Baptist Coelho

Image: Baptist Coelho. Courtesy the artist.

Image: Baptist Coelho. Courtesy the artist.

The Siachen Glacier is the highest and coldest battlefield in the world; it is located at an average altitude of 20,000 feet in the disputed Kashmir region claimed by India and Pakistan. Both countries maintain permanent military personnel on the glacier at a height of over 6,000 metres.

With temperatures dipping to minus 60 degrees in the winter, every year more soldiers are killed because of severe weather than enemy firing. It is estimated that since 1984 around 4,000 soldiers have died as a result of the Siachen conflict. Almost all of the casualties on both sides have been due to extreme weather conditions.

Indian artist Baptist Coelho's work has to date been deeply influenced by his own curiosity and desire to understand the impact of the Siachen Glacier upon the soldiers who man the conflict zone it delineates. In researching the lives of these soldiers, Coelho has developed a poignant body of work that explores ideas of humanity, conflict, relationships, survival, and bravery. It builds on a practice that incorporates installation, video, sound, photography, found objects, site-specific works and public-art projects.

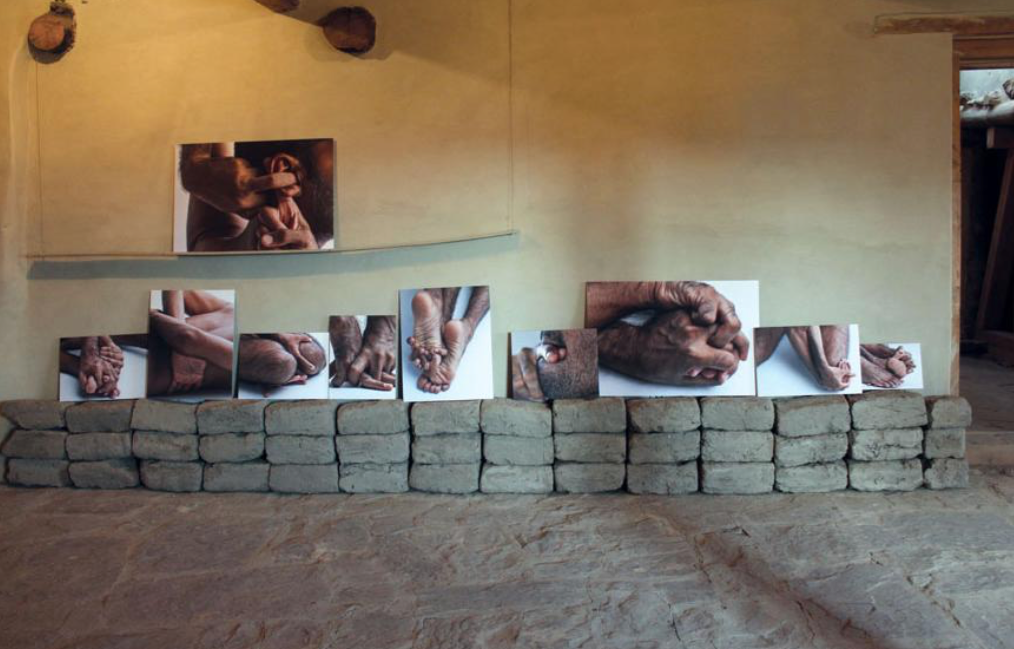

Earlier this year, Indian born Coelho was awarded the 12th annual Sovereign Asian Art Prize for his work, Attempts to Contain (2015). The work consists of eight photographs on archival paper which explore how the body responds to the psychological and physical need to protect itself by forming a mesh of interlocking body parts.

In this conversation the artist speaks about his background, his body of work focusing on the Siachen Glacier and in particular his recent award. He also discusses his residency at King's College London in the Department of War Studies, and touches on the work to be included in an upcoming exhibition, Traces of War (26 October–18 December 2016) at the Inigo Rooms, Somerset House East Wing, King's College London.

