Hiwa K

Hiwa K. Photo: Sarhang Hars.

Hiwa K. Photo: Sarhang Hars.

Artist and musician Hiwa K was born in Sulaymaniyah, the cultural hub of Iraqi Kurdistan known as home to many Kurdish poets and writers. At the age of 25, before the 2003 invasion of Iraq, he left the country and travelled via Iran, Turkey, Greece and other countries to Germany, where he began studies in music and guitar with Flamenco master Paco Peña. The dislocation from and transformation of the place he used to call home are key aspects in the life and work of Hiwa K, who considers himself largely an auto-didact in European literature and philosophy. His manifold approaches toward vernacular forms of knowledge, modes of encounter and political struggle are profoundly inspired by personal memories and oral histories. The collective and participatory dimension of music plays an important role throughout his artistic inquiry into notions of belonging and estrangement.

During a residency at Serpentine Gallery's Edgware Road Project in 2010, K founded the 'Chicago Boys', a 1970s revival band and neoliberalism study group. The ongoing, collective and transnational project attempts to practice an alternative model for reflecting on the globalisation process and its impact on our daily culture through the lens of cultural dynamics, particularly those in the popular music genre. For about two months, band members without musical training and from different professional and cultural backgrounds collectively learn how to perform, while studying questions of free market economy in weekly group sessions. The project has been hosted by numerous international institutions since.

Among many solo and group shows, K has participated in the exhibitions of Manifesta 7 in Bolzano (2008), at the Wyspa Institute of Art in Gdańsk in conjunction with Alternativa (2010–2012), and La Triennale Paris (2012). In 2015, he was included in the 56th Venice Biennale exhibition curated by Okwui Enwezor, where he showed The Bell Project (2007–2015), which included a dual screen video capturing the artist's work with Nazhard, who operates a foundry in Iraq, and the casting of a large bell in a 700-year-old foundry near Milan. While still working on his ambitious production for Venice, K was invited to participate in documenta 14. In April 2016, his first ever solo exhibition in Germany marked the launch of his collaboration with Berlin-based gallery KOW, and only two months later, at the end of June, he was announced simultaneously as the winner of both the City of Kassel's biennial Arnold-Bode-Preis and the Schering Stiftung Art Award. In conjunction with the latter, K produced The Existentialist Scene in Kurdistan (Raw Materiality 01) (2017), a video work that was included in a sizeable solo exhibition, Don't Shrink Me to the Size of a Bullet (2 June–13 August 2017), at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art (KW) in Berlin. That exhibition marks the most comprehensive retrospective of K's work to date, spanning ten years of artistic practice.

In the months that followed the award, K worked on the production of four major works for documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel, three of them new commissions, and on his KW exhibition. All three shows opened within eight weeks of each other, between April and June 2017, with the KW show accompanied by the artist's first monograph, edited by Anthony Downey and published by Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König.

For this conversation, Jens Maier-Rothe spoke with Hiwa K about the last two years, working with documenta artistic director Adam Szymczyk, Darwinian blindness, and how good jokes and anecdotes can help us deal with the neoliberalism in everyday life.

JM

First of all, congratulations on all the projects you have accomplished lately. Juggling three major exhibitions in less than twelve months must have been quite a commitment. How did you manage to strike a balance between all of that?

HKActually, I spend most of my time with music. I practise guitar five, six hours every day; art is something I do on the side [laughs]. Due to the massive amount of work, I had to reduce my engagement with music dramatically during the last year. That was hard because I need music on a daily basis. The invitation to participate in documenta came in spring 2015; I had almost two years to prepare for it. Back then I was still working on my project for the 56th Venice Biennale. As soon as that was done, I travelled immediately to Greece to start producing for documenta. There was almost no gap in between. But working with the documenta team was great, they were really supportive on all levels. We produced four works together, two videos and two sculptures in public space.

