Gary Simmons: History as Residue

Gary Simmons. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures.

Gary Simmons. Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures.

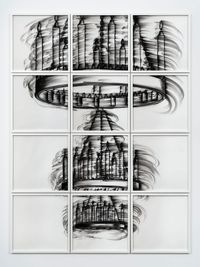

Gary Simmons' eleventh exhibition at Metro Pictures, Screaming into the Ether, was initially scheduled to open at the gallery's New York location on 26 March, but was moved online due to the coronavirus emergency. In the gallery's online Viewing Room, Simmons' latest body of work remains visible to the public, and strikes piercing new chords in the artist's ongoing investigation of the insidious nature of racial stereotypes in popular American culture.

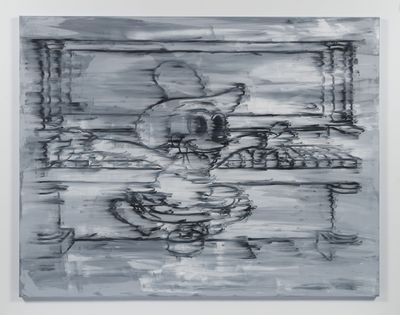

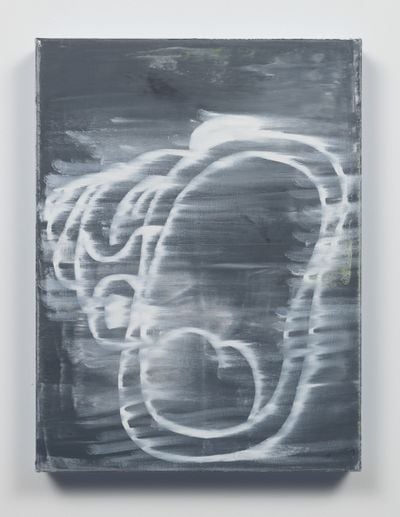

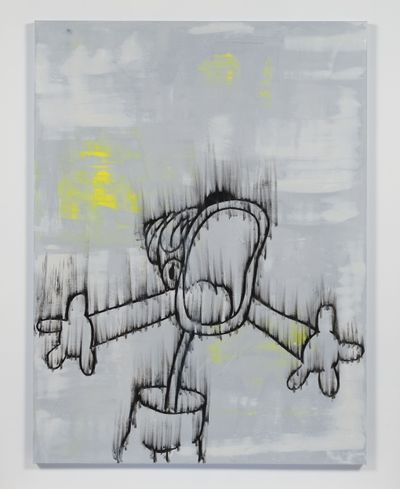

The figures that populate Simmons' latest canvases are based on the 20th-century cartoon characters of Bosko, Honey (Bosko's girlfriend), and Bosko's 'Little Sister'. Presented for the first time in an animated short from 1930, Bosko was the first character of what would become the Looney Tunes franchise. His visual features, movements, clothing, and speech patterns match the era's prevalent stereotypical caricatures of African Americans. The materiality of the source animations is echoed in Simmons' canvases and their black, white, and grey colour palette, as well as in his blurring of the figures' forms. While this technique offers a sense of motion akin to the original cartoons, it also emphasises a tension between stasis, slippage, and progress in the characters and what they represent.

After completing a BFA at the School of Visual Arts, New York, in 1988, and an MFA at California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), Valencia, in 1990, Simmons rose to fame with works in which he partially erased sections of images he had painted or drawn. The approach was initially honed in chalk drawings on slate-covered paper, but he has since also applied the effect to paintings on canvas and large-scale murals that use text, figurative imagery, or both.

Simmons sees the chalkboard as a surface for 'teaching, learning, and unlearning'—a perfect match for his central fixation with how cultural memory is constantly constructed and reconstructed. The artist's early chalkboard drawings investigated these questions through the appropriation and re-examination of vintage cartoon characters based on racial stereotypes, which he continues in Screaming into the Ether. Canvases become palimpsests in which history is written, scraped back, and rewritten, never fully disappearing. This sense of temporal static is perhaps most palpable in Piano Man (2020), in which Bosko sits playing a piano, his head turned towards the audience with a smile that takes up most of his face. The lines of the image pulsate left and right in a series of sharp horizontal movements that displace the details of the image into a dizzying form of itself.

