Candice Lin’s Material Metaphors Conjure Invisible Entanglements

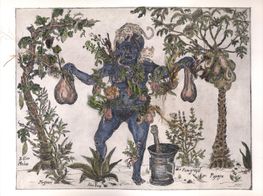

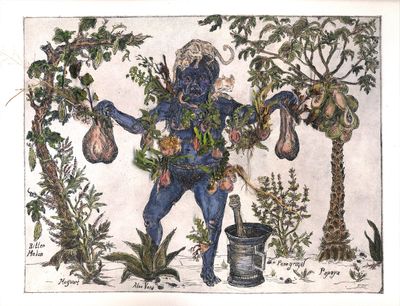

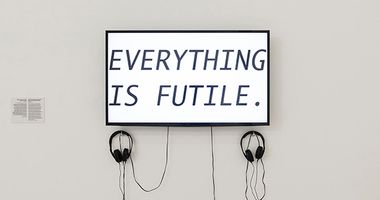

Candice Lin. Courtesy the artist and François Ghebaly Gallery. Photo: Ryan Lowry for Frieze Magazine.

Candice Lin. Courtesy the artist and François Ghebaly Gallery. Photo: Ryan Lowry for Frieze Magazine.

Candice Lin is kind of a historical alchemist, with installations arranging materials and substances into activated sequences that draw out intricate cartographies lurking behind macro-narratives.

La Charada China (Tobacco Version) (2019), for instance, on view in the artist's solo show The Agnotology of Tigers at Louisiana State University Museum of Art (20 October 2021–20 March 2022), comprises a man's silhouette made from tobacco leaves pressed into a steel and cement table laden with raw materials—cacao seeds, indigo, sugarcane, and opium poppy pods.

Those materials refer to plantation histories associated with the history of indentured workers, many of them Chinese, who came to the Caribbean and the American South in the 1800s to replace and supplement slave labour. Hence, the installation's title, which comes from a gambling game imported by those Chinese labourers that revolved around the drawing of a man's body, which soon incorporated Cuban, European, and African influences into its form—a distillation that speaks to the work's composition.

Positioned on the figure's abdomen is a distiller that boils materials found on the table, and drips through a system of tubes, pumps, and buckets to land on an unfired porcelain sculpture in an adjacent space.

A 2018 variation of La China Charada, first exhibited in Made in L.A. 2018, was configured for a group show at Lisbon's Galerias Municipais (6 November 2021–30 January 2022); this time with a man's imprint in a mound of red earth and guano from which sugarcane, opium poppies, and tropical poisonous plants were grown using growth lights.

Unearthing complex histories through matter is an ongoing theme in Lin's work. Swamp Fat (2021), shown in Prospect.5 in New Orleans (23 October 2021–23 January 2022), refers to late-19th century reports about the Mississippi River becoming gelatinous due to cattle river transportation and slaughterhouses throwing carcasses into the water, and the Slaughter-House cases triggered by white butchers complaining about sharing space with Black and non-white butchers.

Reflecting on these material intersections, Lin created swamp creatures and mounds from clay sourced from the former Louisiana fishing village Saint Malo, thought to be the first Asian-American settlement in the U.S. started by Filipino indentured labourers, and lard infused with the scent of rotting meat from Louisiana butchers.

'The history of Saint Malo as a multiracial fishing village and maroon settlement formed by a disparate group of people eking out a living on an unstable, marginal terrain interests me in ways that feel related to the intercultural mixing that is present in the indigo panels,' Lin told Catherine Damman for Bomb Magazine.

The hand-drawn and hand-printed indigo panels that Lin is referencing, form a large tent structure in Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping, shown first at Walker Art Center in Minneapolis (5 August 2021–2 January 2022), before moving to Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University (4 February–10 April 2022).

'These fabrics are drawn from historic textiles at moments of global trade, conflict, or colonialism where an intercultural influence on the designs is visible,' Lin tells me. 'They draw from a broad mix of cultural references, from Japanese, Korean, Taiwanese indigo cloths, to Portuguese and Dutch influences, and Indian and Nigerian textiles under British colonial influence.'

