Brook Andrew Reflects on 'This Year'

In Collaboration With Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery

Brook Andrew. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Dianna Snape.

Brook Andrew. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Dianna Snape.

For over 25 years, Brook Andrew has developed an extensive archive of vernacular objects and printed matter in his Melbourne studio, which he draws together in collages, sculptures, and museum interventions as a means of shedding light on neglected narratives.

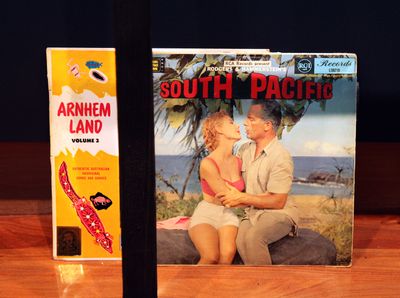

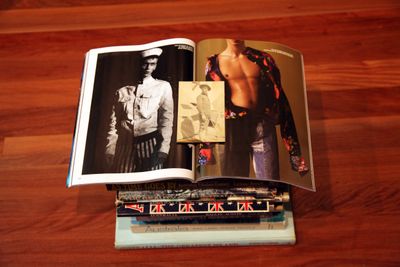

These archives have been collected from different places, whether from contemporaries like Marcia Langton, whose collection of past editions of The Saturday Paper Andrew took in; gathered from museums during residencies, such as the 1951 book Orixás by Pierre Verger, which the library of the Musée d'ethnographie de Genève was going to throw out, or rare postcards purchased from international auction houses.

Andrew also recalls receiving the archive of an academic who was retiring, whom he met during his Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship in Washington D.C. 'It's definitely become a kind of depository for these very different forms—sometimes glass slides, sometimes old film', Andrew notes of his studio, a refurbished factory.

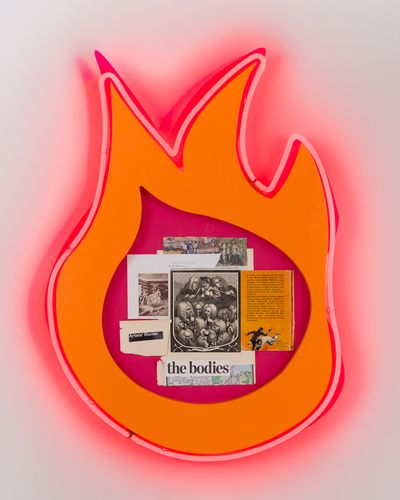

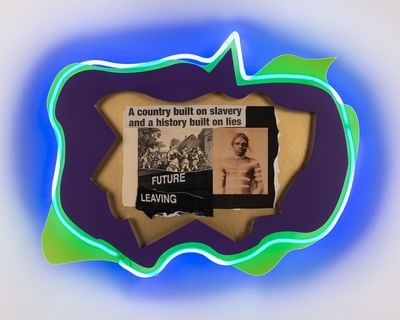

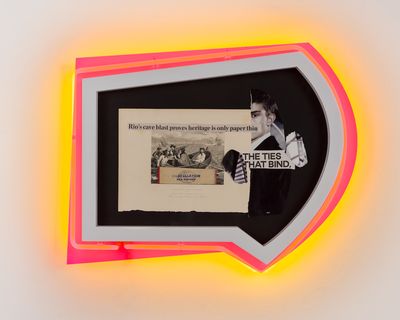

At Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery in Sydney, the artist's exhibition This Year (25 September–24 October 2020) drew from this archive, pulling disparate elements—from ethnographic materials, comics, rare books, contemporary newspapers, and fashion magazines—into powerful collages. These works, which are rendered sculptural through neon and metallic frames, or printed as large-scale immersive photographs, continue Andrew's probing of systems of power, revealing alternative narratives through playful presentations.

What are the stories that we own, what stories do we inherit, and also, what stories are kept from us or kept from other people?

