Alain Servais: 'I'm very careful about not offending anyone'

Alain Servais. Courtesy Alain Servais. Photo: Michel Loriaux.

Alain Servais. Courtesy Alain Servais. Photo: Michel Loriaux.

With a mind for the world of investment banking and finance and an eye for art that speaks to our contemporary moment, Brussels-based Alain Servais has an art collection that is raw and unsettling, yet equally compelling.

Servais has been collecting for over two decades. He largely buys underrepresented art he thinks is significant and worthy of preservation, by artists who raise difficult questions about materiality, corporeality, violence, racism, and death. He sees himself as a custodian of works that reflect larger sociopolitical conditions, rather than that which is representative of personal taste, and is guided by anthropological theories by the likes of Claude Lévi-Strauss and Edgar Morin. Some of his earlier acquisitions are visceral in quality, yet despite his penchant for the performative, his collection also incorporates minimalist, conceptual, and moving image works.

Servais, who is averse to painting, primarily gravitates towards sculpture and installation, and has a strong interest in video art and new media. He currently owns a website of hypnotic, morphing geometries by Rafaël Rozendaal, for instance, and his latest video acquisitions include an absurd work by Adrian Melis, titled Engagement Rate Formula (2019), proposing to humanitarian organisations to materialise social media 'likes' into hundreds of plaster casts as a form of refugee aid.

Other recent works include Broomberg and Chanarin's operatic visual documentation of a boat graveyard—the glaring residue of migrant groups arriving from North Africa (The Bureaucracy of Angels, 2017).

Servais doesn't come from a family of art aficionados and often attributes his journey into art collecting to a series of accidents and chance encounters. One of these includes meeting his childhood friend, Christophe Van de Weghe, who gave up his career as a professional tennis player due to a sports injury, and ended up working in sales at Gagosian in New York. This opened Servais up to the inside dealings of the art world.

From 2000, the 900-square-metre industrial space, known as The Loft, a converted factory, has been showcasing an annual curated exhibition from the Servais Family Collection—and since 2010 the space has doubled as an artist residency. Located in Schaerbeek, home to a diverse population of immigrants, it's a fitting location for a collection by someone who is drawn to art for its ability to spark encounters with otherness, and instill a certain sense of curiosity about the world.

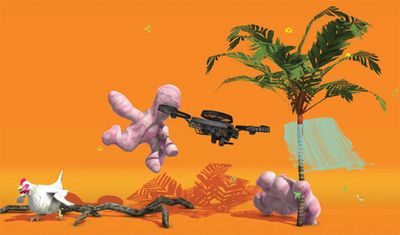

AMEXICA, The Loft's exhibition showing until May 2021, addresses Mexico—against the backdrop of the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement—and how territoriality plays out beyond geopolitical divisions through works by Nina Beier, Christian Camacho, Renato Garza Cervera, and Ariel Orozco, among others, curated by Marisol Rodríguez.

As far as private collectors go, Servais is public-facing, happy to voice his discontent to the press and active on Twitter, where his feed mixes art news with global politics. He has long argued for more transparency and the adherence to best practices in the art market and is an outspoken critic against the market's endemic and self-perpetuating inequalities.

Although Servais is adamant that he doesn't buy art at art fairs, this January saw him in Mumbai for Mumbai Gallery Weekend (9–12 January 2020), February in Mexico City and Madrid for Zona Maco (5–9 February 2020) and Arco Madrid (25 February–1 March 2020), respectively, and March in New York for The Armory Show (5–8 March 2020). And while he has limited his travelling to Europe due to the spread of the coronavirus, his hunt for art that pushes him out of his comfort zone is still relentless.

In the past month, he has travelled to Riga for the second edition of RIBOCA, the Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art (20 August–13 September 2020), to the 11th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art (5 September–1 November 2020) and Berlin Art Week (9–13 September 2020), to Manifesta 13 in Marseille (28 August–29 November 2020) and later this month to Vienna, for the gallery festival curated by (8–26 September 2020) as well as viennacontemporary (24–27 September 2020).

The following conversation has been transcribed and edited from a sprawling conversation held in late July 2020 that endured for half a day via Zoom, upon Servais' return from Paris Gallery Weekend (2–5 July 2020).

NKAlain, the last time we had such an extended chat was over a year ago at the 58th Venice Biennale (11 May–24 November 2019). How have things changed for you since then?

