Igshaan Adams on Mapping Desire Lines

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH Kunsthalle Zürich

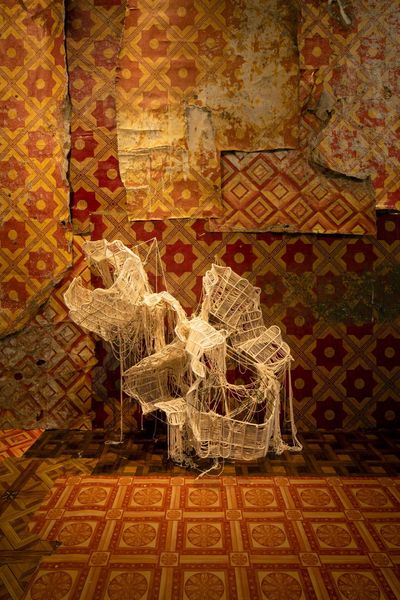

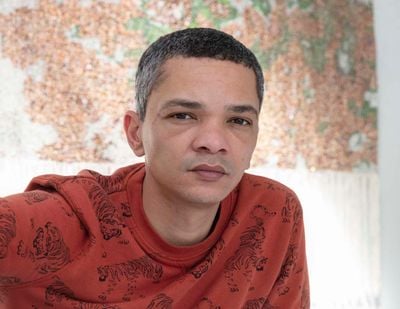

Igshaan Adams. Courtesy the artist and blank projects, Cape Town.

Igshaan Adams. Courtesy the artist and blank projects, Cape Town.

South African artist Igshaan Adams is known for intricate tapestry works that weave personal and collective narratives drawn from growing up in the racially segregated township of Bonteheuwel in Cape Town in the 1980s during apartheid.

As a Creole with Malay roots, an openly queer person, and a Muslim, Adams' practice inquires into his belonging to a community that apartheid legislation classified as 'coloured', forcing such individuals into undesirable parts of the city under the pretext that non-white lives were of lesser worth.

Where circumstances dictated that the best life he could aspire to was that of a shop manager, art-making offered a way out, with Adams studying art and design at the College of Cape Town, followed by a short course in photography in 2005, and a Diploma in Fine Art from Ruth Prowse School of Art graduating in 2009.

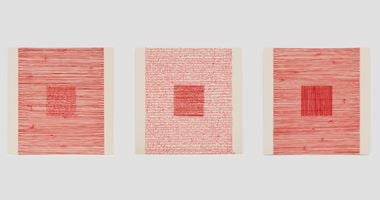

Working across performance, weaving, sculpture, and installation, Adams' multifaceted practice is marked by a process of making and unmaking that draws from topographical research into boundaries and divisions to create elaborate material constructions.

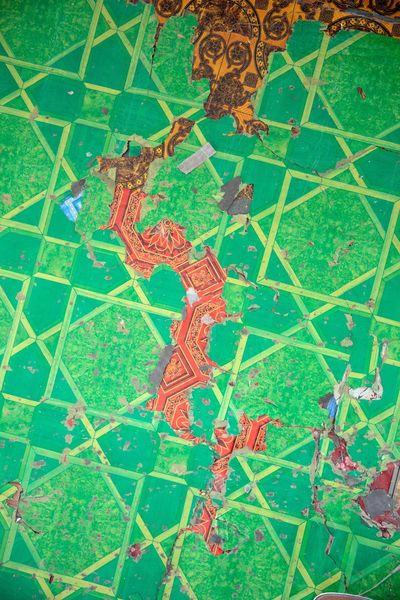

Adams' 2020 exhibition at the SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, Getuie (4 February–8 November 2020)—the artist's first presentation in the United States—lined the walls and floors of the Pamela Elaine Potter Gallery with linoleum flooring from working-class homes in Cape Town, staged besides heavily embellished thread sculptures.

Such cartographies of domesticity were echoed in the nylon and polyester weaving Dwaars Oor (Right Across) (2020), which depicts the linoleum flooring in someone's home, where the material has cracked and worn away after many years of use.

These desolate landscape hinted at the discarding of a past that nonetheless lingers in memory and resurfaces across haunting shapes, sharply contrasting with the tapestry presentation at Casey Kaplan's booth at Art Basel 2021 (24–26 September 2021), where the earth-toned, gridded nylon and polyester tapestry embedded with gold necklace chains, Mapping Yvonne's Kitchen (2021), hung along white walls.

Mapping Yvonne's Kitchen returned a hint of domesticity to the streamlined topography of local regions borrowed from satellite images on Google Earth, which were re-imagined by Adams as residential blocks spread behind patches of green turf. Its presentation followed from Adams' gallery show at Casey Kaplan, Veld Wen (1 May–30 July 2021), where ten detailed tapestries explored notions of 'gaining ground'.

