Christine Sun Kim and Niels Van Tomme Activate New Possibilities

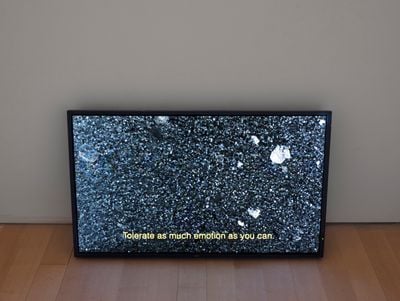

Niels Van Tomme and Christine Sun Kim. Still from interview for Tallinn Art Hall. Courtesy the artists.

Niels Van Tomme and Christine Sun Kim. Still from interview for Tallinn Art Hall. Courtesy the artists.

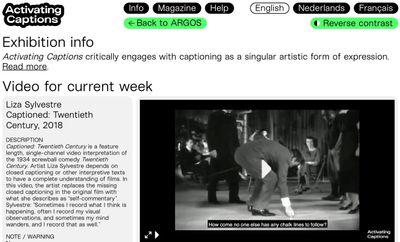

Activating Captions (6 April–8 June 2021) is an online platform and physical window display presented by ARGOS, the Brussels-based institution focused on the production, distribution, conservation, and advancement of critical audiovisual arts.

Curated by artist Christine Sun Kim and ARGOS director Niels Van Tomme, the project critically engages with the process of converting audio and visual material into text through a display system, which is essential, the curators note, 'for the Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing, as well as numerous others, such as people who are learning a new language'.[1]

An assembly of artists' videos and commissioned writing aim to probe the limits and potentials of the format and open up vistas to imagine a 'more expandable future' for an audiovisual culture that is currently far from accessible to all.

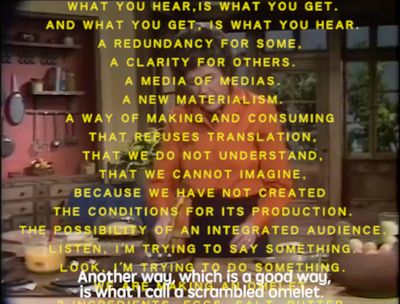

Among them is Liza Sylvestre's Captioned: Twentieth Century (2018), for which the artist annotates a 1934 feature-length comedy Twentieth Century with her own 'self-commentary' of the action as she perceives it, and Carolyn Lazard's video A Recipe for Disaster (2018), in which the artist presents a powerful text- and sound-based intervention over an episode of Julia Child's cooking show The French Chef, which in 1972 became the first programme to include captions as part of broadcaster WGBH's drive to include captions for deaf and hard-of-hearing audiences.

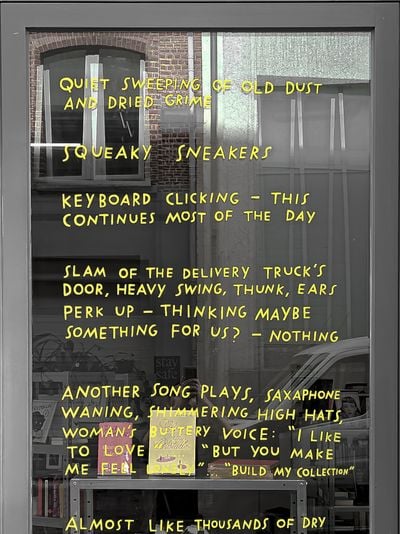

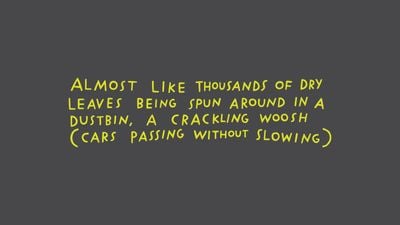

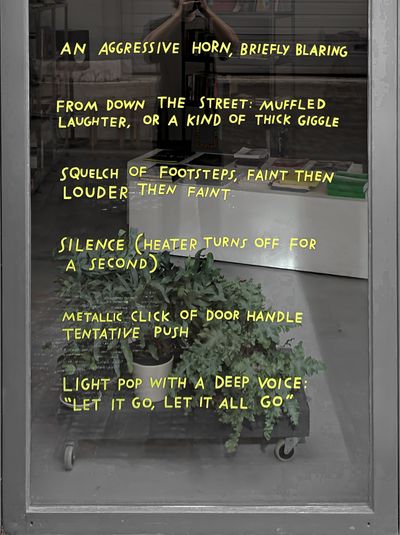

A site-specific intervention by visual artist Shannon Finnegan in collaboration with Sven Dehens and Chloe Chignell, Rue des Commerçants 62 Sounds (2021), involves vinyl captions attached to a street-facing window by Finnegan, Dehens and Chiggnell, which documented ambient sounds they observed while minding the rile* bookshop in the ARGOS building.

