Biraaj Dodiya and Udit Bhambri on Collecting, Making, and Seeing Art

In Partnership With Vadehra Art Gallery

Courtesy Udit Bhambri and Biraaj Dodiya.

Courtesy Udit Bhambri and Biraaj Dodiya.

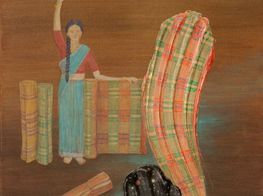

Set amongst mediums including drawing, graphite and collage, ceramics, and hand-embroidery by Faiza Butt, Ruby Christi, Anoli Perera, and Rakhi Peswani, to name a few, Biraaj Dodiya's five paintings in the group exhibition (ME)(MORY) (20 January–24 February 2021) contribute to a reflection on the processes of identity and experience construction curated by Dipti Anand.

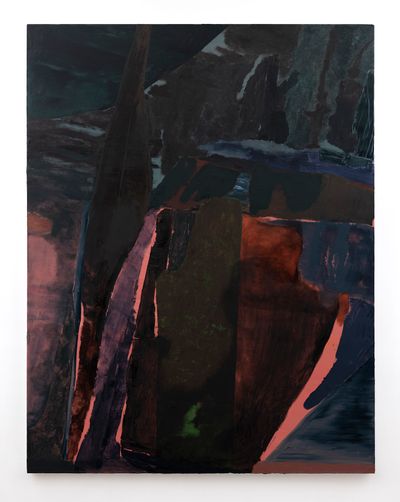

Using bold brushwork and deep sensitivity in paintings rendered with a darker palette, Dodiya invokes the feeling of 'moving through a familiar space in darkness'. That dead-of-the-night stillness is felt in paintings such as Twin Falls (2020), where two emerald streams tumble from a dark cliff face into teel-blue waters. Her inclusion in (ME)(MORY) marks the first time the artist has shown her work at the New Delhi-based gallery.

Working primarily in painting and sculpture, Dodiya received her BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2015, followed by an MFA from New York University in 2018. A recipient of the 2022 Civitella Ranieri Visual Arts Fellowship, the artist's first solo exhibition was Burn Your Finger, and Kiss it Yourself at 80WSE in New York in 2018. Interspersed in the space were a series of sculptures referencing urban structures, with materials ranging from cement, rubber, wood, polyurethane, bicycle chains, a harmonica, a bicycle tube, and more.

Such structures came in contact with Dodiya's paintings in Stone is a Forehead, her solo exhibition at Experimenter's Hindustan Road space in Kolkata (6 March–30 June 2020). Referencing loss and growth, the exhibition was presented like an excavation site, with plank-like sculptures propped up against walls, their rectangular forms mirrored in the paintings, whose dark planes are gently interrupted by vibrant hues.

Biraaj Dodiya's practice has caught the attention of gallerists and collectors in recent years, including Mumbai-based Udit Bhambri, who joined the artist for an online talk on their approaches to perceiving art, held during the course of (ME)(MORY). Bhambri's personal collection contains artworks by M.F. Husain, Akbar Padamsee, Sudhir Patwardhan, Nilima Sheikh, Nalini Malani, N.S. Harsha, and Atul and Anju Dodiya. It extends beyond a collection of artworks, Bhambri explains, to stories, learnings, memories, and experiences with galleries, artists, and collectors.

Bhambri shares some of these experiences with Dodiya in the following transcript of their talk, moderated by Vadehra Art Gallery Director Roshini Vadehra, and the two consider the different ways that art can be approached and appreciated.

RVUdit, I'd love to start with you. Have there been any moments that defined your journey with art?

UBI don't know if it's one single point that really defined where the journey began. But in the summer of 2019, I visited the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and I encountered Dance at Bougival by Renoir (1883). I recalled we had a print of the painting at home, and I remember spending hours in front of it.

Seeing it, I realised the reproduction could have been the starting point of something. I think it really defined how I started viewing art. Back then, I didn't know the value of the original or who painted it. There were prints of these works everywhere and I reflected on this when I saw the original for the first time last year.

What about you Biraaj? Is there something that you can put a finger on?

BDSince we're talking today about looking at art, I should first say that it's such a privilege. Especially in our country, where beyond the basic necessities, it's so hard sometimes to access art and to travel to see it. So I feel really lucky.

