Cindy Ji Hye Kim: Drawing the Unseen

Cindy Ji Hye Kim. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Nicolas Calcott.

Cindy Ji Hye Kim. Courtesy the artist. Photo: Nicolas Calcott.

In both medium and content, Canadian-Korean artist Cindy Ji Hye Kim has become expert at laying bare the tensions between the visible and the hidden, with artworks that often push the sculptural and performative limits of the traditional two-dimensional painting surface.

In her latest body of work, created for an upcoming solo exhibition at rodolphe janssen titled Riddles of the Id (12 May–18 July 2020), Kim gives the supporting elements of painting their own starring role in the traditional picture plane. For three of the presented works, including Riddles of the Id (2020), she has carved figures and objects into the stretcher bars, with two of those paintings also executed on silk organza. Presented off the wall, the silk organza paintings are illuminated by the light from the windows, the images on the stretcher bars—the silhouettes of ribcages, parental figures, and other objects melding with and complicating painted forms, such as vines and mice—cast onto the fabric's front-face.

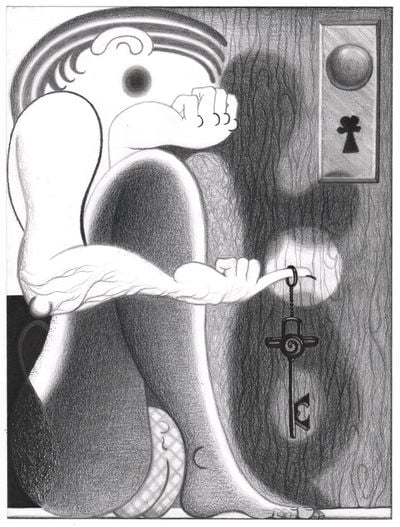

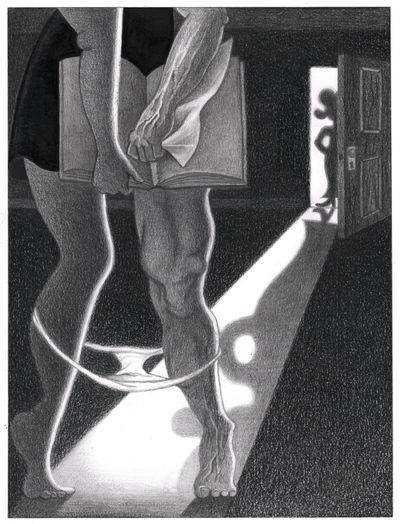

In this latest group of works, Kim also demonstrates a continued study of grisaille, a monochromatic drawing method traditionally utilised as an underpainting scheme from which an engraver makes a print, or in imitation of sculpture. Grisaille highlights the dream state of paintings such as Female Legacy (2020), an image rendered in charcoal, oil pastel and ink showing a woman's legs with her underpants pulled down to her calves in a dark room, whose cartoon-like quality pulls on tensions between innocence and experience.

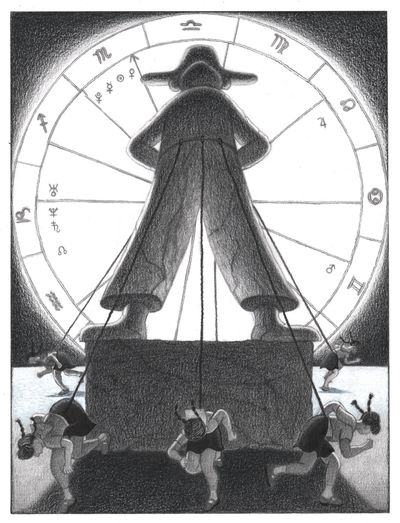

The characters Kim presents in Riddles of the Id belong to a recurring cast, which Kim first experimented with as an undergraduate student of illustration at Rhode Island School of Design, and then refined while a graduate student at Yale School of Art. These characters consist of a family triad formed of a man in a tall hat, a mid-century housewife-type, and a faceless schoolgirl, who populate the artist's ominous scenes as both physical and conceptual bodies. Kim has said that she imagines the man and woman—Mister Capital and Madame Earth, respectively—having birthed the schoolgirl; the three interact across tense planes of power and control, the parents looming as forceful authority figures while the child struggles between repression and desire. Using such dramatis personae, the artist embeds the muffled violence of waking life into heightened dream-tableaux.