The 20 paintings that comprise Screaming into the Ether, alongside the artist's overarching practice, make clear that such figures as Bosko cannot be simply reabsorbed into the pen, the slate wiped clean. Instead, they linger as ghosts of prejudicial views that stain cultural memory and the psyches of the peoples they depict. The exhibition's titular painting, in which Bosko seems locked in a never-ending scream, is based on a still from The Talk-Ink Kid (1929)—Bosko's pilot animation. In the scene captured in the still, Bosko sings an off-key note until his animator (a live-action figure and the only other character in the short) cuts him off by stabbing him with a fountain pen, pinning him down and then absorbing the lines of his form into the pen.

In this conversation, Simmons spoke with Ocula Magazine about his approach to his latest exhibition and some of the key moments over the 30-plus years of his practice.

CCA number of your painting and drawing series have taken motion pictures—their titles, actors, and images—as their source material. Could you talk about your approach to this process?

GSWhen I begin working, I usually study an idea through looking at many films. I do a lot of research with the internet or picture libraries—everything I can get my hands on—but film is often the first place that I go. Films—specifically, historical films—recall memories and shape stories and histories in an interesting way. When dealing with a political issue, I might even reach back to the silent film era for inspiration.

When you attempt to erase something, there's always a trace left behind.

CCOf the numerous stereotypical animated characters of the 20th century, what drew you to Bosko and his co-stars for the paintings presented at Metro Pictures? Some critics have described Bosko as less extreme in its stereotyping than other contemporaneous characters; did that play a part in the decision?

GSBosko is one of many characters that I look at as far as race films are concerned. Many race films from the early part of the century were cartoons that were intended to bridge double features. In between a double bill of two feature-length films, they would have these politically based race cartoons that use bigotry and racism as sources of imagery, and then they were banned. I was looking back not just at Bosko, but at a lot of different imagery of that type from that cartoon era.

Bosko became an interesting character for me in his relationship to Disney characters. A lot of cartoonists would take pictures reminiscent of something out of popular culture and change the image slightly to make it more palatable. The visual shifts between two characters could be very subtle. The defining icon for a female character such as Honey might be her bow. I used broader figuration in my work early on and then I started to pull out certain markers that represented race or gender—the bulging eyes, the bow, the lips—and they would take on their own language in the work.

CCMusic was a big component of early animations such as Bosko's. Translating these animations to paintings isn't just a translation from moving image to still, but from audio-visual to visual. How does this translation operate for you?

GSFilm and music work hand-in-hand in their relationship to memory. Having spent a lot of time around musicians, deejaying and other things, you realise that people anchor personal and historical moments either by having seen a film or listened to a song. I've always been drawn to those connections as a visual source.

I see myself almost as a visual deejay, because I'll take images, song titles, or lyrics, and fragment them to create something new, in the same way a deejay takes a sample or a hook from one song and couples it with a completely different other thing to create a new beat. I try to do the same visually—I'll take a fragment from one cartoon and mix it with another. I'll pick and choose what I'll leave out, forcing the viewer into completing the image in their own memory. That goes hand-in-hand with the notion of erasure. When you attempt to erase something, there's always a trace left behind. The viewer, through their experience and memories, then completes the image on their own.

CCIn the short from which the Metro Pictures exhibition's titular painting is extracted, Bosko is singing an off-key note, rather than screaming as the title suggests. Could you talk a little bit about this shift?

GSThat again underscores the fragmentation. You can take something that in its source might have one meaning, like singing or talking, and by removing bits and pieces it can become something else. When you confront an image directly, you begin to question the original source and even the importance of the source, because it takes on a completely new meaning.

That approach comes out of the Pictures Generation, which was slightly before me. That attention to contextualising or recontextualising something asks you to look at the image and think about where it comes from, what's left out, and what's in between. That's where I think the work's strength sits. It's not just taking the cartoon and leaving it in its original source.

At the point of erasure, nothing is planned out.

CCThe work's title, Screaming into the Ether, implies a certain hopelessness—that the cries of protest that Bosko embodies will fall on deaf ears. Do you believe this is the case?

GSThat painting is a beautiful image for this moment—it has a lot of what you're talking about. We're in a period of protest, where there's a feeling of helplessness where we keep repeating ourselves, but nobody's hearing or things keep happening anyway. I saw on the television that in L.A., there are Covid-19 deniers out protesting with no masks on, probably passing the disease on to each other; then when they turn around and get sick they'll have to go to the people that they're protesting against.

I'm not quite sure how far things have to go before people start to hear the folks who are screaming into the ether. It's like standing on a cliff and yelling, 'Hey, this is coming', and nobody's listening. But there is also a catharsis to screaming like the painting's character appears to be, out of rage or whatever. We have all had that feeling, where something is more than you can bear.

