Brent Harris on The Other Side

In Partnership with Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

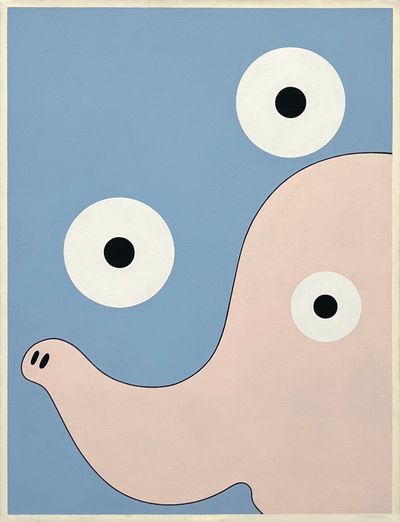

Exhibition view: Brent Harris: The Other Side, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki (6 May–17 September 2023). Courtesy Auckland Art Gallery.

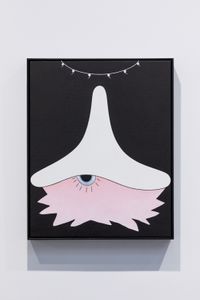

Exhibition view: Brent Harris: The Other Side, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki (6 May–17 September 2023). Courtesy Auckland Art Gallery.

Regarded as one of Australia's leading artists, Brent Harris's career and audiences have largely been centred in that country. However, following the death of his father in 2016, the artist consciously re-engaged with Aotearoa / New Zealand, the country of his birth, resulting in a rich period of artistic production and the presentation of the first comprehensive overview of his work at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Brent Harris: The Other Side (6 May–17 September 2023) takes its title from a suite of prints by the artist in the collection of Auckland Art Gallery, and alludes to the unconscious realm, the world of dreams, and that which cannot be rationalised but rather intuited: concepts that have sustained the artist over his lengthy career and which continue to be a driving force in his art.

Renowned for a distinctive body of works including paintings, prints, and drawings that drift between abstraction and figuration and which speak to conditions of the contemporary human experience, the exhibition covers an art practice spanning four-decades, from his earliest geometric abstractions made during the AIDS crisis in the late 1980s, for which he gained critical attention as a young artist, his psychologically charged paintings of the 1990s that are distinguished by pristine uninflected surfaces and sensuous organic forms, and his more recent large-scale canvases that draw upon wide-ranging art historical references as well as memories associated with his formative years in Aotearoa/ New Zealand.

Guest curated by Jane Devery for Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, the works included in the exhibition highlight not only the artist's reconnection with New Zealand, but the recurring themes that have come to define Harris's practice. These include a search for the self and one's identity as an artist; the psychological tension that can arise from childhood and family traumas; spirituality and religion; and the potential for art to convey heightened emotional states and address universal, existential questions.

In this interview with Jane Devery, who is also Senior Curator of Exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Harris discusses art practice through works that address universal themes such as intimacy, desire, spirituality, sexuality, and mortality.1

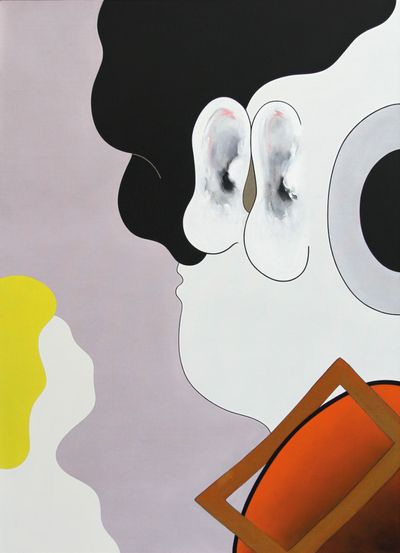

JDLet's start with the 2018 painting Listener. It's an important work as it dates from the time when you returned to Aotearoa after an absence of more than two decades. Like this exhibition, it signals a kind of homecoming and re-engagement with the place of your birth. Why did you first leave Aotearoa?

