Inga Svala Thórsdóttir

Inga Svala Thórsdóttir & Wu Shanzhuan, Bird before Peace (1993). Cibachrome CB. 46.6 x 64 cm. Included in the group exhibition Fontanelle, Potsdam (1993). Courtesy the artists and Long March Space, Beijing. Photo: Maike Klein.

Inga Svala Thórsdóttir & Wu Shanzhuan, Bird before Peace (1993). Cibachrome CB. 46.6 x 64 cm. Included in the group exhibition Fontanelle, Potsdam (1993). Courtesy the artists and Long March Space, Beijing. Photo: Maike Klein.

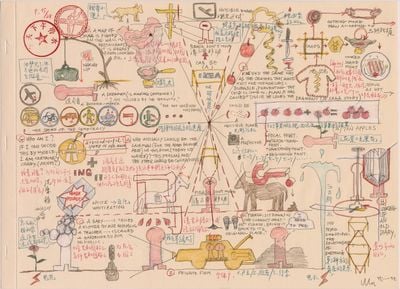

Since meeting in Iceland in 1990, Inga Svala Thórsdóttir and Wu Shanzhuan have developed a cosmic database of signs, words and forms as a result of their continual and unbiased questioning of the nature of things. 'Our studio was basically a piece of A4 paper,' explains Thórsdóttir, recounting the initial years of their collaboration. From this humble format, the artists have meandered from installation, sculpture and photography, to works on paper and canvas as a means of testing and reconstituting our understanding of art and its making.

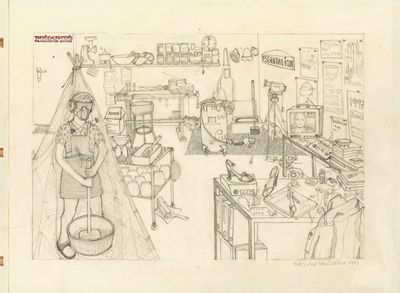

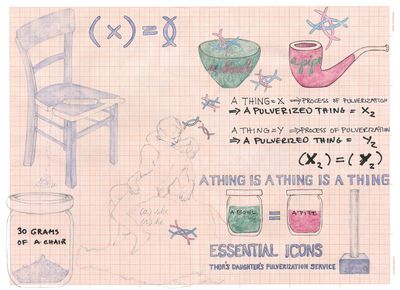

After graduating from the painting department of the Icelandic School of Arts and Crafts, Thórsdóttir studied at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg, where she started 'Thor's Daughter's Pulverization Service' (1993–ongoing): a series in which objects are reduced to their powdered form through a process that involves performance, along with the recording of the pulvarised object through drawing, video, or photography, and each powder's preservation in a 500ml glass jar. A similar act of deconstruction involved a shopping trolley that Thórsdóttir disassembled and packed into a suitcase, which she then brought to Beijing—the uncanny realisation upon arrival being that it may be the first instance a trolley had been imported to China, after the two observed an absence of trolleys in the country at that time.

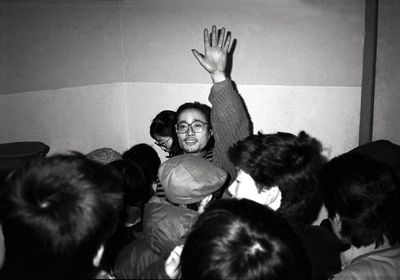

The distinctly conceptual thread in Thórsdóttir's practice found parity with Wu's, who arrived in Iceland to teach before they both went to Hamburg to study at the same university. Wu had already forged a name for himself as one of the leading members of the 1980s pre-Tiananmen Square generation of conceptualists. Graduating from Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts in Hangzhou in 1986, his practice was forged through a series of seminal works including Red Humour (1986), an installation in the form of a room covered with words ranging from advertising slogans to quotations from Buddhist scripture and Cultural Revolutionary slogans—an apt interpretation of the deluge of mass media and general chaos of the time.

Wu's denial of traditional art formats was pushed further in his participation in the renowned China/Avant-Garde exhibition at the National Art Museum of China in 1989, where he set up a stall selling shrimps (Big Business [Selling Shrimps], 1989), only to be stopped by museum officials on the premise of him not holding a business permit.