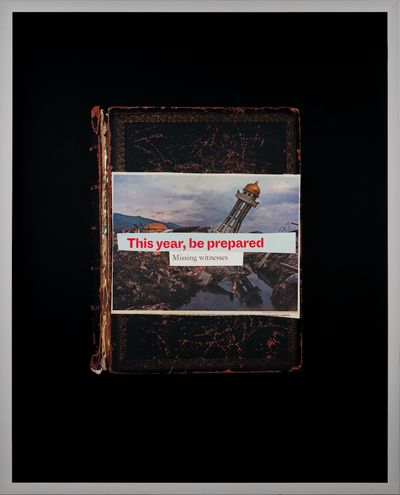

The show's title departs from a newspaper headline that responded to the climate catastrophe and the events of 2019, 'This year, be prepared', which could not have predicted the events of 2020. Quickly and frantically cutting and pasting various sources together, Andrew assembled elements varying from historical to popular culture, reflecting on the ways in which narratives are told by different media.

This is exemplified in the work This year, missing witness... (2020)—a large-scale metallic photograph of an original collage, that combines imagery from The New York Times newspaper along with the newspaper headlines cut from The Saturday Paper. The image of the destroyed temple is from the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, which has experienced increased natural disasters that many claim are directly related to climate change.

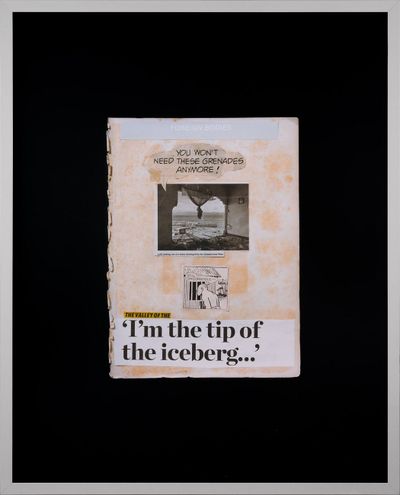

An image of a destroyed home in Sulawesi reappears in This year, still unconscious... (2020), also rendered as a luscious, larger-than-life metallic photograph consisting of further source materials, including images from original edition of engravings of the complete works of 19th-century British satirist William Hogarth. Andrew collected this book in Oxford, U.K., where he is completing a PhD on the power of objects in museum collections and the influence of satire on this process, and the engravings are present in collages throughout the exhibition.

It is important for Andrew's practice to include elements of printed matter that are often invisible, and which give the power of a newly created message. Hence, the moulded paper from Hogarth in This year, still unconscious... is juxtaposed with elements from late 20th-century Phantom magazines, including the cut-out of a man saying, 'still unconscious', taken from a magazine that was gifted to the artist's archive by a friend who collected the comic as a teenager.

Andrew is interested in the representation of colonised peoples in popular cultural forms such as Phantom. This includes gender and inter-cultural politics, and questions surrounding our responsibilities to those legacies in popular Western society and entertainment.

At the bottom of This year, still unconscious..., an excerpt of a news headline reads, 'I'm the tip of the iceberg....' With the iceberg referring to the tip of many urgent issues today in an increasingly connected international society, this piece reveals a question of some urgency: are we still unconscious about looking at the tip of the iceberg?

In this conversation, which is an edited transcription from a talk hosted by Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Andrew—who recently led the 22nd Biennale of Sydney (14 March–4 October 2020) as the Biennale's first Aboriginal artistic director—joins Artspace Sydney's executive director Alexie Glass-Kantor to trace his career as an artist, and the importance of community and healing in his practice.

AGKYour practice converges and juxtaposes the anthropological, the historical, and popular culture to rethink existing systems and structures of power and to playfully, satirically, and provocatively rethink what power looks like—who has permission to speak, and what representation looks like. Is that fair to say?

BAIt's also about what has been taken away from some of us and what we are fed, how we learn to be part of a dominant narrative.