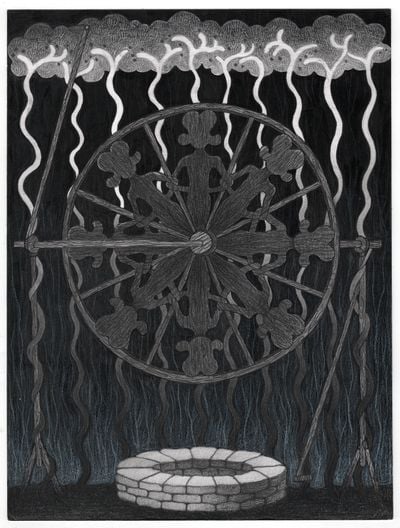

With compositions populated by archetypal characters, Kim's paintings appear potentially allegorical, yet no definitive moral conclusion ever fully comes to the surface in the artist's work. Instead, characters remain ensnared within the wheels of their tense scenes, with any opportunity for relief from corporeal and psychological chaos only leading further into the id's labyrinth. Recalling an unbreakable cycle, a circular motif serves to emphasise this feeling of entrapment in Reign of the Idle Hands #4 (2020), a circular canvas reminiscent of a phenakistoscope—a Victorian-era toy in which drawn figures on a circular piece of cardboard are animated when the cardboard is spun. But where the phenakistoscope should produce movement, Reign of the Idle Hands #4 is imprisoned in a single moment.

In this conversation with Ocula Magazine, Kim discusses the material and conceptual underpinnings of her exhibition at rodolphe janssen, and the spectre of violence that lingers over nature and individuals in conscious and subconscious realms.

CCThough they clearly all come from the same practice, each of your exhibitions seem to take on a very unique framework. How did you decide on the approach for Riddles of the Id?

CJHKI had just finished a large exhibition across two venues in New York back in September. It was an amazing experience, trying out so many different things—installation, paper-making, sculpture, et cetera—I really went all out. When the show ended, I had some downtime to just sit and think. After making a whole variety of things, I needed to reevaluate and parse out my visual vocabulary—to figure out what was actually important in my practice.

I've always loved this element of art: that it reflects the truth without claiming to be true.

One of the elements I wanted to focus on was the grisaille palette as a mode of image-making. Grisaille has historically been used as an underpainting technique, to be covered over with colour or discarded after its use. There's something feminine about that: a form that exists as a hidden layer. I wanted to charge this formal aspect of grayscale painting as a narrative component in my work.

I also wanted to further expand on the imagery of scaffolds and theatre sets, and how these temporary frames relate to the stretcher bars on the back of paintings. Both the grisaille palette and the stretcher bars are structural supports that usually don't get shown within a painting, and for the rodolphe janssen show I decided to narrow my attention to these two formal elements. In terms of imagery, I focused on the three characters that continue to reappear in my work—characters I sometimes refer to as my family.

CCThe id is often marked as the Freudian equivalent of the Jungian shadow. Shadows in those formal elements you mentioned, as well as conceptually, are a focal point in this latest body of work. Could you talk a bit more about how shadows play out in this show?

CJHKI like using the shadow as a metaphor in my work, because you can describe things without having to actually show them. It's an interesting framework to think about presence. To me, the act of erasing is just as important as drawing and painting when making an image, so I guess I was thinking a lot about this act of negation—of the absent and the unseen—when I was making this body of work. In the exhibition, I'm presenting my work as if I'm exposing the layers that are supposedly hidden: the underpainting and the stretcher bars. But what's important to me about these revealed layers is that they become yet another surface that produces shadows.

CCYour work recalls the duality of resonance and repulsion—how those two things operate individually, but also how they can so easily converge. Do you find these two forces influential to your practice?

CJHKThere is a constant pushing and pulling when I'm composing an image; I feel like I'm always stepping in and out of the picture frame, performing as a voyeur and a subject. To me, engaging with art is a rhetorical process. The duality of resonance and repulsion is an important element that influences my work.

CCYou previously worked for an animation company and also as a freelance illustrator—roles that are clearly visible in the paintings you produce. Are there other jobs or experiences that have influenced the direction or content of your work?

