Dawoud Bey: Remembering Louisiana and the Mississippi River

In Partnership with EXPO Chicago

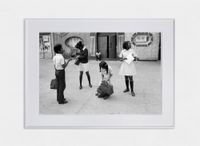

Dawoud Bey. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly.

Dawoud Bey. Courtesy the artist and Sean Kelly.

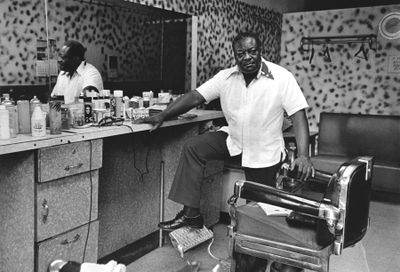

Dawoud Bey began his career as a photographer in 1975 with a series of portraits of the Black community in Harlem, allowing the former Queens-based artist to get in touch with the neighbourhood where his family lived.

'The relationships and exchanges that I had with some of these people are experiences I will never forget,' the artist explains. 'It is in those relationships and the lives of the people that these pictures recall that the deeper meaning of these photographs can be found.' Titled 'Harlem, USA' (1975–1979), the series marked the beginning of Bey's engagement with people to shed light on different contexts and histories.

From 1988 to 1991, Bey expanded his portraiture to different cities in the U.S. with the series 'Street Portraits', framing African-American citizens in different contexts with a large-format camera using Polaroid film, mounted on a tripod for formal precision.

Both a photographer and educator, Bey is deeply invested in the history of photography, integrating into his practice references that span the medium's genesis to the present moment. Teaching at Columbia College since 1998, among his first students were Carrie Mae Weems—now showing work alongside Bey at the Grand Rapids Art Museum in Michigan (In Dialogue, 29 January–30 April 2022)—and Lorna Simpson, all of whom were part of a community of photographers helmed by an older generation including Jules Allen and Frank Stewart.

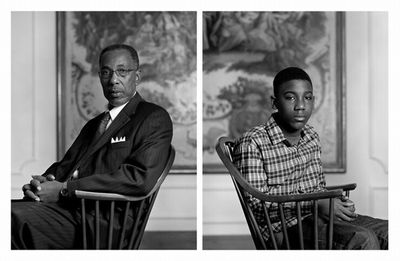

In recent years, Bey has looked at how trauma and history are registered through photography, engaging with the landscape tradition alongside his work in portraiture. The first of the artist's three historically informed bodies of work, 'The Birmingham Project' (2012), takes as its departure point the white terrorist bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama by Ku Klux Klan members, resulting in the death of six Black children.

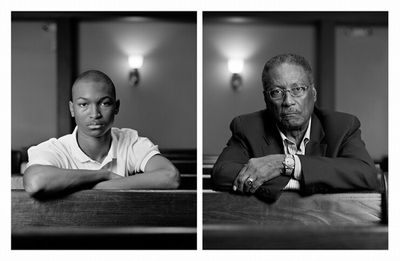

For 'The Birmingham Project', commissioned by the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, Bey created 16 pairs of photographs, each containing the portrait of a child of the same age as the child killed in the bombing, along with an adult of the age the child would have been in 2013.

The decision to collapse different generations into each diptych originates from Bey's desire to expand the notion of the still-image to reflect the lasting impact of past events. Such is the effect of his latest historical series, 'In This Here Place' (2020), which presents landscapes in Louisiana—locations in which the history of enslavement still hangs in the air.

The series was most recently exhibited in the artist's travelling retrospective, which began at the Whitney Museum of American Art (17 April–3 October 2021), followed by Sean Kelly in New York (In This Here Place, 10 September–23 October 2021), and is currently on view at The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (6 March–30 May 2022).

Transcribed from a talk during EXPO CHICAGO (7–10 April 2022) as part of the fair's /Dialogues series, Bey joins Sarah Meister, executive director of the Aperture Foundation, to discuss how African-American history is embedded in the American landscape, as well as his key influences and concerns.