ASI don't think much has changed, except for travel. I've lived in confinement before and I think a good collector is someone who is very lonely, like an artist. For me, a good artist is someone with a fracture or a wound, who has managed to survive by making something out of it. Collectors are not so different; they are strange people. When I am home, I read for seven to nine hours a day and I don't interact with humans much—it's hard to live with me.

But movement is a real problem now... I was reading that there's a shortage of bikes worldwide. I know it's true because I need to replace my brakes and it will take two weeks. If you want to make tonnes of money, learn how to fix bikes, open a bike store, and I'll be your first client.

NKYou are well-known for your bipedal appearances at art fairs and biennials. Jokes aside though, how do you think the pandemic will affect the art world?

ASI read recently that the crisis is reinforcing existing trends. Gallerists are actually relieved to have escaped this rat race by accident, and I think it's fascinating that everyone from Kamel Mennour to Emmanuel Perrotin have said that they were so unhappy with the way things were. It's an absurd world we live in, where the Art Basel Miami Beach Convention Center has become a hospital, and it might be prolonged beyond September.

I was raised to become an investment banker, and finance is very much about herd instinct and movements, but artists have the capacity to raise consciousness about issues we aren't cognisant of in the world of finance.

Gallerists are individualists—they are the worst businesspeople I have seen in my life. Although they have an opportunity to bring business back, and are currently reducing their costs, they're completely frozen. They are going to be shot down and eaten alive by the auction houses that are doing a much better job—that's where the easy money is. On the other side of the spectrum, where the young collectors are going for lower prices, Artsy is taking over. So gallerists are squeezed somewhere in the middle. What's left for them? Spending their money to go to art fairs? This was described to me recently as placing chips on a roulette table. They, especially the mid-sized galleries, are taking a huge risk and they don't know how it will go. There's nothing worse for one's health than not having control over one's future.

NKThe fact that we even have control is an illusion but at the moment, uncertainty is looming on a pervasive and global scale.

ASThe capitalists are thriving, however. I'm ashamed to say this but since January, my portfolios have gone up by 19 and 23 percent.

NKIn which areas?

ASMainly in the U.S., with funds in Apple and Microsoft. Also with Beyond Meat.

NKHave you been buying more art?

ASYes, I feel a responsibility to do so. I've recently bought work by Héctor Zamora, Cindy Sherman, and Bodys Isek Kingelez, who builds these architectural models, as well as work that I saw in Berlin a few years ago by Saule Suleimenova, a Kazakh artist, among a handful of others. My spending is about the same though, because I don't buy at art fairs. In Paris, I could have bought a couple of works, but one is reserved by the Pompidou and I'm still following up on a work by Kapwani Kiwanga.

NKWhat led you to collecting?

ASI never decided to become a collector. Like the allegory of Plato's Cave, it became a way for me to gain awareness. I was raised to become an investment banker, and finance is very much about herd instinct and movements, but artists have the capacity to raise consciousness about issues we aren't cognisant of in the world of finance. I realised when I was 14, during my studies of Latin and Greek literature, that I had an outsider way of thinking. It was causing trouble with my courses in religion at a Jesuit school. I often go back to Socratic questioning and it's because of this constant questioning that I have a pretty dark view of the world.

NKSo your starting point is doubt?

ASWhen you question everything you think you know, you'll get to an interesting position. Socrates was condemned to death because he was too critical and pissed off many people, which is what I do today. For me, art offers a point of view that doesn't reflect the mainstream. I like artists who teach me something. That's why I enjoy investment banking, because I learn something every day from finance.

NKYou once told me that people criticise financiers for being in the art world, but finance is the lens through which you understand the world. One needs to comprehend how the world works and have a sense of the future in order to be successful at both art and finance.

ASAbsolutely. I've spent the last few months reading until 2 am to try and make sense of what direction we are moving in the financial world. One of my pet peeves is speaking to people in the arts who don't have knowledge or don't read the papers.

NKThe business world is better regulated though; the art world is heavily criticised for its opacity. So what brought you from the world of finance to the world of art?

ASAfter spending time on Wall Street and in car races during my twenties, living at 200 kilometres an hour, I found serenity passing through the doors of museums. I realised that such visits improved my quality of life and decided to recreate this museum feeling at home. My intention has always been to buy museum-quality works. The media that I started collecting at the time was photography because it could be reproduced to museum standards. My intention has always been the same: to buy works of art, which deserve to be preserved, just as museums preserve the history of today.

NKYou've written a lot about your concerns with reproducibility and distribution, which began with the medium of photography and continues with video art.