Growing up with an Aboriginal mother and father of Celtic and Jewish ancestry, I always was interested in why my mum's family or my life, the experience of that identity, was not more in the public arena, especially in education. I felt like there was this disenfranchisement. I don't think that's changed much within popular culture to tell the truth.

Just look at Lidia Thorpe, the Greens Senator in Australia who is an Aboriginal woman of the Gunnai-Gunditjmara peoples. She was sworn into parliament the other day. When that happened on Twitter Live, there were quite racist and ignorant remarks towards her.

I am interested in challenging the narratives around what sovereignty means for Indigenous peoples, and other alternative narratives, not just around Indigeneity. What are the stories that we own, what stories do we inherit, and also, what stories are kept from us or kept from other people?

AGKYou've been working with archives since the 1990s, and recently you said something to me that was really interesting, that at some point you realised you were going to have to make your own archive if you were going to make the work that you wanted to make.

BAWhen I was at art school, 1991 was my first year, and I remember being at a thrift store in Western Sydney, and there was a ceramic Aboriginal head, what we call kitsch, and artists such as Destiny Deacon and Tony Albert and I started collecting them. For me it was this thing that I needed to get out of the public eye. Some of them were not very beautiful, but it was really the act of collecting them.

My Aboriginal grandparents had Aboriginal spoons with heads on them. It really depends on whose home you're in and what it actually means for you. When it was in the public arena it became too public, so it needed to be taken out and recontextualised.

Some of the things I've collected are really precious, like there's an Aboriginal breastplate, which was not cheap. They're so highly sought after, yet they hold such devastating histories. There are a lot of private collections in museums that have them, but there was an opportunity to acquire one and I built it within a sculpture for an exhibition called Sanctuary: Tombs of the outcasts, at the Ian Potter Museum of Art, The University of Melbourne in 2015.

How is it that we can look at such difficult narratives and histories, but also in ways that are informative?

I was working with Kelly Gellatly there, and there was a way in which that precious object that hung around an Aboriginal Elder's neck, but that then could be positioned in a way that spoke to that history, was very powerful. The same with looking at the human remains trade. How is it that we can look at such difficult narratives and histories, but also in ways that are informative?

AGKI think it's that living quality for you as a collector—you're not a trophy hunter, it's not the colonial paradigm of collecting in order to canonise a vernacular vocabulary or timeline. The way you collect is much more about unpacking the contradictions that can exist in an archive or collection.

BAAbsolutely. Early on in my career, back in 1996, I was associated with Boomalli, an Aboriginal artist cooperative; it was very formative years, it was very important. Hetti Perkins and Brenda L Croft were there, r e a was there, many other artists were there, and it was very important to have that sense of community around those ideas.

My first overseas intervention was at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter, and they informed me, which was a very surprising thing even back then in the mid-1990s, that they had repatriated all of their Aboriginal human remains. However, I discovered one skull in their collections, and the way I came across it was in a book of mammals.

People have to understand that Aboriginal people were collected like animals, and they were actually registered in the 'mammals' book, alongside whales, monkeys, and so on. But the other side to that is what is historical record? What is the truth?

In Australia, there are wars over histories—the black arm band versus the white blindfold views. But the legacies of these pasts goes beyond the historical records. There is intergenerational trauma. There shouldn't be a debate around that. And that doesn't just go for Australia, but internationally.

One interesting thing about that work in Exeter, coming back to this point about collecting, is that I could borrow the original Captain Cook journal log or ship log, to be in this installation, but they wouldn't allow me to move other objects around.

I was 26—I went out and got lots of Mills & Boon books, because it's fictionalised romanticism, and I ripped them all up, hundreds of them, and I scattered them around. People were a bit offended, because I was basically saying there was a fictitious romance around Captain Cook, which of course we know that narrative now and how those stories play out and the tensions around that.

Then I really started collecting a lot more, because it was about the narratives and the stories that I felt needed to be juxtaposed next to other histories in the world to get a more balanced view. Even within This Year, it's about bringing many different archives together, creating my own narratives, which I think is a bit of a parody.