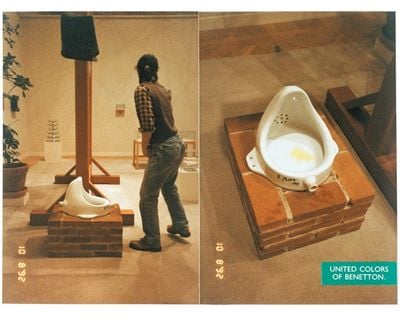

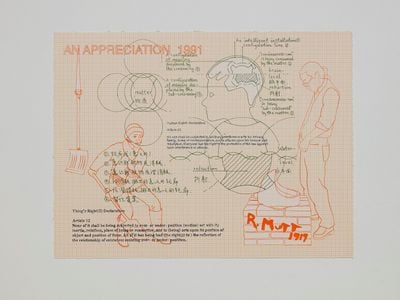

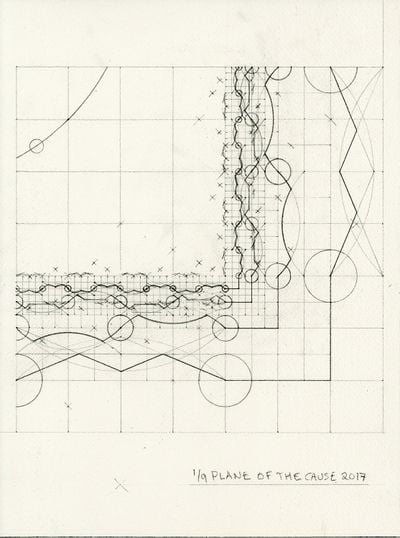

An unrelenting wit has defined the artists' work of the past two decades. Their founding of Thing's Right(s) in 1994, which incorporates both individual and collaborative works by the two artists, came after the two subjected Marcel Duchamp's La Fontaine (1917) to an act they titled An Appreciation (1992) at Moderna Museet in Stockholm, whereby Wu restored the urinal to its initial function and Thórsdóttir photographed the act. The conceptual backbone to Thing's Right(s) has featured throughout their practice, whereby the idea of man as the centre and measure of all things is eradicated to make way for the equal treatment of both genders, among other entities. This all-encompassing approach has seen their work dovetail science and politics, with mathematical references reverberating throughout. The artists claim their discovery of the 'perfect bracket' as a formative moment in their artistic collaboration, whereby two overlapping parentheses provide an absurd negation to their habitual function.

Between 22 March and 18 May 2018, the duo filled Hanart TZ Gallery in Hong Kong with over 290 works for their solo show titled Quote! Quote! Quote!, in which paintings and drawings sat cheek by jowl in an idiosyncratic fury of symbols, signs and forms. Among the frenzy sat Constellation Forest (2018), a wooden structure whose arced shape resembles the vault of a church. With a sense of the infinite radiating from the sheer quantity of material on view, the arced forms condensed the transcendental nature of their practice.

In this conversation, Inga Svala Thórsdóttir discusses the key aspects that drive the duo's artistic practice.

TMBefore your 2018 exhibition opened in Hong Kong at Hanart TZ, the gallery withheld press material. This makes sense, because to provide images beforehand would have been reductive since there was so much making up this show. There was something I found quite sublime about the wooden structure of Constellation Forest (2018), standing beneath the explosion of images and objects you showed in the space; it was like being inside a church. Could you discuss the transcendental, or infinite, in your work?

ISTInteresting to hear—infinity is something we were not thinking about while preparing this show. The point where we found that we had represented the infinite was when we combined the Perfect Bracket (1992) with a spiral and then bracketed the spiral twice. We named the image Kuo Xuan (2011), literally meaning 'bracket-spiral'. The perfect bracket and the whole geometry based on it is the research for the library that we are planning to build.

By installing the Constellation Forest in the centre of the space we were also trying to create a situation for visitors to dwell and stroll through this 'grove', observing the works on the walls surrounding it from different perspectives. I am glad to hear you compare the Constellation Forest (2018) to a church, because we also experience it as a temple. We have been going deep into construction as we would like to build a library in the countryside of Iceland.

TMWhat kind of material will this library focus on?

