Climate Crisis: A History with Cooking Sections and Zozan Pehlivan

In Partnership with SALT Beyoğlu

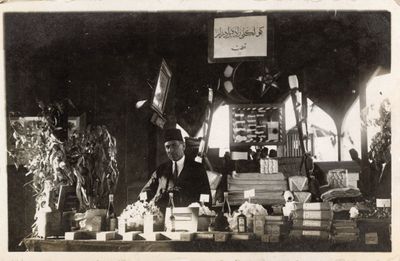

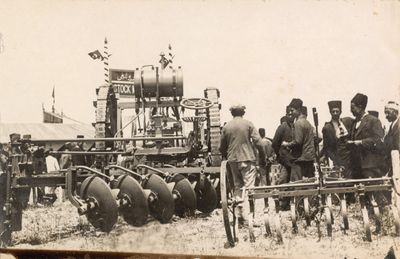

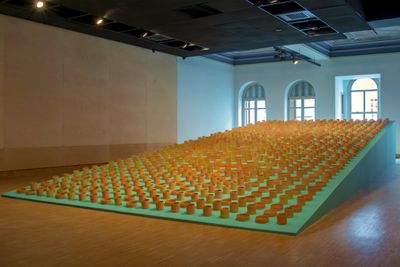

Cooking Sections, 2017. Courtesy Surface. Photo: Paul Plews.

Cooking Sections, 2017. Courtesy Surface. Photo: Paul Plews.

Consisting of Alon Schwabe and Daniel Fernández Pascual, Cooking Sections is an artist duo that uses installation, performance, and video to chart the role of food within geopolitics and ecology.

Nominated for the 2021 Turner Prize, the duo investigates some of today's most pressing environmental concerns. CLIMAVORE, the subject of their nomination, is a long-term project initiated in 2015 that examines the adaptation of food production within a 'globally financialised landscape'. Beyond the Eurocentric conception of seasonal cycles, Cooking Sections focuses on the effect of climate alterations on human eating patterns.

CLIMAVORE has been brought to areas suffering from water scarcity, including Sharjah, U.A.E, and Palermo, Italy, where the duo has developed micro-climates through research into drought tolerant plants as well as ancient cultivation techniques. Recently, CLIMAVORE has been based on the Isle of Skye in Scotland to work with farmers and restaurants to transition salmon farming from polluting methods to using filter feeders and seaweeds.

Salmon farming was delved into further in their project Salmon: A Red Herring (2021)—presented as part of Tate Britain's 'Art Now' series (2 December 2020–31 August 2021) along with the 13th Shanghai Biennale (Bodies of Water, 17 April–25 July 2021).

The performative installation examines the impact of the industry on Scotland's west coast, with run-off from farms causing widespread environmental damage. The deceptive pink colour of salmon, which is enhanced in farming with the provision of nature-identical astaxanthin—the tinted compound found in krill and shrimp—runs as a thread throughout, drawing attention to our changing perception of and relationship to colour, and, in turn, the planet.

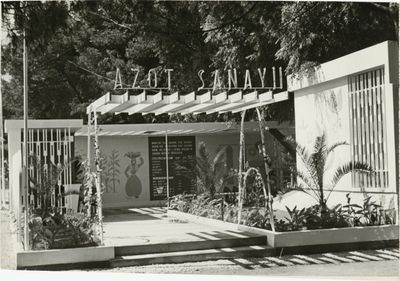

Cooking Sections' solo exhibition at SALT Beyoğlu in Istanbul, CLIMAVORE: Seasons Made to Shift (7 April–24 October 2021), brings together five research-based installations tracking histories of climate change in Turkey, where a 'climate, soil, and yield-based narrative' has dominated geography curriculum since 1941, though landscapes and yields have shifted drastically due to agricultural mechanisation and free market pressures.

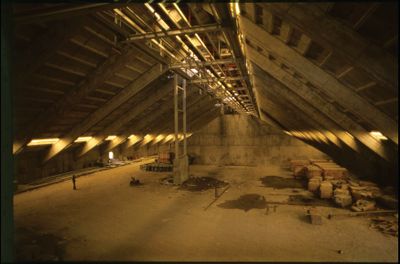

Departing from their presentation, which includes Weathered (2021), an archival display of plant matter in SALT Beyoğlu's cavernous entrance hall, Cooking Sections' Alon Schwabe and Daniel Fernández Pascual examine the social and political factors associated with climate change with environmental historian Zozan Pehlivan, who has studied the impacts of late 19th-century droughts and severe cold episodes in Ottoman Asia.