Surrounding the tent are ceramic pillars whose many-headed anthropomorphic forms reference ancient Zhenmushou tomb guardians from the Tang Dynasty, and the description of the devil made by George Psalamanazar, an 18th-century European man who pretended to be a native of Formosa, present-day Taiwan, even writing a book imagining the island's culture and language.

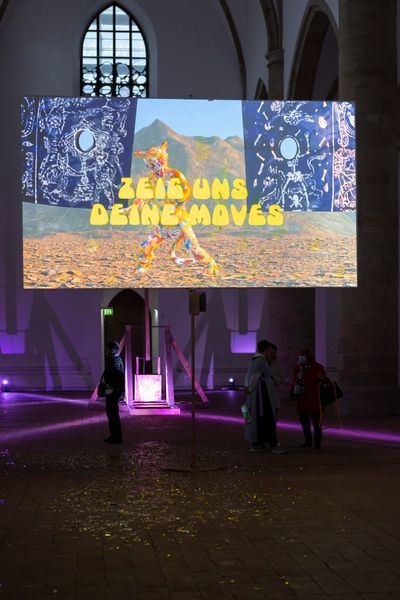

Within the space, conceived as a temple, a video animation shows a cat demon standing in a desertscape surrounded by the same patterned indigo fabrics, leading a calming session of qigong breathing and movement exercises.

The video is reconfigured for a German audience in The Glittering Cloud at Kunsthalle Osnabrück in Germany (26 June 2021–27 February 2022), which also includes new ceramic and copper-plated sculptures, and a lifesize sculpture of a trebuchet.

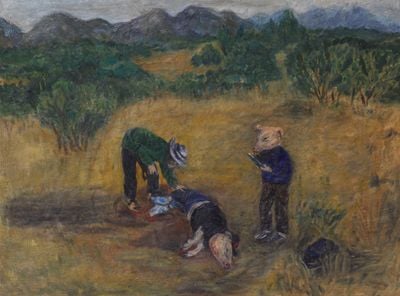

The latter form connects to Pigs and Poison, as it appears amid a body of work that will go on view at Spike Island in Bristol, U.K., (5 February–8 May 2022) after exhibiting at Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Zealand in 2020 and Guangdong Times Museum in China in 2021.

In this conversation, Lin, an assistant professor in the UCLA Department of Art, talks about Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping and Pigs and Poison, tracing the ideas which feed into works that confront history from a materialist perspective, where categories give way to entanglements.

SBYou've had a wave of exhibitions recently, creating quite the landscape to reflect on your work.

I'm reminded of your 2016 show at Gasworks in London, A Body Reduced to Brilliant Colour, and the alchemical installation System for a Stain (2016) that you showed there, combining fermented tea, cochineal ink, and sugar to distil a red fluid that moved through tubes, copper plates, and glass jars.

CLIt's interesting that you bring that up. I think that was the first installation I did where I was thinking about the process and the materials as part of the conceptual framework of the piece itself.

Before that, I was using materials to create representational imagery of the histories I was thinking about, but for that show I realised I didn't have to draw or do anything with this red-brown liquid made from cochineal, tea, sugar, and poppies.

The material and process of generating it could be the work on its own. So the sculpture itself became the system of distillation, fermentation, pumped circulation, and aeration that creates the liquid, and, in another room, the liquid stain slowly seeps out from the sculpture and grows larger over time.

How that relates to my more recent shows is that they're all continuing that line of thinking about materials and the histories embedded within them, and using the process of making the material as a way to re-animate or re-circulate meanings that have been lost in the dominant knowledge related to those materials.

I actually see Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping as a shift from my mode of working that started with System for a Stain.

In the Walker show, I didn't show the process of the indigo fermentation as the work itself, but created an environment that people can experience. The indigo textiles hybridise patterns that reference moments of cultural exchange, where the symbolism of the traditional indigo pattern on a textile adopt either the processes or the symbols of other cultures.

