Firenze Lai

Firenze Lai. Courtesy the artist.

Firenze Lai. Courtesy the artist.

Firenze Lai says that she knows her studio of a few hundred square feet intimately; from the textures of its surfaces to the way the breeze blows into the room. The spaces depicted in her paintings are equally intimate.

When curators seem to be at a loss for words to discuss troubled times, fear of containment, and the feeling of being completely enmeshed in a space, they turn to Lai's paintings, which have been shown as part of Para Site's A Journal of the Plague Year. Fear, ghosts, rebels. SARS, Leslie and the Hong Kong story (17 May–20 July 2013), and A Hundred Years of Shame—Songs of Resistance and Scenarios for Chinese Nations (6 March–17 May 2015).

Further, Lai has shown work in international solo and group presentations, including Turbulence at Mirrored Gardens in Guangzhou (29 October–28 November 2015), the 10th Shanghai Biennale, Social Factory (23 November 2014–31 March 2015), the 2015 New Museum Triennial, Surround Audience (25 February–24 May 2015), and in Venice for the 57th Venice Biennale (13 May–26 November 2017). More recently, a selection of nine of Lai's paintings appear in Tai Kwun Contemporary's Contagious Cities: Far Away, Too Close (26 January–21 April 2019).

While enrolled at the Hong Kong Art School, where she graduated in 2006, Lai would draw through the night. After graduating, she worked as a freelance book designer, and since 2011 Lai has been painting and making drawings in a professional context. Her works often feature anonymous figures entangled with their surroundings, such as the curvature of the Hong Kong subway walls or even the space beneath a desk.

The figures are rendered in seemingly localised specificities, yet they could be anyone, anywhere. It is these conditions that allow for a reading of containment that Lai is focused on articulating. The psychological landscapes are dark, moving past the emoting surface of human faces and into the recesses of raw feeling. One painter that Lai admires is Francis Bacon, and she says that throughout her practice she has always strived for one thing—an intuitive primacy in capturing the essence of the thing itself.

In this conversation, Lai talks about the universal essence of her anonymous figures and the influence of Occupy Central on her practice.

HCCan you tell me about the anonymous figures in your work?

FLI make figurative work, not portraits. This kind of figurative work is universal. I don't stress the gender of the figure—sometimes it's there, but it's not very important. I want to capture that figure's empathy. I don't want to remind the viewer that there is a painter here, and I try not to emphasise the hierarchy between the artist and the figure in the painting, or the painting and the viewer. If a work is a reflection, the viewer can relate it to themselves and not be so aware that the artist has put something there to project outward. I take out markers of individual identity and leave the quality of the material.

HCHow would you describe this quality?

FLI can't answer exactly what that quality is, but I can say that through all of my works I am looking to express the same thing. As I told you, it's about a sort of empathy. Right now, you and I are sitting here—we have different backgrounds yet somehow something is shared between us. For example, if I tell you I am very nervous and I cross my legs, I'll be seen as nervous. You would get that. If I'm scared, I'll get goosebumps and I'll shiver, and you would understand that too. These expressions are individual yet collective. I emphasise that in my work. It's like there are many doors, and many different people, and the door a person chooses to open is theirs. Everyone can have a key to enter that room.

HCWhere do the titles come from?

FLI really like making titles. Bus Journey (2013) and Central Station (2013) have to do with life experiences. There's one oil on canvas work called The Hollow Passage (2017) based on the curved wall of the platform of Causeway Bay's underground station. If there are many people, you have to stand against the wall and you feel its curve, which inhibits you from standing straight. I think it's on purpose. It affects your movement in the space.

These life experiences make up one's entire world. If you were to come to Hong Kong from America, where you can see the sky in 180 degrees, the high-rise buildings would make you feel uncomfortable. Many people ask if my work is about the scarcity of space in Hong Kong. I can tell you my work is not about the scarcity of space, because I grew up here. Of course I have my moments of discomfort, but these details in everyday life, such as the height of this table, relate to day-to-day experience.

I was once in Admiralty underground station and I noticed that the straight line that indicates the queue on the platform had been changed, without notice, to a slanted one. The next morning, unawares, everyone followed the slant to line up. The straight line had been there for decades, yet once they changed it, no one asked any questions. It's so easy to manipulate a group of people through these details. You have to be aware or you become unaware. This is important.

