Antony Gormley

Antony Gormley. Portrait: Emiliano Cribari

Antony Gormley. Portrait: Emiliano Cribari

One of the things that sculpture can do is remind us of the true richness, breadth and depth of embodied consciousness.

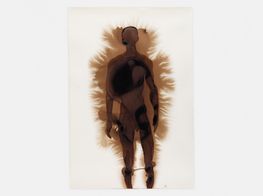

British artist Antony Gormley is widely acclaimed for his sculptures, installations and public artworks that examine the body and its relationship with the intimate darkness of subjective space and its objective counterpart, collective space. In 1995, Gormley created a seminal work entitled Critical Mass comprising 12 basic body postures—from the contemplative to the supplicant—each cast five times to produce a total number of 60 works that can exist in any orientation. Gormley describes the work as 'forensic evidence of a lived moment in time'.

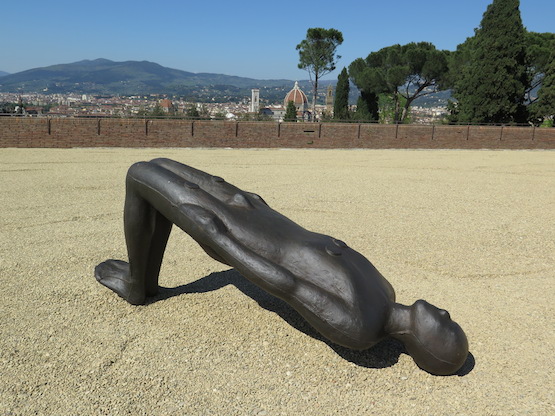

Critical Mass operates at the core of Gormley's largest exhibition of singular body forms, Human, which recently opened in Florence at the site of Forte di Belvedere. Situated on the lower terrace of the fortress and installed in a linear progression from foetal to stargazing, the 12 bodies of Critical Mass recall the progression of man. On the opposite western side of the lower terrace is a jumbled pile of the same bodies—an evocation of the victims of the 21st century. As Gormley states: 'This dialectic between aspirational and abject is the tension that runs throughout the exhibition'.

In this interview, Gormley discusses the original ideas behind Critical Mass, how the exhibition Human relates to its site, the idea of the collective subjective and what he views as the greatest challenge in relation to the architecture of the urban.

ADAt the core of the exhibition,Human will be two arrangements of Critical Mass, a seminal work from 1995. You once said in an interview: 'All of my work is performative in that it starts with an event.' Can you please expand on this, perhaps in the context of how you originally conceived of Critical Mass?

AGCrtitical Mass was an attempt to examine both the state of the body and sculpture. It was made as an account of moments of lived time at a point when I became fully committed to casting solid masses rather than making void works. The idea was to celebrate the fact we live in a time of mechanical reproduction and to destroy the idea of any uniqueness of a work but also to examine sculpture as object and sculpture as the potential location of feeling and the site of potential projection.

The making of the 12 forms was done very deliberately in a concentrated time in the spring and early summer of 1995. The bodyforms exemplify 12 basic body postures, all relatively symmetrical and all capable of being held for one to two hours whilst the moulding was made. What interested me was how the reading of these positions, once captured and turned into iron masses that are 10 times the specific gravity of a living body, might be changed through orientation. This is particularly true of the kneeling and mourning figures in the sequence. I was conscious when I made each of them that they would be displayed any way up and that in losing their original orientation, they would become abject or ironic in the process.

I think that the relationship between terror and beauty could be said to be the foundation of my response to the site and indeed a review of the whole notion of humanism.

The truth claim of the work is that it is the forensic evidence of a lived moment in time and I think of these works as industrial fossils or having a similar relationship to life as the figures cast from the vaporised bodies of Herculaneum and Pompeii. In many senses the subject of Critical Mass was a bearing witness to the victims of the twentieth century and conflating over-population, the state of the body and the proliferation of genocide particularly with the state of the sculpture of the body.

ADForte di Belvedere, the venue for the exhibition in Florence, historically functioned as a defensive fortress and an expression of temporal power. How do you view the exhibition's relationship to the site's historical function?

AGFerdinando di Medici finished building the fort in 1595 and there was no question that the Forte's primary aim was to make clear to the people of Florence who was in charge of the destiny of the city. It was never really considered as a defensive instrument against enemies from outside of the city. Its emblematic nature is a clear expression of the power of money to make both war and art, to inflict suffering as well as delight. I think that the relationship between terror and beauty could be said to be the foundation of my response to the site and indeed a review of the whole notion of humanism.

ADWhen you originally created Critical Mass, the work was intended as an anti-monument evoking the victims of the 20th century. In a city famous for its monuments representing the 'ideal man' by Renaissance artists such as Donatello and Michelangelo, does the idea of the 'anti-monument' become more potent?

AGMy works are absolutely sculpture, not statues. They are influenced by the process-based American work of 25 years ago, at which point materiality became more important than representation. I think the contrast between myself, Donatello and Michelangelo would be laughable if you were interested in the jobs that statues do: to idealise, to make images of heroes, to make convincing representations of power, to invite the public to emulate a moral example. In contrast, my work very evidently refuses to be representative and refuses to be a moral guide but absolutely insists on the centrality and importance of sculpture as a vehicle for feeling. Statues are often of victors but I am more interested in expressing our vulnerability and dependency not only on our fellows but on the natural systems of the planet.