ASYou've just opened Pandora's box. Centuries ago, people were collecting unique works of art. Then came photography, and the French created a law to limit the number of editions available so that it still qualified as art. This is ridiculous because photography is made to be reprinted. I'm not in favour of limited editions, as I'm against the rule that scarcity equates to value. I mean, look at the museum of fakes that opened in Hong Kong.

NKThat's more related to the experience economy and how not everyone can travel to experience a real Monet in its original setting, for instance.

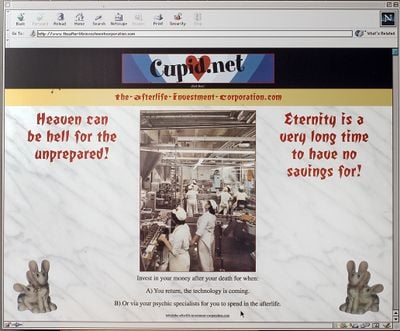

ASThe point is we now have the technology to recreate these works. The art world is lagging behind with its lateral thinking. You know how you cannot enter the Lascaux cave anymore, so they built a replica near it? You can't even tell the difference between the two. The website I bought five years ago by Rafaël Rozendaal includes a signed contract specifying that I will maintain it to eternity at my own cost. Once you link to it through your browser, it mentions that it's the property of the Servais Family Collection, and I must make it available to the public. If someone wants to project it in their interior on a dedicated screen, they can. They can enjoy my work of art in their house. So I paid USD $7,000 for something that I will never fully own, in the sense that it won't be mine alone. It's my duty to make it publicly accessible.

As the collector of this work, the only thing I'm doing is basically sponsoring public sculpture. It's as if I were putting it in your garden or in a public square. The ethos of my collection isn't about ownership, but about sharing and insidiously trying to transform you without you realising it. The hope is that maybe the works, as a reflection of my vision of the world, will change you.

NKWhat do you think is transformative about art?

ASHumans are part of the natural order; we aren't that different from animals. In today's world, the virus is showing us how fragile we are—and the economy too. We are subject to climate change and suddenly, we are no longer the kings of this world. We are dependent on nature and I enjoy works of art that point to that direction.

NKYou first began collecting in 1997. What can you tell us about the early years?

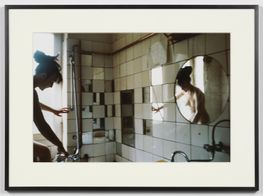

ASI cried when I saw Nan Goldin's work in a slideshow at the Whitney Museum. It was completely astounding, and her best medium by far because she mixes the visuals with music. The intensity hits you every 20 seconds. She is a photographer of love, enacting an exchange of love with her subjects, whether they are drug addicts or sex workers. I am still buying from that series, 'The Ballad of Sexual Dependency' (1986). It's extremely important for the history of art. It's as important as Arthur Jafa's film, Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016).

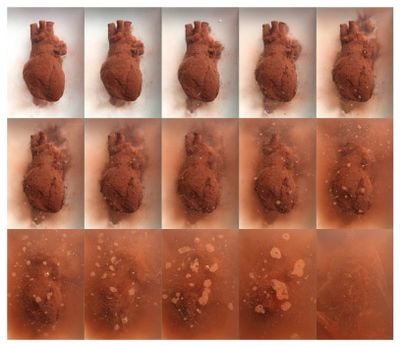

When I bought photographs from Andres Serrano's series, 'A History of Sex' (1995–1996), I was very interested in our strange relationship to the body and how it was changing. Twenty years ago, a quarter of the people on Ibiza's beach were naked, including me. We didn't mind then, but if my daughters had to go topless today, they would feel violated. This shift affected what I was buying at the time, looking at how beautiful and extreme sex can be, and also how beautiful death can be, which is nothing other than the body put in different circumstances.

NKFunnily, you just answered my next question on how you move between drives of sex, greed, and death and the humanist impulses that motivate you to share your work. Do we need to see your collection in terms of this duality?

ASI can say that in the beginning, some were horrified by the strong focus in my collection, questioning me about placing such works in my daughters' rooms. But the collection has shifted to more social and political concerns. Quentin Tarantino sensitised me to African-American art, and that was 20 years ago.

What is significant in the preservation of art, which you'll realise at museums, is that what is preserved isn't necessarily the most beautiful, but what is considered the most relevant—in other words, what changed societies at the time. So what can we say about the year 2000? The internet, the world's relationship to Islam, the emergence of minorities, our relationship to gender, and ideas around inequality all gained prominence.