ADTell me a bit about your background. I understand you actually pursued a career as a graphic designer before becoming an artist?

BCI graduated in India as a graphic designer. As a child I was always interested in design and in advertising. There was a time in Indian television when the advertising was more interesting than the actual programmes on television. There were certain characters created to sell a product.

ADWere you interested in advertising's ability to communicate an idea, or were you interested in the actual visual experience of it?

BCI think it was both. The advertisements were well produced. They seemed more sophisticated than films. They were almost like a mini film, and the production was better.

An uncle of mine introduced me to commercial art and the study of visual communication. He showed me an example of neighbours who were doing it and introduced me to the idea of how my interest could be used in a profession.

ADHow long did you work as a graphic designer?

BCI think five to six years.

ADHow did you make the switch into fine art?

BCI was very interested in design, but my ideas were not seen as very practical. They were too obscure: 'The client won't get it. You cannot be too clever about'. So I was facing these issues.

I then got a scholarship to study at the Birmingham Institute of Art & Design in the UK. It was a very good institute.

ADWhat did you focus on there?

BCI focused on the idea of how to use air as a medium because I wanted a challenge and I wanted to work on something I had never done before. I wanted to look at how it was possible to make art out of air. This was in 2005-2006. I started looking at air in the body, air in the atmosphere, and at how artists were using negative space and making it positive. I was looking at artists like Rachel Whiteread in this respect.

My tutor was excellent. He could see there was a need for me to explore something beyond design. But at this time, I didn't imagine myself as being an artist. In India, being an artist means studying painting and drawing. And so I couldn't see myself as an artist as I had not studied these disciplines.

My tutor however could see that I was moving towards being an artist, rather than a designer. When I started putting my material together, he said: 'That's an installation'. He said to me, 'Edit it'.

ADTell me about what you created from your investigation of air while in Birmingham.

BCWell, I did this project whereby I collected bottles of air from around the world. In 2006, the bottles I collected became part of a solo exhibition I did at the university. So after my MA show, and having been exposed in the UK to all the different forms art can take (from the Slade shows to the RCA shows to the Tate Modern shows), I wanted to do another show.

My tutor and the university were supportive and they helped me put together a solo exhibition that very much came out of the projects I had been working on during my MA.

So I was this person who came to university to be a designer and I left wanting to be an artist. I still find it hard to digest that I can be an artist. It took me a long time to call myself an artist. I really didn't want to call myself an artist for such a long time. It is such a huge responsibility.

ADWhat was it that gave you the confidence to finally call yourself an artist?

BCThere wasn't really a drastic moment when I suddenly felt I had become an artist. But when I returned to India, I did receive an award called the 'Promising Artist Award' [awarded by Art India and India Habitat Centre, Delhi, India in 2007], and I suppose that helped.

There is a large body of work I have created which relates to the Siachen Glacier. The glacier and the work I have done in relation to it has very much influenced who I am as an artist, and it has shaped my focus.

I know it isn't possible that my artwork is going to have an impact, change the situation of conflict, or save a particular life from that conflict. But I want to bring into focus ideas of what it means to be a soldier, and what it means to be 'brave'.

ADCan you expand on this by describing how you work and the focus of your practice?

BCI have been looking at war and conflict and looking at different aspects of war and conflict—not just in India and Pakistan, but also around in different geographies, wherever I have travelled.

In 2006 when I came back to India there was a call for submissions to be made for something called 'The Peace Project', which was a project instigated by the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver (MCA Denver). They called for artists from around the world to respond with an artwork. And I was looking back at some ideas I had around the concept of bravery and being a soldier. I was interested in this idea of 'being brave'.