Public art projects always involve a huge amount of communication and organisation. The first one I thought about was One Room Apartment (2017) in Athens. I'm quite familiar with the production process, I've done it several times before and it took us only a few days to produce it on location in Greece. Production on the other sculpture in Kassel, When We Were Exhaling Images (2017), also went very smoothly. One major challenge for me personally was to write decent scripts for the two new video works, Pre-Image (Blind as the Mother Tongue) (2017) in Athens, and View from Above (2017) in Kassel. I was very lucky that artist and friend Lawrence Abu Hamdan helped me with that. He's a native speaker and has done lots of script writing before. All in all, the time was quite stressful but I tried to just tune that out and get as much work done as possible. At some point, I just collapsed and my body said: stop! I immediately flew back to Berlin, although I was in Iraq and in the middle of working on a new project for the upcoming exhibition at KW in Berlin.

Thankfully, most works for the KW show were already done and the KW team knew that my presence in Berlin would be limited if the opening would coincide with documenta. We just faced some issues with the bell for The Bell Project (2007–2015): it would not fit inside the elevator at KW and would have been too heavy for the building. The sand installation, What the Barbarians did not do, did the Barberini (2012/2017), already weighs several tons and the bell would have added another 700 kilograms. But in the end, I was okay with the bell being absent. The exhibition space is not so big and I didn't want to squeeze too much in there anyway.

JMFor the first time in its history, documenta is not only taking place in Kassel. What did it mean for you to present work in two different cities and very distinct geopolitical contexts at the same time?

HKI liked the idea of dividing the event between two cities and also the title Learning from Athens, because in the end a lot of my work is about the circulation of culture, how cultures have been influencing each other for centuries and have become embedded within each other, both on a macro and on a micro level. When I stopped making art for six years and learned Flamenco guitar, it had a huge impact on both my music and my art practice, so much for the micro level. On a larger scale, we can look at the Islamic Golden Age, for instance. Most writings from Antiquity were translated into Arabic during that period. It's fascinating how much of the knowledge we have today originates from ancient Greek culture. In the video exhibited at the Athens Conservatoire, Pre-Image (Blind as the Mother Tongue) (2017), I say that I have been in this place already centuries ago. Rather than addressing exclusively the present geopolitical contexts—the economic crisis, the tensions between Germany and Greece, the vulnerability of the people, the violence of the financial markets—I wanted to dig into other, more historical layers but still connect them to a personal story.

A lot of my work is a mix between personal experiences and stories about a person who goes by the name K. The video work I present in Kassel, View from Above (2017), tells the story of how he memorises the detailed map of a city he claims to have fled in order to convince immigration officers in another country to grant him political asylum. His 'view from above' matches with that of the state official whose knowledge of the city is entirely based on a map, as he has never been to the city and seen it from the ground. I had written this text a long time ago and decided to make a film out of it based on the city map of Kassel. I worked directly with the artistic director of documenta, Adam Szymczyk, and we were constantly in conversation about my different works in the making. He was very helpful and never put me under pressure with regards to the direction I was taking. When it seemed that the city museum of Kassel would be one of the exhibition venues, filming the replica model of the city's destruction during World War II was of course close at hand. In the end, the museum decided to buy the work, which is really great because it adds a different and important perspective to their historical collection, one that is not only a piece of historical evidence but comes from another, external place and tells a more complex story.

JM

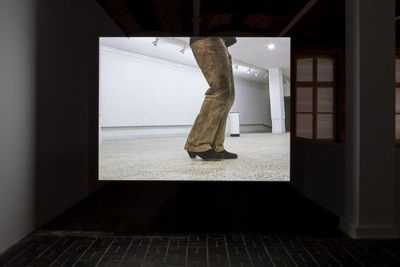

The video work Pre-Image (Blind as the Mother Tongue) adopts a performative gesture from an earlier video work, Pre-Image (Porto) (2014). In both videos you walk around balancing a long pole with car mirrors attached to it on your forehead. What made you revisit the same concept again?