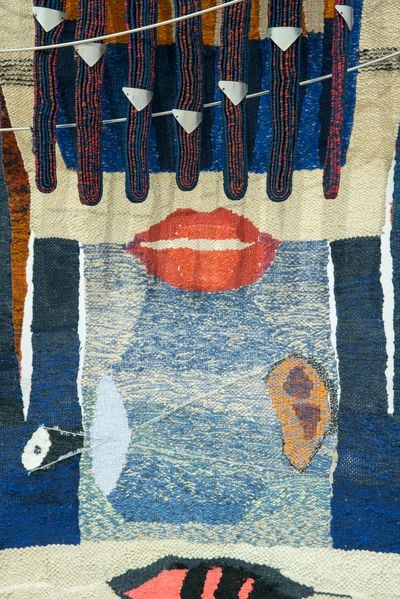

Activating Captions follows on from Disarming Language: disability, communication, rupture at Tallinn Art Hall (14 December 2019–24 February 2020), a group show that framed disability beyond its stigmatisation curated by Kim and Van Tomme and organised in partnership between Tallinn Art Hall, Estonia's Chancellor of Justice, and ARGOS.

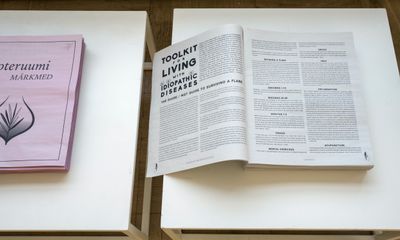

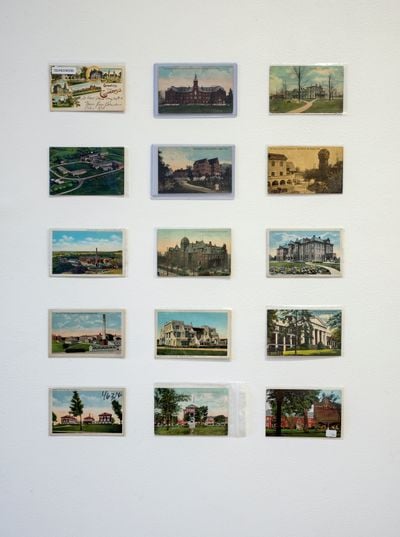

Works by artists, graphic designers, writers, and activists challenged ocular-centrism in art by articulating a broad landscape of sensory experience. Among them Jesse Darling's Mene Mene (2017/2019), graphic posters spelling out messages in Blissymbolics, a communication system developed by Charles K. Bliss during WWII that came to be used as a means of communication in Special Needs education, and Jeffrey Mansfield's Architecture of Deafness (2019), an installation of documents charting an architectural history of deaf schools mainly in the U.S.

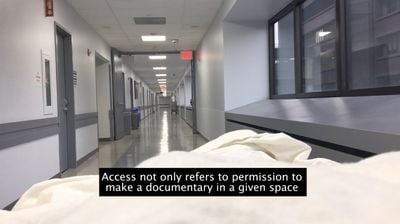

Carmen Papalia & Heather Kai Smith's three-channel video animation Open Access: Claiming Visibility (2019), which offers a non-linear interpretation of 'Open Access', a conceptual framework for accessibility and mutual care developed by Carmen Papalia, which narrates Heather Kai Smith's animated renderings of archival protest documentation, including scenes from the 1977 '504 Sit-In' disability rights protest that saw around 150 people occupy the fourth floor of a federal building in San Francisco to demand compliance with the Rehabilitation Act, passed in 1973 to prohibit employment discrimination based on disability.

The purpose of Disarming Language, Kim and Van Tomme wrote, 'lies in imagining new conceptual and experiential frameworks that use language and communication in innovative ways – through, with, and beyond disability – advancing a radically more expansive point of view past limiting ableist perspectives and possibilities.'

