Bill Henson

Photo: Mark Ashkanasy Courtesy of Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Photo: Mark Ashkanasy Courtesy of Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Faced with the daunting, but intriguing challenge of interviewing one of Australia's most distinguished artists, Bill Henson, I did the contemporary obvious — I googled him. The result was, as one would expect, slightly polarized. His recent withdrawal of work from the Adelaide Biennale following a police complaint had reignited the debate that surrounded the new infamous incident, which resulted in a police raid of his 2008 Sydney exhibition at the Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery. Pre-dominantly and refreshingly however, a majority of the search results did not descend into unfounded moral hysteria, but focused on the artist's practice, and his poignant and thoughtful contribution to art, and particularly photography.

One of Australian's pre-eminent artists, Henson was launched into the spotlight in 1975 with his first exhibition being held at the National Gallery of Victoria — he was only 19. Twenty years later he represented Australia at the 46th Venice Biennale. His work is held in all major Australian collections including the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Art Gallery of South Australia, Art Gallery of Western Australia, National Gallery of Victoria and the National Gallery of Australia. Among international collections, his work is held in the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York; the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Denver Art Museum; the Houston Museum of Fine Art; 21C Museum, Louisville; the Montreal Museum of Fine Art; Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris; the DG Bank Collection in Frankfurt and the Sammlung Volpinum and the Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna. Major retrospectives of Henson's work at the Art Galleries of New South Wales and Victoria in 2005 attracted more than 115,000 people, and his work has also been studied widely in Australian schools for many years.

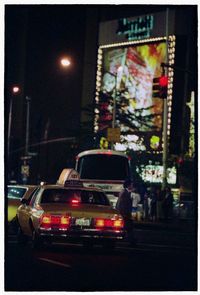

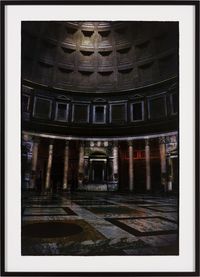

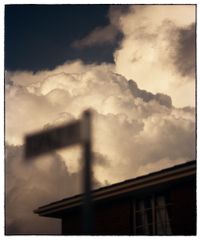

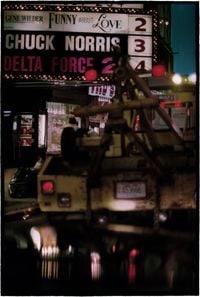

Tolarno Galleries in Melbourne recently opened an exhibition of Henson's photographs, Untitled 1985/1986. The exhibition presents a selection of work from a series of photographs that Henson did over twenty-five years ago; and are a reminder of the dedication with which he has used photography to explore the world, humanity and art throughout his career. The work represents a selection of images from his Suburban Series and in it we can see the familiar investigation of the smudged and blurred boundaries that exist between certainties — for example, literally in the shadow of both ascending and descending daylight and metaphorically in the moments between childhood and adulthood. Using more often shadow, rather then light, to create uncertainties and complexities within each image, Henson has created a photographic monument to the ordinary beauty of suburban life.

In the wake of that opening and as a two part series, I spoke to the artist about his practice and career. In Part One, the artist talks about his first exhibition, and his practice and approach to photography generally. In Part Two, Henson addresses a number of issues, including the status of a photograph, his interest in both lighting and curating his exhibitions, and his anti-portrait of Cate Blanchett. The artist also took the opportunity to provide a considered response to the recent controversy that again surrounded his practice following his decision to withdraw his work from the Adelaide Biennale.

ADYour first ever exhibition was quite phenomenal in that it was at the National Gallery of Victoria — and you were only 19. Tell me about how that exhibition came about?

BHI was still at art school — at Prahran College, here in Melbourne. I had a number of wonderful teachers — in particular two great photographers by the names of John Cato and Athol Smith. Despite the fact that I never attended class, they were long suffering supporters of mine. Every couple of months I would walk into class with a bundle of things I had been working on under my arm — none of which were related to the assignments that they had set. It was a three-year degree, but shortly into the second year they took me aside and said: "Look we think you should go away and do your own work". However, in the process of them looking at the pictures that I would bring in, Athol Smith, unbeknownst to me, showed them to the curator of the National Gallery of Victoria. The Board and the Curator decided they wanted to do an exhibition. Athol walked into class one day and announced it to the class. I was as surprised as anyone else.