Looking at art started very young for me because my parents are artists, and they would take me everywhere if they could; to shows and openings in Mumbai, and then if they were travelling.

The more you look, the more you start to find what you respond to.

One of the first moments that I remember very clearly feeling something was when I was six years old and my parents had taken me with them to Italy. We went to Arezzo to see Piero della Francesca's frescoes, and then we also went to see the Uffizi. There was restoration going on at a lot of these places, because work had been damaged in floods. It was being restored with the same amount of care and importance as my grandmother was giving her small temple at home.

I think that's the first time that I connected the idea of this complete devotion and art together. That was what changed my view.

A second instance was at the Guggenheim, where I saw Matthew Barney: The Cremaster Cycle (21 February–11 June 2003). I don't know if it was for kids at all, but my parents still took me. I found my diary page from then, where I wrote, 'It's a very weird exhibition'. But for the first time, I saw the complete wildness, freedom, and madness that an artist was allowed to have, and the fiction and frenzied nature of it was like, 'Oh, you're allowed to do this, and this can be art'.

Now when I look back at it, I also understand that Matthew Barney, a white male artist, has a different relationship with freedom, but it really stayed with me, that feeling of, 'Wow, you can do this in the studio, and it's allowed.'

RVBiraaj mentioned that she went to a museum with her parents when she was six, and Udit, you must have done the same. I think we all have grown up with the privilege of looking at art with senior artists.

UBBiraaj, I think in some way you and I connected thanks to our parents having that same fan following for Prabhakar Barwe.

Prabhakar Barwe wrote this very beautiful letter to me explaining a work that's in my collection, called The Postcard (1993), and at the end of it, he writes, 'I don't usually explain my work because the creative process is so complicated. It discourages a viewer to understand it at first glance. It slowly unravels itself to the patient eye of the inner mind.' And that happens with so many works.

Roshni and I saw a David Hockney show together at the Tate a few years ago and obviously I was amazed to see paintings like The Splash (1967). And as we went on to the last room, there came the iPad works. I was very quick to judge and say, 'This doesn't move me' or 'This is not serious'. And who am I to say that? This person is using technology to make something so new.

It only struck me in March last year when the lockdown happened and the pandemic hit us, when Hockney created this simple iPad work of yellow daffodils that were so beautifully titled 'Do remember they can't cancel spring'.

It made me think that I totally shortchanged my own experience by rushing to the gift shop and buying what I already knew. I think art has that ability to unravel itself slowly. And that happens when you see Barwe's work. People may like or dislike it, say it's architectural, or this or that, but really, the meaning of it slowly unravels itself.

RVUdit, you've had a close relationship with M.F. Husain and Barwe. We discussed the experience of looking at exhibitions, and the connection that you feel to a work of art when looking at it with others in a museum, and I thought it would be interesting to touch on that again.

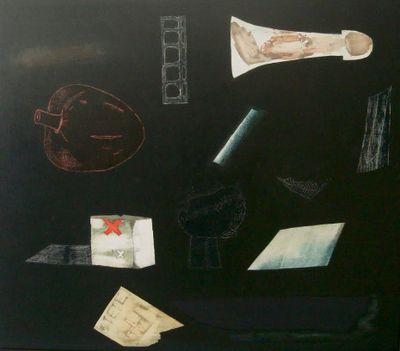

UBI'll very quickly talk about the Barwe story. The painting titled The Ruthless Prayer (1992) was based on the Bombay bomb blasts. This canvas depicts different floating objects—a building, leaf, something like a ticket ballot box, or broken glass. These were things I was trying to rationalise when I saw the painting.

There's this loudspeaker at the top of the painting—it's got blood smeared on it and as an eight year old, it never struck me until I was maybe 28 years old, when visitors unanimously noticed and mentioned that it looks phallic. I never thought of that, but when you understand what inspired Barwe, including Tantra, it makes sense that this work would unravel itself over time.

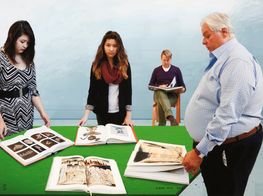

Going back to your question about museums, I personally find it fascinating to go beyond the artwork to observe people's interactions, and how one work can connect strangers. Two people may be thinking completely different things, but for that moment, the work is what's binding them together.