ASAfter Meriç Öner's beautiful introduction to the exhibition, we're excited to discuss how different elements and ecologies have shaped the material, financial, and agricultural history of Turkey.

DFPAs Meriç was saying, for us it was very exciting to go on this journey for two to three years with SALT's team, and to learn about these different challenges and how materials were recorded or impossible to record. Meriç also posed the question: what do we do when there are no archives? Or, when there are archives, how do we interpret them? Because often there are contested versions of the same story.

Zozan, your work was very inspiring for us in the making of Weathered. We'd like to jump into some of the writing you've been producing around Ottoman Kurdistan in the late 19th century.

Could you tell us what it was like to be a pastoral nomad at the time, and what climatic fluctuations characterised the environmental crises they experienced throughout the 19th century? Could you also elaborate on how you define droughts and extreme winters in that period?

ZPLet me briefly talk about what I mean by Ottoman Kurdistan. I think this is important in terms of geographical understanding. Basically, we are talking about a region that serves as a bridge between Anatolia—Central Anatolia and the Iranian Plateau. It spans the Caucasus, around Lake Van to Northern Mosul and Northern Aleppo.

It's a region that was inhabited by millions of people, including pastoral nomads and peasants. The approximate population was about two and a half million in the mid-19th century. Almost 60 percent of this population was agrarian, while about ten percent was urban, and 30 percent, depending on the region, were pastoral nomads.

I need to underline that this was an extremely diverse population. Armenians, Kurds, Turks, Arabs, Nestorian Syriacs, Jews, and Turks were living together in a very multicultural environment. It was not only theeconomy that was diverse, but also the society itself, in terms of ethnicity, religion, and language.

Even though we're talking about a period that seems to be very far away from us, I think this question resonates with the current moment, too, where we are facing a crisis that is similar—or maybe much,much worse.

What was it like to be a nomad in Kurdistan? I think one fundamental factor was mobility. Mobility is a fundamental issue when describing pastoral nomads in 19th-century Kurdistan. Mobility, plus being dependent on animals. Nomadic livelihoods depended on the existence of livestock.

Sheep, goats, camels, horses, mules: these were the basic types of livestock that herders or pastoralists owned. The necessity of grazing animals determined the dimensions of pastoralists' annual migration between southern and northern pastures. In the summertime, they would go up into the northern highlands, and in the winter, they would travel to lower pastures in the south to feed their animals.

My findings demonstrate that in 19th-century Ottoman Kurdistan, there were major climatic crises: four major droughts (in 1844–18 46, 1879, 1887–1889, and 1891–1893 respectively) and one severe cold event (1880). The interval between the first wave of drought and the second wave of drought was about 30 years, and the first one happened in 1845–1846 as climatologists have shown.

Although 150 years have passed since these famines, we still have the same unresolved questions in terms of their interconnections with infrastructure, pastoralists, relationships to the land and the landscape, and global powers.

A couple of weeks ago, two climate scientists Ünal Akkemik and Nesibe Köse were here and they described how climatologists found out about this series of droughts. After the 1840s, two back-to-back series of crises occurred in 1879 and 1880, and then during the 1880s and 1890s.

These crises were tremendous in terms of their consequences, which we can discuss. For example, when extreme, severe cold occurred in Mesopotamia in 1880, historical accounts and documents talk about the entire northern Mesopotamian plain being under snow for 45 days.

What happened to the millions of animals during this time? What about their pastures? Severe snow, storms, and winds affected this entire region and its inhabitants, both human and animal.

ASThe points about mobility, dependence on animals, movement through geographies, and how abnormal weather patterns influenced the life of people in the regions of Mesopotamia and the Ottoman Empire raise the question of who was better off. Who had a better life?

Throughout the early and mid-20th century, and more recently, there have been many accounts praising the life of the nomads as being more sophisticated and advanced, and better off in terms of the social, political, and economic structures they benefitted from.

We are living in a global pandemic. You can see how important the state is; the measures put in place by states in times of environmental crisisreally determine the direction of the crisis.

