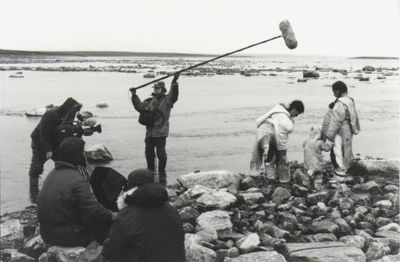

Candice Hopkins and Asinnajaq

Candice Hopkins and Asinnajaq.

Candice Hopkins and Asinnajaq.

Since 1985, artist collective Isuma has produced over 40 Inuktitut-language films celebrating Inuit culture. The collective's co-founder, Zacharius Kunuk, turned to filmmaking after returning from Montreal to Igloolik, having sold three sculptures to a gallery in order to purchase a camera. Born in 1957 on Baffin Island, Kapuivik on the Arctic Tundra, Kunuk attended school on Igloolik, where he returned with the video camera, and in 1985 received a professional artist's grant from the Canada Council for the Arts to produce the Inuktituk-language video, From Inuk Point of View. 'Inuit went from Stone Age to Digital Age in my lifetime,' says Kunuk. 'I was on Baffin Island, living on the land, and I saw the last of that era. Since we have an oral history, nothing is written down—everything is taught by what you see.'

Norman Cohn joined Kunuk on the quest to capture and preserve Inuit culture, relocating to Igloolik after seeing and feeling an aesthetic kinship with Kunuk's work. The two began working on a number of productions, including the 13-part mini-series, Nunavut (Our Land), and in 1990 were joined by Paul Apak Angilirq and Pauloosie Qulitalik to form Igloolik Isuma Productions—Canada's first Inuit video-based production company. Their film, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, became the first feature-length drama to be produced, written, directed, crewed, and performed almost entirely by Inuit. Premiered in 2001 at the Cannes Film Festival, where it was awarded the prestigious Caméra d'Or, the film reinterprets an ancient Inuit legend that was 'kept alive by oral history to warn us of the dangers of putting the individual before the collective.'

Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner embodies the community-based filmmaking that defines Isuma's practice. To reinterpret the legend, Paul Apak Angilirq spoke with community elders, amassing different versions of the story and consulting them on the film's usage of 16th-century Inuktitut language. Shot on location, with the performers dressed in costumes made by members of the community, the film is a collaborative effort. 'Collective survival depends on the art of working together for a common purpose, of putting the group before the individual', says Norman Cohn, who hopes this view of video will be expressed at the 58th Venice Biennale (11 May–24 November 2019), where Isuma will represent Canada at the Canadian Pavilion, marking the first presentation of art by Inuit at the pavilion.

On 18 March 2018, Candice Hopkins and Asinnajaq—two of the pavilion's five curators, along with Catherine Crowston, Barbara Fischer, and Josée Drouin-Brisebois—introduced the work of Isuma, and discussed the video installation One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk (2018), which they will be presenting at the Venice Biennale. This is an edited transcription of this presentation, which took place at Canada House in London.

Asinnajaq: Isuma is an artist collective that was started in 1985 in Igloolik with Zacharias Kunuk, Norman Cohn, Paul Apak, and Pauloosie Qulitalik. They wanted to bring the Inuit perspective onto the screen because it hadn't really been done before that, and they found it really important that stories that are important to us could be told from our perspective so it would feel that power is given to people who are directly going through these experiences.

Candice Hopkins: I think it's important to mention that the founding of Isuma—which can be translated as 'to think' or 'being in a state of thoughtfulness' in Inuktitut, but can also translate to 'to think for oneself' in English—was in Igloolik, where Isuma, along with the rest of the settlement, voted three times against access to television, because the content that they saw didn't represent their perspectives. Isuma saw an opportunity to start making not only this content, but within that content to actually reshape what media was understood as in Canada itself. Their platform, Isuma TV, is a platform not just for Isuma, but for all Indigenous film and video makers. As part of their interest in media democracy, anything that Isuma makes is available on that platform for anyone to watch anywhere in the world.

This idea of self-determination, as well as self-representation, has been at the heart of what Isuma has done from the beginning. The early videos, especially the ones from the eighties and early nineties, were first for Inuit audiences, and in fact they did not think that they would have much of a market in the south. For most of their early videos, there were no English translations, and it was only when they realised that people also wanted to watch this outside of Nunavut that they added subtitles. Since then, they have worked in a variety of forms, including what they call 'docu-drama', which, in a lot of ways, interrogated the form of re-enactment, as these are not re-enactments, but they go back in time in order to talk about moments, and what those moments were really like. A lot of those moments were instances of colonial traditions coming onto Inuit life.

