Daniel Arsham

Daniel Arsham. Photo: Joyce Yung. Courtesy Galerie Perrotin

Daniel Arsham. Photo: Joyce Yung. Courtesy Galerie Perrotin

Daniel Arsham arrives in Hong Kong from New York in time to enjoy the last four hours of his birthday, although with his new show, Fictional Archeology, about to open at Perrotin in Hong Kong, there is little time for celebration. In fact, with exhibitions on three different continents in the next month, he may have to put the morning-after hangover on hold for a while.

Cleveland-born Arsham has all the hallmarks of a 21st century Perrotin pop-artist: young, cool, and with an Instagram account boasting encounters with other young celeb creatives—like fellow Perrotin artist JR and singer Pharrell (with whom Arsham has collaborated), stars like Juliette Lewis (who he cast in a short film), and art world dilettante, James Franco.

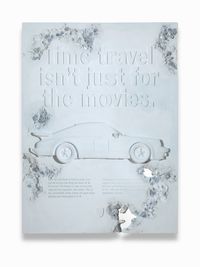

He made a name for himself by playing around with monochromatic sculpture castings that confounded and challenged our expectations and understanding of space: white figures seemed to push out of walls, or emerge out of the floor. Later he took everyday objects like cameras, radios, film projectors, guitars, and eroded them, making them look like artefacts from our time dug up by archeologists in the future.

Arsham's superclean white-on-white aesthetic has translated well into almost any other creative field and medium, as attested to by his string of multidisciplinary creative collaborations: he has done stage sets for Merce Cunningham; a book for Louis Vuitton; keyboard sculptures with Pharrell; and has worked on a bunch of architectural projects with Snarkitecture, an architecture-design practice he set up in 2005 and co-runs with a friend out of his studio.

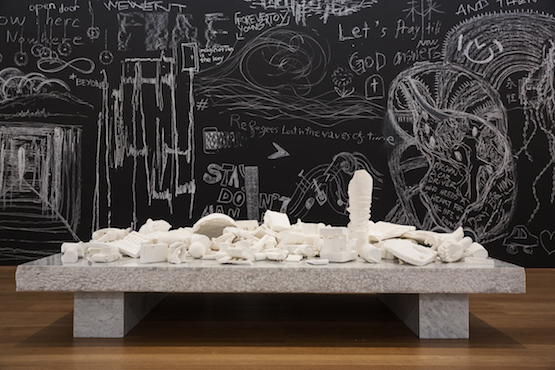

The space of Perrotin in Hong Kong looks like it's temporarily hosting the archeological preserved remains of Pompeii. Arms, hands, and bodies, in archetypal postures of classical sculptures, dissolve into, or emerge out of the wall. A figure sits in the middle of the gallery space crystallised halfway between falling down and standing up, frozen somewhere between destruction and reconstruction. A black wall stretched across the back of the gallery features white scribbles and doodles, resembling a classroom chalkboard sabotaged by the students.

The work, titled The Future Was Written (2015), is a participatory installation included as part of the exhibition. Composed of a marble pedestal laden with chalk fragments—hands, fingers, phones, radios—and a blackboard, visitors are encouraged to add their messages with the white chalk fragments. On the day I visit, bleak messages are scrawled across the chalkboard by students. It is quite fitting for an exhibition that on the surface appears dystopian. We chat with Arsham about his new show on the eve of his Galerie Perrotin Hong Kong opening.

DDAYou refer to yourself as an "archeologist from the future". How did this idea of fictional archeology come about?

DAA couple of years ago—2011—I was in Easter Island—I was there making some paintings which were gathered together for a book. I was just watching the archeologists work, and I started to think about the kind of fictional nature of archeology. You know, in that inherently there's no way to determine exactly what occurred. So they're tasked with creating a story out of objects. So if we can project into the past in that way, could I find a way of carrying that into the future as well? So when I returned from that trip I began making works that are contemporary objects—cameras and phones and things like that—which were made of geological materials, like volcanic ash, crystal, that convey this sense of time.

DDAIs this how these objects were made—it's compressed volcanic ash and bits and pieces?

DAExactly. So I get the ash into the studio and it's compressed into a very fine powder. You can see in some of the works, the detail is very pronounced. The coarser area, where you find some erosion, is the way wax is used in the moltening process and it reacts with the binding elements and those areas fall away.

DDAThe figures seem quite gestural, and there are a lot of hands in gestures protruding from the walls as well. Is there a historic or symbolic meaning behind the gestures and figures you use?

DAThe figures are related to a couple of ideas. One is, there are these very famous figures from Pompeii that were calcified in ash, and, when we look at sculptures from antiquity it's very rare that they find entire figures, right? They'll be legs missing or arms missing. Often they'll recompose those areas. Sometimes when you go to museums you'll see a display underneath which shows the areas that were found and the areas that were reconstructed. So some of these works were made intentionally with areas missing. The crystal in them, and the idea of geological materials in them allows them to float somewhere between falling apart and growing on. You have the sense with the figures with the crystals in them that they almost could join at a certain point.

DDAYou have said that architecture and its overarching themes are woven into your practice. I'm interested how you've used architecture as a tool and concept in the show?

DAI think the work that engages the most is the work with the chalk. It's a slightly different concept from the rest of the works but all of those pieces are constructed from chalk—they're cameras and phones, microphones, and things really related to communication. Through the process of people coming in and writing on the wall, the pieces are destroyed. This idea of communication is transferred, but through that transference the works become dust, essentially.

DDAThe messages [written by students on the wall] seem bleak. Was there direction from you?

DAThe only direction I gave was to draw something related to time. There are a lot of disaffected youth in Hong Kong ... you know, with the recent protests ...

DDAThroughout your practice you've used a monochromatic colour palette. Is there a reason for this choice?

DAI'm colour blind, so part of it when I use that tonality, I know what I'm seeing and experiencing is the same thing you do because of the lack of colour. It's also a very simple idea of not altering materials. The reason the black works are black, is because the volcanic ash is black and the crystal is white. So there's a kind of truth to the materials. When I make works that intervene in the architecture, the reason they're white is because the walls are white. So, there's a kind of focus and reduction that can happen through that. I feel like I'm making things without really adding anything. I'm using something that already exists. It's a transformation of that thing rather than a reinvention of it.

DDALet's talk about your film. You've worked on a lot of collaborations with many creatives. Can you talk a little about the Future Relic films and why you ventured into that? The films seem to be covering similar themes.

DAYeah they are. I've been working in film for a while now. Film for me encompasses all the things I'm interested in—architecture, performance, sculpture, and photography. But it started really because people asked me questions about the work I was making, you know "What is the universe you're creating?" "What is the world in which you think these post-apocalyptic objects exist?" For me it wasn't a negative; I wasn't imagining this dire world. So I wrote a treatment for a film, and because I happened to know some people who worked in that field I kinda jumped into it. It's definitely a learning experience. The film, Future Relic, was nine different parts. I wrote four of them so far.

DDAI'm not sure which one I saw. There was a talking owl that could speak Japanese.

DA[Laughter] That was the third one. The fourth one is coming out in December in Miami.

DDAIs there a linear narrative to it?

DAYes, the stories are all linked actually, although it feels like they're very disconnected. The story jumps around in time, but in the end it will all make sense.

DDAIs there anything else you want to explore creatively?

DAI'm continuing to work in stage design. I worked with Merce Cunningham. That was one of my first jobs, working on stage design for Merce. I'm continuing with the films. That feels like the largest gesture I can make right now, and engages so many creative people who know how to do things I don't know how to do right now. And they're very good at it. —[O]