Adams' satellite mappings, which double as blueprints into ideas around life, personhood, and belonging are recovered to expand familiar geographies for the artist's first major solo exhibition in continental Europe at Kunsthalle Zürich: Kicking Dust (5 February–22 May 2022), which follows its presentation at Hayward Gallery in London (19 May–25 July 2021).

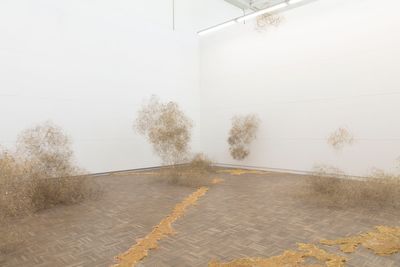

Assembled as an immersive landscape depicting 'desire paths', Kicking Dust replicates the lines that form in the soil following repeated crossing at the racially segregated border of Bonteheuwel and its neighbouring township Langa.

Across the show, hanging sculptures and large-scale tapestries made from diverse but mundane materials—cord, glass, beads, and silk—evoke dust clouds: a nod to the exhibition's title, which references the Indigenous South African Riel dance practiced in Adams' grandparents' Nama community, for which dancers kick dust off the ground.

While the title Kicking Dust doubles as an allegory for art-making—a process that tends to 'throw stuff in the air', as Adams suggests, the artist connects this creative process back to the source reference of the works on view: the desire paths that make marks on earth based on people's movement across it. In keeping, the show is arranged as an open landscape, with viewers able to select their own paths through galleries to form their own desire lines.

To inaugurate Kicking Dust's opening at Kunsthalle Zürich, Igshaan Adams spoke with curator Tarini Malik (now Curator at the Whitechapel Gallery in London), who helped stage the show at the Hayward Gallery, London with Marie-Charlotte Carrier. Below is an edited version of their talk from the transcript kindly provided by Kunsthalle Zürich.

TMThe two spaces at the Hayward Gallery and here in Zürich are very different. What's amazing is seeing the same body of work in very different constellations and experiencing it in a different way.

A starting point is with Kicking Dust, which features a large installation produced for the show. Can you introduce that installation, the process of working on it, and how it started?

IAIt's been such an education working with you both. I've learned so much. It really is a pleasure to see the work function in such a different space; I feel like it breathes here. I see the work for the first time for what it is.

In the Hayward, the setting was intimate, whereas here, with the height and the volume of the space, there's more breadth to it and you can experience the works individually.

Recently I was asked in an interview what the biggest risk I ever took was, and I had to say making the Hayward work, Kicking Dust, in pieces that we put together like a puzzle.

Kicking Dust pictures these desire lines. I used Google Earth to explore the area I grew up in and the neighbouring communities, and in this case, looked at the space between a highway.

I grew up in South Africa in the 1980s, during the last decade of apartheid, so I was classified as a second-class citizen. The community of Bonteheuwel was largely Cape Coloured. Our neighbouring community Langa had a highway that kept communities and races segregated.

This pathway is the grassland between the highway—it became a sign or a signal that people crossed the boundaries. It symbolises hope.

We had to produce puzzle pieces and send them off. The dust clouds we sent as bags of metal candyfloss—I had no idea how the exhibition was going to come together. We had a few days before the opening when we saw the work in its entirety and put it all together.

It was a big risk as it all began in 2020, during the early part of the pandemic when everything seemed so difficult, like determining when to get the works and myself to London.

TMThe central installation was an evolution from some of the earlier works, which are the intricate, tightly woven tapestries on the gallery walls. Those tapestries come from a practice of creating a cartography of an interior space, a home space, which has since progressed to something wider.

I wonder if you can talk about the relationship with the domestic and how that evolved for you to look at these desire lines in an outdoor context?

IAI think it's a natural progression, I would even take it back to before I started thinking about the domestic aspects. I was dealing with the imprint of the body on prayer mats years ago.

I like to think of the first person to take this path, and the others that followed; I hope that as people move through the works, they can feel there is a choice of where to head.

I was looking at Sufi Islam then, which I was keenly interested in; it became a lens through which I see the world. I had collected these prayer rugs that people had been using for decades and on which they had left behind body prints.

They are beautiful and people can project their entire relationship with God onto the rug, so it was very difficult to convince people to give them to me! I've always had an interest in the imprints people leave behind. We all leave some kind of legacy.

I co-opt other people's stories and make them my own, or I gravitate towards groups whose stories are similar to mine.