For example, the British colonial influence on Nigerian adire textiles, where you can see the British symbolism of the crown or union jack appear. Also, patterns on the textiles were no longer drawn by hand, but printed using stencils cut out from flattened tea tins, which were imported from British colonial India, and so they have a different look because of that, as well as the change in symbology.

SBThis idea of history's complexity expressed through material composition, which renders clean distinctions almost obsolete, happens a lot in your work.

CLI'm not interested in finding ways to make something easy to talk about, like cultural appropriation or a reductive essentialism.

Coming back to the indigo used in the installation, it's like, yes, these are beautiful colours, but they're also laden with histories of violence and oppression. But they are also simultaneously beautiful colours. So how do these things co-exist?

SBThere's a link between your Walker show in 2021 and your Gasworks exhibition in 2016 in the reference to George Psalmanazar. Could you elaborate on that connection?

CLThe way I have been thinking about Psalmanazar in recent works is slightly different to how I was thinking about him then. For Gasworks, I wanted to use the fake Formosan language he had invented to re-insert myself as the author within his text, which was based on sensational orientalist ideas he had.

I think he came back into my orbit recently because I was more interested in deconstructing race away from physical characteristics and thinking about this moment, when it was more about the performance of culture.

For Psalmanazar, racial performance was about what he did and how he dressed—eating opium and raw meat spiced with cardamon convinced others he was Asian in the 18th century European imagination. I think that's fascinating.

There's a lot of projection and fantasy and orientalising within Psalmanazar's text, but I think it's more interesting to try and think about it how it complicates our assumed and naturalised ideas about race. To ask, what does this historical narrative have to offer, rather than just anachronistically calling it out from our contemporary point of view and politics.

I'm not interested in finding ways to make something easy to talk about, like cultural appropriation or a reductive essentialism.

SBThat notion of trying to embody culture through consumption recalls ideas of othering being rooted in the desire to consume the other, which comes back to the way you deal with materials. How do these ideas manifest in Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping?

CLYes, I'm really interested in the idea of consumption and even staged some performative meals in 2014 at the Delfina Foundation and in 2017 as part of the Sharjah Biennial that took place in Beirut.

In Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping, I was thinking a lot about zones of contact and 'partial consumption'. By 'partial consumption' I'm thinking about the scientist Lynn Margulis' idea of new forms of cellular life occurring when one cell partially consumes but can't fully digest the other, and I feel that what I'm doing with the indigo textiles speaks to this violence of creation but in a cultural way.

I'm also thinking about zones of contact not just between cultures, but between species, and between individual bodies.

Maybe I was being overly hopeful but I remember thinking the Walker show would happen when the pandemic is over and everybody would just want to be really close to each other, touching the art and hanging out together.

So I thought I should make some kind of space that feels like a place of rest. It's really soft, too, because it's lined in rugs and has these ceramic cat pillows you can rest on. I imagined it would be interacted with and very tactile.

SBBut then you have these pretty terrifying many-headed totemic sculptures.

CLThe Psalmanazar reference is in the ceramic pillars in the middle of the tent, which are based on his drawings of the idol of the devil, and the link between these pillars and the tent is that they are framed by this global imagination of what another culture looks like.

So there are these hybrid images both in the pillars and on the indigo fabrics composing the tent that try to reckon with and partially consume what is 'other' to oneself.

SBPrinted at the entrance of the tent are the words 'Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping'. Why did you choose those words?

CLI think we all relate to this feeling of seeping and rotting, especially during this pandemic where we are all isolated and stewing in our own juices; weeping is also about the grieving of this period, and the resting indicates the potential for this to be a time of reflection, to really ask what this global existential crisis can reveal to us.

But the words also reference the fermentation process of making indigo, because part of my research was making different kinds of dye vats and some of them, like the urine one or the old fruit one, smelled really bad and rotten.

