.rr.memorial), a project that responds to the calls for a national memorial to Aboriginal loss.

Sherry Paik | Ocula | 2018