HKMany of my projects are not so much artworks per se; they function more like tools or instruments that I can play with in different places and conceptualise differently each time, like a carpenter who brings his tools along. The device I'm using in Pre-Image (Blind as the Mother Tongue) appears not only in Pre-Image (Porto): I worked with it four or five times already, in Weimar, Gdańsk, Plovdiv and in Vienna. I continue using it and I will create an archive of all the different chapters one day. Sometimes people get confused, also collectors. They think that I have lost control over my works and do the same thing over and over again in different versions. But it's not like that. The pole with the mirrors is a device that serves different ideas. It's both an impediment and navigation tool at the same time, and influences me in various ways depending on the time and place in which it is activated.

The video I made for the exhibition in Athens is the most personal of all so far. I'm moving through territories that are very emotional and difficult for me. I felt unsafe in them due to my own biographical connections to these locations. I'm basically revisiting some of the places along the border between Greece and Turkey that K crossed on his trip from Iraq to Europe many years ago. I couldn't balance the pole so well because I was simply not feeling well; my memory of these places shattered my inner sense of orientation. In Athens, Ancona and Rome, all places in which I feel safe, I was relieved from this inner tension. You can see in the video how my movements change, I'm almost dancing... [laughs]. At some point in the video, I pass through Patras and you see a pile of drain pipes in the background. That moment is a direct link to my sculpture in Kassel, which is based on the story that K lived inside one of these pipes for several weeks while trying to access Europe.

JM

Your solo show at KW in Berlin spans ten years of artistic production. I noticed that while in your earlier practice you often aimed for finite works, many of your recent projects are open-ended and adjustable to context. The videos Moon Calendar, Iraq (2007) or Star Cross (2009) haven't changed much in ten years. The Bell Project (2007–2015) comes in different versions and also shares its roots with What the Barbarians did not do, did the Barberini (2012/2017). Is it a conscious decision to make more versatile and multivalent projects?

HKIt depends on the work and its story. As I said, some are more like tools for me and it's important for me that they are open and happen in different places. Performance and event-based works like Cooking with Mama (2005–ongoing) or With Jim White: Once Upon a Time in the West (2010–ongoing) are meant to be repeated. Although many people told me that cooking with my mother should have stayed this one-time symbolic event, they don't see that doing it in an art academy with students is obviously very different from doing it with Occupy Berlin members, for example.

Another aspect is to make several editions of one work. I'm usually happy if I manage to produce one work per year, but the last year was different, and I will never do this again ... [laughs]. I don't know how some artists manage to produce so much for the art market. I don't like to be pushed and put under stress in that way. Certain works also simply need a lot of time to unfold, you can't force your will onto them. It's like a journey. An idea is like a taxi, it takes me only to the main station, but the real trip is with the train, and this train takes time. It's also about all the other things you experience on that journey: the people you meet, the music you listen to, what you read or see during that time, things you encounter by chance, and how all of that interacts with your initial idea down the road.

For me, making art is not about illustrating ideas. I've come across many artworks lately that speak from a postcolonial or a generally critical position, but the way the artists treat the material is actually comparable to the colonial or hegemonial attitude they are criticising. Making art should not be about enslaving your material and submitting it to what you are trying to say. I believe in some kind of evolution, a Darwinian blindness in the working process. You have to listen to materials and sometimes just act as a midwife to what's happening anyway. Otherwise you lose the poetry in your work and it becomes this one-on-one relationship between your material and your position, with no space for an archaeological attempt to dig for yourself with time. The Bell Project took eight years. Not only because I couldn't realise it but because it took years until I realised what I was doing. It's an ongoing process, casting the bell itself was just one of the stations. Its research and working process is linked to What the Barbarians did not do, did the Barberini. Making just one work would be looking past many possibilities that your material offers you. Once you have found your language you don't put it in a vitrine, you speak it.

JM

Your research and practice is grounded in folk traditions, oral histories and direct encounters with the people and places you engage with. Why are these forms so important in the struggle against the combined effort between late capitalism and neoliberalist tendencies?