SBThat process of fermentation also speaks to entropy as an equaliser, no? We all rot in the end.

CLEqualising yes, but also decay is about new life. Getting the most beautiful indigo colours requires the proper decay and eating of the decay by the bacteria, to reduce the oxygen present in the vat to the right level.

SBThere's also this futurist angle to the installation in its compressing and condensing of references; like an archeological site of a future history.

CLI would hope so. I mean, it's weird because Pigs and Poison was made before the pandemic, and as it turns out it was about the future, but only because the future is history.

SBThat idea of Pigs and Poison being a future history makes sense, since you created the work before the pandemic hit. Could you introduce this exhibition project?

CLThe show was supposed to open at the Times Museum in March 2020, but it was postponed until March 2021, and opened first at Govett-Brewster in New Plymouth, New Zealand in August 2020.

I feel like when something happens, like the pandemic, you need time to think about its impact , digest it, and live with it. The feeling that the show might be perceived as this quick reaction made me feel uneasy.

The show is about looking at the history of plagues at the turn of the century—between the 19th and 20th centuries—and the way they were racialised, and how it fits into a long history of racialisation and ideas of belonging and citizenship.

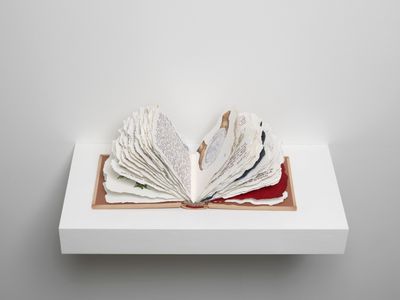

The research was done in 2018 and 2019 and came from the research I was doing on porcelain, which was used as a scientific filter to study diseases, and has been part of what I've been thinking about since 2017.

One of the diseases that I studied was tobacco mosaic virus, which the scholar Jih-Fei Cheng wrote about. The disease was described in racial terms as 'going mulatto' and the leaves were described as turning yellow and wooly. The work I was making reflected on the historical connection between contamination, disease, and virality and its links to race. Then the present interrupted.

How did you feel when you realised your body of work exploring a historical plague was connecting to a pandemic unfolding in real time?

Of course it was timely and relevant in that it showed how history repeats itself. But I felt kind of weird about it. Even though the exhibition had been packed and shipped, part of me wanted to take the show back and change it. It felt like it was definitely going to be misunderstood as being about the coronavirus, as if I was capitalising on it or directly responding to it.

I feel like when something happens, like the pandemic, you need time to think about its impact , digest it, and live with it. The feeling that the show might be perceived as this quick reaction made me feel uneasy.

One thing that I have been thinking about more lately is the relationship between the racialised body and the non-human animal, which became really timely with the conversations around wet markets and the origins of the virus in bats, because 19th-century plagues linked Chinese residents and rats to their source. I feel like maybe that is the direction of my research now—trying to think more about animality.

SBThat Chinese communities in the 19th century were seen as sources of plague speaks to a historical thread running through your work: of the so-called coolie trade, which refers to the mostly Chinese indentured labour that replaced slavery in the 1800s. What does this history mean to you?

CLIt's actually not that personal. Of course, I'm interested in it in a particular way because I am Chinese American but it's not tied to my biography. For me, it's an interesting global moment in history because it complicates how we think about freedom.

I first got interested in this history after reading Lisa Lowe's book, The Intimacies of Four Continents (2015), which looks at the erasure of this history of labour. Politicians at the time spoke about it as a solution or a transition out of slavery, so it was very much thought about as a way to maintain the exploitative aspects of the status-quo while officially calling it free labour.

Lowe's book asks: what do we get out of erasing this kind of history? If we did address it, that would force us to think about the messiness of this so-called transition from enslaved to free; that there are all these other forms of liminal unfreedom that are not the same as slavery, but are related to it.

It's complicated and forces us to have to reckon with all the after-lives of slavery and variations of unfreedom that are still present today rather than treating it as a chapter we have resolved and moved on from.