Occasionally, I'll use a title that's connected to the image because it helps me catalogue the work. The title might be 'Blue Star' because the image is literally a blue star, but generally my titles are very carefully selected. I use a lot of songs from groups that I'm drawn to. Step In The Arena (The Essentialist Trap) (1994) and a number of other titles come from Gang Starr, which is one of my favourite hip hop groups. For me, Gang Starr's DJ Premier is one of the best deejays ever because he has this vast music catalogue in his brain. He takes very different musical references and puts them together to get Gang Starr music.

CCOver your career, you have created multimedia installations and vividly multi-chromatic collages in addition to your monochromatic paintings and drawings. How do you think your other works have affected these black-and-white paintings? And how do you think such paintings have in turn affected your other works?

GSCalArts always stressed that every mark and object in your work has to have a reason to be there. Like notes in a song or words in a paragraph, every part is selected very carefully. There was no randomness to the early colour palette. It was very much about stripping down the image, so if I introduced colour, there had to be a reason. The first time that I really used colour, it was quite jarring because I was so used to making it all about the imagery and how that was being altered.

You can take something that in its source might have one meaning, like singing or talking, and by removing bits and pieces it can become something else.

1964 (2006) was probably the first time I used colour directly. It was a series of wall drawings that used the RGB format: the structure of film imagery. Those colours had a very specific reason to be there and it made me feel more comfortable using colour. If you're too rigid in your conceptual approach, you can paint yourself into a corner over time; the colour opened me back up. A lot of my imagery opened up at this time. Architecture as a source for criticism became a lot more frequent, targeted, and important. I became not only grounded in cartoons and text, but also modernism and that kind of thing. It created more avenues for the viewer to enter the work, because the base was still the notion of erasure.

At first, the black-and-white palette was relevant because it was connected to the chalkboard as a pedagogical place for teaching, learning, and unlearning, and in turn gave me reference to this idea of erasure. But once that became part of my visual language, I could incorporate colour and other things in tandem with the erasure.

CCYour first use of the erasure technique is often talked about as a pivotal moment in your work. Could you share one or two other exhibitions or events that you have experienced as cornerstones in the development of your practice?

GSAs you move through your career, you hit some shows or installations that take you in a completely different direction. I did some sound pieces early on, from perhaps my second installation at Metro Pictures, Sound Garden (Sound Drawing from the Garden of Faded Markings) (8 April–13 May 1995). I used the sound of dance and basketball, and the piece erased itself over time—as the tape repeated, parts were left out so that it became this very staggered thing. That was more like a translation of the drawings and paintings.

My stacked speaker piece, Recapturing Memories of the Black Ark (2014) really opened me up to different places. I was initially primarily an object-maker. I wanted to create something that used that interest and also had a personal component to it: Jamaican sound systems. It was a living sculpture that invited musicians to perform on a provided stage on their own terms. After their performance, they left the speakers in whatever configuration they used. That has a different sort of ghost tracing than the drawings, but they're related.

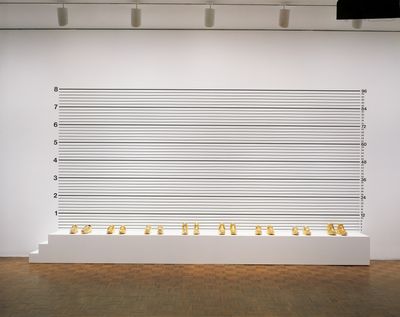

One of my earliest pieces was 6X (1990): these child-size Ku Klux Klan robes on a rack. That was pivotal and remains a cornerstone for a lot of the work. It's very shocking in some ways—taking something so politically and emotionally charged, and turning up the volume even more by presenting children's suits. My work took off in a different direction once I made it. It was very early on and had nothing to do with drawings or paintings. If you look from then onward, most objects like that have a direct political charge. The sneakers, as in Lineup (1993), came afterwards, and the implication of bodies in a space gained a life of its own.

CCYou have been incorporating cartoon figures such as Bosko into your work for about three decades. The world has changed a lot over that time. How have national and international events, and the passage of time more generally, altered your approach and how the work is received by the viewer?

GSWhen you put an image down, you hope that it will have a longevity to it and feel fresh and relevant many years later. People remain drawn to what I was dealing with 30 years ago because the issues are still around, and that's sort of sad. Who would have thought that, world-wide, this resurgence of the right would occur? It's like the more things change, the more things don't. A number of us were on to something, but it's bittersweet because we would have hoped that by now, we wouldn't be looking at the political figures that we are.