BDSomething that I also instantly question is how an artwork is made. What was the physical relationship of the artist with this? How much of their arm was moving? Or, how much of their body was changing this object that is now hanging in front of us? While making work, I also think about how the physicality affects and transforms the way I paint or make a mark or think of forms.

UBBiraaj, do you feel any kind of devotion to your canvases when you're working on them? You spoke about devotional paintings—is your process devotional or does it change over time?

BDI don't know if I can speak about my relationship with painting. But I do think that being in the studio every day working on something is a kind of devotional, monk-like activity.

UBI don't know if this ever has crossed your mind, but I've always wondered what the paintings think of us, as we dismiss, critique, or appreciate them in the museum.

If I'm looking at a work with my mother, and she's shorter than I am, I wonder whether she is getting the same view as I'm getting. That sometimes brings me to conversations around how the work is hung, or how something small is so intimate that you can actually pick it up and view it intimately.

BDNo, not exactly. I don't feel that way. But I do think that when I'm looking at somebody else's work, I'm going in with a certain response or a certain part of my own imagination that I'm applying to it, and the artist already has something that they're giving me and then that creates something new, and I'm more interested in that.

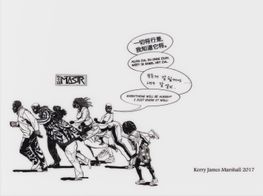

When I was living in Chicago, I saw an exhibition of Kerry James Marshall for the first time. After that, I felt as if I started seeing the world—every corner and every street—through his eyes.

Similarly, I'm so grateful that before lockdown happened, we had this amazing Sudhir Patwardhan show in Mumbai at the National Gallery of Modern Art. Once you see that work, you can't help but see the way he composes paintings and start seeing that in the city.

I was thinking about that show and his work a lot during the lockdown, because there's the exterior life, the Bombay city scenes—people on streets or in traffic or at work, when one remembers him, but also families at home, in rooms, or in smaller spaces together, which is how the last year has been for all of us.

I was also thinking about N.S. Harsha's work—images of people lined up, which for a while, we might not see. This idea of crowds has now changed. Earlier in the lockdown, workers were migrating across India. The idea of people in lines has now completely changed in my head.

RVUdit, I'd love for you to share a little bit about how you start seeing the world differently through stories you've heard artists tell.

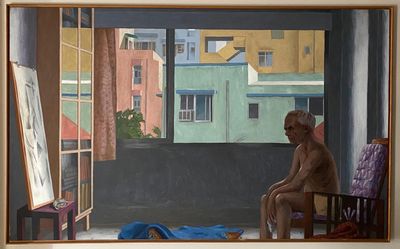

UBThis is a work by Sudhir Patwardhan called The Abstractionist (2005) that I've lived with a lot through the lockdown and I've spoken about it so many times, because I'm so fond of it.

I found it fascinating when Sudhir said that the buildings outside are forming these reflections on the glass paneling of the cupboard, making these abstract forms in the painting. Those reflections are a gift for being attentive. In personal conversations with Sudhir, he mentioned that it reminds him of Richard Diebenkorn—a lesser-known American abstract painter.

BDI like what you said about the reflection in the window as a gift for being attentive. That's really nice. When I was putting images together for this talk, I was thinking about how paintings of the city inform how you see it. That is the kind of the joy and the pleasure of looking: where you start to find moments or things from the world that are in the paintings, and things in the paintings that are in the world. This happens to me with abstraction also.

UBIt goes back to that familiarity, and what an artist brings to a painting. And then someone else is trying to decipher all sorts of things about it. Then the work has a life of its own as soon as it's left the studio, which is what makes it special and gives it its own journey.

That is the kind of the joy and the pleasure of looking: where you start to find moments or things from the world that are in the paintings, and things in the paintings that are in the world.

RVBiraaj, you've mainly been exploring abstract imagery in your own work. Is there a difference in the way you respond to figurative versus abstract when you're looking at other artists' works?

BDI love looking at both figurative and abstract painting. Of course, this idea of narrative and fiction becomes more active when you're looking at figurative work. But the things that ultimately make something good for me, I don't think that they have to do with whether a work is figurative or abstract. I think it revolves around the system and the language that is built. Also, when you see the artists working and failing and figuring something out—I find myself interested in that.