For a long time, I've been thinking about domestic space as an external space where I can investigate my internal world—my home and the people who contributed to my development. I knew something went wrong. I needed to be healed from the chaos I experienced as a child.

So eventually I began seeing the floor as a map with marks and evidence of events that took place. I started using my imagination to picture what happened and what the marks meant as a document of the experiences of that particular family.

What's beautiful about these floors is that they are unique to each family, even though the materials are common. The floor is easy to get because it is cheap; it has no economic or sentimental value and is discarded annually. People buy it for Christmas to freshen up the house.

Maybe I was attracted to this material because it had no value; I think in a way I saw myself in it. Growing up during apartheid, we were all aware that the aspiration was to be a manager in a shop—for a Black person, it was even lower; your ceiling is to be a gardener or a cleaner.

TMYou are making a beautiful point there, talking about your relationship to interior space and its duality with the exterior.

You mentioned your relationship to a specific form of Islam, which is Sufism. I shy away from the terminology 'mystic', because in the West we have specific connotations with this term in relation to spirituality that can be problematic.

Sufism is a form of Islam that defines so much contemporary practice around mindfulness and expression. Sufi thought asks that you look inside to define yourself on the outside, which explains why the Sufis have such an impact on artistic expression—music, poetry, dance, and song.

That legacy hangs over your work. What you do to an interior space is you monumentalise it. You use its beauty, which is what the Sufis did, as a way to access the everyday, the mundane, the things that are oppressed or overlooked.

It's an exciting and major transition to take this interior-exterior duality in the tapestries and extend it to a broader but related cultural interchange.

What is important for me in terms of reading the exhibition is your experience of navigating apartheid South Africa and the legacies that still live on. Can you talk about your progression as an artist, how art acts as a means for you to reconcile some of the conflicts within your identity?

IAIt's about value. Value for oneself and how growing up, a particular value had been placed on my life that was a lot less than others. That awareness was very strong, so I gravitate towards materials like linoleum and the simple bead, which are quite unremarkable and cheap, in and of themselves. But looking at these materials with the intention of drawing out whatever is within, whatever is hidden. That's me in a way!

I had to dig deep to unlock this in terms of value. I wasn't getting that externally—unfortunately the dynamic of valuing people in relation to skin colour was very active within the home itself.

Within the Cape Coloured community, you had people who looked European, Black, and every shade in-between, and the value system that accorded to these differences. Sufism brought me to a place where I can accept the value of transience and reflection.

TMI love that you use the expression 'brought me to a place' because it suggests a journey, which is a central motif of this show. You journey through the exhibition, on someone else's path. Can you expand on this idea of movement?

IAThe desire line is a pathway created in an open field. It represents going against given structures. You were expected to move through the world according to these structures.

I like to think of the first person to take this path, and the others that followed; I hope that as people move through the works, they can feel there is a choice of where to head. The exhibition hasn't been curated in a linear way with a beginning and end; people become aware of how they move through the space.

Back in Cape Town, I have an exhibition opening at blank projects, where I will show works for which I have again looked at the desire lines on Google Earth, but from up close, zooming in on debris like an investigator, and finding almost domestic details in those pathways and sections.

Often, it's just litter, but sometimes you see where someone might have tried to break apart an electronic object to extract the copper inside, scattering behind leftovers. Looking at these two viewpoints is in a way saying that someone looking at the community from outside will have two different viewpoints.

For that exhibition at blank projects, there is one room where I looked at the pathways from further away, which are so provocative. I tried to think of myself walking those paths. In my early 20s, there was an industrial site on the other side of the train line next to us, where in our most desperate moments looking for money, most of us would go knock on doors for jobs.

It's interesting to see how people's lives change all the time. With weaving, something settles after a while and there's a peacefulness.

I tried to think about what happens internally as you are walking on this path. As you walk with a certain desire, hope, wish, or intention, I started thinking about the nature of prayer—such that not all prayers can be realised, answered, or become reality.

TMThat reflects the ephemeral, mutating nature of the cloud sculpture upstairs. The title of the exhibition is Kicking Dust. The idea of dust is a recurring theme in your work.

Can you talk about the idea of the cloud and the earth being lifted to form this ephemeral matter? Here, it adds something cosmological to the show.

IAI think for some of the sculptures, when you peek into them, they become worlds of their own. In this case, the reference I used is the Riel dance, an Indigenous dance in South Africa that my grandparents would have performed.

What happens with the prayers that are not actualised? So the installation became a cloud in which the prayers are caught—they never actually reach God, who they were intended for. I remember the hopefulness, though the chances were so slim.