There is no point in making art unless it becomes part of human experience and I absolutely believe that the subject of my work is the subject who witnesses it.

ADYou have said that your figures represent the collective subjective. Could you please expand on this in the context of the exhibition?

AGEach work is the registration of a moment of lived time of a particular body in a particular configuration and, therefore, is a celebration of the subjective position of all human beings and an example of our collective embodiment. It attempts to produce within the viewer an equally subjective projection or response. The sculptures come from a particular body that could be any body.

The displacement of the work provokes the question, 'What is this thing doing here?' and the work returns the question with 'And what are you doing here?' addressed to the viewer. In re-engaging with the body and with Critical Mass in particular, I have tried to evoke basic universal body positions in an attempt to expose an inherent lexicon of body postures. This is a re-calibration of the tension between the particular and general, the subjective and objective, the basis of individual experience and its potential to be shared. This is at the heart of my project.

ADWhat is your single most important concern in deciding how to place each form in an exhibition?

AGThe works work as a whole. Metonymy and holism depend on two things: firstly, that the work should resonate and act as acupuncture within the context, making the space alive. Secondly, the desire lines of the flow of the viewer's body through the Forte must be allowed to become meaningful. The memory of the last work the viewer sees qualifies the experience of the next. These sequences build upon one another from one to the many. There are places where you can see the whole layout and others where a sequence of works can be seen from a single viewpoint. The openness of the terraces has allowed me to make a show in which the encounter with particular works can contrast with a vision of large parts of the show laid out in front of you. There are tensions between darkness and light, open and closed, visible and hidden, that animate the whole. I have tried to use the tunnels, the loggias, the powder stores, the rooms of the Palazzino and gunpowder stores, each with their own unique level of natural light, carefully. Light is a principle material. Light and how you approach a sculpture becomes an important part of how the emotion the work demands is received.

ADOne of the works in the exhibition presents a body leaning against the wall in a tunnel, evoking a homeless person. Are you able to please discuss your specific intentions in making this figure and placing it?

AGCritical Mass is a phrase describing the necessary density of a nuclear isotope prior to fission taking place, but here I am using this idea to examine social fallout, to talk about the tension between high-density urban populations in the world and their vulnerability to human fission. Some people no longer have a secure place within the social matrix and in the last years we have become accustomed to seeing the homeless person sheltering in the front porch of the bank. It was important to me, in talking about the victims of the twentieth century, to include not just those who have lost their lives—the body as refuse—but those still living bodies that are seemingly unable to play a part within a constructive human life. I want to recognise and acknowledge their existence and to mark it.

ADThe body leaning against the wall also evokes the idea of the body and its relationship to architecture, a theme often explored in your work. What do you view as the greatest challenge in relation to the architecture of the urban?

AGWe have become used to two very pernicious forms of contemporary architectural practice. One is the exploitation of cities as an opportunity for capitalist investment where financial return is put above any sense of urbanism. Office and luxury home developments are proliferating in our city centres without any regard for the quality of life that they should support or extend. The second is architecture as icon. There is an increasing demand for cultural buildings that often fail abysmally to fulfil their function. The recent Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris is an example where architecture itself has become a form of expressionist sculpture that betrays all functional necessity.

The biggest challenge facing humankind is to develop cities capable of sustaining through smart technology and clean energy the populations that they house. More importantly they must necessarily provide the employment, education and health services that really improve and sustain human life at high density. It seems that insufficient creativity is being exercised in the evolution of our city centres. It is clear we can do so much more; we have never had access to more research or been better able to construct intelligent and life affirming habitats.

In contrast, my work very evidently refuses to be representative and refuses to be a moral guide but absolutely insists on the centrality and importance of sculpture as a vehicle for feeling.

ADOlafur Eliasson says of his work: 'I like to believe that the core element of my work lies in the experience of it.' To what extent could this statement be applied to you also? Does your work require a viewer to be activated?

AGThere is no point in making art unless it becomes part of human experience and I absolutely believe that the subject of my work is the subject who witnesses it. There is no intrinsic value in a work of art until it is experienced. The work of experiencing art in our day is as important as the work of the artist.

ADI imagine someone a thousand years from now coming across your forms and struggling to situate them as being from a particular century. In creating your work, do you ever think of how people might interact and perceive it in centuries to come?

AGMy work is immediately associable with industrial production and therefore with this Modern era. I think everything that is made has a conversation with everything that has already been made and to that degree my responsibility is to understand the continuity of the need human beings have felt to make a material account of their lives. My principle responsibility is to my own time even though I am aware that perhaps people who are not yet alive may understand my work better than I do myself.

ADIn an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist in 2007, you said the issue you found most problematic about your work was how to use material means to overcome the limitations of vision. Of all your exceptional projects, where do you feel you have come closest to achieving this?

AGI am aware how limited the visual world is and yet how central it is in the functioning of the brain. One of the things that sculpture can do is remind us of the true richness, breadth and depth of embodied consciousness. The body and mind are fundamentally linked, the two enriching the other. I am very aware of the limitations of the visual. I want to somehow reach beyond language, beyond the illusions of appearance, to levels of experience that are deep and perhaps are more felt than thought.

ADWhat next?

AGBack to the studio to continue evolving the two strands of the work: firstly, making true evocations of what it is to be alive and secondly, constructing instruments by which I and others can experience being alive in a self-reflexive way.———[O]