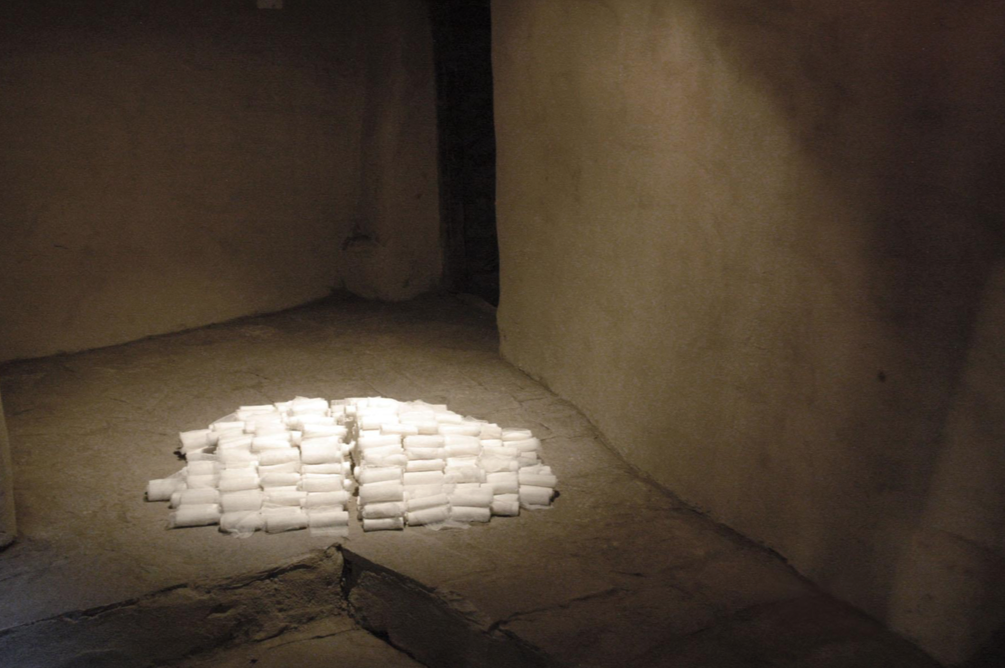

I also wanted to respond to the idea of conflict because I was living in Bombay, which is secure and safe. How one feels living there can be so distant from the sense of security people feel in other parts of the country or world. If you live on the border between Pakistan and India, then you are vulnerable to political conflict in a real way: to bombs and so on. Through Google I found a satellite view of the Siachen Glacier. I took that satellite image and converted it into a pile of gauze bandages. It is a three-dimensional form; I arranged the bandages so they reflected the satellite view. I was reflecting on this idea of healing; so many lives have been lost due to the conflict surrounding that territorial dispute. I was also interested in the distance from the reality of conflict that the satellite view provided.

As a former advertising person, I became very interested in people's responses to my work. I was interested in how an object I make can cause people to feel something about an issue. The work was selected by the museum for the Denver exhibition. It received a good response.

ADAnd from the work you created for the Denver exhibition, how did your broader practice develop?

BCI felt what I had done wasn't enough. I wanted to explore the ideas in the work further. I wanted to understand the conflict further. So I started going up to Ladakh, which is a region in the North of India, close to Pakistan. It is a mountainous region and close to the Himalayas and where the Dalai Lama has a house. I started going in 2008, and since then I have been every year to research for my artwork. It was very much about looking at how to get close to the glacier. Practically speaking I could get closer, but it is very difficult to get really close. So I went to the [Leh airport in Ladakh]: dramatic landscapes, really fantastic—imagine Tibet, Mongolia—that type of landscape. It is very breathtaking. It is tough to be there because it is backwards, natural toilets and so on. I was quite amazed. I had to acclimatise and I started to engage with the people there.

I went there and I spoke to various people, from officers and soldiers to mountaineers on the top. It made me realise how important interacting with people is for my work. Today, most of my work is based on conversations.

ADYou mention wanting to understand the conflict more. I understand this desire to be less about understanding the political issues relevant to the Siachen Glacier in favour of learning more about how the conflict surrounding that area impacts the individual, both physically and mentally.