BHI moved to Melbourne in 1981 to study and got into the Victorian College of the Arts, for a three-year Bachelor of Fine Arts, in 1982. I was also putting distance between my past life in Palmerston North. I was married at 19 and divorced at 22. I came out as a gay man and moved to Auckland for three years before moving to Melbourne. I was also distancing myself from a domineering father who created a very complex family life. I had not spoken to him or seen him or my mother for the last 25 years of his life.

Listener is pretty much a self-portrait, or family portrait. The large figure heading off to the right represents the self. Within the dark hair, a profile is forming: this indicates my dead father, now only present in my head. He is looking down at the mother in the lower left. She remains sightless and mute. The two large ears represent my eagerness to hear something from either of them as I head back to New Zealand with a painting stretcher over my shoulder.

JDEven though your career has largely taken place in Australia, there were a number of early experiences you had as a young man in Aotearoa that influenced your development as an artist. Seeing the exhibition McCahon 'Religious' Works 1946–1952, a touring show that started at the Manawatu Art Gallery in 1975 in your hometown of Palmerston North, for example. What was it about this encounter with the work of Colin McCahon that made an impact on you?

BHI got married in 1975. I knew I was gay but never thought I could live a life as such. The exhibition of McCahon's religious paintings really affected me. The way he presented religious stories seemed very personal. I was so full of questions and doubt, guilt and shame. I felt I was identifying with McCahon's own questioning and his seemingly endless search for redemption. I felt he was seeking redemption for us all but as I have matured, I believe his mission was personal.

Religious storytelling is still a very active narrative in my work, and my own attempt at understanding and dealing with human frustrations.

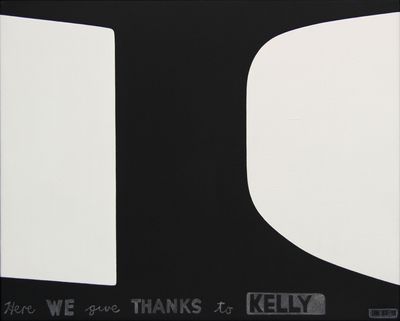

JDTraces of McCahon can clearly be seen in some of the earliest of your works in the exhibition, dating from the late 1980s. So can the influence of American artists such as Ellsworth Kelly, Jasper Johns and Barnett Newman. This was a time when you were working through influences and testing various strategies as a way of forging your own visual language. How do you see this stage in your career from the standpoint of 2023?

BHPost-art school, McCahon was the hurdle. I often returned to McCahon's painting Here I give thanks to Mondrian, 1961 (in the collection of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki). It's one of the few occasions McCahon acknowledges his debt to another artist. There are two paintings in my exhibition that directly name other artists' influence: Here we give thanks to Kelly, 1988, a work based on an Ellsworth Kelly drawing; and Painting Spot (Here we give thanks to Kelley), 1993 – Mike Kelley in this case. As a visual artist I live in a world of pictures, my own and others.

JDLet's talk about the title of the exhibition, The Other Side, which is taken from a series of prints, also in the Gallery's collection. They contain cartoon-like figures set against ambiguous forms that can be read as metaphors for the unknown, alluding to a space beyond reality as we know it. It strikes me that this is a kind of psychological landscape that your art often occupies. How did this imagery come about?

BHThe Other Side, 2017 series of prints is based on monotypes I had been working on since 2012. The technique used is called 'dark field' and starts with a printing plate completely rolled in black ink and as you start wiping away the ink, the image appears as light areas. I began with no imagery in mind, just smudging away and following what may come to the surface.

I was seeing a psychologist at the time, and he introduced me to the work of American psychologist Kurt Wolff and his idea of putting oneself in a position of surrender and then a preparedness to catch possible outcomes. My shrink likened this to my way of working from a blank starting point and remaining open to possible emerging imagery, almost as a form of automatic writing, accessing the subconscious.