But at the same time, you argue in some of your work that it was the peasants who were doing better when it came to resisting environmental challenges. That brings up a really interesting and relevant issue.

Even though we're talking about a period that seems to be very far away from us, I think this question resonates with the current moment, too, where we are facing a crisis that is similar—or maybe much, much worse. We still don't know what the future holds.

So who had a better life between the peasants and the nomads in relation to this environmental change? Were the nomads less resilient to this extreme weather? How much does this reflect their ability to adapt to extreme weather?

ZPThat is a very good question, but also a very complicated one. It's complex and multi-layered. To begin, I think you have to understand the structure of agrarian and herding economies. A herding economy is basically an economy that depends on livestock, while an agrarian economy predominantly depends on land and agriculture.

In other words, pastoralists and peasants depend on different resources. That's one important thing. The second critical element is that, in times of drought, if you can keep your animals alive, this should provide a base to keep your livelihood manageable.

In terms of severe cold, however, animals cannot survive longer than a few weeks, and when the ground is packed with, let's say, one metre of snow, sheep or goats are not able to dig for food to survive. Furthermore, their bodies and immune systems cannot tolerate such low temperatures. So, they just perish.

Compared to droughts, pastoralists are more susceptible and vulnerable to severe cold, because their ability to feed their animals diminishes. This is another demonstration of the high dependency on animals.

When their animals perished, it was not possible for pastoralists to survive. This is a main point of tension. As you might have seen in Mongolia over the last ten years, 'dzud', or severe cold events, have killed millions of animals in Central Asia.

Abrupt changes in temperature have caused great loss among pastoralists' animals. So, who has the better life? I guess the answer is peasants. They have different resources, and more importantly, as we will discuss, they have the state backing them. The state is there for them. That is another critical factor.

DFPYes, that is one of the points we wanted to talk about, because it's crucial to these different degrees of vulnerability and dependency. How did the state, at the time, react or respond to these crises? The first crisis being environmental, and the second a social crisis with famine and the death of animals.

In our installation at SALT, we looked at reports from the time written in French in La Turquie, a financial newspaper that was gathering different accounts of how people and animals struggled to survive.

For peasants and nomadic pastoralists, they relied on spoken language, as you mentioned, such as Kurdish, Turkish, Arabic, Armenian, or others. In a way, there was all this activity happening, but it was also hard to record—so how do we learn about it today?

How have you dealt with the lack of written Kurdish historical documents in your research? Could you also speak about the different oral sources you have used, and state responses from the Ottoman administration? Who was making accounts of what was happening?

I think you also mention sources from European diplomats, merchants, and even travellers who were present in Ottoman Kurdistan at the time.

ZPLet me begin with the question of sources. If you're an environmental historian, you likely have multiple and extremely diverse sets of sources. One set would be scientific studies using, for example, climatologist findings or chronological studies.

You would also have studies from veterinary and animal sciences to help understand the immune systems of animals, their biology, and how they survive. What do they need, for example, under regular circumstances? How much water or food do they need to survive? How long can a camel survive without water, or how many days can a sheep survive without food?

So, on the one hand, we have the 'hardcore' sciences, like biology, zoology, and climate science—but as historians, we also have historical accounts and documents that we can interpret; where we can trace every little word, and the meaning of every little word in each archival document.

When I studied the history of this region, I used Ottoman and British sources extensively. I did not use oral Kurdish accounts because that requires a different historical methodology and a different historical approach.

In our installation, we are also looking at these patterns of migration and displacement that manifest because of different growing patterns, like the production of grain and the herding of animals in relation to the infrastructure that existed.

This doesn't mean that Kurds did not leave any accounts regarding climate or their environment or climatic circumstances. I only performed one search in the Ottoman archives. For example, there is a Kurdish phrase that says, 'It's not as cold as when the red snow falls.' I googled it and found nothing. I went to the Ottoman archive, and I searched for 'red snow', and I still couldn't find anything.

However, in European sources, red snow apparently occurred during the Little Ice Age. There was red snow, and it's visible in European paintings. And so we have this description of red snow, but in the Ottoman archives I couldn't find it.

While I did not use oral accounts, I did use extensive Ottoman and British sources. The Ottoman and the European sources demonstrate different mentalities. The European sources contain different explanations and understandings of the region, because they had many economic and political aims or projects, so they needed to understand the environment as well as society.