CJHKBabysitting was one of the jobs I had when I first moved to New York. I'm not a mother—at least not yet—or a teacher, so it's not like I interact with kids that much, but something about working with kids has always been mind-blowing to me. Maybe it's my paranoid mind, but kids seem to know so much more than what they show, and they're totally unaware of their capacity for truth. Kids are very open—they haven't developed this barrier to the world and themselves yet. I also think kids are very courageous in their vulnerability.

Being around kids in general is enriching, but when I was a nanny, I was witnessing these aspects of childhood in a heightened way. I think that plays into my narrative of the schoolgirl, but I've always felt this awe towards innocence. It's so rare to see it in myself anymore.

I studied illustration as an undergrad, and thinking back, I'm glad I have that foundation in terms of work ethic and craft—to know how to be observational and translate that literally through my hands. In grad school, I made a lot of installation and video pieces, which was ultimately a good experience: having tried, and failed, in so many different things.

There are a lot of people who have influenced me. While I was in grad school at Yale, one of the professors I studied with was Byron Kim, who is a minimalist abstract painter. My work looks nothing like his, but the conversations I had with him and how he viewed the world have very much resonated with me. Another professor was Rochelle Feinstein. Each of her projects has this quality that deftly moves through a constellation of themes. It's a kind of openness I'd like to have in my own work. Her general vitality towards life was at times very intimidating but nonetheless inspirational.

I think professors from both my undergrad and grad programmes shaped me a lot while I was in school, and I continue to see their influence play out since graduating. Sometimes being a student is like being a child who hears her parents giving sound advice, but doesn't listen and rebels, and then goes out into the world and realises, 'Oh, that's what they meant.' It's been about four years since I've been in school, but I still experience this pretty frequently.

CCYour practice seems deeply embedded in social dynamics, which are quickly changing, due to the coronavirus pandemic. Do you think this will have an impact on your approach in the future?

CJHKThe imagery I use in my work has mostly been set in a domestic environment, which is a place that's supposed to be safe. The current situation of 'being stuck at home' puts that in a different light. I think the composition of social dynamics largely depends on what kind of story we'd like to tell ourselves. At first, this pandemic felt like a classic 'man versus nature' kind of narrative, like Moby Dick, with an outside 'thing' coming to destroy us. But since that thing is an invisible virus that everyone is capable of possessing, often without even knowing it, and defeating the virus is not through some kind of heroic collective action but through inaction and isolation, the situation feels truly modern and contemporary—more like a 'man versus himself' kind of narrative.

In my art practice, I'm always trying to reconcile the real with the unknown, and to me, dreams play a crucial part in that dialogue.

This reminds me of the assignment I'm currently working on for The New York Times. They're asking artists to draw what they see outside their windows. It's an amazing prompt, because it's not really about what you see, but how you see through that window. Before the quarantine, I had a concrete division between the outside world and my private internal world. Right now, this dynamic feels very blurred, and I guess this shift in perspective will have an impact on my work in the future.

CCComing back to your use of the grisaille palette, in some of your earlier works you were still using colour, and though it appears in splashes in your exhibitions every now and again, you have for the most part left it behind. What initially influenced this decision?

CJHKIn the beginning, I just wanted to make better drawings. I've been painting in grayscale for quite some time now, and it started out as a way of taking my drawing practice to a larger scale. Drawings are like skeletons—a kind of hidden layer underneath paint that provides structure to the image. I was making all these drawings and realised, why should they have to be confined to the idea of being a sketch or a blueprint—an outline to be filled in with colour? I began to wonder why I had set up that rule for myself.

From there, I started using raw pigment, and turning graphite and charcoal into paint. I mostly paint in acrylic, so the approach of making my own paint was a way of transforming this plastic-y paint into pigment that sits on top of the surface, like the way charcoal sits on paper. It became an interesting formal challenge and investigation for myself, so I stuck with it.

To me, the act of erasing is just as important as drawing and painting when making an image

Once I limited my palette to grayscale, there was so much room for experimentation in terms of what I could do with texture, layering, and the nuances of different types of black, white, and grey. I don't think I purposefully abandoned colour; I just really wanted to get better at drawing.