I grew up learning about the Chinese railroad workers and the gold rush, but I'd never heard about the term 'coolie', which, after making work on the subject matter I learned through conversations with people—in particular the amazing writer Shani Mootoo, who contributed to the Pigs and Poison catalogue—that 'coolie' is a really derogatory word in the Caribbean context.

I was using it as a normalised academic term and we had an email correspondance about it that was helpful for me to learn from.

Things come up that are disturbing or aren't articulatable, and I want there to be room for them to be less neatly explainable or categorisable.

But growing up, I hadn't heard about that history of this specific form of Chinese indentured labour. My parents never learned about it during their education in Taiwan either.

Then one interesting thing happened during the Times Museum exhibition at one of the programmed events. A scholar mentioned that this history was not well known but in recent years the Chinese government has picked it up as a kind of nationalistic story about overseas Chinese immigrants' exploitation and victimisation at the hands of Western imperial powers, and their perseverance to still succeed.

That's something I wish I'd known about before making Pigs and Poison, especially for the Chinese context.

SBThat's interesting this history is being taken up in China as this nationalistic story, because as you point out in Swamp Fat, while this history of indentured labour was very much populated by the Chinese, and the Chinese are mostly associated with the term 'coolie', this labour force was not limited to Chinese workers, right?

CLYes, for Swamp Fat, my installation for Prospect.5, I was researching intertwined racial histories in Louisiana, one of them being Saint Malo. Saint Malo is recorded on the historic marker, which marks the site where the fishing village once stood, but has long since been destroyed by hurricanes, as a Filipino settlement.

It was thought to be a community started by Filipino indentured labourers who jumped ship en route to Spanish colonies, but were joined by Chinese indentured workers, and possibly Indian indentured workers who were also associated with the 'coolie' term. It was also an area where slave maroon communities lived and the name itself is the name of a important maroon community leader.

In my installation, there were ceramics made from mud dug from the swampy mud around the location Saint Malo had been, which I sculpted and fired into the shape of swamp creatures whose carcasses are split open and filled with scented lard.

The lard faintly smells of sour decay, and references the Slaughter-House Cases. The use of lard also connected this work to works in Pigs and Poison, which used lard as a material in some of the sculptures and paintings.

SBReturning to Pigs and Poison, could you walk us through the show? What's the meaning behind the title?

CLPigs and Poison takes its title from a phrase used in 19th-century trade jargon. Chinese immigrant workers were referred to derogatorily as 'pigs' and the poison was the opium that the British and other imperial nations were pushing as their primary trade product to exchange for porcelain, tea, and other Chinese goods, despite the fact that trading opium or bringing it into the country was illegal.

Many scholars have noted that the chaos, poverty, and destabilisation caused by the opium trade and subsequent Opium Wars enabled the mass exploitation of Chinese immigrants to become low-paid or coerced indentured labour.

In the installation, there's a life-sized sculpture of a trebuchet, which a gallery attendant needs to trigger so it shoots projectiles made of lard and bone-black pigment. Then there are these fleshy lump sculptures around the space, which are purring.

These sculptures reference historical descriptions about the siege of Caffa during the Black Death, when the Mongols supposedly flung plague-infected carcasses over the city walls to infect the city, and I wanted to create these skinned carcasses that were breathing.

There's also the presence of lard in the paintings, which are painted with wax, lard, and pigment, a V.R. piece in which you see the sculptures in the show as dystopian future relics, and the trebuchet is slinging flesh lumps at you as your body is melting into the carcasses that pool around where your feet should be. I was thinking about it as a visceral-alternate experience of the exhibition.

SBSo not as inviting as Seeping, Rotting, Resting, Weeping then!

CLIt's funny because thinking about the relationship between the Walker show and this one, Pigs and Poison, is brutal. You come in and the first thing you see is this barricade stained with bone-black pigment painted to look like mold topped with razor wire.