SMI first got to know Dawoud's work when I was at MoMA, where we did a major acquisition featuring some of the work that we're going to talk about tonight. Now I'm at Aperture, where Dawoud is a trustee, so I'm getting to know him in new ways. His leadership at Aperture is deeply appreciated.

Dawoud, you have many exhibitions happening this year, including at the Grand Rapids Art Museum with Carrie Mae Weems right now, and a travelling retrospective on view at The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. How are you doing?

DBIt's been an extraordinary opportunity to have these exhibitions, but I think I'm allowed to say that I'm a little tired. I'm glad to be here and to see all of you come out to show your interest in the work. It's why I do it, after all.

I need to make the work that I want to see—the work I need to see, but also to provoke conversation. If the work stayed in my studio, it would not be fulfilling or meaningful to me.

SMWhat is your relationship to Chicago?

DBI came to Chicago in 1998, five years after a residency project in 1993 with the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College. Some of you may know I've been teaching at Columbia College since 1998.

My brother and his family were living in Chicago, so I was initially familiar with the city through that. But the residency project was my real introduction to the city and its art community. It was a direct outgrowth of that exhibition that I began exhibiting there, initially with Rhona Hoffman Gallery for many years, and now with Stephen Daiter Gallery.

In 1998, I was contacted by the then director of the Museum of Contemporary Photography who told me there were two positions available in the Photography department.

SMDid you get to choose the position you wanted?

DBYeah. And it's not coincidental that I was contacted by a museum director for a position in the Photography department, given it was when my relationship with museums began.

You occupy a unique position, as an educator, artist, and leading voice in the field. When did you realise you were going to be a teacher?

Well, I think I became a teacher for the first time in 1976 or 77.

SMPretty early.

DBI was contacted by The Studio Museum in Harlem, who invited me to teach a photography class there.

At the time, The Studio Museum had an active programme of classes and workshops, including photography classes, and I became a part of that community. Some of you probably know director and filmmaker Julie Dash, who took a film class there. Studio Museum was hugely important in the initial formation of my community.

One of my first students is now my dear friend Carrie Mae Weems. She walked in with her camera in hand. She was shy. She asked me, 'Do you think I could be a photographer?'

That's when I became a teacher—when I realised the importance of supporting someone who believes that you have something to teach them. I answered what I thought could only be the right thing, 'Of course you can. Let's get to work.'

SMThat's a really interesting moment, because just yesterday we were talking about your first exhibition at Benin Gallery—Ed Sherman's gallery in Harlem in 1976—with Frank Stewart and Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe.

You described these artists, whom you felt were much more sophisticated in thinking about themselves, as photographers. Can you take us back to this moment?

DBI was the younger one within that community, maybe by a decade or so. Of course, they became my mentors and then my friends.

Frank, Jeanne, and Jules Allen are about seven years older than I am, and they had all graduated from Cooper Union. The only ones who were the same age were me and Carrie Mae, so we were between older and younger photographers. Carrie Mae and I were kind of straddling that divide and had deep connections to both the history and younger photographers like Lorna Simpson, who were starting to emerge.

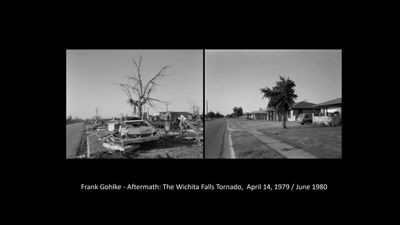

SMIn the slides for this talk, you included three works by other photographers, including 'Aftermath', Frank Gohlke's Wichita tornado series from 1979 and 1980, which is an interesting starting point into the discussion of landscape.

DBFrank Gohlke, who was my advisor in grad school, was one of the first photographers whose works within the landscape tradition were dealing with this aspect of making photographs in the now and then.

He photographed the Wichita Falls tornado as it took place, and once again the following year, which expanded both the notion of time within the still photograph, and how to make the still photograph extend beyond the moment it was made.

Although I had no interest in engaging with this tradition at the time, the work made an impression on me. I got to know Frank well, and I was able to have conversations with him about his work, with no inclination for it to become a part of my own work.