RVWe were talking about process the other day, and how even masters experience doubt and contemplation in the process of making art.

BDSometimes, you almost don't want to know too much about an artist, because then the personality and all this other stuff that may not matter in the work comes into play. I do watch a lot of interviews on YouTube about artists, and I find it very comforting when I discover that people who've been working for decades—someone like Richter, for example, who is considered very, very important in painting—still have doubt or hesitations when alone in the studio.

I guess this is also in letters that artists have written. I find that very important and helpful and reassuring that it's a natural part of the work.

RVDo you want to talk a little bit about your conversations with artists and how they've influenced your views of life and your surroundings?

UBAnju Dodiya almost got me arrested once, when I was in Rome. I had a very tight trip with three really close friends, and they were getting a bit annoyed with me because I was like, 'We have to go to this museum; now we have to go to that museum; now to see this.' And they were like, 'Okay, when are we going to eat? When are we going to do other things or just enjoy Rome?' To which I said we didn't have time—Florence was planned only for a day, so I could see very specific works.

So I'm putting up pictures on Instagram and suddenly Anju sends me a text message saying, 'Oh, you're in Rome, you should go to the Giorgio de Chirico Museum'. This was a Monday—I left my hotel premises and I went to the museum, and obviously, it was closed.

I couldn't find anyone there and I was so desperate. I started looking in itineraries to see how or what flight I could change to try and catch this museum first thing in the morning and then go, because it's not one of those listed museums. So I have to admit that I managed to convince the guard to let me in.

BDIt was just you alone in there?

UBJust me.

BDThat reminds me of something—last year, my parents and I went to Naples for the first time. We were all very excited because it has a lot of the frescoes from Pompeii. We were really excited about the Archeological Museum and several people told us that the metro stations there have works by contemporary artists—William Kentridge has a huge mural.

We thought, of course, we have to go, so we bought tickets, and then we saw an older woman swipe the ticket a certain way, and we just followed her and took the train. We get there, really excited. We're going up the escalator and there were four ticket checkers, and I guess the ticket hadn't been swiped.

There was a long back and forth. My dad was like, 'Three of us are artists; this is an important artist we have to see!' Trying to explain to this person that it's important for us to see this, but they just didn't care and then there was a fine. We had to go to the post office to pay the fine, my dad and I. It wasn't as planned as yours.

I personally find it fascinating to go beyond the artwork to observe people's interactions, and how one work can connect strangers. Two people may be thinking completely different things, but for that moment, the work is what's binding them together.

UBMine wasn't planned—that was one crazy moment where your mind makes you do naughty things when you really want to see art.

RVSo when you both go to museums while you're travelling, do you try and see every single thing and make sure that you don't miss anything? Or do you go with an agenda?

UBNot for me, not really. I like the feeling of being in a museum, so sometimes I just go. I very rarely carry a map or a floor plan to see the works. I feel like most things you can't plan; things just happen. I like to chance upon certain works.

BDI like to see everything. I'm very systematic about it usually, when I'm by myself.

RVLooking at public art, how does that change your experience? Udit, you have a good story about how you chanced upon an amazing public art sculpture and how that changed your perception.

UBWhen I was in San Sebastian, I happened upon a sculpture called The Comb of the Wind (1977) by Eduardo Chillida. I had never heard of him—it completely blew me away. The scale of it in the middle of these rocks in the ocean—the water was interacting with it and the iron was rusting.

I got Instagram messages saying there's a sculpture park by Chillida in San Sebastian. Friends were sending messages who knew. I didn't even know they were interested in art necessarily, and they knew about Chillida, so I was like, 'Okay, am I like completely clueless!' I didn't have the time to go to the sculpture park.

Then we were at the Hauser & Wirth booth at Masterpiece in London in June 2019. There were these two little works that looked similar to Comb of the Wind, and I instantly recognised them. Everybody around me was wondering how I knew about Chillida.

Sometimes people ask me, 'What's the one work you would want to have?' I'm actually happy to not have works that I encounter in museums and have everyone view them together with me. But I think sculpture by Chillida is something that I really aspire to have.

RVBiraaj, if there was one work that you could have, what would it be?