So you're entering into a space that's barricaded, which is a little on the nose because it's thinking about belonging and borders, and there are all these things being hurled at you.

SBWhat do the Chinese characters carved into the barricade mean?

CLIt's a Google translation of the phrase, 'meaningless squiggles', which comes from John R. Searle's 1980 text Minds, Brains, and Programs, in which he uses the Chinese language as part of a thought experiment around the inscrutability of artificial intelligence. I got my dad to write it out in his calligraphy and then carved it on the wall, and on the other side, the phrase is in English.

SBThere are also works that connect back to your interest in plant materials and their composition, right?

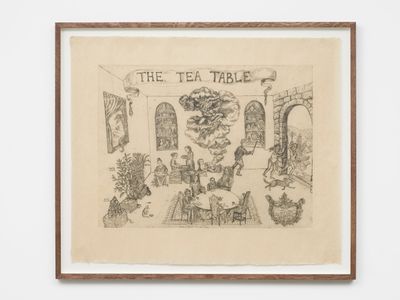

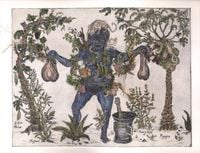

CLThere's indigo handmade paper made from the pulp of different plants that have to do with plantation economies and global trade. And then, there's these tincture drawings that I make after ingesting tinctures of those same plants, like sugarcane tincture, opium poppy tincture, and tobacco tincture.

The process of making these tincture drawings is that I steep the tincture for six weeks shaking it every day. Then, I take a dose of the tincture and make these small letter-sized drawings while the tincture is still in my body.

To create the drawings, I use ink that I make out of galls that form when parasitic wasps lay their eggs in oak trees. This oak-gall or iron-gall ink was the ink used for a lot of medieval manuscripts and also by the U.S. post office. So I think of my drawings as being drawn from the same material that European archives and bureaucratic paperwork were written in.

I started this series around 2018. I was really struck by how Saidiya Hartman reads archival images in Wayward Lives (2019) and the way her whole project in all of her books has been these different iterations of reckoning with the voids left in archives and dominant histories.

...it's weird because Pigs and Poison was made before the pandemic, and as it turns out it was about the future, but only because the future is history.

I was trying to think about how I could do that as a visual artist in a way that couldn't be dismissed. I think this is a worry of Hartman's as well, I've heard her speak publicly about her concern that the work gets dismissed as fiction or merely speculative.

So I was thinking about how you can make visual artworks that address those histories and aren't just seen as an individual's fantasy or imagination.

SBThat question of making visual artworks that address histories without being dismissed as fantasy speaks to how you manifest historical stories through sculptures and material installations that don't rely on archival or essayistic form.

Some people have a conception that artworks engaging with history are didactic historiographies, but they forget that art is unburdened by the demands of linearity.

CLI don't think about my work as didactic because I'm not an academic. I'm just learning things I want to learn, and I feel if the work is read didactically, there isn't that much for people to learn from it. It's about trying to work through history in this way that's not an essay. Things come up that are disturbing or aren't articulable, and I want there to be room for them to be less neatly explainable or categorisable.

Could you talk about your process of thinking through the form of the work in response to your research?

It's a hard process to describe because it often happens while I'm making it and it's somewhat intuitive and changes. I mean sometimes it doesn't, and I'm usually less satisfied with those works that develop more linearly from an idea from my reading.

It's funny because I'm a teacher and I always advise my students to have your idea and your research, but allow something larger than your own thinking permits to permeate the work. That way the work can be larger than your own thinking, and beyond the limitations of one individual mind.

I give myself this advice, too: the work becomes better when you don't necessarily control everything about it and you're open to receiving meanings. I have a mental picture of a cosmic cloud of ideas that we sometimes get to tap into when we are open to it.

SBSpeaking of being open to receiving meanings, what is it like seeing your work engage with different contexts, from New Zealand to New York?

CLIt's an opportunity to have conversations with people who are encountering the work and learn something from people who know more about these histories I'm working with and are often more personally intertwined in these stories. It's really interesting to hear things I didn't know about in my research.