Where Disarming Language approached this purpose by loosening and destabilising the rigid boundaries of the definitions that define and all-too-often reduce bodies in the world, Activating Captions takes a common communicative construction to push its limits and 'create a rupture which allows future possibilities for disability awareness to emerge.'[2]

Activating Captions is an expression of a much longer collaboration between Kim and Van Tomme, which started when Van Tomme, at the time director at de Appel in Amsterdam, invited Kim to work on what would become BUSY DAYS with Christine Sun Kim (5 May–20 August 2017), which staged five artistic interventions throughout Amsterdam.

In this conversation, Van Tomme and Kim elaborate on the ideas and thoughts that run through their collaboration together, while reflecting on the realisations and possibilities that have emerged as a result. The discussion took place with simultaneous interpretation by Beth Staehle.

SBLet's start with how you began working together. Niels, you said you first collaborated with Christine in 2016 at de Appel, where you were chief curator and director. Could you talk about that project, and how it led you to invite Christine to co-curate Disarming Language?

NVTCurators often build a practice that involves regularly working with the same artists, so when putting together a programme for de Appel I challenged myself to work with artists I had not worked with before.

An interpreter is a solution, but it's not actually always an enriching experience because it doesn't necessarily ensure that every individual can have a meaningful engagement with the institution, because there's still this gatekeeper mentality.

I really wanted to work with Christine, because she was an artist I was fascinated by but had never met in person. After a studio visit in Berlin, we agreed to work together on BUSY DAYS, which really pushed the possibilities of what could be done with presenting contemporary art in an institutional setting. It was fantastic to work with Christine, because she's so actively involved in the thinking process behind an exhibition.

When we started working on the show in Amsterdam, Christine asked me during our first night out, 'Do you like captions?' That question really planted a seed for the projects we've worked on since, including Activating Captions.

We share a fondness for captioning and subtitling culture, even though it comes from very different life experiences. Christine relies on captioning and subtitling because she's deaf, and I grew up in a context where subtitling is omnipresent. Belgium is a trilingual national context, where we even subtitle local dialects in news broadcasts. So for me, subtitling and audiovisual media are intimately and naturally entwined.

At a certain point, I was invited by the Tallinn Art Hall in Estonia to think about an exhibition about disability. Of course, I was honoured that they asked me to do this, but I also realised that I wasn't an authority on this subject matter.

The notion of how to make such an exhibition had to be reconsidered entirely, so I couldn't rely on habitual modes of exhibition-making; I really needed to be pushed out of my comfort zone. That's when I contacted Christine and asked her if she wanted to co-curate the project in Tallinn.

SBChristine, Disarming Language was the first time that you curated a show. How did you experience that trajectory of working together with Niels in 2016 to the Tallinn show in 2020?

CSKWell, about my question about captions, the joke is that I don't remember saying that!

Of course, I know in the U.S. there's a weird relationship with captions—we don't share the same relationship to captions that exists in Belgium, for instance. I wish that we had open captions in general, not closed captions, and I wish that captions were omnipresent as well.

When I engage with English-speaking countries, they tend to resist captions a lot, or easily get flustered. Like when Parasite (2019) won best picture at the Oscars, but everyone complained that the film had to be subtitled. When I did some work in London, the discourse around captions was just, 'Can't we just do without?'

Non-English-speaking countries seem to be more receptive to captions and subtitles, and that is partly because most Hollywood movies are produced in English and people are used to them being subtitled. Now my stance is, if you don't like captions, I don't think we can be friends!

My attitude towards working with people oftentimes comes down to the ability to collaborate. This is the case when I work with interpreters and in the art world, where I have similar experiences about collaboration. It feels like everything that I do is a collaboration. I can't have this hierarchy.

When I worked with Niels at de Appel it was such a positive experience. Although Niels doesn't sign, I felt a lot of synergy between us, and we shared a lot of similar tastes and aesthetics.

Fast forward to Tallinn, and I will say that at first, I had a sense of resistance to the project. I have worked with museum educators and as a museum educator myself, and I have seen how difficult curatorial work is. I have also encountered curators who were not very flexible because they were fixed to their own vision. But if you want to offer accessibility, it requires flexibility.

That being said, I was curious and said yes to Niels and quite frankly, working on these exhibitions has affected my practice a lot. I have found myself becoming more aware.