Joel Sternfeld, who also was one of my advisors in grad school, in the Yale MFA Photography programme, his photographs are from this project 'On This Site' (1993–1996). There is no text with the pictures here, but there is a textual component to this work as well.

Gohlke's work deals with this aspect of past and present within the singular photographic presentation. While photographs from 'On This Site' were taken where horrific or traumatic incidents happened but are no longer visible, yet still very much a part of the narrative of that site.

I'm from New York, and grew up as the two events in these pictures took place. One was a young woman who was raped in Central Park, at the site in the photograph on the left. It became known as the 'Preppy Murder case', because the assailant, Robert Chambers, was a very Upper East Side, preppy young man of privilege, and he had strangled a young woman to death after luring her into the park.

On the right, is a photograph of a site that represents a transformative moment in culture. Made in Forest Hills, Queens, it is where Kitty Genovese was raped and murdered. It was later found that 38 people heard or witnessed the attack happening, but no one did anything. It represented a shift in the culture, a kind of growing social disconnect, and apathy.

All these photographs by Sternfeld are places embedded with history—a narrative that has attached itself to these places, and are very much a part of their meaning.

I read something by Pete Hamill in his book Downtown: My Manhattan (2014), where he talks about his life growing up in New York. He came to the conclusion that the deeper meaning of every place lies, as he describes, in what it was and what it is. And that idea stuck with me.

These Sternfeld photographs evoke that idea—that you can make a photograph that evokes the memory embedded within the landscape.

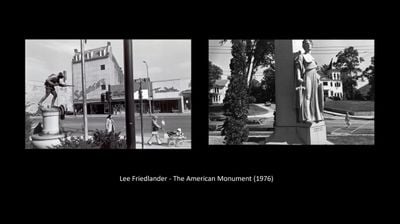

Finally, we have Lee Friedlander's epic project, The American Monument (1976). He went across the country photographing monuments, revealing the fact that we are surrounded by markers of history that we become ambivalent towards, over time.

SMOr blind.

DBYeah. The past is being memorialised in our contemporary moment, and my work is made to be a part of that conversation.

I'm also making work in places and different landscapes that are deeply embedded with aspects of African-American history—photographing these places to bring them into a contemporary conversation.

SMEach of these examples are so interesting because they require—not unlike your series—different amounts of information to know what you're looking at and why it matters.

One of my last projects with MoMA was a Dorothea Lange exhibition (Dorothea Lange: Words & Pictures, 9 February–19 September 2020). Lange said that all photographs can be fortified by words, which I found to be a curious statement for someone who dedicated their life to making images.

I disagree with it, actually; I don't think all photographs can be fortified by words.

DBThey can be. It's an option.

SMIt is an option. Although I think, like with Lee Friedlander, they don't require words the way Joel Sternfeld's photographs do. For people who did not grow up in New York and didn't see the site of that murder case on the front page—and I remember it very vividly, as well—some photographs really are helped by words to guide their understanding.

That could be a good way of entering into discussion about some of your works, starting with 'The Birmingham Project'. What do you expect or hope that someone brings to these pictures?

DBThis work is anchored and motivated by the tragedy on 15 September 1963, when four young African-American girls were killed in the dynamiting of the 16th Street Baptist Church.

Later that same day, two young African-American boys were killed in related acts of racist violence. Six young African Americans were killed that day.

SMWhat brought you to Birmingham and made you want to photograph this site?

DBIt was something of an epiphany. In 1964, a book called The Movement: The African American Struggle for Civil Rights was published. It is a book of photographs of and about the Civil Rights Movement, published by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

They had given these photographs—of demonstrations, police violence, lynching; all related to the Civil Rights Movement—to Lorraine Hansberry, the writer and playwright, and asked her if she could write a text that would weave these images together.

My mother and father went to hear James Baldwin speak at the church that I grew up in, and after his talk, they were selling this book. It was published as a fundraising vehicle for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

I'm very deeply based in the tradition of photography, all the way back to Louis Daguerre in the 19th century and up to the contemporary moment.