ISTAfter the repeated experience of being cut off from the internet in Shanghai, I really appreciate the privilege of having books at hand. The idea of possessing books in our contemporary world has become really urgent and comforting to us. Nowadays, the idea of conserving all information on the internet in these clouds is promoted heavily, and people seem to welcome this fantasy. They are buying it and paying for it; our culture is moving really fast towards this madness. For diverse reasons, many world citizens have no access to the internet. In China, the so called Chinese Firewall is a rather abstract term but, in praxis it means that as soon as you physically move into the country you no longer have access to certain data stored in the internet.

We think about the library as an opera or as a symphony containing variations of the perfect bracket and forms created based on it. We are exploring the perfect bracket through the library, so its building material will be varied, and the content will be the library itself.

TMWhat was the run-up to that discovery of the perfect bracket?

ISTThe perfect bracket evolved in the early nineties, when we were getting to know each other and were mainly working on paper. Settling in Hamburg, I was learning German and Wu English. Besides working on Today No Water (2008), a novel that started as a poem of 28 sentences, Wu was also working on a dictionary, which has partially been published.

In the beginning we simply drew the perfect bracket. Since then, we have used it throughout a series of works in all kinds of forms and materials. We were reading some philosophy, thinking about language in general, and we figured that sometimes the annotation notes are more important than the sentence and/or thought that they refer too. After we had put the left bracket over the right bracket, we noticed that this was something really interesting to us—realising that the perfect bracket itself was an interesting 'thing' we wanted to research. While working on the Thing's Right(s) Declaration we decided to use the perfect bracket as a logo for it. This was at the very beginning of our collaboration.

TMCan you give some insights into your studio format?

ISTIn the nineties our studio was basically a piece of A4 paper.

TMIs there a lab-like aspect to the way you go about your work together?

ISTWe work through trial and error and of course our practice includes research, but we do not need much space or material to do our work. Discussing concepts with each other made us autonomous; our dialogue was and is a great support for us both. In general, an artist's community and close friends are very important. Engagement with art can be a lonely occupation and having a companion is a great support, enjoying the practice is the most important thing for an artist.

TMWhat were your artistic paths before you met?

ISTIn 1990 Wu came directly from China to Iceland. He had finished at the Hangzhou Academy and his work was already known in the Chinese art scene. I was in my last year at the painting department but had already started exploring the concept of pulverisation. I did not attend Wu's class but the first time we met we had a long discussion on art and art history—art was our common background. A year later, by coincidence we both got into the Hamburg Art Academy. A great luck that was, for us and our art as well.

TMHow did moving to Hamburg and attending the Academy influence your art?

ISTHamburg and mainland Europe were foreign to both of us. The Academy was the most conceptual Academy in Europe at that time—a great asylum for us.

Back in Hangzhou, Wu had already gotten to know Professor K.P. Brehmer who invited Wu to study without expecting him to attend more classes than he wanted to. Bernhard Johannes Blume invited me to his class, he was an intelligent and generous man. I was no beginner and he also simply let me follow my ideas while observing my work closely. Soon I executed the first pulverisation, A Table and Two Chairs (1992), after convincing the head of the metal workshop to endure my noisy labour pulverising the three things. In the workshop I got the necessary space and tools to do the job—that took me six weeks of hard labour.

TMYou mentioned that there was a language barrier between you and Wu at the very beginning of your relationship. Would you say that this was a determining factor of your explorations into the perfect bracket?

ISTWe had to overcome our language barrier and that meant debating. Our first dialogue was in English—we accompanied it with drawings that expressed the idea of pissing directly into the Marcel Duchamp's Fountain. We later executed the idea at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm and titled it An Appreciation (1992).

Language is continuously developing between people who talk together and actually care about the conversation. Even people who speak their native tongue well from the beginning, their language will become private as they develop their own sense of humour and personal use of language.

Earlier, I said that our studio was a sheet of A4 paper, but sometimes if we wanted to execute an idea we would simply organise a working place for that very project. I would for instance find a studio and tools adequate to the material of each particular object that I wanted to pulverise.

TMCould you elaborate on this concept of 'pulverising'?

ISTMy interest in this has been diverse. Among other things I wanted to materialise an interest in the value and form of things, and labour. The process involves selecting a thing, then observing, drawing and weighing it. Then I find out how to carefully pulverise it and register the method used and the time the labour took. The pulvarised thing is then weighed again, and preserved in a transparent glass and identified by inscribing a label on the jar conserving it.