HKIn my work, I've always liked to play around with little stories, games, puzzles and jokes. It just comes naturally to me. At some point, I learned that there is a term for that: oral histories. This is my language and I cannot afford to talk about complex philosophical concepts. I don't come from that discourse and I'm not an academic. I want people to understand my work. It's also important for me to use a language that people like. We are quite patronising when we talk about Trump being a populist, and so on. To be honest, if I had the chance to speak like Trump in my own work I would be more than happy. There is nothing wrong with that. But we shouldn't leave it up to guys like him.

The present art discourse has become so sophisticated and self-referential that nobody wants to listen or go see an exhibition anymore. People often don't know what's going on when they read texts about art. It's important to have a very simple language if you want people to understand and interact with what you're doing. I happen to have no other choice, I don't speak any other language. I come from a city that is well-known for jokes and funny stories. People from Sulaymaniyah still make jokes and keep their self-irony alive even in the worst situations. Something as simple as ordering a tea in a tea house could become a moment filled with humour. You can address many serious things with a joke or an anecdote.

JM

Rumour has it that one of your installations in Kassel caused major confusion during the run-up to documenta 14. When twenty ochre-coloured drain pipes were dumped right in front of documenta Halle, people believed they were witnessing the onset of lengthy maintenance works in one of the most iconic spots in the city. The pipes turned out to be part of your sculpture When We Were Exhaling Images (2017), and were filled with furniture and various other objects in collaboration with thirteen design students from the Kunsthochschule in Kassel. As you've mentioned, the work is based on a story of refugees who travelled for several weeks inside a truck load of drain pipes. In their attempt to cross European borders, people seek all kinds of routes and hideouts. You travelled yourself in unconventional and perhaps perilous ways from Iraq to Germany twenty years ago. What responses did you get from people who share similar stories of migration?

HKGoing by the amount of selfies that are floating around online, the work is apparently one of the major exhibition highlights [laughs]. I received many images of people living in similar pipes in Chile and India, and various friends and other documenta artists told me about comparable experiences. I'm afraid many visitors only see the story of K who was seeking refuge in one of those pipes in the port of Patras during his trip to Europe. They overlook that the work addresses more than that. For me, it is a way to point at the immense shifts of horizontality and verticality in societies across the globe, and how capitalism is obsessed with verticality and wipes out everything based on horizontal ideas. Unfortunately, the media only represents it as a refugee thing, but it's not. I'm not interested in telling a story about how K lived somewhere—that would be self-victimising. My work always starts with something personal but then leads to addressing something that is relevant on a larger scale. Or at least I hope so.

I've been asked many times why I went for these aesthetics, filling the pipes with furniture and other objects in different styles. All I can say is that it's not only my work. I'm creating a space for students to make their own works and each of them is mentioned as artists and co-authors of the whole thing. The pipes are my work and all the rest is theirs. I spoke with them only about practical aspects and they decided what they wanted to do; they had the last word. That was quite challenging for me because I had to lose control over my own work. It comes as a surprise to most people that a documenta artist would hand over so much power to others, but that's exactly what the work needs. To a large extent it's about their experience to meet and discuss their ideas or simply cook food together; that they live this horizontal relationship.

JMYour sculpture, One Room Apartment (2017) in the courtyard of the Benaki Museum in Athens deals with a related topic. I admit that my first intuitive reading of it associated it with struggles of migration and the economic crisis in Greece and Europe. I only learned later that it is an older work that formulates a tongue-in-cheek critique of the growing individualism in technologically advanced capitalist societies. Can you describe your intentions for the work and how you are presenting it in Athens?

HKIt has indeed nothing to do with migration or the image of the refugee in that sense. But it has to do with the economic crisis, with neoliberal trends and with the fact that we cannot avoid verticality anymore nowadays. As an image, the sculpture is connected to the growing amount of unfinished housing that you see in Athens and all over Greece due to the economic crisis. I wanted to place this image right inside the elegant spaceof the Benaki Museum. I was interested in the visual friction this creates. Seeing unfinished houses in the streets does not make us think about the economic crisis anymore. We are overdosed with images of this or that crisis; we accept them as a given. Placing this inside the grounds of the Benaki kind of brackets the image and accentuates it.