My parents bought the book and brought it home. I was an avid reader; they knew that if they left it in a conspicuous place, I would read it. So I started looking at it, and there were a number of really horrific photographs.

One, in particular, was of a young African-American girl, Sarah Collins Rudolph, laying in a hospital bed with two heavy gauze bandages covering her eyes—that picture seared its way into my psyche.

I would have nightmares about that picture sometimes. Eventually, I was able to park it somewhere in my subconscious, and stopped thinking about it.

Many years later—a good 40-plus years later, something shook that picture loose. I woke up one morning, bolt upright, as if someone had slapped me at the back of the head, and that picture came flashing back.

I needed to do something, so I went to Birmingham to see the place where this trauma took place, because obviously, I had not forgotten. I didn't know anyone there, but I intended to attend a service at 16th Street Baptist Church to bear witness to that place.

During that first trip, I had some very enlightening conversations I did not expect to have—not everyone, including the minister of the church, was as interested in revisiting that history as I. That was the first realisation that Birmingham's relationship to its own history was complicated.

I thought about making portraits of young African Americans in Birmingham, of the ages of the six young people who died. But that felt incomplete, because it didn't address the passage of time, the loss of possibility, and making photographs that speak of the past and present simultaneously.

I decided to not only photograph young people, but older people in Birmingham who were the same ages those individuals would have been had they not been murdered that day. To put them together—an 11-year-old girl with a 61-year-old Black woman—I would be able to talk about the passage of time; the loss of possibility, absence, memory, and the 50 years that have passed since that tragic moment.

I could make the photographs function in multiple ways, and resonate in a way that brought what I thought was sufficient and meaningful weight to this trauma. There are 32 pictures, 16 pairs or diptychs.

SMLast autumn, they were shown at the New Museum, in the exhibition Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America (17 February–6 June 2021), which was originally conceived by Okwui Enwezor. They are also in your touring exhibition, and on view at Sean Kelly.

DBYes. I showed 'The Birmingham Project' at the Birmingham Museum of Art (12 September 2018–22 April 2019), almost exactly 50 years to the day of that incident, because I wanted the work to be seen in the community and the context in which the incident had taken place first.

SMThe conversation around your work extends beyond museums and galleries, even though they are the places where it's easiest to see them.

Let's move on to the second series, 'Night Coming Tenderly, Black' (2017). How did you get into this body of work? It takes a very different look at how trauma and history are registered through photography.

DBThe Birmingham work was the conceptual turning point, where I began wanting to engage more deeply with this idea of the work being about the past, but in a contemporary moment, in a way that created a kind of liminal space. It was foundational to the history projects that came after.

In 2018, I was invited by FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art to make work. I had just completed 'The Birmingham Project', and knew I wanted to continue to make work about history, so I decided to research African-American history in Cleveland, Ohio.

I quickly realised the important role that Cleveland and northeastern Ohio played in the underground railroad—the path of fugitivity for enslaved African Americans who had taken on their self-liberation by way of the underground railroad.

Again, all of these are fact-based projects that were meant to trigger my imagination, as I began to think about how to visualise something that is no longer there—how to make present something that is no longer physically present.

With 'Night Coming Tenderly, Black', I thought about that poem by Langston Hughes, 'Dream Variations' (1926). The title for the project comes from the last couplet of that poem, 'Night coming tenderly / Black like me', and this notion of Blackness being a kind of tender embrace.

As I thought about the underground railroad, and African Americans moving through this blackness, and the tender embrace of blackness that would carry them to liberation, it began to give me the conceptual framework. The material framework for that work comes from Roy DeCarava. If you describe a narrative of Blackness, a Black subject, and a materially black photograph, well, that pretty much describes DeCarava's work.

SMI was a curatorial assistant for the Roy DeCarava retrospective in 1995. He signed my most treasured book.

I had known DeCarava for a very long time. He was very accessible to us younger, Black photographers in New York.

I never make work as an exercise in visual nostalgia. It's really meant to promote a conversation about how these sites and this history are related to the contemporary moment.

That sense of materiality—of blackness, of darkness, and how it has that tenderness in your series and his work is incredible. You feel like you're walking into a mystery that you ought to understand, or at least need to research until you do.