Often, people don't necessarily understand all the references I'm trying to get at, but that doesn't really bother me, because they're just having a material encounter with the work and it can be different for everyone.

Sometimes I get weird projections; the work gets essentialised to the artist. Like, 'you're making work about Chinese indentured labour because it relates to your family history,' which is not true and I push back on that. Other interpretations I'm very welcoming of.

SBOn that note, could you introduce the two figures in Pigs and Poison, who are formed from ceramic masks and an assemblage of fabrics and hair?

CLThose two figures were originally made to accompany this installation of La Charada China (Tobacco Version) (2019) at François Ghebaly, where they became the witnesses to this installation that performed a distillation of this dark-brown liquid created from tobacco, indigo, and sugarcane boiling together.

The steam from the heat distilled the liquid so that it ended up being clear as it dripped down a porcelain-tiled basin and down a drain. The 'Witness' sculptures were positioned as counterpoints that drew attention to the invisible clear liquid as it disappeared without a trace. I thought it made sense to bring them into Pigs and Poison as witnesses to the histories that I'm talking about.

Each sculpture is wearing a ceramic mask. The masks reference scold's bridles, which were used in mediaeval times to discipline subversive people, often women who were not submissive. There's also a reference to the iron muzzles, which were put on disobedient slaves. They're both mechanisms that were used to repress and silence speech that might incite a revolution.

For me, the masks are references that try to draw a lineage between forms of bodily and speech constraint in relation to ideas of unfreedom. And the show is about thinking through these different ways that people have historically articulated unfreedom and found ways to bear witness to or resist those conditions.

I give myself this advice, too: the work becomes better when you don't necessarily control everything about it and you're open to receiving meanings.

SBHave people taken offense to you using the iron muzzle, given its reference to slavery?

CLThere was one case in which a writer gently expressed disapprobation of my use of the iron muzzle, saying it is possibly appropriative. I guess I hadn't thought of the iron muzzle as being specific to enslaved people of African descent, and I thought there was something interesting about the shared histories that are connected to these violent technologies of restraint and torture.

In my research on Chinese indentured labourers, they were sometimes put in stocks that had been invented during the Indigenous Encomienda Labour System, before they were used on plantations against slaves of African descent.

Unruly Chinese immigrants, as well as other groups of people, were also lynched on trees and makeshift gallows, another symbol that is predominantly associated with violence done to Black people, but is actually not exclusive to that group of people. What comes to mind here is the research of artist Ken Gonzales-Day, which looks at imagery and records of Latinxs, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and African Americans, who were lynched in the American West and nationwide.

Rather than lessening or appropriating the impact of these violent technologies, my aim was to use this imagery to trace a continuum of historic moments.

I was connecting but not equating the violent technologies that were developed to discipline enslaved people of African descent to the earlier restraint and torture devices used on enslaved Indigenous people in the Encomienda System from the 16th to the 18th centuries, or similar devices used on subversive people in medieval Europe, disproportionately female workhouse inmates, during a similar time period.

I think this kind of trans-historical desire to trace connections across time and space borrows from scholars like Silvia Federici's work in Caliban and the Witch (2004).

SBThat condition of entanglement, which resonates across your work, comes back to those witness sculptures 'watching the invisibility disappear'. Could you elaborate on that?

CLIt relates back to the idea of the tincture drawings. Like, how do you bring into the space something that is bearing witness to, or not letting history disappear fully, even if it's not tangible or visible? There has to be some way to slow down the moment and make space to wonder about the thing that was made invisible. The witnesses came out of that impulse.

I feel like as an artist, I'm often in the act of bearing witness. I think it's something that James Baldwin talks about. I think he was saying that as a writer you bear witness to the particularities of who you are and you bear witness to the moral failures of the nation, and this makes history and culture.

For me, an artist—or really any layperson who acts as a witness—creates a record of what they have seen, and this can serve as an alternate history.—[O]