BCYes, you are right. I was very interested in how the conflict impacts the individual, particularly the impact it has on the body. I found an image taken of soldiers on the glacier. It was an image of a soldier celebrating a birthday on the glacier. You can see a cake. I was intrigued by the image, it made the soldiers human beings and that image made me focus on the soldiers and their personal experience of being in that zone of conflict (rather than the political aspects of it). It was so important to me. I wanted to look at the personal and from this angle question the politics behind these men finding themselves as soldiers on this glacier.

It is quite complex being a soldier, because they are both protectors and attackers. And the lines become blurred. There are these different sides to soldiers and why an army exists.

I can only present certain stories. I don't take a view on it.

ADCan we discuss some of your earlier work in terms of exploring the physical impact that the conflict zone has on soldiers?

BCThere is an artwork I have done where I just focus on colour; you see the same white landscape the soldiers look at. You know soldiers spend a lot of time looking at food packaging, just so they can look at colour. Up there, they are surrounded by white all the time. They spend a lot of time looking at the text on packaging too, they memorise phone numbers, and shop addresses on the packages to keep themselves amused. There were so many stories I heard about soldiers and what they do. So my work is also about offering up an understanding of these men. Many felt they were born to 'protect', there were so many conversations where you had this sense of the soldier and his need to be 'heroic' and 'superman' like. And sometimes the discussion about the need to 'protect' and be 'heroic' is used to dodge the personal. So the 'not saying' becomes the 'saying'.

I know it isn't possible that my artwork is going to have an impact, change the situation of conflict, or save a particular life from that conflict. But I want to bring into focus ideas of what it means to be a soldier, and what it means to be 'brave'.

ADHave you shown the work you have created about the Siachen Glacier in the region?

BCI showed this body of work in Bombay and this woman, came up to me, and it turns out she had a space in the very region I was investigating. But, given the sensitivity of the area, it took a long time for the exhibition to happen. It didn't happen until 2015.

ADAnd what form did the exhibition take and what was the response to it?

BCThe art space is a 17th century restored house. It is a very beautiful place near the Leh Palace.

It was very interesting. The audience there are very shy. Many people came to see it. And many people, including soldiers, saw it and could see what I was doing. They could see I was talking about bravery, but some could also see I was critiquing that 'brave' work and questioning it. And others couldn't see that. I do respect the service these men give.

Many locals came to that exhibition and they were not the 'art crowd' at all. There were Buddhist monks, regular people.

I created a video in which there is an image of moving fingers. It is about a game you play as a child. I did this video to show how the body is connected and dis-connected. A little girl came up to me and she asked: 'Are you trying to say that soldiers are warming up their fingers by doing this action?' I said 'No, not at all'. And she went on, 'But there is a video where all the clothes are coming off the soldier'. That response to the work amazed me. And I thought, 'If she can see that video and bring so much meaning to that, I need to include it'. I was interested in the obscure and direct references people could make, because they know what the cold means to them.

ADYour artwork that won the Sovereign Art Prize, Attempts to Contain (2015), is very much related to how the body deals with the cold. Tell me about this work.

BCThis work is about how the body can create its own fabric.

The director of the artspace in Ladakh is an expert on Himalayan textiles. We got to know each other, and I was interested in fabric and I have used a lot of army textiles in my work, but I don't use them because they are beautiful or because of their particular aesthetic. I use them for conveying the idea of 'how to protect and survive'. During our collaborations and conversations, we thought 'let's produce a body of work that looks at fabric in the context of the Siachen conflict', so we made things like a parachute out of Tami wear. One of the conversations that came out of this process for me related to the question of, 'How does a body make its own fabric?' There was a video that I did in the past in which all of the clothes of the soldier automatically start coming off; it all opens magically, as if a ghost is opening and taking the clothes off. It is a very simple animation technique and it is a long video and finally the body of the soldier is seen—a naked body. You can see the skin of the particular person and it was the end of the video. I wanted to show a human body, one that is fragile and vulnerable. And when I was doing the fabric project I started thinking more about the naked body and what does it do to create its own fabric and protect itself. Can the body create its own way of covering itself? Not just physically, but mentally. When it is minus 60 degrees you experience hyperthermia/memory loss/hallucination. How does one protect oneself, even psychologically and mentally?