DBVery much so. So that work was very much materially inspired by Roy DeCarava. I don't know if you have seen the 'Night Coming Tenderly, Black' photographs, but they're very large because I wanted them to have a sense of physicality. And then a very particular kind of materiality—this wonderful tender blackness that Langston Hughes describes.

SMIt's almost a whispered blackness. In other words, there's something shimmery or effervescent, thinking about how oral histories are passed on. And you feel like you can hear a whisper when you stand in front of these pictures.

DBPhotographs are objects that are very particularly made but we tend to think of them largely as images. DeCarava reshaped my thinking around that from the very beginning; the photograph is not only what it's made of, but how the object was realised materially to shape the narrative of the subject.

With this work, I wanted to take on this notion that, within the landscape tradition, there have not been many works made around the notion of Blackness. Many conversations around Blackness and representation centre on the Black body; the Black figure. There is not a very long or rich tradition of Blackness being engaged and interrogated through traditional landscape.

I wanted to insert a Black narrative into the landscape tradition, beginning with 'Night Coming Tenderly, Black'. Some of the photographs have references, like Alfred Stieglitz's The Pond—Moonrise (1904). But Stieglitz wasn't talking about what I'm talking about.

SMNeither was Paul Strand.

DBStieglitz is someone whose work is very much a part of my history, work, and vocabulary. I'm very deeply based in the tradition of photography, all the way back to Louis Daguerre in the 19th century and up to the contemporary moment. It's something that matters a lot to me. I always consider the work that I'm doing to be in conversation with the history while adding to it.

SMI think you make that history matter through your work. They are what brings renewed interest and value in thinking about what that history is.

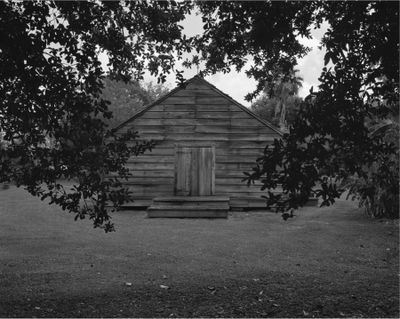

Your most recent project takes place even further in the south. Will you speak about 'In This Here Place' (2020), in terms of how you're thinking about landscape, architecture, and history that was maybe told in a very different way?

DBThe title of this project, 'In This Here Place', comes from Toni Morrison's Beloved (1987). Part of that reasoning is to acknowledge my cultural forebearers and the work that has influenced me, while making clear that the work I do is a part of a larger history of Black cultural production.

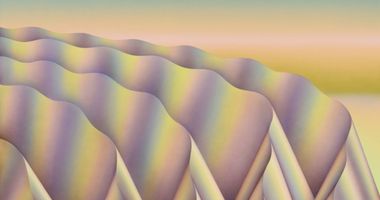

The photographs are made on and around the landscapes of five different plantations in Louisiana, along the west bank of the Mississippi River. I wanted to look at the places that are foundational to the long history of Africans, and then African Americans, in this country. These are the sites where that begins.

I wanted to go back, partly as an act of witnessing, but also to make work that would bring these sites and their history into our current conversations. Because it is certainly the history that began the set of complicated, messy, and often horrific relationships that continue into the present.

I never make work as an exercise in visual nostalgia. It's really meant to promote a conversation about how these sites and this history are related to the contemporary moment.

The plantation experience explains so much of our current history, and the tensions that still exist. If you understand this history, George Floyd is not really an aberration. When people say how could that happen? Well, here's how it could happen.

That's the way it was supposed to happen, from the ways this country was structured and what Africans and then African Americans were brought here for, and how Black bodies were abused. I tell people all the time that there are no mysteries in history. History explains everything.

So I spent two years on and around the plantations in Louisiana, making work there to engage, try to visualise, and in some ways, come to terms with that history.

SMHistory may explain things, but I think what your photographs do is they make us want to attend to that history.

Do we have any questions from the audience?

QCan you talk about your technique and your use of digital versus analogue? What do you think works best for you and why?