Kivitoo (2018), like most of Isuma's releases, is Inuktitut with English subtitles, and the video is a story about displacement. At the moment, I think all around the world we are thinking deeply about displacement and the forced migration of people, and Kivitoo looks at an incident of displacement that happened in 1963 in response to the death of three people when the ice floor of their temporary home melted, and they fell through it. The Canadian government used what happened as an excuse to move everyone out of Kivitoo, and what you see in the video is their return. People started coming back in 1999, after having been moved 40 miles away to the community of Qikiqtarjuaq. From this archival footage from 1999, as well as the footage from their return in 2016, you experience the effects of that displacement, which was very traumatic.

I think for a lot of people this trauma didn't make any sense, because things like guns or harpoons were just burned or left to rot. But when you live in a place where everything has value, for a lot of people who were directly affected and for their ancestors, the loss of these items was deeply distressing. And not only that; the people who were forced to leave weren't told that their homes were going to be ploughed over and burned. There are links between Kivitoo and the new work that Isuma has made for Venice.

Asinnajaq I know you have lots to say about this, I wondered if maybe you wanted to talk about that?

Asinnajaq: I was recently going through the photo albums that my grandma very lovingly made—two for me, two for my brother, and two for my other brother. We all have these albums that document our lives. There are lots of pictures of when we'd go camping, and pictures of the landscape, just as there are of us being silly kids and trying to climb into refrigerators. When I see the photos of the landscapes, I can look at them with my family and we can say that this is here and that's there. The way that we have landscapes is the same way that you have family members. The landscape shapes our lives and is connected to us just as much as a person is, and I think that you can really see that in Kivitoo—that even after so many years, even if you only spent time there as a child, you remember it more than fondly, and still miss and long for it. I think that this feeling is really well reflected and explored in Isuma's work.

Candice Hopkins: Exactly, it's an exploration of the deep effects of forced relocation, which was instituted by the Federal Government of Canada, and many, many people took part, whether it was as priests or people who were hired to negotiate—although there was no negotiation—to move people into settlements and assign them not with names, but with numbers. It's something that Isuma is exploring more and more, and that is an essential part of their new video installation, One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk (2018), that will be shown at the Canadian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

Asinnajaq: One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk is very powerful. It explores, or it maybe reveals, some of the differences in passive communication when it comes to Inuk customs, and the bias and customs of the government employees who were trying to get people to move from their homelands into places that were more convenient for them—

Candice Hopkins: For the government, you mean?

Asinnajaq: Yes. And the work also explores the ways that people say 'no', or the ways that people act when they think you're embarrassing yourself and try to give you space to redeem yourself. The ways that we do that—how we express ourselves through word or action—can be different, and some people don't notice when they're completely missing what's happening. I think that in the tradition of the work that Isuma has done for these past three years, it brings the Inuk perspective in a time when we haven't necessarily heard that exact perspective yet.

Candice Hopkins: Exactly, and paired with the new video will be a series of live broadcasts called 'Silakut Live, From the Flow Edge.' The purpose of these live broadcasts is in fact to look at the ongoing way in which colonial traditions are shaping the homeland of Noah Piugattuk, a person who was very, very integral in the way that self-governance was formed in Nunavut. He was someone who never forgot the values of his homeland. And 'Silakut Live' looks at the ongoing effects right now—it's a live stream and live broadcast—of the proposed Baffinland iron-ore mine, which will transport some 30 million tonnes of iron-ore by railway, basically on the doorstep of where Noah Piugattuk was from. And I think for us, one of the ways that we understand this development of the Baffinland mine is a kind of ongoing relationship of what happens when you see land purely as a resource instead of as your home.

Asinnajaq: And the purpose of 'Silakut Live' is a kind of extension, or new way of thinking about this project that Isuma has been doing for a few years, which is called Digital Indigenous Democracy. That project is about finding ways to connect and bring information to more people, and 'Silakut Live' is a lot about making sure that you use as many ways as possible to inform people to be smart and to be able to make decisions about the ways that their homeland will be treated. That's something that is really important when it comes to the process of agreeing to have mines.

Candice Hopkins: Exactly, and maybe a point to end on is this idea that Isuma, from the beginning, framed their practices as part of a media art tradition and also in a tradition of media democracy, which involves a great deal of activism. This is very different from the way Inuit art has been narrated up until now.—[O]