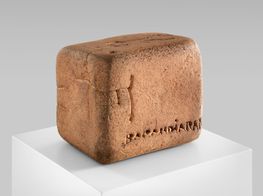

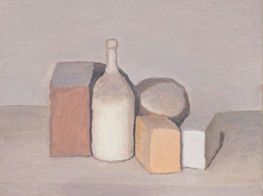

BDI think if I could only have one, I would keep it humble and get a small Morandi painting. Or I would get Brancusi's Endless Column and I would get rid of my roof. And then it could just be me and the endless column. Or I would get one of David Hammons' 'Rock Heads', which I think are really brilliant, or I would get the whole MET, and then Udit can come visit.

RVThose are really interesting choices. There's a question from our friend, Sean: Biraaj, I'm fascinated with your choice of a dark palette in your oils and acrylics. I was wondering where that stems from?

BDInitially, when I started making these paintings, I was thinking about moving through a familiar space in darkness. Say, when you wake up in the middle of the night—that kind of movement.

Also, there's a history of nocturnal landscape painting that I'm quite interested in looking at, and also night scenes in miniature paintings. All those things have kind of entered the work.

The honest answer is also that I make one and I keep building on it. That's very much part of the process. And that's how my thinking happens—that one thing leads to the other; one work solves problems or brings up new problems. That's how I'm working at the moment.

RVThanks Biraaj. Sean is also asking Udit, how do you respond to this dark palette in a contemporary sense, given your fondness for the masters and the moderns?

UBI don't think I respond to the palette; it's more the form or a thought. Sean's not wrong to ask me that question, because I tend to like a more monochromatic, darker palette. In fact, friends laugh and some of them say they will be thrown out of the house if they wear red when they visit, because it doesn't match everything else that's around. But I'm slowly moving to a more colourful palette.

Even in Biraaj's new works in the show, I found these oranges and purples. I don't know if it's got to do with the pandemic, but I think I'm veering a little bit more towards colour. Whether it's Arpita Singh or Nalini Malini or N.S. Harsha, I'm looking for that kind of brightness and colour. It really depends on the work, but I get where Sean's coming from.

RVOkay, a question from Sanjay. Biraaj, is there a certain consciousness, queasiness, excitement, intimidation, or pressure about being a daughter of artist parents? Do you share your work in progress with them? Or do you prefer to work in isolation until your work is finished?

BDI sometimes share my work with them while I'm in the middle of something. Not really when it's in mega action work mode, but closer to the end. In this last year, my studio has been in the same building as my father. Sometimes I ask him to come, but we never go to each other's studios without permission.

RVDo you feel any pressure or anything?

BDUm, no. I mean, I respect the work that they've done, and I feel like there's a lot to learn from it, and to do my own thing also. I think it's super important to acknowledge what they've done. Also, that I wouldn't think the way I do or look at the world the way I do if they weren't in my life, so I acknowledge that and then I have to do my own thing.

RVI agree. Udit, how do you go about selecting artists in your roster?

UBIt's easier for me, because I'm already working off a collection. So I'm either filling gaps or looking at what I don't have. I'm looking at different kinds of art that respond to some of the older art in the collection.

I'm interested in the possibility of conversations that the older modern masters are having with more contemporary art, and how they speak to each other. Even as a collection, it's important to infuse an older collection with newer art—it keeps it interesting; makes it more alive. So that's what I'm looking at.

To be very honest, also; a lot of the art that one looks at is not always in your budget. So that's sometimes a big constraint. Sometimes you stretch yourself. That's one of the criteria: you have to let go of certain things that you can't get.

When you're buying a certain work, you have to keep in mind that you're putting in a lot of money. I'm sorry to sound commercial, but you're putting money into an investment. You want to be careful that the work is going to go somewhere in the future. So there is a little bit of rationalisation that comes in; it's not as pure as just loving a work. That's unfortunately not enough, in my case.

RVThat makes sense. Biraaj, maybe you can address this: How does one learn to start seeing art more intently or more purposefully?

BDI think just from looking. The more you look, the more you start to find what you respond to. That's how I feel.

I find that one shouldn't have any pressure of trying to understand what the thesis is, and what the big explanation behind something is. Trying to see and respond to it intuitively is helpful for me.—[O]