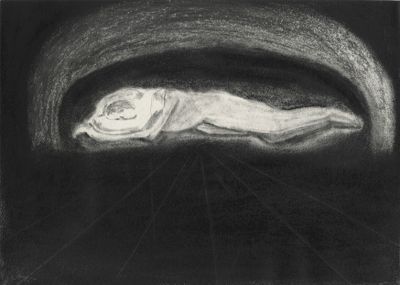

Some titles are literal. This one is called MRI (2015). A few years ago, I had some bodily complications. When you do an MRI scan, you become a piece of meat on a platform being pushed inside a chamber with low humming noises. You know that something will perforate your body and that becomes a reading. You don't know what this reading is but that it has determined what your condition is. When you're inside, you become humble, vulnerable. You don't have to get an MRI to feel this. The title is a hint.

HCIt looks a cave and also a womb.

FLDo you remember the first time you went camping? That feeling of being safe inside a tent while outside, beyond the thin cloth, the wind and the natural landscape surround you. My spatial awareness is very narrow. It extends to about 200 feet. But inside that space, feeling is very strong. For example, when I speak to you now, the surface of this yellow table gives a strong feeling. It's about the condition of things, the state of them. In my work, the space I show is about 100 to 200 square feet.

HCWhat are you working on now?

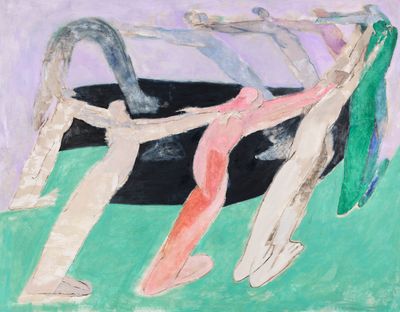

FLMost of the works I have mentioned are inspired by a specific situation in real life, such as riding the subway, going to the cinema, or travelling by bus. But I have another kind of work, which in a way is less realistic. They are more focused on some abstract sentiment, such as Tilted Circle (2018), which is how I feel about the recent atmosphere of our society.

Some people are trying their best to hold on a bit longer, and they have to trust and rely on others. It is somehow okay at this moment, but no one can guarantee what will happen next. It's important for me because I always wanted to make this painting. I had tried many times, and this is the first time I think I managed to capture the impossible balance that I wanted to show. This is one I made after Occupy. Were you in Hong Kong at that time?

HCNo I wasn't, I was in Montreal. I was working for a student newspaper at the time and I covered a solidarity protest held by Hong Kong students there. Many of them were exchange students. At the end they sang the song 'Hai Kuo Tian Kong' by the band Beyond.

FLI always feel that I am broken off from society. To a certain degree, my relationship with it is separated. During Occupy, I was mad at myself. All along I hadn't cared about these things—politics—because I didn't feel as if it had anything to do with me. Many forms of awareness began at that moment. Every night at Occupy, I would go on Wikipedia to look up what the political parties have done in the last ten years. I studied who said what and when, and what promises had been made to the Hong Kong people. The events of Occupy have had an effect on my work.

HCHow would you characterise this influence?

FLAfter Occupy Central, I began to think with an added layer. Who decides that this wall is curved, making people stand so uncomfortably? Why can I only cross the harbour at this subway station, and not another? Many things become very political when you start questioning them like this. You could tell yourself that these are just life experiences, but I can't trick myself.

Before Occupy, I was already suspicious of my surroundings and whether they were manipulating me. Now I feel this even more strongly. Everything has a system behind it. This table, its history and development, through to when I picked it to sit here with you and present its history, the whole thing is very complicated. To start thinking like this has made me very careful about what I put on the surface of my painting.

HCAre some of the figures in your paintings inspired by your experience of Occupy Central? You said there are people who have big ideals, who see the bigger picture, and many who are just looking at what's directly in front of them. Are the people in your paintings the ones with big ideals or the ones who only see what's in front of them?

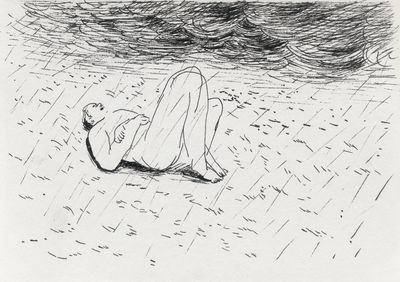

FLAfter Occupy Central I made a drawing into a postcard, called Cloud Observer (2015). On Facebook I wrote, 'If you ever laid down,' because we never lay down in the middle of the road, 'send me proof in a photo and I'll mail you a postcard.' A lot of people sent me photos. In this intense milieu, where people were fighting, a person was lying down looking at the sky. They felt they had never tried it before.

In the first few days after Occupy began, there were a lot of comments online saying, 'It turns out the road is a very comfortable place to lie down', and 'It turns out the railings on the corners are comfortable to lean against.' When you are chasing an ideal, you have many frustrating moments. But in many small moments, you can experience something very new. —[O]