These issues are going to be with us long after I'm gone. I see the younger kids look at some of the stuff that I look at and they're jarred by it. They say, 'Wow, can you use that imagery?' And I say absolutely. It's a language like anything else. I don't think that it should be censored; you can't shy away from it. You have to put it out there in people's faces.

CCHave you found that being a father has changed your practice?

GSYou start to think in terms of legacy, in terms of the types of subject matter that you're dealing with. You ask yourself, can my kid look at this and take from it what she will take? She will be confronted with a lot of things that I've dealt with, so I think being a father also creates an urgency.

When you're younger, your goals and the opportunities in front of you are very different. You want to make big statements and marks because you're not quite sure you will have the chance to make those gestures again. As you move forward, you become a little more comfortable with the notion that this work is amassing a history and an importance. The hope is that the subject matter and voice then stay critical. I have a kid and if I were to leave, I don't want to have regrets.

My approach to the studio also got more serious once I had my daughter. A young person always thinks that there's endless time, that you can go out and party with friends and the studio is always there. Once you have to parse out time for studio and time to raise your daughter, that studio time becomes very precious and it has to be very serious.

CCA few of the Metro Pictures paintings break from the black, white, and grey colour palette by using sparks of yellow. Could you talk a little bit about the decision to incorporate these breaks?

GSI think that's me allowing myself to be playful. I was considering the antiquing of chalkboards. Over time, the surface colours often change, and I'm interested in that. Although they aren't chalkboard paintings, these pictures are similar, and I was drawn to the highlighted areas that can also create depth in the painting.

At first, the work was an image on a chalkboard and that was it. Over time, certain painting issues started to come into play, allowing me to step into the painting arena. Creating depth, ghosting, and colours that appear or disappear, pushing an image back and bringing it forward, or layering something over the top started to become aesthetic choices. Those flashes of colour happen as part of that.

There are many layers to those paintings. Some are probably 20 layers deep. The surface is distressed; I'll paint on one colour and then scrape it all the way down or leave certain areas to build. There's a lot of push and pull. Those colours sometimes start to show up over the course of layering and scraping. The colours came through letting myself learn about surface, paint, and application.

CCYou have moved between New York and Los Angeles a number of times. Does each location have a different affect on your approach?

GSNew York's my home. I'll always be a New Yorker, even though I choose to live in Los Angeles. This is probably the third time I've lived here—I went to graduate school here, I've flown back and forth, and I have a tonne of friends here. I took a job in the early 2000s at USC [University of Southern California], only to have to turn right back around and return to New York after 9/11, but my wife and I always said that if we had a kid we'd love her to spend half of her childhood in New York and half in Los Angeles, so that she could make an informed decision as to what coast she wants to live on. I think it worked out that way. She loves New York and it's still her home, but she also loves L.A. and the freedom that she has to move around.

Conversely, because there's such a car culture, kids are dependent on parents for travel. That's totally the opposite to New York; my daughter's 13, and by the time I was 13 I was taking the subway all over the city.

There are gaps in the erasure paintings like there are gaps in your memory—pauses where you have to piece things back together.

From the moment you wake up to the moment you put your head on the pillow, there's always something to confront in New York. But I'm drawn to L.A., largely for its physicality. Out here, space is afforded to you that you can't have in New York. L.A. is a horizontal city; New York, Chicago, and San Francisco are all very vertical cities. L.A. has the sprawl. Even when you're in your car, there's the feeling of space and depth—you have a spatial relationship to the landscape that's very different. I think that has found its way into the work, with an interest in creating space within the frame becoming central.

You can get more actual physical studio space for what you can afford out here. In New York, everything is a battle, and you have to ask yourself, how will I produce a big show in this tiny studio? Those issues are erased—no pun intended—in Los Angeles. I would get my energy from walking around New York from the time I was very little, but as you get older you want the opportunity to take a step back—not too many steps, but just one—to analyse things. You need the physical space to actually see what it is you're looking at, and L.A. creates that for me.

CCThe word 'erasure' often refers to the whitewashing of history and culture, but in these paintings, whitewashing works to wipe away stereotyping imagery. Could you talk more about this word in relation to your approach and its usage more widely?

GSThere's the literal notion of erasure, and then there's the psychological dimension and the attention to the way histories are erased and recreated. There are gaps in the erasure paintings like there are gaps in your memory—pauses where you have to piece things back together. Once I drag the image, certain hard lines are completely blurred or obliterated; the viewer then has to fill in those remaining fragments.