Thinking about the notion of ambiguity is very interesting, because if you think about captions as access, which is a limiting way to think about captions, of course you're thinking about how to make things as clear as possible.

For a long time, I didn't consider myself as a person with disabilities. A lot of that has to do with the complicated relationship that the deaf community has with the disabilities community, because deaf people are often still marginalised because of the language barrier. I grew up as deaf, but not disabled; but now I call myself disabled and deaf.

I really do enjoy the part of curation where Niels and I are able to choose and invite artists that we admire. For me, that's the power that comes with curating, and it's a responsibility that I haven't had access to as an artist.

SBChristine, in an interview for Disarming Language you were upfront about the institutional framework, which related to how you were engaging with the term disability for that Tallinn show. Disability is often seen as this monolithic term, just as much as the institution operates as a kind of monolithic framework, both of which you actively resisted.

That also relates to what you've mentioned about the show: that once you go into the term disability, or disabled, it turns into a constellation of independent experiences that are all quite different, and hardly uniform. How this manifested in Disarming Language was as an exhibition that activated senses and sensibilities in a heterogenous way.

Could you talk about how Activating Captions is building on this work?

CSKI'm in a group e-mail thread with this scholar slash teacher called Lawrence Carter-Long, and I'm just getting an e-mail about how the word disability has functioned more like a medical diagnosis, so it's been hard to expand that term and meaning as well.

Carter-Long mentioned that 'dis' tends to mean a lack, but in Latin, dis usually means two directions. So when you say disability and go to the Latin root of it, it actually enhances the meaning, in my opinion. It doesn't mean the lack of ability; it just means the other direction.

When it comes to the institution, of course almost every industry in the world isn't designed for people with disabilities. That's the system which we inhabit. Growing up, I always felt like I was in pursuit of whatever system had been constructed, and if the system was going to add more people, meaning 'be accessible', it was always a half-assed attempt to do that. For example, if they wanted to give deaf people access to the programming, they'd bring in an interpreter with the view that it would solve everything.

An interpreter is a solution, but it's not actually always an enriching experience because it doesn't necessarily ensure that every individual can have a meaningful engagement with the institution, because there's still this gatekeeper mentality.

I know that Niels and I were trying to find some different models to work from for our exhibitions, and there wasn't really anything out there. We decided to add more criticism, to add to the discourse. Instead of accepting what's readily available, we realised we were going to have to create something new for ourselves.

NVTBasically, Activating Captions builds on our work for Disarming Language. Concretely, the thinking process happened when we were preparing Disarming Language in Tallinn.

Disarming Language really started from this discomfort of addressing disability through contemporary art. One of the unwritten rules that we committed ourselves to is to only work with people who are disabled, or who experience disability firsthand.

Activating Captions doesn't mention disability per se in its description, but having said that, our working methodology has been exactly the same as the one for Disarming Language.

Disarming Language was also an assignment from Tallinn Art Hall and the Chancellor of Justice in Estonia to curate an exhibition that raises awareness around this topic. So we were looking for a way to curatorially and critically approach this. It was a very different starting point than the one we had for Activating Captions.

In the beginning, we thought that Disarming Language would travel to ARGOS, that we would reinstall the show there, and maybe add more works and think of different approaches to add to the exhibition. But the more we worked on that idea, it became impossible to disentangle Disarming Language from Tallinn as we realised that the project was intimately entangled with that context.

When thinking about ARGOS, where I became a director in 2018, we thought about how this is an institution specialised in audiovisual art, so we started to think about captions as something that related to ARGOS specifically. That's how the project originated.

I know a lot of deaf educators are doing tours and guides in different institutions and do the work to make sure their audiences are welcome, but the truth is that a lot of deaf people don't feel welcome in institutional spaces, so they don't go. Making people feel welcome ultimately makes the institution accessible.

There is this myth around audiovisual arts that I am constantly confronted with, which is that it is the most accessible art form available, because it references the language of mass media and pop culture.

But while it's true that for a large part, perhaps, a lot of film and video art is more relatable, it's also a myth, because this is also an art form that is inaccessible to many people. We wanted to play with that idea, and think about what video art needs to advance to the next level.