At this time, my eye was attracted to any artist dealing with these key social developments in an intelligent way, asking the right questions, as Bouchra Khalili does with migration issues, or Sophie Calle in relation to reality TV. These threads will reappear. I think that in the past couple of decades, I've become good at identifying the works that are making a difference.

NKSo it's a form of contemporary narration where you look for works that are going to make history 20 to 30 years down the line?

ASThirty years is a benchmark to see if the work will still hold its ground and whether it will be worth anything in art history. My starting point is the knowledge of significant movements happening in the world right now. Uli Sigg began his collection from the realisation that something was going on in China in the 1980s, and no one cared at the time.

I'm saying that there's something happening with digital art. And there are works of art that cannot be preserved in the Middle East because they are too critical of Islam. For example, Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde had beautiful works at MiArt using 16th and 17th-century poems, which were extremely sexual in content. I kept them for a year because they couldn't be brought back to Dubai or they would be taken into custody.

The ethos of my collection isn't about ownership, but about sharing and insidiously trying to transform you without you realising it. The hope is that maybe the works, as a reflection of my vision of the world, will change you.

Anthropologically, you'll notice that it's often a foreigner preserving a nation's art, because it is the outsider who notices the cultural specificities that are normalised by those on the inside. A big part of the collection looks at minority politics, because I realised it's one of the only ways in which you can judge a society. There are probably 149 countries in the world that define themselves as democracies, but the difference between the U.S. and Belgium is that we respect all our minorities.

I once had a Twitter fight with a writer from the Washington Post regarding a headline about the killing of children in Belgium, which referenced euthanasia as a practice that occurs, even if it's against the will of the parents. This means that if you have a degenerative disease as a 16-year-old, you can choose to die.

NKIs there a part of you that enjoys this anthropological encounter with the 'otherness' you mentioned, with what disrupts your reality?

ASTotally. I am obsessed with otherness. Like how I'm a good personal shopper for women, because I'll always take them to places they wouldn't dare to go to. If you want to make me run away from any party, put on music from the 1990s. I'm extremely allergic to nostalgia—I want to hear the music of today. My attraction to contemporary culture is this otherness and as soon as it becomes mainstream, I'm no longer interested.

NKWhat is it about conflict or tension that impacts the quality of art?

ASMy experiences around the world have taught me that good art always comes from a place of friction. Where there is no longer this sense of friction is in the West, because money has taken over. That's the part of the art market that I like to speak about: macroeconomics. The art market is where supply meets demand. What is happening in the market is that you have 40 million artists and 40,000 collectors. It's the buyers who determine the price. With this imbalance between supply and demand, artists will take anything. This doesn't mean that everything is cheap, because some artists manage to create artificial scarcity.

The art market side of things is completely separate from the collecting side of things though, which is why I don't normally discuss both aspects in the same interview. So how do you distinguish the offer from the demand? By applying the essential rule so well put by Leo Castelli, in relation to the fabrication of myths. He said his responsibility was 'the myth-making of myth material—which handled properly and imaginatively, is the job of a dealer'.

The crucial thing to understand is that artists like Anish Kapoor built a myth around themselves—it's like Kim Kardashian selling her oversized underwear for USD $20,000. You now have a series of conglomerates—maybe ten—that specialise in the business of myth-making and do it very well, such as Gagosian, David Zwirner, Kamel Mennour, Perrotin.

The Art Newspaper ran this piece that stipulated almost one third of solo shows in U.S. museums were organised by the same five galleries. I wrote an article in SFAQ, titled Art in the Shadow of the Art Market Industrialization, that explains this. You have a group of 150 artists, amongst them Damien Hirst, Rudolf Stingel, Takashi Murakami, Anish Kapoor, who are rolling over because it's not always the same. They're all going down in the market, when they were superstars a decade ago. I can tell you that Kapoor is finished, if you look at the number of sales at auction that are not happening.

Then you have some artists who are ascending, like Grayson Perry, African-American artists, female, and transgender artists. It's a fashion business, and you still have 150 artists making 50 percent of the turnover. Then you have tonnes of artists with no gallery representation.

When you question everything you think you know, you'll get to an interesting position.

There's nothing worse than a bitter artist. The artist cannot produce what the market doesn't want—money wins. So my main concern is how to preserve art in the shadow of art market industrialisation. I'm not trying to change the industry—that's impossible.

The only thing is, until the industry collapses, what insect will emerge from the mud to represent the art of tomorrow? We need that seed, otherwise there will be nothing left. How can we preserve this small thing that doesn't even constitute 100th of the size of the industry? All people that are interested in that preservation need to work together, not against, the big machine, and in its shadow. It's the only way to survive.