That's why we have really rich European sources in terms of geography, environment, and resources of the region. The British archives are especially full of these descriptions that explain, for example, which grasslands are most fertile, and what types of flowers or gall nuts are the best in which part of the region, and so on.

Unlike the British colonial administration in India, which abolished the traditional granaries that were keeping South Asians alive in times of environmental crisis, the Ottomans reserved their granaries for times of starvation. They supplied cities, especially administrative and commercial centres like Diyarbekir, Erzurum, and Van.

They prohibited the exportation of any grain or animals, such as dates, figs, any type of food, and even straw. They prohibited the exportation of these goods. They also lifted tariffs on customs, so merchants could actually import grain and supply the population.

But this doesn't mean the Ottomans were perfect and the British were evil. As historian Özge Ertem has shown, bread riots were very common in different parts of the empire, especially in Diyarbekir. There were massive rebellions in times of crisis, such as the bread riot of 1880.

ASThis is a really great point, and you're demonstrating how two things were happening at the same time. On one hand, we have the world becoming more globalised through empire and the different empires that operated at the time, and the massive trade in agricultural produce and the infrastructure that it required.

At the same time, we also see the manifestation of famine—how it was engineered, and how certain populations were sacrificed or protected in different periods by different political regimes and different governments.

How did the state, at the time, react or respond to these crises? The first crisis being environmental, and the second a social crisis with famine and the death of animals.

In our installation, we are also looking at these patterns of migration and displacement that manifest because of different growing patterns, like the production of grain and the herding of animals in relation to the infrastructure that existed.

As you touched on, the Suez Canal completely diverted trade from the Tigris towards the Red Sea, which enhanced the maritime trade that was already taking place. That opened up the Mediterranean and shortened the journey to Europe.

In this context of 19th-century globalisation, how did the Suez Canal actually worsen people's livelihoods in Ottoman Kurdistan? This was a region, as you put it, that was relatively stable, yet later descended into the violence of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Are there any parallels or equivalents you can draw that are related to more recent infrastructure, and the bigger building projects that have taken place in the region in recent years?

ZPAgain, this is a big, multi-layered subject, with many different sides to the story. For global trade, the opening of the Suez Canal and the establishment of railways was a gift. A gift that sped up the flow of goods and people from Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean.

So let me start with the story of infrastructure and railways. The railway came to the Ottoman Kurdistan very late. Unlike Western Anatolia, Kurdistan's railway developed at a much later period.

In Western Anatolia, historian Onur İnal's study has shown that nomads integrated themselves into the construction of the railways by providing timber. These groups possessed the knowledge about areas they had inhabited for centuries. As such, when railway projects came to the region in the 1860s, they integrated themselves into the system.

In Kurdistan, we don't see these same experiences with the railway, but we do see them with two major changes: steamship technology and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.

When certain flows change or certain ports and canals open, these events reorganise multilayered systems, the results of which can be bothpositive and negative. That's also crucial to our own work.

The opening of the Suez Canal affected Kurdistan both directly and indirectly. In terms of direct consequences, we see a shift in the volume of trade. Before the Canal, a large portion of trade from South Asia to the Mediterranean world was passing through the Persian Gulf, Iraq, Kurdistan, and Syria.

Pastoralists carried goods from the Port of Basra in the Persian Gulf to Aleppo then onto Alexandretta. Their camels served as contemporary railway tracks. They would carry goods through the desert route, or theywould travel across Basra, Baghdad, and Mosul and then further north toKurdistan.

When the Suez Canal opened, this entire trade system began to lose importance. That's one consequence. On these long-distance caravan routes, pastoralists also provided certain services and goods along the route. For example, if five camels died or starved to death in a merchant caravan, pastoralists might have sold new animals to the merchants.

When this trade was disrupted by the opening of the Suez Canal, their income began to diminish, and this diminishing income had certain consequences for their welfare and for their social wellbeing.

Another critical consequence of the Suez Canal's opening is that pastoralists lost revenues and income when Beirut became a new, central port city, while Aleppo, which served as an entrepôt for centuries, began to lose its economic importance.

If you look at the history of this region, Ottoman Kurdistan was more integrated with Aleppo and Mosul than Trabzon or Ankara. So, Aleppo's waning trade importance affected Kurdistan and pastoralists in different ways.