AGKTalk us through the process of creating the works in This Year. Collage is such a radical form, and it has such a strong political history, too.

BAThey're things that I'm interested in. In the show, there are bits from everywhere; an auction magazine from Berlin, a cut-out from the front of a magazine that I got from the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies—and images of a terracotta figure from a book on Bali that I got in Geneva.

It was really just about a combination of how to create possibilities, and how to connect, as well. Not only shining light on shadow areas, but also things that are connected and questioning their historical relationships. For me, it's also about secret codes, because people out there will see different things, and that's really important.

The kid looking over with the neon light that goes up to the camera in This year, raking over... (2020)—for me, that's about photography, the gaze, ethnography, and the documentation of Aboriginal people.

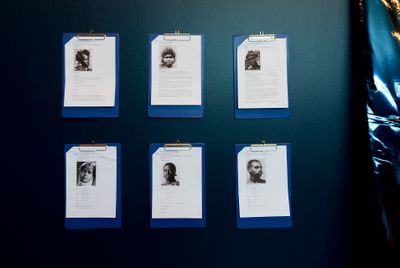

Some of the works also have original 19th- and 20th-century photographs from my collection. So, they're not just magazines that I've collected—some of them are highly sought-after photographs from auction houses. It's really important to include them as part of a comment on the international culture of collection.

One of my favourite works is This year, the bench.... The image of the judges in that one is a Hogarth.

AGKA book of engravings by William Hogarth appears beneath the image of This year, missing witness... (2020), and every one of the collages and images in this show has a piece of that original rare book embedded into it. It becomes a very strange, mutated DNA that sits within the exoskeleton of these collages.

What did you want to do with this show when you were thinking about that convergence of the collages, their shapeshifting into expanded, sculptural forms, and their relation to the architecture?

BAIt was completely chaotic, cutting and putting things together. The frames are like sculptures—they're containers for the collages. I worked with Mark Chapman to create them.

When I was putting the collages in the frames, I kept adding pieces. I had my archive with me and I was adding pieces to them as the last lid went on and the neon was turned on. The same with some of the larger mixed-media works—I was getting them digitised and then screen-printed, work with Spacecraft Studio and Negative Press. Then I'd bring them into the studio, and then sometimes they would just end up being different things. The action really dictated the final works.

For me, it's also about secret codes, because people out there will see different things, and that's really important.

Coming off the back of NIRIN, the 22nd Biennale of Sydney, where I worked with lots of artists, I wanted to create and transform the white gallery space into something that really reflected a kind of a journey or a different narrative or something that really subverted what is reality, because our realities are what we think our consciousness speaks to, when in actual fact, I think we're all in our own little spaceships sometimes.

AGKYou talk about the painted decal on the wall as a twist in a ribbon, or a kind of slip in the time-space continuum—almost bringing together a kind of vertigo. And when you come up the stairs and see these angles in the wall paintings, you really do get this sense of that non-linearity and that collusion of popular culture, history, and the present moment, which come together in a very powerful way.

BAWe're all walking vessels, and we have these different images and things in us. With the shifting of architecture through those wall paintings, and the blown-up collages that present reconstructed narratives and stories, there is the sense you could kind of fall into them.

I remember speaking with Roslyn, when the works were first going up, especially the photographic works, and sometimes they made sense and sometimes they didn't. And sometimes the narrative comes to you and sometimes it shifts, depending on how you are feeling or what you are doing or thinking at the time. I really like this open-ended engagement—it's not so fixed, and I think that's the wonderful thing about creating fiction, out of so-called 'fact'.

AGKI think these are really important works for collectors and institutions to think about collecting themselves, because they hold original material that has value within a larger vocabulary of thinking through the archive that stretches time into conversation and collision with other forms of representation.