NKCan you explain your proposal for an artist's agency?

ASThe principle behind the agency is that we are moving from Castelli's time, when he was paying his artists a stipend, to a place where galleries no longer represent artists in the same way in the sense that they want to organise, say, curated group exhibitions, and sell what they think will be successful tomorrow, rather than be burdened with works that were good ten years ago. They don't want to take care of artists' careers or their research in Antarctica, for instance.

As an artist, if you cannot trust galleries to help you with your career, there's a continuous conflict of interest, even at the highest level. So you need to build an infrastructure like the actors did with studios in the 1950s, since they could not make movies other than those they signed with. But then they realised the agents were coming for them and not for the studios. So the power dynamic changed and the artists made their own decisions. The cinema industry teaches us that the artist agency could have huge potential.

The key to the success of any business—whether it's car-building, T-shirt-producing, artificial intelligence, or solar panel development—is economies of scale. As an artist, you can build your own studio but it's very expensive, so why not create a core structure that functions like a studio—what I call the social secretariat—which includes contracts for commissions, exhibition, consignment, as well as VAT, social security, tax statements, and all the legal elements.

NKWhat about the collector becoming a commissioning agent?

ASIt is possible because an extension of my artist agency idea is a production company, which can produce works for biennials like Venice, rather than relying on the galleries for that.

NKLet's talk about Twitter. Why do you do it?

ASContrary to what it might seem, I'm very careful about not offending anyone. Adam Lindemann was very active on Twitter but made a few mistakes and got burned down. If you overstep the mark, social media crushes you and becoming a target is unbearable. I posted news of Murdoch's son taking a significant share of MCH Group and as you know, there's a large segment of the art world that doesn't want Murdoch associated with art and even less with Art Basel, which they love to hate.

I could opt to not travel to the U.S. until Trump is out, or Turkey until Erdoğan is out, or Israel until Netanyahu is out. That's risky, but I still want to make the statement. I noticed that every time I post something critical of the Netanyahu administration, for example, I lose followers. But again, if you look at my tweets, it's not that I believe I harbour any truths, but I can spot good commentators and I try to highlight the good writers.

My greatest readership is in the U.S. and this is very influential because if you can get people to read what they wouldn't otherwise, then you become powerful. My Twitter feed is vital to my art presence. I share information on that platform in a way that is similar to how I share my collection.

I love to share knowledge. One of my dream professions was to become a teacher. That's why I enjoy it when schoolchildren visit the collection. They don't ask about the names of the artists—which is common practice in our elite art circles—they ask about the stories behind the works. That's what we do on the three floors, we tell stories, until you get to the top floor where the names are listed.

NKIt's well known that your daughters are not interested in the collection, so what is going to happen to it?

ASThe collection is a personal history. It's a journey from my schoolboy years to the time spent in a Wall Street suit, through to finding myself in Kochi and Jakarta, wondering what I was doing there. Perhaps I could document it in one way or another, but I have no intention of building a mausoleum, nor do I want to burden my daughters with my life. When I'm gone, either they'll take part of it, or sell it. As you might know, 25 percent of any collection is actually worth something. They'll recover some money and put the rest on the sidewalk. Hopefully someone will pick it up from there and enjoy it.

NKWhat are your ideas on fractional ownership?

ASIt's a huge rip-off. Theoretically, the idea is good in terms of giving access to others, but the problem is there are more crooks in the art world than in a drug market. It's so easy and tempting to cheat. I can advertise that there was a work by Anish Kapoor for USD $3 million, but I can also buy the same work at Christie's for USD $700,000. If you buy it, and sell shares for USD $3 million, you get an immediate profit of USD $2.3 million.

Then you put people in a situation of private equity or closed-end funds, where you don't allow the people to liquidate until you decide to. You get the fees every year for running it and when everyone dies of old age, you pocket the shares. You might create a secondary market to sell the shares, but it's the same as part-time sharing, and the scandal with timeshare apartments. Why would it be better with art ownership, when it is even more opaque? I just don't trust the intermediaries.

NKIn a way, shared property goes against the idea of exclusivity and scarcity.

ASThe sanctity of scarcity is actually the responsibility of the collectors and not the gallerists—a gallerist is nothing more than a garment retailer. The garment retailer will only sell what sells, so we cannot blame the gallery or the art fair, we should blame the collectors for this.

NKBut will collectors ever form a bloc?

ASNo, but we can hold a mirror to them and say: this is you. The problem is people don't want to see themselves.—[O]