The use of captions, which is still a bit of a taboo for a lot of audiovisual practitioners, is definitely such an area. That's what we wanted to activate. So Activating Captions is not only about the activation of captions by artists within the artworks that they make; it's also an attempt to activate the audiovisual arts community to think about captioning practices more consciously.

CSKThe interesting thing about Disarming Language is that when we were in the process of conceiving the show, we were also trying to figure out who on the spectrum of disability we should include. Is it cognitive? Is it motor?

We were figuring out where to start, how to start, how to provide access, what kind of access we could provide, and asking ourselves whether it should be integrated or not. Also, as the show was happening in Estonia, we had to consider Estonian language and sign language.

When it came to Activating Captions, things felt a lot smoother because we had already considered a lot of these questions through Disarming Language.

SBThinking about how Disarming Language sought to disarm the definition of disability within the framework of the institution, could you expand on this idea of captions as a taboo within the realm of audiovisual arts and the challenge of presenting an institutional exhibition that disarms this particular taboo?

NVTI don't know if it really is a taboo, but it has happened before when I've worked with an artist and tried to talk about subtitling or captioning and it became a very difficult conversation, because the work wasn't conceived for it. That is the artistic intention.

So if a work isn't conceived as such, then you get a kind of Netflix captioning, which is fine, but it's also very limiting in what it can do, because it's an afterthought. It's not considered a part of the process of creating an audiovisual artwork.

I think that's also where this taboo comes from. If it isn't thought of at the very beginning, it comes as an afterthought that has been added for accessibility reasons. It's not a habitual way in which an artwork is presented. In that sense, the project is also a call to action towards a more proactive approach to captioning. A lot of these possibilities are yet to be explored.

What's so unique about Activating Captions, I think, is that captioning, rather than video, is the medium in which these artists are working, and that creates an incredibly unique constellation.

Video is quite unique as a medium. You can do so many things with it that go beyond how to show something or make something legible. It's the medium that has the potential to problematise itself and to make that a part of its being, and that critical potential is super interesting to think about.

CSKAbout captions being taboo, I think part of it has to do with the fact that access is an ugly word. It typically denotes that something has to be done for a specific audience.

You know how the art world is—it's super exclusive and clique-y, and those things can be fun words at times. What I see is that artists use captions as something that disrupts the imagery of their work; they'll look at it as something that kind of ruins it.

There is this myth around audiovisual arts that I am constantly confronted with, which is that it is the most accessible art form available, because it references the language of mass media and pop culture.

But often, picture and text do go well together, and what I've started to see in video art is more words or captions on the screen that seems quite playful, and I've seen a lot of flexibility. There's just a lot of material to play with. It might not necessarily be accessible, but it's beautiful when I see text on the screen.

I'm slowly seeing the merging of aesthetics where you have something that's visually attractive that also considers access. That's another reason why we decided to do Activating Captions—to show that artistry and captions, access, can come together. To me it's beautiful to have access to the conversations that are being held on screen—it gives me more information and allows me to interpret things.

SBIn an interview about Disarming Language, you both talked about ambiguity and directness in art and communication, pointing out the issues that come with ambiguity when it comes to making language accessible. Could you talk about how you're dealing with these questions of ambiguity and directness in both Disarming Language and Activating Captions?

NVTWhile thinking about communication around the two projects, we really thought about how to make our intentions as clear as possible. There is a conceptual framework, of course, which we respect and we don't hide, which is part of the structure of those projects—how they originated, were executed, and made visible to the outside world. We tried to make that as explicit as possible, which was a very conscious decision.

Our curatorial text about Disarming Language was really talking about the process behind it, which was unusual, because in a habitual curatorial text, you would approach it more theoretically or abstractly, and create a narrative, which hides the process. We tried to do the opposite.

With Activating Captions, we tried to be as clear and direct as possible with the project's intentions. Thinking about the notion of ambiguity is very interesting, because if you think about captions as access, which is a limiting way to think about captions, of course you're thinking about how to make things as clear as possible.

SBWhat comes to mind here is Carmen Papalia's Open Access, and this idea of mutuality and relationality, which corresponds to interpreting ambiguous and direct language through clear and open communication.

Activating Captions seems to expand on this idea of clarity by maximising it to the point of direct ambiguity.

Take a work like Carolyn Lazard's video A Recipe for Disaster, which explodes all the different forms of interpretation that are possible with a found clip: there is the found content of the video, the captions, the voiceover narrating the action, and the interpretive text that scrolls over as well as its narration.