DFPThat's something we are really interested in. When you look at climate, you cannot separate all these different factors. Of course, there are severe droughts and winters, but it's all interconnected in terms of disruption.

When certain flows change or certain ports and canals open, these events reorganise multilayered systems, the results of which can be both positive and negative. That's also crucial to our own work.

Could you connect these occurrences to more contemporary conditions? The whole region has shifted tremendously over the past century or more in terms of weather events, transformations in the landscape, and the rearrangement of borders between different countries.

How many people do you estimate practice transhumance today? Are there people still moving across the region, to winter or summer pastures or even across borders with their animals? Are there any new climate threats?

This is all part of the conversation that people are really struggling with at the moment. All in all, how do you see the future of nomadic pastoralism in the region?

ZPLet me start with this idea of how global climate change and global warming are going to affect this historical form of subsistence. I don't have the exact number of pastoral nomads left today in Turkey's Kurdish environment. It wouldn't be an exaggeration to say approximately 50,000 to 100,000 people.

Some are partial or seasonal nomads, because they stay put in villages or communities in the winter, and in the summertime, they travel to their pasture lands. Global warming is a threat to all remaining pastoral populations from Central Asia to Syria; Eastern Anatolia to Siberia; and Central and South America.

It is a global threat because it affects water resources and pasture lands, and it causes major disruptions in temperature. That's one thing. The second critical thing is economic development that costs lives. Dams and mining projects are major threats to these historical forms of subsistence.

In Turkey, there are two fundamental threats to pastoralists' subsistence. One is the politics of coercion that puts restrictions on access to natural resources, like pastures, which basically prohibits pastoralists from accessing their traditional pasture lands by declaring these lands military zones.

This affects them tremendously. Their animals get weak, and they become susceptible to disease, or their fertility rates decline immensely. The products that pastoralists harvest from these animals, like dairy or meat or wool, greatly diminish as well, because they all depend on access to pasture lands.

So, as we talked about earlier, we can see the role of the state in relation to the environment. Political decision-making has real implications in terms of forms of subsistence. In my own work, I introduce the term 'ecological instruments' to try to convey the intentionality of this relationship: state interventions to the environment are not neutral.

We have to re-establish a lot of these linkages and ecological tools that have been completely eroded by state and corporate practices.

The second critical threat for remaining pastoralists, globally, is that they practice the most humane and sustainable form of meat production. The disappearance of nomadic pastoralism around the world will limit meat production and dairy production to animal farms, which are extremely inhumane and unsustainable.

The historically close relationship between humans and animals will be reduced to the exploitation of animals, where they are just giving us meat and milk. It is an ethical issue. The entire relationship between humans and animals is transformed. I think that is a major threat that we need to consider.

The disappearance of nomadic pastoralism around the world will limit meat production and dairy production to animal farms, which are extremely inhumane and unsustainable.

ASThat is an incredible point that is extremely relevant today when we're thinking about food production and the climate emergency, and how it's our duty to reconnect food practices to the lands, and reconnect food consumers to ways of growing. We have to re-establish a lot of these linkages and ecological tools that have been completely eroded by state and corporate practices.

You are touching upon something at the core of the work that we developed for the exhibition. Maybe you can tell us about the book project and your plans to advance this research?

ZPIn my book monograph, tentatively entitled Before the Genocide: Pastoralists, Peasants, and Environmental Crises in Late Ottoman Kurdistan (1840–1914), I examine the implications of climatic anomalies that occurred in the 19th century. I look at the impact on agrarian and herding societies, and how their communal relationships were affected by these crises.

I look at social tension, confrontations, survival strategies—and the last question I'm asking is: where is the Ottoman state? Where should we locate the Ottoman state in politics and in the entire environmental crisis? How was the state involved in this process? What type of responses did the Ottoman state develop? These are the major questions that I'm raising and responding to in my book.

...on the one hand, we have the 'hardcore' sciences, like biology, zoology, and climate science—but as historians, we also have historical accountsand documents that we can interpret; where we can trace every little word, and the meaning of every little word in each archival document.

We are living in a global pandemic. You can see how important the state is; the measures put in place by states in times of environmental crisis really determine the direction of the crisis.

This also applies to the implementation of certain policies, like situating vaccination sites and the way a state distributes vaccines to every part of the country, or by supporting scientists to work on vaccines, and so on.