ADTell me about the images that you showed in that exhibition?

BHThe pictures I had been making at the time dated from about 1974 and the show was in 1975. The images were all of ballet students. Although I was interested in depicting the dancers, they were just a part of it. What really preoccupied me was the space they were working in. They were working in an old dance hall from the turn of the century and the light coming into the rooms really struck me. There was white paint on the windows, so the light was very diffused. And I remember just walking into this space - I have always been strongly effected by light - and I was just dumbstruck by this light and the sense of strangeness in this room. I spent about a year or so taking the pictures. When I think about the pictures they really were about the light.

ADIt seems to me that your work is very much concerned with the study of light. How else would you describe your work?

BHI think you can very quickly descend into the clichés — most of which are true of course when you talk about these things.

My work is very much about the suggestive potential of the medium. It's about opening up a space into which one's imagination can flow: 'What is going on? What is the nature of this situation? Who are these people, when is this, where is this?'

I've always thought of photography as the most profoundly contradictory of mediums and perhaps that's why I'm still making photographs rather than making things out of clay or whatever else. Photography does have this kind of evidential authority, which is at the centre of it. And yet - after that sort of dumb literalness, that sort of veracity - it still comes back to what the medium can suggest, rather than prescribe. You have this kind of ringing proof of something, but the thing is that you have to lightly step right over that to something else, that which is indescribable. And of course the capacity to describe the indescribable is when all of this becomes interesting.

I often use the shadows or the absence of light to reintroduce some uncertainty, some mechanism that causes us to wonder. Often it's what goes missing in the shadows or how you make a seemingly pedestrian or mundane object strange again - whether it's a cup and saucer on a table, a thunderstorm in a forest, or anything else. It's what causes you to wonder — that's which I am fascinated by.

ADWhen I look at your work, it often seems to me to be investigating the undefined moment that exists between certainties: that moment when day becomes night, a child becomes a teenager or a teenager an adult.

BHYes. There's all that stuff about Cartier-Bresson's 'decisive moment', but I'm more interested in the indecisive moment. I am interested in exploring something that's both there but slipping away from thought at the same time.

ADYou originally began exploring art as a painter. Have you ever thought about returning to that medium?

BHI painted and did it compulsively throughout childhood and made things out of clay. I was always making things. For me now it just happens to be what I am making is photographs — they are simply a means to an end. They could be something else. This is not to make light of an utter dependency and love of working with a particular medium. Nevertheless, there's a sense that if you could draw closer to this thing, that's powerfully apprehended but not fully understood, using a different medium, then you'd use it. You'd stop making photographs and start building things out of wood or whatever else.

ADThere is a fair amount written about the relationship between your photographs and painting. I was reminded of Vermeer when looking at some of your works.

BHI would start by saying that the last thing I am interested in is making art about art. So there is no conscious or deliberate intention on my part to make some kind of quotation or critical reflection on other pictures from other times. That said of course, we are entirely inside our time and place, and always influenced by the things around us. I am very interested in pictures and sculpture and so forth, so those things inevitably go into the soup and are mixed around. But I am certainly not out there trying to in some way formally comment on other works of art. I think art about art is pretty trivial. Art about love and death, vulnerability and growing old, and desire, is much more interesting. So those things in a funny kind of way are accidental - inevitable, but accidental.

ADIs there a particular way you hope your works will be read?

BHIt comes back to the priority of individual experience. I sometimes say to my students that there is a picture of mine of a road winding off into a dark forest — the thing is I've made the picture, but if it absorbs your attention, it effectively becomes your road. And this is the great thing about art generally - and not just photography in particular - there is no correct way of listening to Mozart or looking at Rembrandt, there's only your way. It can be informed by knowledge and experience but it's still that solitary journey that we all go on, and hopefully it's an interesting one.