I remember as a kid, watching this dance and being mesmerised by something so beautiful, often performed by teenagers or youngsters in pairs. In the dance, they intentionally kick the ground to form clouds. It's called 'dancing in the dust'.

I wanted to have an element of celebration, and this is a joyous dance. Of course, there's also something about these dust particles in the air, which traverse the earth.

TMDust is also made of fragments of human skin and hair and it becomes part of the earth. You have taken something big and philosophical and related to the human condition.

Can you share something about your process making these sculptures? When you installed the sculptures in London, we referred to you as a gardener tending to his roses. There was this wonderful process of pruning and editing and constantly shifting and changing the sculptures.

IAIt's true, I was a gardener for many years, and I can see that. The sculptures need their own time. They can happen immediately, or in other cases, some of the individual sculptures are built up over many years.

Earlier this week, I was trying to count how many failed sculptures were incorporated, some from seven years ago, which started accumulating and eventually formed one thing. Most of these are made up from several failed attempts, which then start taking different forms, whether on the ground, suspended, and so on.

Time is definitely relevant to how they form. I think of myself less as their creator, and more as a carer, who is trying to bring the best out of them.

TMI understand how every sculpture has individuality, a personality, which leads me to the next question. Maybe the best word is not collaboration but communion—can you talk about how your studio works, and the people who work with you?

IAThe studio lends itself to community formation. It's become super meaningful to me, the relationship at home to each person working in my studio. I've become aware of creating an environment and how the quality of that environment influences the outcome and the people.

Everyone's kids come, as often as they can. They are messing around, so there's a certain vibration; there's music playing, laughing, people shouting—my mum's laughter penetrates the whole space.

My two main assistants are women I've worked with for about five years at an NGO in Cape Town, called Philani, which means 'to be well'. The idea was to care for malnourished kids in the poorest part of Cape Town. Early on, they realised they had to empower the mothers to make sure their kids are actually cared for.

My job there as art facilitator was to work with the women and improve their skills and the quality of the product they made for it to sell. When I started employing assistants, two women from that group were the first.

Before that it was my mum, who was my assistant for many years. One of my assistants brought her sister, who had escaped an abusive situation and come to Cape Town. She came in, and then it was someone's daughter, high-school kids, a neighbour—everyone has a relative or neighbour in the space.

My studio manager is someone I have known since I was five years old, his nephew now works in the studio, along with another's nephew. My family also have their own role in the process. My sister and her young girls, I try to teach them everything I know.

Everyone's kids come, as often as they can. They are messing around, so there's a certain vibration; there's music playing, laughing, people shouting—my mum's laughter penetrates the whole space. I love that, which is a bit unusual. Most of my art friends prefer to be quiet.

I have come to appreciate that sense of community. Even outside the studio, there are people I haven't even met, who work on the pieces in Bonteheuwel. Their job is to thread loose beads onto wire to create strings of beads that we can then weave with.

We have these big bowls in which we mix glass, wood, and plastic beads—it's a bit like mixing paint, pigment, or spices. Sometimes we spray them ourselves, and we send them in bags for families to work on.

TMIt's interesting to think about the dynamic and active world you've built and how that translates not only into uplifting and colourful works, but also a meditative space.

IAIt's interesting to see how people's lives change all the time. With weaving, something settles after a while and there's a peacefulness. In the process, you slip in and out of this zone. You can watch yourself doing something.

TMIt's rewarding to experience your work and to understand how many hands and stories are attached to it. People can also relate to themes of policing and displacement. What you create is a means by which you can understand that; you do it through different languages and through beauty, drawing on a vast range of iconographies.

Ultimately, by creating a space in which you have a haptic relationship with the work, you become aware of your own physicality as you walk through, also because of the range of materials. At every angle, you see a different range of materials and colours.

IAThat is the intention—for people to have some experience, some emotional response. That they become aware.

I was doing a workshop with a group of refugees the other day, and I was talking to them about weaving. The first thing you become aware of as you weave is your physicality, your body. Everything shows up. Even with the people I work with, because we have this long relationship.

I have known one of my assistants for a long time, and her body shows her experience—it comes through in the tapestry itself; her strong personality pushes through. If my intention was to create something more subtle I would use another of my weavers who has a more gentle personality.

At the same time, I tell my assistants: if you are late one morning, and you're rushing and in a state, it is not a good idea to sit in front of the loom. Have a cup of tea. If you're weaving it's important that you know how to keep your body, that you are aware of how you're breathing.

Your body needs to be elevated so you are always working at the level of your heart. Weaving takes a toll on your body so the tension in your body will show. You must have an awareness of your physical body and use it to your advantage. —[O]