DBI think it was probably most meaningful in relation to 'Night Coming Tenderly, Black', which I initially tried to print as pigment prints, which are prints made with ink. But it simply wasn't possible.

Then, I thought about why DeCarava's prints look the way they do, because there's a richness, depth, and a range of tonality within them—of blacks within blacks, and that is something only a gelatin silver print can produce.

The silver halides are embedded in the paper, not sitting on the surface, as ink does. And these prints are further manipulated to give the appearance of being made at night-time or dusk, which they are not. But it's a material manipulation that silver prints allow for.

SMThat's not easy, even with silver gelatin paper.

DBSilver gelatin paper can do very particular things materially and that materiality was very important to those pictures. The rest is just my habits; I had been photographing with film for a long time—it works for me, so why change?

The other piece is the relationship of the tools you're using to the kind of object you want to make.

SMI'd love to hear you talk about scale, too.

DBTo make a large print with the quality of material description that I want my work to have, you need to start with a relatively large negative. Because the more you enlarge the negative, the more the print materially degrades.

So that's why, without getting too technical or going into brand names, I'm using a medium format camera and photographing with film. The camera is also on a tripod—it's important to say, because they're very precisely made.

SMIt's part of their dignity and presence.

DBYeah. Just a part of my process for making a very particular kind of photographic object.

QI was struck by what you said, Dawoud, about the conversations you had while making 'The Birmingham Project', and that history.

Did that influence the direction of the project? Did you have to consider people's sensitivities or maybe aversions to remembering that history, or their inabilities to approach it meaningfully, and not too painfully? What was your process like in negotiating?

DBIt was an interesting process. Part of it was familiar because I've been making portrait-based work for a very long time, and 'The Birmingham Project' consists of portraits.

My conversations were really important to the making of that work and several conversations were going on. I would go into schools to talk to young people about the work that I was doing, because I knew I wanted to make photographs of young people who were 11 and 14—the ages of the girls, the boys were 13 and 16.

One of the things that I quickly realised, speaking with young people, is that they are all very familiar with that history. So obviously, someone is doing the work of keeping it alive for them.

I had a conversation with one older woman, and she said, you know, through this project, you're making me think about things that I haven't thought about for a long time. She said that I was reminding her that her parents never spoke about the things that were going on at the time.

I think that's an interesting notion, because people might mistakenly believe that horrors that took place during the Civil Rights Movement could be dinner conversations, you know?

She told me that in Birmingham, the Black community was nicknamed 'Bombingham', because the Ku Klux Klan and other white racists would dynamite people's cars and homes to keep folks terrified, so the sound of dynamite exploding was common.

She said one night, an explosion went off right across the street. She asked her mother what it was, and her mother said not to worry, to minimise the fact that they were essentially living in a war zone, so that those kids could get up in the morning and walk out the front door with some level of confidence.

After several weeks of reaching out to older adults, many women had come forward to be subjects for the project. I was hanging out in the Black barber shop downtown, where I was hoping to find men who wanted to participate—including the barber in that shop, who I knew was the right age—and someone told me that this history was not something we necessarily want to think about.

Later, I met Carolyn McKinstry—now Reverend Carolyn Maull McKinstry—whom I had been wanting to meet, as one of the girls who had been in the girls' room with her friends before the explosion went off.

There were six girls who were together there. Four of them were killed, one of them—the one whose picture I saw with the gauze bandage—was seriously wounded. Carolyn McKinstry, who was the Sunday school secretary, had gone to hand in the Sunday report to the church secretary, as she realised it was getting close to service time. Just as she got on the stairs to go upstairs, the explosion went off.

I told her that not a single man had come forward to be a subject, and this project wasn't going to work unless men participated. She got on her cell phone right then and started calling all her male contemporaries.

She told them that she was standing there with me, how much she loved me, how we felt like old friends, and that they had to participate. And finally, because of her reassurance, and deep connection to that history, the men agreed to participate, including the barber.

All kinds of meaningful conversations were necessary for the project to work because I was coming in from elsewhere.