BAThese sculptures are really quite dynamic and some of them are quite thick, and they're layered and layered and layered. There is a sculptural materiality to them. The work This year, cancellation... is really important because it talks about Rio Tinto's recent destruction of very important and ancient Aboriginal heritage.

The reference to 'cancellation' is from a stamp on a book that was decommissioned by the National Library of Australia—it was about race, colour, and colony, I think. It links to an idea of collection and what gets protection. Also in that work is an image from the Hogarth book of original engravings of people whispering together; conspiring. The work presents a very complicated, poignant narrative for me.

AGKSomething that maybe not a lot of people know is that you begin by drawing space and ideas, and then you translate them. That process of transformation, of form and ideas, is a really important one. You don't work to venerate objects in terms of the integrity of their original form, instead you're working to scaffold the ideas.

BAMy PhD thesis is on the power of objects, with reference to objects in museum collections, and understanding that for many Indigenous people, or people who hold objects sacred, the object has agency. This has pushed me further, because it's a tricky line to walk sometimes. It's not just collecting as a colonial legacy.

Take the work Horizon Line II, which was recently shown at the Musée du quai branly – Jacques Chirac. It's first iteration was created for RMIT Design Hub in 2015. For Horizon Line II, I worked with the curator Christine Barthe, with the Musée du Quai Branly collections and my own film archive.

The neon horizon line which cuts across the archival footage in the work references the landscape of Cowra at the Erambie Mission where my grandmother grew up and where my mum's family went fruit-picking when they were kids.

In this work I cut up the film footage, like a method of collage similar to how I worked with the book of engravings by Hogarth. I got into the habit of ripping that book up and using elements from that as really powerful moments. For me, it comes down to this concept of balancing the narratives of the world. How do we put light onto the shadow areas that are often suppressed and pushed into the darkness?

AGKArtspace commissioned you to be part of 52 Artists 52 Actions, where we commission an artist each week to do a project on our Instagram and online programme. We were working with you as a venue and partner for the Sydney Biennale at the time.

During that week, we saw people doing things like blacking out their Instagram, creating an erasure of images in the public domain in order to stand in solidarity, and there was a kind of impotency that we felt as an institution, sitting in our lockdowns, to create something meaningful.

We asked you to lead, because we thought the artist should lead, and we decided to let the work speak for itself, because we actually work with artists all the time to lead and rethink structure and power as a way that institutions can change through time.

BAThis was a very complicated week; this was when Black Lives Matter exploded in the United States. You and I and the team talked about what this meant, and we asked what the hell is going on, and what is this work saying. That was a really important time that also influenced this work.

Linda Burney, who is an extraordinary Aboriginal woman and politician, talked about how the BLM movement was so important for Indigenous Australians with regards to shining a light again on the deaths in custody issue.

It's just unfathomable that nothing has shifted with Aboriginal deaths in custody, even though there was the Royal Commission investigating these deaths, which came out in 1991. Since then, there have been at least 434 deaths of Aboriginal people whilst in the custody of police or prisons, and not one conviction. I included this newspaper headline about Linda in this collage, This year, missing witness... (2020). It also reflects on different places in the world—Indonesia, and many other places.

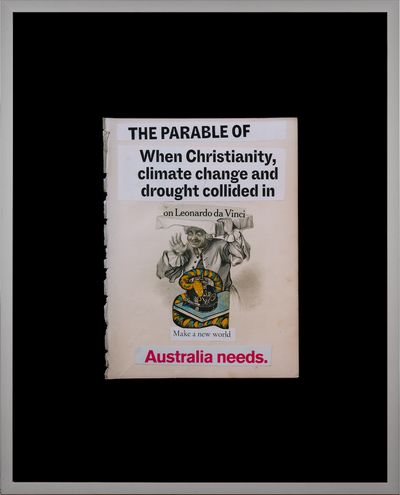

In This year, of change... (2020), that's Columbus in the middle—that's from a Hogarth print. The shark was from a Phantom magazine. The image has been enlarged and screen printed by Trent Walter. And the neon is from my neon archive. I have a neon collection as well—I use and re-use them. There's a lot of re-using and recycling going on.