NVTWhat's amazing about the work by Carolyn is that it also shows you something of the messiness of artistic practice and also the ambiguity and the complexity of it. So the project, even though it's thinking about access and going beyond access, also takes into account that things can be inexplicable.

What's so beautiful about the artworks in Activating Captions is that they really dismantle or deconstruct this notion of the caption as something that explains something for someone else to access it. It starts to fuck with that in a very productive way, and makes you question your preconceived notions about what captions are and what they can do and what they can be used for.

Non-English-speaking countries seem to be more receptive to captions and subtitles, and that is partly because most Hollywood movies are produced in English and people are used to them being subtitled. Now my stance is, if you don't like captions, I don't think we can be friends!

CSKI'll also comment on the direct part, and maybe not so much the ambiguity. As somebody who communicates in American Sign Language, it's not necessarily that Niels and I are working with two different languages, it's that we're working with a visual language through a spoken language. So there's a shift of modality, and the way that our cultures and concepts and ideas translate, also traverse modalities.

In my experience as a person with disabilities, what I've experienced is that I don't really have the ability or the privilege to be misunderstood, because if I'm misunderstood, that affects my access or my rights, or any other aspect of my life, so I have to be as clear as possible.

You have no idea how often I've wished for the privilege to be misunderstood. I've seen so many speakers being, and being able to be ambiguous and vague, and then the interpreters have to interpret that ambiguity or vagueness, and the interpreter has to make a decision about that.

Either the interpreter will take that information and pass it off to me and be like, 'Make your interpretation of that information', or they'll go even more abstract or ambiguous with their interpretation and I'll get even more lost. Often in my communication with Niels, we are a little more direct, saying, 'I like this, I don't like that, we're going to do that, ok'. And I do love that aspect of our communication.

NVTDo you remember when we were giving a curatorial tour in Tallinn when the exhibition just opened? It was a very complex situation where there was an interpreter and an Estonian Sign Language interpreter, so there were different levels of translation going on simultaneously. There were also deaf visitors.

That was a really meaningful experience, because at a certain point, I was talking about the relation to artworks in the space as a juxtaposition, and the interpreters asked if I could not use complex words like juxtaposition, because they're hard to translate, especially to Estonian Sign Language.

That was a very interesting moment, because I realised how much we rely on certain lingo. I think you can talk about complex things without using terms that already exclude a huge part of your audience from the conversation.

At a certain point, when we were writing our curatorial statement for Disarming Language, we decided to write 'disabled artists'—to phrase it directly. I think making the statement so explicit opened up a kind of confrontation within the text. That was a kind of activation we were thinking about.

We were also thinking of different ways in which the exhibition could be experienced by different people, without it becoming a fake anthropological curatorial position where you try to imagine how somebody else would experience something.

Disarming Language was done in a very spatial way; we were thinking about heights, the layers of the exhibition, and works running through other works. I remember Sunaura Taylor's text intervention that ran across the entire exhibition space and interfered with all the artworks as a kind of footnote.

Although Activating Captions has become an online platform, it has become the only way that I can imagine the project, because the different modes of access, resources, and discourse that surround the project can only be created in an online environment. It's not something that we could have created inside an exhibition space.

CSKNiels and I aren't a fan of online shows. Quite frankly, I haven't seen any that I like, and originally doing Activating Captions online was a second choice for us; we were hoping to do it in the ARGOS space itself. But then things changed and we were able to work with Eduardo Andres Crespo, one of the artists in the show, who also worked with us behind the scenes to create the website.

Eduardo is a person with a disability as well. Having the experience of working with someone who has a disability was different, and it saved us a lot of time, because Eduardo already knew what needed to be done and added his own insights as well.

For me, Activating Captions proved that online exhibitions are possible, and may even be better suited for video because it's already something that's on a screen.

SBThinking about the dynamics of transfer and activation, what have you learned from one another through your collaboration, and how has curating these exhibitions informed your practices?

NVTChristine is someone who constantly challenges your thinking, and that's why I respect and appreciate her so much. I tend to operate with a delay mechanism, and Christine is the one who jumps ahead while challenging whatever we are doing, which is super productive because it moves things forward.