That filling-in mirrors how we think about personal history. Over time we start to forget, and then we reinvent. I've always been drawn to the idea that somebody can tell you a story and somehow that story becomes your own—you might have been told about something that happened to someone else in such detail and so often that you'll retell the story and almost forget that you weren't there. That slippage is very important to me. Gaps, and the way we fill them, are where representation and abstraction meet. And that's really what the erasure series represents.

CCYou have talked previously about how you enjoy the fact that your wall drawings become part of the space's architecture once they are painted over. This is your eleventh solo exhibition with Metro Pictures; though not all these exhibitions have occurred on the same site, it does feel like you are building layers of history within the gallery.

GSWhenever I do wall drawings, they're very big. Originally, they came from the scale of movie screens, so there's a sense of monumentality and movement implied. As you look closely, you can see my fingertips, blood, and every mark that's left. People will look at them and go, 'Oh my god, it's so beautiful and it took you so long, what happens at the end of the show?' I tell them it gets painted out, and they say, 'No, what do you mean it gets painted out? Aren't you sad about that?' But it takes on a whole new place in your memory that way.

I've always been drawn to the idea that somebody can tell you a story and somehow that story becomes your own

You could take a photograph, but a lot of the work is very experiential. Generally, reproduction doesn't do justice to seeing any artwork in person. One reason I love making visual art is that it provides one of the last opportunities to go and see the work itself. A [Gerhard] Richter painting in person is very different to a reproduction. I'm not comparing myself to Richter, but you do have to experience the work—especially the wall drawings—to understand its power. It then lingers in your memory as this personal experience. Once it's painted out, it's embedded underneath all that paint and all those other shows. Usually, if you look very closely you can see that razor line where the wall drawing began and ended. I like that.

The internet is different. It's a little weird having a show up with no bodies actually moving through the space. It might be the new way of seeing work now. I can't speak to how things will be from here forward, but it is interesting to have shown with the same gallery for so many years in so many spaces. The work does have this lingering history, and I hope that that happens online as well.

CCSo the paintings are installed in the closed gallery right now, by themselves?

GSYeah, we installed them over FaceTime. The gallery assistants would place things and I would say, 'Let's try this one there', and then they would take photographs or FaceTime the wall. It was very strange, seeing the space on a small phone.

CCThe idea that while I'm looking at the online Viewing Room, these paintings are installed in the closed gallery space alone is so eerie. I can almost imagine a live feed in which we watch these paintings, still on the wall, in an otherwise empty space.

GSA ghost show.

CCYour repetition of the 'Little Sister' character's pose in Dance Little Sister (2020) and North Star (2020) seems to emphasise such images' infinite and sinister reproducibility, akin to the broomsticks in Fantasia. Could you talk a bit about your decision to use that same pose in both images?

GSI'll often do multiple paintings of images in different variations. The backgrounds change and even the erasure changes, but the source image will be similar. I've always said I can take one image and do it ten different times, and you'll have ten different paintings, because of the erasure's immediacy. Dance Little Sister is milkier; she's in a greater state of disappearance in some ways. I was imagining a scrim or a curtain falling down in front of her, or how an analogue photograph shimmers to the top as it is developed. That approach is a little different than in North Star.

CCYou talk a lot about the physical act of the erasure. I read that you often have assistants aid you in painting the image, but that final movement is always all you.

GSIf I were to ever do an exhibition over a phone, I could probably do it with Colt Hausman. He worked with me for years—he knows my gestures and he knows how the surfaces are put together. We work like hand and glove. We don't work together anymore because he's in New York and I'm in California, but we're a lot alike and he's maybe 20 years younger than me, so he's almost a little brother. Still to this day, if I'm exhibiting somewhere and I can't be there, say in Seoul, I'll call Colt and ask him to fly to Korea to prepare the show so I can get there two days before the opening and do the erasure, and he'll be on it. He's incredible like that, and a great artist himself. It's amazing to work with somebody like that, but the end result—the actual erasure—always has to be me.

The erasure is a type of action painting and much of it depends on my emotions that day: a lot or a little of the image might be erased; the direction might change or shift. At the point of erasure, nothing is planned out. I can plan most of the painting, but I've become more willing to allow unpredictable occurrences over the course of layering, and the erasure is the same way. There's no telling what it will look like at the end of the day, so that's why it has to be me.—[O]