Ben Grosser Wants to Mess with Your Socials

Ben Grosser. Courtesy the artist.

Ben Grosser. Courtesy the artist.

Ben Grosser has spent much of the past decade developing guerrilla strategies for slaying the social media monsters that are consuming us.

A professor of new media art at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Grosser has designed software that strips away the number of followers and likes from Facebook and Instagram. He created low-EQ code that responds to your friends' posts with random emojis. And he's found a way to break the highly-touted TikTok algorithm.

Not easy to categorise, his creations have appeared at conferences and new media biennials going back to 2012, though more recently they've also shown at art institutions such as London's Barbican Centre, Berlin's Museum Kesselhaus, and Lisbon's Museu das Comunicações. Emblematic of the urgency of its themes, his work has been picked up by magazines and newspapers such as The New Yorker, Wired, The Atlantic, and The Guardian.

A survey of his efforts, entitled Software for Less, opened at London's arebyte Gallery on Thursday 19 August and continues until Saturday 23 October. The title is a rejection of Silicon Valley's obsession with growth, where more users and engagement leads to more venture capital and greater returns for investors, along with more surveillance, anxiety, and alienation from the offline world.

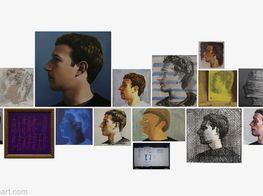

The exhibition is presented as a tech expo with the requisite swag—candy, stickers, T-shirts—to draw attendees to the 'products', each a different work. Two videos of Mark Zuckerberg play in the space. Order of Magnitude (2019) is a 47-minute supercut of all the times the Facebook CEO has publicly invoked different kinds of growth, while Deficit of Less (2021) scrapes together the few times he mentions declines. Deficit of Less amounts to barely a minute of video, but it's slowed down to match the duration of Order of Magnitude, rendering Zuckerberg's voice in a bass robotic drone.

The video installations at arebyte give coherence to a body of work that is mostly designed to be experienced on our laptops and smartphones. As part of Software for Less, the artist created his own social network called Minus (2021) where, instead of feeding an endless scroll-down of content to an insatiable audience, users are limited to just 100 posts. Instead of quantifying a user's followers, posts, and likes, Minus's only visible metric is the number of posts they have left.

SGMinus reminds me of Twitter. Limiting users to 140 characters changed the way people wrote online, a shift from longer, often self-indulgent blogs to punchlines and protest slogans. How do you see Minus changing the way people engage online?

BGTwitter's character limit had the primary effect of producing more posts. More posts inevitably provide more data which enable more algorithmic analyses and thus, new opportunities to transform human interaction into actionable profit-making.

Minus is an experiment to see what happens when the big social media model of more is turned on its head. We've come to think about big social networks as something we'll live with for the rest of our lives. When we walk around the world many of us can't help but see it in terms of its potential to become future (popular) Instagram posts or TikTok vids.

This way of thinking, of needing to forever manage our presentation of self within online corporate platforms, is very much to the benefit of those platforms. They are forever dependent on and enriched by our continued engagement. They engineer their systems to induce our production and participation in whatever way they can. More of us is what they need.

But what if a social media platform didn't need us all that much? What if we knew they weren't always going to be available?

I suspect we'll see a variety of approaches to Minus's 100-post limit. Some will likely hoard their cache of future visibility, whether because the limit makes those few opportunities feel weightier, or because they're so used to treating visible metrics as something to optimise that they'll want to keep their public 'post remaining' counts as high as they can.

I expect, and hope, that some others will see the site's radical constraint as an invitation to experiment. Maybe it will become a generator of online performance art, or a way of documenting a series of events, or maybe they'll just burn them all out in one fell swoop.

Part of me worries that the 100-post constraint will feel so limiting that most won't slow down enough to try it out at all. Though if that's the case, I'd also see it as reflective of the wider condition that big social media has produced. They've animated us into a hyper state of more where time is measured in 'seconds ago' and sociality is about how many or how much rather than who or what.

After a decade of work on the topic, I can confidently say that visible metrics make us compulsive, competitive, and anxious.

SGInstagram has experimented with removing metrics—they said to 'depressurise people's experience'—before ultimately leaving it up to users to decide. What sort of feedback have you gotten from users of your Demetricator (2012) works, which strip out the numbers?