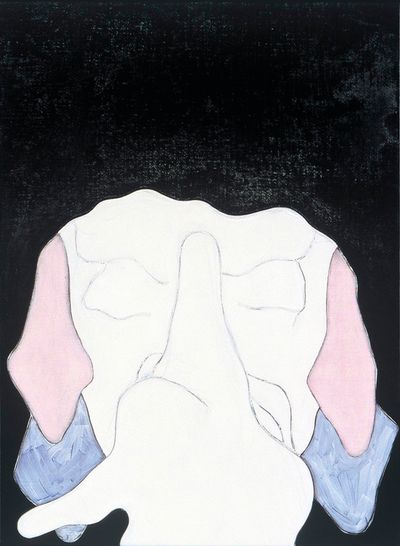

JDIt seems to me that accessing the subconscious realm is a significant motivator for you as an artist. In some cases, it also becomes the subject of your work. In the exhibition, this is perhaps most clearly manifest in works such as The Dreamer (2014), as well as earlier smaller paintings such as Sleep no. 7 (Silence) (2003). Would you say that being in a state of unknowing, or surrender, to use Wolff's term, is a necessary condition for you as an artist?

BHYes. The Dreamer is a painting that formed unconsciously during its process of making, with no preconceived meaning. There is a figure seen in outline, lying across the bottom on the canvas, perhaps recalling Goya's print The Sleep of Reason (c.1799), imaging the mind's veiled contents. Sleep is a series of 20 small paintings from 2003. We close our eyes but there is still a visual realm operating.

Around this time, I had contemplated painting a portrait of a rather important Australian art world figure and I suggested painting him with his eyes closed. This was met with firm resistance, as if it implied he had poor vision. He was in fact a character of enormous inner vision that he projected onto the Australian art world with lasting impression. My Sleep series refers to this. Even with our eyes closed in sleep we are often still inundated with visual overload.

JDThe way that your art addresses themes of family, sexuality and the subconscious realm suggests an affinity with the work of the great 20th-century American artist Louise Bourgeois. Certainly, you both have a shared interest in psychological dimensions of the human condition. I understand you once met her.

BHYes, I met Louise Bourgeois in 1989 at her house in Chelsea in New York. Her assistant Jerry Gorovoy took me there. She was quite fiery, launching attacks on a few other artists. Louise Nevelson and Cy Twombly were in her sights on that particular day. In hindsight you could perhaps see it as a performance, but there was a lot of energy there and I think this kind of energy was used as a generator for her work. The main attraction for me to her work was, and still is, her ability to visualise psychological states.

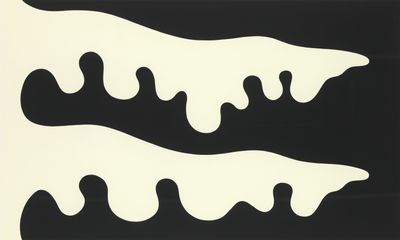

JDEdvard Munch, whose works similarly convey intense emotions, has been another important influence. Your painting To the Forest (No. 7 Small), 1998 for example, pays homage to Edvard Munch's 1915 woodblock print Towards the forest II (Mot skogen II). Can you describe your attraction to Munch and also the particular relationship between his brooding image and your painting?

BHThe psychological impact of Munch's print comes from the movement of two figures moving into the forest. Over time it has represented different meanings for me. The overwhelming reference in relation to my painting To the Forest (No. 7 Small), is found at the upper horizon in Munch's image— the descending slippage about to swamp the scene. My painting takes this slippage back to nature in the form of a snow-covered bow of a fir tree. My reading of the Munch print now is that this couple is moving toward death, the forest representing a return to nature, the earth. The comfort in the image is that they are supporting each other.

JDTo the Forest (No. 7 Small) is a good example of the painting style for which you became renowned in the 1990s. Pristine uninflected surfaces, organic shapes and stark contrasts between black and white (and later colour) were a way for you to convey both bodily and psychological states. How did you arrive at this distinctive visual language?