The original idea for that piece came up when I was travelling towards Iran in Kurdistan near Halabja. I saw lots of these minimalistic apartment buildings for singles around there. For me, this architecture is kind of symptomatic of Milton Friedman's famous credo that links the freedom of the individual to the freedom of the market. My project Chicago Boys (2010–ongoing) also takes issue with the fetishisation of individualism in modern societies, especially Eastern bloc countries. Neoliberalism is slowly taking over all aspects of life, it separates people from each other and our sense of collectivity slowly disappears. One Room Apartment just picks out one example for how this is becoming more and more evident in small everyday things. Another one would be the kitchen as a collective space: we used to cook in much bigger pots, now they're getting smaller and smaller.

JMFor the exhibition at KW, you have developed a new cinematic project, The Existentialist Scene in Kurdistan (Raw Materiality 01) (2017), which is conceived as a documentary that traces the formation and subsequent loss of an intellectual subculture in Iraqi Kurdistan between 1970 and today. It does so through the lens of collective agency and the oral histories of several protagonists who played a role within the existentialist scene back in the heyday of Iraq, but are now spread across the globe. Its sixteen hours of footage remain raw and unedited until the work is acquired by someone. Together with you, the new owner can then edit the material from a distant, external point of view. What different things could happen if the work is purchased by an Iraqi or Syrian collector vis-á-vis a collector from a former colonial power or western alliance?

HKI will only give this work to someone from one of the dominating countries in global politics. The core idea of the piece is that Iraq itself, as a country, nation and piece of land, is some kind of raw material that has been edited again and again for centuries by external forces. The same applies to Lebanon or Kuwait. The whole Middle East has been undergoing this kind of editing and reshaping for a very long time. And we all know that the politics behind it are mainly driven by interests in seizing local raw material resources like oil, gas and minerals. The work should go to a collector whose financial investments are involved in these processes. Ideally someone who owns an oil company or is in another way related to the machinery that produces the conflicts looming over the region.

The work forces someone who is involved in the hegemonial powers over Iraq to engage with a culture that they have been indirectly suppressing or destroying. Selling it to a Swiss gun manufacturer is obviously more interesting than giving it only to leftist art institutions. There are five editions of this work for sale and I will be involved in the selection process. Potential buyers will be asked to propose how they plan to edit the material. If I'm convinced I will give it to them. I'm interested in this exchange and in the external view that comes to edit the material. Keeping it as is would make little sense and I would not accept that. I also like the idea that an art collection can be active and flexible. Unfortunately, a lot of this did not really come across in the exhibition at KW in Berlin.

JMYou travel to Iraqi Kurdistan and your hometown Sulaymaniyah on a regular basis. Based on your personal insight into the current state of affairs, what future do you see coming in the next five or ten years for the Kurdish population and the local arts and culture?

HKI'm not very optimistic about the cultural and political situation there. Real estate has been booming in Kurdistan for about ten years now, but it's a small and wealthy elite that takes away all the profits. There are more and more gated communities everywhere and the gap between rich and poor is growing every year. Media outlets and individual journalists are facing censorship, and governmental crackdowns on those who don't comply are increasing as well. There is no change in sight anytime soon because money and politics are in the same hands. At the same time, many other countries play out their own political interests over Northern Iraq and the entire region: Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Germany, Russia and China, or Syria and Iran who are swayed by Russia and China. People in the West are kind of romantic about the future of Kurdistan, but the reality is different. Even Rojava will be most likely defeated in the near future.

I feel more and more like a stranger when I visit Kurdistan. It's supposed to feel like my home, but it has been estranged so much by privatisation and international investments that I can't find my way home anymore—it causes this type of amnesia in times of neoliberalism that makes people lose orientation, which does not come from within but from outside. There is no place that I would call home anymore. That sounds sad but perhaps the idea of having a home is an illusion anyway. I'm not very optimistic in general with regards to the rest of the world either. The amount of migration we have seen happening over the last few years will continue to rise on a global scale. Sooner or later, global warming will make it impossible to live in many regions and fuel the migration crisis. I'm worried about the consequences this will have. —[O]