When I think about working with colour—and I mean colour as in any pigment that falls outside of the usual grayscale palette—I mostly wonder what it would be like, knowing what I now know about paint, but that's where it stops for me at the moment. I think it's probably because I'm just really invested in the grisaille process for now. Colour is great, I love it—I love looking at colourful paintings, and when I look at the sunset, I think it's beautiful; but in my work, colour is another layer of realism that I don't currently need.

CCTwo of your most recent paintings take silk organza as their surface. What was the experience of working with such a surface in comparison to a more standard canvas or linen?

CJHKIt was a real challenge. I gathered a range of swatches of silk organza with different opacity and tautness. I ended up choosing ones that were on the thicker side, knowing that I had to stretch it and paint on it. When I was experimenting with the swatches, I noticed that the paint was seeping through the fabric in a weird way and looked uneven on the back. I realised that it needed to be primed with a resin-based primer, which would keep the transparency of the silk, but also form enough of a barrier between the paint and the fabric.

One of the pieces in the exhibition is painted on black silk. This was another challenge, because of the lighting situation in my studio. When I was working on this painting, I needed the lights to be shining directly from the back of the painting, so that I could see through the silk to align the painted forms with the stretcher bars. I ended up installing a spotlight behind the painting so I could match the image with the shadows that the stretcher bars had cast.

CCHow long did you experiment with these fabrics before starting on the final canvases?

CJHKIt took about a month. I made a few smaller frames to test the fabrics with. The edges of the fabric needed to be serged, so I had to find a seamstress who could do that. I stretched the silk myself, which was a very different experience to stretching canvas, so there was a learning curve to that as well. It took a while to find the right fabric and execute the paintings on it. There was a lot of preparation, especially because the fabric is very expensive—much more expensive than canvas—so I really wanted to figure out the right one before buying yards of it.

CCComing back around to this idea of shadows, the bodies in your works seem highly symbolic, like dream-state selves. Could you talk a little bit about this?

CJHKI'm so glad you mentioned dreams. The images of dreams are interesting, like shadows. I just started a dream journal, and I love the idea that something I can't face in my conscious life is, in a courageous way, manifested through the unconscious. Vice versa, I'm interested when something that I take for granted on a day-to-day basis takes a really perverse or unexpected turn in a dream. There's something so puzzling about it all.

For example, when a random person you have no feelings towards shows up in your dream and suddenly you can't look at them the same way anymore. For me, the body has a particular presence in my waking life, but then in a dream it becomes a cut-out or a puppet—just a conduit for a narrative.

In my art practice, I'm always trying to reconcile the real with the unknown, and to me, dreams play a crucial part in that dialogue. Dreams seem to emphasise the fact that I don't quite own my body, let alone control it, and that there's always a negotiation between my mind and my body. A dissonance between the two seems to me a fundamental human experience.

In my drawings and paintings, there's so much physical control over my hand and how I try to articulate these themes, but the process itself is actually very chaotic. I try to execute things as precisely as possible—to articulate what is essentially tumultuous and cannot be faced with reason. My hand ends up showing the futility of it all, and I think that's how I come to terms with my practice.

There is a constant pushing and pulling when I'm composing an image; I feel like I'm always stepping in and out of the picture frame, performing as a voyeur and a subject.

CCThat comes back quite nicely to the idea of the id—of the conscious and subconscious, and what feels like it should be, but is not necessarily in your control. Similarly, you mentioned in a previous interview not wanting to see the images you create, but needing them to be visible. Where do you mark this split between want and need?

CJHKWhen I'm making work, naturally, there's so much want. I'm ultimately the only one who knows and sees what I want out of my art. But during the execution process, I have to come out of that headspace and create a distance within myself and become the viewer. I think artmaking is a constant shaving of that want. If I can pinpoint when my work is successful, it's when it arrives not out of fulfilled desire, but at the moment of being overwhelmed. I think that point is when the real crux of art's power comes out, in a way, and maybe that's where the separation between wanting to see it and needing to see it occurs.

CCYou have talked before about your interest in tolerable violence, which can often feel more sinister than explicit violence. How do you choose your content, and how do you mark its limits?