AGKI read once that in the Medieval Ages, the average amount of information that a white male who died in his forties or fifties—which was the average lifespan of men at that time—imbibed, would be equivalent to a Wednesday edition of the New York Times. And that would be all the information that you would accumulate in your lifetime.

I came into This Year thinking about the volume of information that we're asked to unpack today—as communities, as individuals, as societies—at a time when the algorithm and fake news are colliding. How do we decipher and navigate this overload in a way that feels more ethical, more accountable, and less binary?

BAI think within that there's a lot of satire and humour. For one person, something can be really serious and intense, and for another it's not. Again, it's breaking down the everyday nature of how and what we see, but some things are absolutely more urgent, such as the environment, let alone human relations.

It's important to look at the satire and humour within that, and it is people like Hogarth and other international satirists, not just from the West, that allow us to do that. I think it's really interesting at the moment when lateral violence and systemic racism is really being exposed, where people are shifting.

I feel like it's the 1970s all over again—all these different movements are happening. At the top of the list is looking at the environment, but also, being responsible for histories. What does this mean to us, today? And to break down the hierarchical structures, which can be really confronting for some people.

Coming back to these works, I think it has been a really fun, playful thing, even though it's been really stressful to make this work in these strange times. I have a real fondness for neon, because I just think they're so beautiful and I go a bit gaga with them. The same with photography.

I think one thing that's really present in these works is fashion—fashion magazines and colour and form and shape and desire. I think that's really a wonderful mirror. I think that it's very hopeful.

In the present day, even though people are having a really hard time, and it's complicated, I think there is also a lot in our lives that gives us joy. For me, it's the metallic photography, and Sandy [Barnard] did an extraordinary job printing these. It's the shiny fashion magazines and the neon. How is it that we can have joy in our life as well, amidst this complexity?

AGKAn artist you've collaborated with recently, Lily Hibberd, asks if you could speak about the relationship between rupture and healing in your work?

BAYes. When we were talking about collage and pulling apart and rupturing things, it's kind of like the body and all its organs. How can we structurally put things back together?

I think healing is so important, speaking from my experience as an artist working with often difficult histories and memories. It is often a dangerous place to be, and the self-care and care of other artists is very important. It's very important the way that we talk to each other, even if we may or may not agree with some of the language or some of the narratives, because it is a complicated world. I think it's important to talk about these issues, as well, even within our arts practice.

In my process of making, and the relationships that I have, not only with my family and collaborators but also communities, it's really important for me and my soul, to be exploring these archives—these museum collections over the seas in Europe and the United States. I worked with Austrian artist Katarina Matiasek, who we invited to be part of NIRIN, and about ten years ago we worked very closely with several Aboriginal communities to repatriate human remains.

I've always had an affinity with language, with creating poetry and prose. It's a way to navigate the often-strict ideologies that we're often under.

Katarina is an artist but also a researcher at the University of Vienna in anthropology. When I went to see her about five years ago, we came across these important photographs of the community in Grafton, where there was the Grafton Aboriginal Home. It was one of the first experiments that the Australian government did with Aboriginal people there in the 19th century.

These are remarkable photos—very early photographs, from the 1880s I think, but the most important thing is that everyone's name was marked. I contacted Aunty Roberta Skinner who is one of the Elders there who has done a lot of research into photography, and we sent her a whole set of these, and now they're using it in a land claim, as they didn't have the names of people before.

For me, healing is not just about the work that I'm showing at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery right now, it's also about my greater, invisible identity. These activities are so important as an act of rupture and healing.

AGKSomeone else has asked: Your practice seems to focus on equal parts the visual as it does on words and text. Is this a conscious decision or does it evolve naturally throughout your process?