I have worked with museum educators and as a museum educator myself, and I have seen how difficult curatorial work is. I have also encountered curators who were not very flexible because they were fixed to their own vision. But if you want to offer accessibility, it requires flexibility.

CSKLooking back, when I was offered the chance to curate with Niels on Disarming Language, I was hesitant to do that, and did not feel suited to the role throughout most of the process. But when it came to Activating Captions, I was like, we got this: we already have our relationship, our language, our dynamics, and our framework.

I deeply respect Niels as a curator. I've worked with a lot of curators, and done a lot of scheduling and writing that goes into curatorial work, which is not a passion of mine. But my relationship with Niels has encouraged me not only to challenge, but also follow up with the challenges that I've posed.

I still view my artistic practice and curatorial work as something that's separate, but when I put on my curator hat, I transform into the boss, but in a very different way, and I'm learning how to appreciate that.

SBAs a final question, I wanted to bring up what you both mentioned in relation to Disarming Language: that you don't subscribe to the idea that an exhibition can change people, but you think that it can encourage people to relate or think differently.

Christine, you've also said that you hope that the considerations in Disarming Language and Activating Captions might become part of an institution's daily practice, which makes these collaborative exhibitions feel like propositions for dismantling institutional ableism, in which the ableist perspective has become de-centred in order to expand frames of reference when it comes to ways of experiencing, sensing, and communicating through art.

How do you imagine such a future institution?

CSKI will say that my vision for the future for institutions and accessibility look like a person being able to walk into the physical space and not feeling any sense of anxiety. To me, that would look like a person being able to buy a ticket and not get stressed out.

Someone who communicates differently, they're already going to be stressed out about how to buy their ticket, because they're not going to be sure if they will be able to have that process go smoothly. They have to figure out whether they can get the text request, and whether they'll be understood. So they already have anxiety and they haven't even gotten to the exhibition.

For me, that process would be with ease, and even if they have an encounter with security guards or something like that, that that would be easy for them as well. Instead, people could walk into an institution and choose the experience they want to have, and that it could be in Spanish, for example.

I also want people to feel welcome. I know a lot of deaf educators are doing tours and guides in different institutions and do the work to make sure their audiences are welcome, but the truth is that a lot of deaf people don't feel welcome in institutional spaces, so they don't go. Making people feel welcome ultimately makes the institution accessible.

NVTSometimes I jokingly say that there are three spaces that are awkward to enter: independent record stores, night clubs, and art institutions. But there is also an appeal attached to that; that once you figure out how to move around in those spaces, they reveal a lot of secrets.

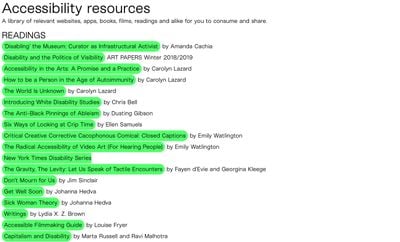

What Christine said is true. I've been referring my colleagues at ARGOS to this text by Carolyn Lazard, titled 'Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and a Practice', which is a really amazing document to activate thinking and different types of awareness about public programmes. There's still a lot of work to be done to dismantle institutional ableism. It's a long-term project.

Of course, we are funded by the government, and the government's speech is all about diversity. But we are not funded to make our spaces more accessible; we are funded on the bare minimum to make our institutions run on a day-to-day basis. But just recently, disability was added to the constitution of Belgium, so it's a major new step for the national context in which ARGOS is a part.

After a project like Activating Captions, we will have to consider how we are going to show an audiovisual artwork. It's a very slow, bumpy, awkward, difficult process, and it also needs to be done consciously, in the sense that it's not something that you can implement and suddenly everything goes smoothly. Though it might appear slow from the outside, we're committed to this process. There is nothing wrong with slowness.

One thing that covid has taught us at ARGOS is that we don't always have to produce something new. Sometimes we can take a step back and think about whether the thing we want to do is the best, or do we want to do something else?—[O]

[1] Exhibition press release, Activating Captions, ARGOS (6 April–8 June 2021), Accessed 6 May 2021, https://www.argosarts.org/event/activating-captions

[2] Exhibition press release, Disarming Language: disability, communication, rupture, Tallinn Art Hall (14 December 2019–24 February 2020), Accessed 6 May 2021, https://www.argosarts.org/event/disarming-language-disability-communication-rupture [n1]I might have said reactivate, but I think this is more correct.