TMThere is a distinctly reactionary element to the act of pulverising. Was it a conservatism in Iceland that hindered your capacity to develop this idea?

ISTThe concept of pulvarisation was supported in mainland Europe, where evidence of history and civilisation is present everywhere. In Iceland, the harsh nature has demolished almost all traces of the activities of our ancestors and attempts to preserve their accomplishments and things that have been key to survival on the islands through the ages. Hamburg is another world; an organised, civilised, material world, packed with old and new stuff. In Iceland my pulverising fantasies evolved from reading art history and a need to define labour, but in Europe I could use the method of pulverisation to raise various questions while producing a rather modernistic but conceptual sculpture at the same time.

TMIn relation to your use of English, I remember you saying that the necessity to learn Chinese hasn't been there. Would you say also that there is a reluctance to fall into the comforts of language? Might attaining complete fluency between the two of you hinder your artistic discoveries, expressions, and experimentations in a way?

ISTYou put my reluctance to take time to learn Chinese nicely here. Earlier on, we figured it would be just to our dialogue to speak neither Chinese nor Icelandic. We prefer to speak together in our second tongue: English. 'Globish' might be a more accurate term for our common language. A dialogue in a foreign language can be a productive creative space, where new ideas and perspectives can open and be explored. The academically- or politically-correct discourse can be a really a tight corset. Dialogue is a pleasant method to figure something out and the reward might be a revelation. In 1995, we had a show in south Germany at the Bahnwärterhaus, Galerie Der Stadt Esslingen titled Please Don't Move. With this title, we were pointing out that generally any move you make changes your perspective. Being born and raised in different cultures, the various perspectives we bring from our respective cultures is present in our dialogue all the time.

TMAnd you move a lot! How does each country inform your ideas and your artistic practice?

ISTWe live and work in Hamburg, Shanghai and Iceland, in three different countries that is. The languages, the political situation, the nature, the material world of these different cultures influence us in diverse ways.

TMThe sheer quantity of material in this exhibition gives off a sense of urgency. Could you talk about the political aspect in your work?

ISTUrgency, interesting to hear the way you put it—I do not know if I should talk about the political aspects of the work, but I will give it a try and I am talking for myself. Observing the construction boom in China since 1996 up until 2010, it seemed to me that our strict geometric work on the perfect bracket really made sense as an opposition to the arbitrary realisations of mega projects that were being built. The scale, the speed, the immense material used in the realisation of all kinds of crazy projects is greater here than ever before in human history. In 1995, we spent six months in China working on two projects: Showing China From Its Best Sides and MADE IN CHINA, that were first exhibited in Barcelona for the group show, Des del Pais del Centre: Avantguardes Artistiques Xineses at Santa Monica Art Centre in 1995, and later in Hamburg at Kampnagelfabrik K3 for the exhibition Der Abschied von der Ideologie: Neue Kunst aus China.

At that time, Shanghai had started building up the Pudong area. Later, I read that from 1995 to 2000 more concrete was used to build up Pudong than was needed to build Hong Kong from the start. Our stay in China had a great impact on me which later resulted in the project 'BORG' which I have been working on since and was partly on display in the exhibition at Hanart TZ Gallery.

The thing is, if I hadn't worked all this time with Wu in China I doubt that I personally would have put all this effort into the perfect bracket. My drive for working on the perfect bracket was partly because I felt this method is an opposition to the inaccuracy of production and the abuse of material in contemporary China and beyond. The abuse of material and ignorance of the consequences are a frightening contemporary reality. China is a country where a constitution and legal system are not assured, this situation creates insecurity and one feels arbitrarily extradited. In this context I see the perfect bracket as the base of what I call the constitution of our collaborative work.

TMI find a resonance with Hong Kong in this exhibition. In Hong Kong, as a city, there are so many things going on but they all seem to weave into a single fabric.

ISTHow pleasant to hear. I agree, one can describe Hong Kong as a fascinating fabric. We are especially grateful for the opportunity to make this very exhibition at Hanart TZ Gallery. We enjoyed erecting the Constellation Forest (2018) here in the centre of the city, surrounding it from floor to ceiling with our diverse thoughts like a landscape, and in response we titled the show Quote! Quote! Quote!—[O]