BAThat's a fabulous question. I've always done text, and I remember Chris Fortescue and Eugenia Raskpoloulos were two of the main influences in my life at art school. Even though I did interdisciplinary studies and I majored in photography, my major work was text on a wall, and text on velvet paintings, which are now in the MCA collection.

I've always had an affinity with language, with creating poetry and prose. It's a way to navigate the often-strict ideologies that we're often under. When I'm making these, I'm trying to unpack the world—what is the relationship between all of these things? I just wish that I spoke a lot more languages, so that I could incorporate them as well.

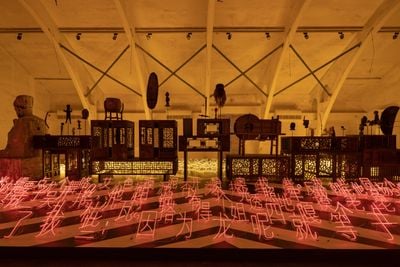

AGKOn that note, do you want to speak a little bit about the site-specific installation that you presented at the Wuzhen International Contemporary Art Exhibition in China, In Vision of Nuance: System of Exposure (2019)?

BAWuzhen is kind of like the Venice of China, and it's being refurbished by a very wealthy man who grew up there. There were three curators across the whole exhibition: Feng Boyi, Wang Xiaosong, and Liu Gang.

As part of the installation, I worked with LED text in two languages: Wiradjuri and the local dialect in Wuzhen. It was a translation of a poem I wrote. I also worked with cabinets that were repurposed from traditional windows and door shutters from Wuzhen, so we worked with local carpenters.

That's what I do a lot—I go locally to the communities and we just hang out and it's just, 'Hey, what's going on here? How do we reflect the pride within your place?' or, 'What are you up to?' or 'What are you doing?' We created these structures from the cabinets, and they became platforms for a series of cultural objects—some of them are fake, some of them are real—they came from all over the world.

It was a comment, really, on museums, and what is fake, what is real, what is the obsession with these objects that may or may not have power? There's a haziness around that, and I think that really affects identity and the class system, as well. It's pretty loaded.

AGKEven if you try to create a non-hierarchical structure, there is still an innate bias that exists—an unconscious prejudice that reasserts hierarchies.

For your Van Abbemuseum show, you used a Wiradjuri design that appears a lot in your interventions, but in the centre of this image there is the inversion of a Picasso, which was placed alongside Wifredo Lam's painting, Le marchand d'oiseaux (1962). As your practice has developed over the past 25 years, museums don't question you anymore, they don't say 'Please don't do that to our collection,' instead, they're kind of coveting you and cajoling you to come in and think about their collections in new ways.

It's a really interesting shift in terms of that turn to 'decolonise the museum' right now.

BAThis was an interesting proposal. I worked with the wonderful Nick Aikens. The Van Abbemuseum is really interesting because they're going through this period with L'Internationale, which is a collective effort by museums across Europe—Reina Sofia's one of them—to demodernise and decolonise, so they're looking at their own collections.

It's interesting that you say museums want me to come in and do things, because at the end of the day, when I say I want to do that, they'll tell me at the eleventh hour, 'Oh no you can't do that.' And that's happened a lot.

For that project, I tilted this painting by Picasso, Buste de Femme (1943), on its side. It's the Picasso that controversially travelled to Palestine. It was an extraordinary shift for that painting to go there. For me to display it on its side, took a friend to actually talk to the conservator to get it over the line; to do something to a painting that I'm pretty sure most museums would never allow, even though they're saying, 'Yes, we want to do something really different'.

I think this idea of decolonising the museum is another three-hour conversation. It's become a bit of a buzz term to create a momentum and a trajectory and I think there's many different versions and ideas of what that is, from radical to soft, to pretending to want to do something to not wanting to do something, to not letting go of power. But in actual fact, we have to understand that it is within that spark or frisson that there is change, and there is happiness within that change.—[O]