There are particular lines in fabric: the weft and the waft. I wondered if the body can create a weft and a waft, and from this idea I created hundreds of images of a body trying to entwine itself to create a mesh out of fabric.

When I first showed these works in a porter came up to me (the porters accompany the soldiers to the top of the glacier; they are not trained army personnel), and he said 'When the soldiers have chilblains, or frostbite, the hand movements reflected in your photos are what we tell them to do. It is part of the first aid we administer against the cold. When you are cold, you need to start putting parts of the body into the body's cavities to create heat'. I was fascinated by this connection. You know, if I had shown this work in Bombay people wouldn't have read that into the image. I realised I not only had to go to that place to make the work, I had to show it there to draw out that type of reaction.

ADYou have talked about a fascination with engaging audiences and their reaction. Is there not a curiosity to show this work on the other side of the border?

BCI wouldn't be able to do this. It would put the women and the organisation who showed my work in India in a difficult position. I have not shown these works in Pakistan or China. I would have loved to do the research from the other side. What would be interesting to hear is from people on opposing sides and to hear their views. But it is too much of a challenge. Just having the Pakistan visa would cause me so many issues.

ADAfter this project, what?

BCI also have some projects in London and in France. I was looking at the history of the military there. I have a large body of work in London. I am interested in war museums and how they bring forward the idea of war.

ADYou are currently participating in a residency at King's College London?

BCI am now in the midst of a residency at King's College in the Department of War Studies. Part of the research I am doing relates to the glacier pre 1984, before the conflict, because a lot of British explorers visited and explored that terrain in the late 19th century to early 20th century.

There are particular lines in fabric: the weft and the waft. I wondered if the body can create a weft and a waft, and from this idea I created hundreds of images of a body trying to entwine itself to create a mesh out of fabric.

ADSo you are exploring the glacier from a different perspective?

BCI am looking at it from the British explorers' perspective. I am very interested in how the glacier looked before it was a conflict zone. I spoke to a particular mountaineer who wanted a 'peace park' in the zone. Peace park means a neutral zone with no soldiers. To send a message of peace, he climbed a Swiss Alp along with a Pakistani in 2000. He said he wanted the glacier to return to its wild form.

I am looking at archival material in relation to the glacier. I have found that so many British explorers had been to the glacier and mapped the area. These maps were then strategically used.

I was doing a recent talk at King's College London, and I discussed my project of collecting air. I talked about how I took empty bottles and was stopping off at military bases in the region, and I would get asked about what I was doing, and I would explain that I am an artist and I am collecting air. People would laugh, but they helped fill the bottles. They would fill the bottle with air, and they also had to put a note in the bottle. They often wrote what was on their minds, and because the date and time are on each note, the bottles are like a type of time capsule. When you see these notes in totality, you can view the tensions of the landscape. If I had asked people directly, I don't think I would have received the same response.

But what was interesting is after I did my talk at King's College a member of the audience came up to me and she said: 'I am interested in what you said, because when British explorers went to explore there, they often went as 'artists''.

I am aware that these explorers were there mapping certain areas for strategic uses. When I look at the archive photos, what I see are beautiful black and white images of the landscape, but really they mean so much more.

In October there will be an exhibition in London and part of that research will be shown in that particular exhibition. —[O]

Baptist Coelho participates in 'Traces of War' (26 October–18 December 2016) at the Inigo Rooms, Somerset House East Wing, King's College London.