BHThrough my engagement with other artists. You know, it's a pretty long list, including Gordon Walters and Myron Stout, a little-known American artist who once said of his paintings, 'the source of the curve—of circularity—is in one's body'. The American artist John Wesley was another. His way of depicting cartoon imagery, where space and form are flattened out, really appealed to me, with its bald, no bullshit, no light source, no modelling. It carries something of Matisse's flattened interlocking areas, taken to a Pop extreme. I have still thought it possible to inject this non-emotive way of painting with emotive subject matter.

JDYour interest in the body and its vulnerability is apparent in some of the earliest works in the exhibition that relate your experience as a young gay man. Could you recount some of the episodes that inform some of these works? I'm thinking in particular of your experience living through the AIDS crisis and how that informed your series 'The Stations of the Cross' (1989).

BHI have never really identified as a gay artist. I have lived in fairly tolerant countries and times. But the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and 1990s was a terrifying and sad time for most gay people. I was not involved in political activism around the AIDS crisis but was very active in care teams early on when things were at their worst.

Around this time, I made my first series of The Stations of the Cross, and I approached the subject as a readymade narrative for a young person going to an early death: judged this morning, dead this afternoon. An older person going toward death is starting to tire of the body – you know things are starting to break down—but the speed with which AIDS reduced young bodies was alarming.

JDAnother work, the painting Apron of abuse (1992), similarly references a personal experience of being a young gay man. Could you describe the episode that precipitated this work?

BHIn 1992, as I was walking down Brunswick Street in the Melbourne inner-city suburb of Fitzroy, a man coming toward me spat out his abuse, calling me a 'fucking pansy', a term which is sort of redundant these days. I was into the German artist Sigmar Polke's work at the time and his Large Cloth of Abuse, 1968 came to mind—a large four-metre square cloth scrawled with apparently filthy abusive text. I remember having seen a photograph of Polke wearing his cloth, almost as a protective garment. If he is embracing the abuse and claiming it, those directing abuse at him are rendered rather superfluous.

At the time, I was also obsessed with the work of the American artist Robert Gober and a work of his came to mind, Slip covered armchair, 1986 which contains a painted pansy. I decided to address my own moment of applied abuse through a work. I domesticated Polke's large cloth into an apron, and added a fringe of pansies stolen from Gober, with a nod to McCahon in attaching my title almost as a label—the apron being a garment to shield against dirt.

JDOne of the distinguishing features of your approach is the way that you employ humour and embrace absurdity in your art, even when addressing difficult ideas. There was a period in the 1990s, following the six months you spent in Paris as artist in residence at the Cite internationale des arts, that marked a turning point when you allowed the 'absurd' to enter your work as a 'legitimate' subject matter. Could you describe this moment?

BHMy time in Paris was great. I was quite irritated by the good taste on display everywhere, including in most art galleries. I was working on a series of my own refined abstract drawings at the time when a ridiculous elephant head with trunk suggested itself to me. Such animal figuration would normally have been banished. I decided to accept this visual insult as my 'appalling moment' when I allowed this image to remain and become the subject of a number of works. For me, the Appalling Moment series was about the difficulty of expressing or describing a troubled human subjectivity.

JDFinally, the idea of searching for the self is a constant theme that runs throughout the exhibition and which you have returned to time and again over your entire career. My sense is that this is connected to your preoccupation with mortality and the quest to find meaning in life generally. Would you agree that this existential search is a driving force in your art?

BHYes, I suspect most artists are in search of their own mark. No matter how the work presents itself – abstract, figurative, conceptual, sculptural, post this or pre that, whatever – the artist is generally working from their present position in time. How does the work fit into the world now? How is it present? How does it relate to history? Is it making history? Oddly, time seems to sort art out. There are lots of misfits in human history who fit, in time. —[O]