CJHKI've always loved this element of art: that it reflects the truth without claiming to be true. I think a lot about that and the kind of expectations I have of art. This is an obvious remark, but violence is everywhere. I don't have to make a list of violent things, events of injustice, or painful experiences to make that point. The most I can do as an artist is to reflect that obvious aspect of life and distill it into a visible tension, so that it's not so obvious anymore. I try to find something through the personal dimension, but it's a far more difficult task to find the universal and particularise it. I often think about Balthus; in his work, everything is just on the edge. He never gives it all away, but he creates a very deft relationship to this edge.

CCAs a writer, I often mentally categorise various artworks as either prose or poetry—that is, I think about whether the work leans towards a more explicit narrative or prioritises the distillation of a feeling. What you've just said about taking these moments and refining them seems to place your work in the latter category.

CJHKI actually take so much more from writers than I do from visual artists. As a painter, I feel so chained by what I see with my eyes, but a writer can shift an entire situation with the fatal use of a verb. They can turn the entire world upside down with a simple gesture, which, to me, is so powerful.

CCThe paintings of Riddles of the Id feature no moving components, but time seems to remain a crucial element, from the clock motif to the use of natural light and the circular canvas' phenakistoscopic form. How does time operate for you in the narratives and the viewers' experiences of the work?

CJHKWith my illustration and animation background, I'm hyper-aware of the fact that painting is a static form. To me, that formal element of painting is not a given, but a lack. I don't see myself as a traditional painter for whom the surface is a field of accumulated material processes; rather, I try to explore image-sequencing and narratives unfolding in time in my paintings, kind of like seeing my images as frames within many frames. There's an element of blindness to that, and I try to make that part of my work. To me, the ability to only hold one particular scene is a strength in painting.

My approach to painting is very much based on trying to use what I have. I look at the architecture of the gallery space for each exhibition and ask myself, what are the variable elements, and what can or can't I control within the space? For the exhibition at rodolphe janssen, that approach was applied to the natural light of the gallery. There's one wall in the gallery that is entirely a row of windows. I wanted to make use of that element, so I gravitated towards using silk. I wanted to see the different intensities of the shadows of the stretcher bars in the painting as the lights change throughout the day.

As for the phenakistoscope painting, I like the idea that it suggests movement and time while remaining still. There's a pain in that. Trying to get at the narratives through such formal elements—through what the painting is—is always a crucial endeavour.

CCHow long have your family characters featured in your work?

CJHKThey first appeared in my work when I was an undergrad. I think it was around junior year. Even in graduate school, I made videos with my friends that featured these characters, but they didn't really start to come out explicitly in my work until about four years ago.

CCThe faceless schoolgirl is the only one who is known as faceless by virtue of her name, but we rarely see anyone's face in your images. In fact, the only face we really catch a glimpse of across Riddles of the Id is attached to the figure holding the key. Could you discuss this decision?

CJHKI want these characters to be as generic as possible. I'm sure whatever I consider to be generic is not neutral, but there's something about faces that's so recognisable and specific. I need these characters to be almost like bathroom signs—flat and anonymous. Faces are never empty enough—they steal the mystery away from the characters and occupy too much of the viewer's mind. So I made the simple decision to give the characters just enough markers of identity—like the hat and the hairdo and the uniforms—but not much more.

CCOf the group, the mother and father seem to uphold what is deemed the acceptable social order, while the faceless schoolgirl bears the brunt of this order and experiences a lot of tension trying to escape it. I feel like you're a novelist and I'm a fan trying to get you to tell me how the next book will end, but is it possible that she will, in some definitive sense, break free one day? In general, what's coming up next for this family?

CJHKI think we need to have hope that she will, but without the parents she would probably cease to exist, or become one herself. I'm a terrible novelist—I don't make plans for the characters in this way. Instead, I've cast them into these fixed roles: this is what they do, and this is what they look like.

CCOne does grow an attachment to her, and an investment in seeing her overcome her struggles. At the same time, returning to the idea of these characters as symbolic bodies, they are more like archetypes than real figures. Archetypes don't change—they're more or less stuck within the situations they were built to represent—so it does make sense that they can't exist outside of the struggle.

CJHKYes, and I think that's the magical element about archetypes: that they seem to be timeless yet outdated; recognisable but peculiar.

CCI already feel a sense of hopelessness looming, but can the titular riddles of the id ever hope to be solved?

CJHKI hope so! There is always a question of what these characters are going after. I think there's a meaning in their quest at least, regardless of the answer.—[O]