BGWhen I originated the concept of social media 'demetrication' — a term I coined when I launched Facebook Demetricator in 2012 — I wasn't sure how it would play out. Most thought I was crazy or at least strange to hide the numbers which by that time had already become the primary way we navigated social media platforms.

By 2016, when Facebook legal first came after me for my efforts, I had heard from so many users of Demetricator from around the world that I'd already published a journal article sharing my findings and theories about the negative effects of visible quantifiers on social media.

After a decade of work on the topic, I can confidently say that visible metrics make us compulsive, competitive, and anxious. They change what we write and say online, and affect how we see ourselves and others.

Like counts, follower metrics, TikTok views, and all the rest teach us that quantification is the best way through which to measure our experience of and influence on the world. They reconfigure our sense of time in ways that make seconds or minutes ago seem old. In short, they change who we are and what we do, often without us realising this at all.

I see Instagram's efforts as highly disingenuous. After two years of experimenting with the idea (a veritable eternity in Silicon Valley time), they concluded by saying their research suggested that visible metrics aren't really all that influential, but that they'd be happy to give users the option to hide them if they want to. What Instagram actually provided, however, was the most convoluted and poorly designed method of metrics hiding I could have imagined.

Not only did Facebook come after me in 2016 for my Facebook Demetricator, Instagram came after me in 2020 for an Instagram version I'd built in 2018 (before they'd ever talked about the idea themselves). They don't really want to hide the metrics because metrics are, primarily, productive of engagement on their platforms. And more engagement is always what they want.

SGThe TikTok algorithm has been described as scarily insightful, serving people up very different content according to their use patterns. Your work Not For You (2020) attempts to befuddle algorithms by automating selections the user wouldn't ordinarily make. But don't people want to see content that caters to their personal obsessions and feel like they're part of a particular community?

BGThe TikTok 'For You' algorithm isn't nearly as effective as the mythology around it suggests. The real (evil) genius of the platform is the format, the structure, the interface design, and its foregrounding and amplification of its own brand of hypermetrics. The whole package is what keeps us scrolling.

Super short vids mean we never feel like we 'lost' much time watching a video we didn't like. The repetitive soundtracks burrow into our brains, making one more flip of the thumb to the next video feel like an easy, happy, almost instantly-nostalgic choice. The feed's lack of reliance on follower and following networks makes the achievement of stratospheric metrics seem like a strong possibility for anyone at any time, further encouraging production for the platform.

My own experience of the For You algorithm is that it's not that dissimilar from YouTube. If I watch a handful of cat videos on TikTok I start getting lots of cat videos on TikTok. I find it very easy to get stuck in ruts, and have found the algorithm extremely resistant to my feedback, repeatedly ignoring, for example, my 'not interested' messages on subjects it keeps trying to pitch me on.

One thing I saw over and over is that, no matter how often I or my software ignored influencer videos or liked videos from users with no following at all, TikTok just kept trying—relentlessly—to pitch me on its most popular stars. I saw this happen so often that I spent a few days with new and old accounts trying anything I could to stave off the influencer wave. I was never successful.

This mirrors information that's gotten leaked out of TikTok in the last year or two that revealed internal content moderator guidelines for the suppression of user content. The company directed its staff to downplay videos by 'ugly' people or old people or users in less-than-beautiful environments (e.g. if they had a 'crack' in the wall), or if their content was critical of TikTok itself.

We can't just accept these personalisation algorithms that presumably 'get' us and live in the world that they fashion for us. The big social platforms aren't there to inform, they are there to engage. So whatever they show us, its primary purpose is to keep us scrolling and liking and producing.

I argue we need tactics and strategies that confuse those systems and how they see us. Sure, doing so may mean we end up watching content that doesn't immediately go on our list of favourites sometimes. But when did we start thinking that the only content worth watching is that which we already like?

SGGo Rando (2017) does something similar to Not For You, but it messes not only with the algorithm, but with the user's social groups themselves by having a bot react to their friends' posts with random emojis. Have there been any calamitous consequences of a misplaced emoji?

BGI still find myself chuckling, years after I first released Go Rando, how even my friends can get upset or confused when I click a 'reaction' that doesn't report what they expect. I mean, I've used the Go Rando logo (an emoji mashup) as my avatar for years!

I think it's vital that at least some of us work from within.

Big tech has taught us that we should answer the questions that software asks, that their systems are disconnected from the ideologies of their creators. And so, when someone posts about a bad day and a Go Rando user incongruently reports that they're Haha about it, it can definitely produce a moment of friction.

But friction is productive of criticality and thus antithetical to the aims of Silicon Valley. Such friction thrusts into the limelight that a site like Facebook is asking us all to report how we feel all the time. And we feel compelled to be accurate in our reporting!

SGWhy not just log off all these sites?

BGIt seems like every few months #deletefacebook enjoys new temporary popularity. Lots of people talk about it. But few ever disconnect. Why? Well, for some, sites like Facebook or Twitter are practical if not literal job requirements. Try asking a major media journalist to stay off Twitter—it's just not a realistic option for most of them!

For many others, getting off social media means disconnecting from friends and family and opportunity. That's because as a public we've let private companies build private platforms that have become so dominant that they outcompete all other options. Facebook and the rest are now fundamental infrastructure, more important than the phone or the roads or the newspaper.

Some who critique the platforms do so from an outside position, untainted by any significant experience within. That's a valuable vantage point, and a strategy artists and scholars and critics have used for centuries. But I argue that a primary component of living in the 21st century is one's affective experience of being on the platforms.

They are designed to influence how we feel in order to change what we do and who we are. Therefore I think it's vital that at least some of us work from within. I live on the platforms just like the rest of us. I feel the pull of a like count and find myself checking my own or someone else's follower count. I use these moments as my guide for where to go next.

Because so few people are able to get off the platforms, it's important to use them as a vehicle for imagining alternatives. We need to start seeing these systems as opportunities for experimentation and manipulation, and to stop treating them purely as sites for consumption and prescribed interaction.

Just because a piece of software asks us to report how we feel, we're under no obligation to be accurate about it. Just because a site suggests it gets us—and makes us feel like it might be right—doesn't mean we should accept or even necessarily appreciate its algorithmic analysis.

There's not much of a market for art that antagonises big tech with free browser extensions and 50-minute Mark Zuckerberg supercuts.

So even though I've now started to build my own platforms as an additional way of imagining alternative software futures, I'll stay on and in the big tech machines for as long as everybody else does.

SGYour work feels intensely salient, but is it something the art market wants? Do NFTs offer genuine possibilities to you as an artist who codes his creations?

BGThere's not much of a market for art that antagonises big tech with free browser extensions and 50-minute Mark Zuckerberg supercuts. Though to be fair, it hasn't been a focus of mine. I most want my works free and out in the world for everyone to experience, and art collecting isn't generally in alignment with that goal.

Further, I'm so focused on the intersection of capitalism and software that I often end up making works that, by their very nature, aren't easily collectable.

I'm also someone who's been critical of the so-called 'crypto art' movement from the beginning. For years I've watched digital artists turn out important works into a space that was fairly disconnected from the conventional art market. And in my view, much of that work has been prescient when it comes to technology in important ways. I would argue that the relative lack of collector/commercial interest in digital art has been an important factor behind its criticality.

When NFTs came along, however, what I saw was so many digital artists on my feed toss that critical perspective out the window. Overnight, they transformed their previously strange or interesting or informative feeds into loud running advertisements, announcing every bid and every sale and endlessly hyping activity from crypto art platforms. They replaced their social media bio links—which used to point to their own websites—with links to their profiles on those platforms.

They started talking about themselves as crypto artists—a term I would presume means they make art about cryptocurrency but which almost always meant instead that they make art they sell for cryptocurrency. Since when did digital artists primarily identify themselves with the form of payment they're currently accepting?

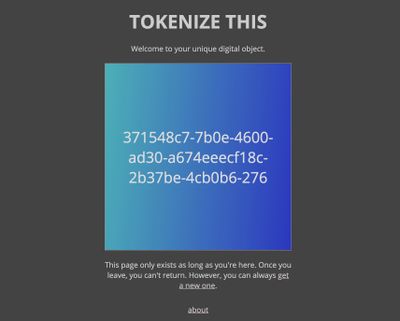

So my response last February was a work called Tokenize This (2021). It's a producer of 'unique digital objects' that can only be viewed once. Every visitor to the site gets one—and an associated URL for it—but subsequent visits to that URL return a 404 Not Found error. In other words, that new object is destroyed as soon as it's created.

It was my way of thinking about and resisting the capitalist ideologies embedded in NFTs and the ways in which crypto art markets have already thrust an often anti-capitalist and anti-corporate art medium into a 21st-century gold rush frenzy. —[O]