Iván Navarro

Iván Navarro. Courtesy Gallery Hyundai.

Iván Navarro. Courtesy Gallery Hyundai.

Iván Navarro needs no introduction once you know what his works look like: light boxes constructed using one-way mirrors to create an infinity room effect.

These object illusions come in many forms, from a world map rendered in green and white lights that seem to collapse into a dark void (Sediments, 2017); to a series of lightboxes formed from the blueprints of various buildings, including the Flatiron building in New York City, in which lights frame a dark void, giving the appearance of depth, with the word 'surrender' legible at the centre (Surrender, Flatiron, 2011).

The idea behind these constructions came in 2003, when Navarro saw a star-shaped mirrored lamp in Chinatown that created the effect of an endless recession into the wall, leading him to devise the standard format for his illusions—using a one-way mirror against a normal mirror, with a light placed between the two.1

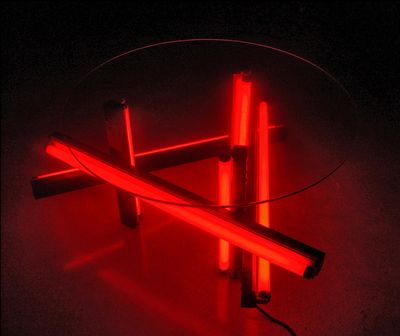

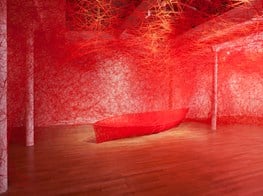

One of the artist's most recognisable series are his 'Drums' (2009–2018), which includes Bomb, Bomb, Bomb (Matte Black and Warm White) (2014), whereby the word 'BOMB' appears in neon curling around the interior of a drum; and Beat (2016), in which the title of the work appears in chunky capital letters. Both of these pieces are currently on view at Gallery Hyundai in Seoul, where the artist recently opened his exhibition, The Moon in the Water (20 April–3 June 2018). Divided across three floors are both old and new works, including three 2013 light boxes whose compositions refer to Josef Albers' 'Homage to the Square' series, and Emergency Ladder (2017), constructed out of red neon lights.

Also presented is Die Again (Monument for Tony Smith) (2006), modelled after Tony Smith's 1962 sculpture Die, a steel box that measures six feet in height, width, and depth. Navarro's version consists of a large, dark wooden structure inside which a pentagram-shaped light sculpture is built into the floor, while an acappella recording of The Beatles' song 'Nowhere Man' featuring the voice of artist Courtney Smith plays on a loop. Navarro collaborates with Smith on 'The Music Room' project, which takes its name from Satyajit Ray's 1958 Bengali film, and manifests as spaces designed for active listening, often of records selected from the archive of Hueso Records, a label that Navarro founded.

Navarro's work is inextricably linked to his experience growing up under the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet—he was born just before the coup d'état in 1973 into what he describes as 'a family of artists'. (His father, Mario Navarro, was director of the graphic design department at Universidad Técnica del Estado in Santiago when the coup took place.) Reflecting on his experience of the Pinochet regime, Navarro's use of light and mirrors alludes to systems of power, and the use of both materials in forms of torture and interrogation during the dictatorship.

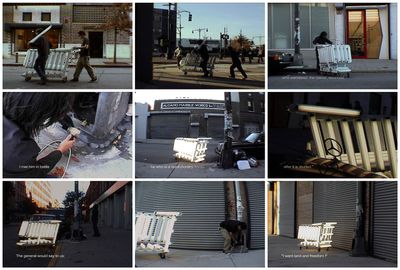

Criminal Ladder (2005), for example, is a 30-feet-high ladder made with fluorescent light tubes for rungs, on which the names of those who committed human rights abuses during the Pinochet regime are listed. The video Missing Monument for Washington, D.C. (2008) consists of two men with bags covering their heads—one stands on the back of the other, who is on all fours, playing a guitar. A voiceover reads the lyrics of 'Estadio Chile', a poem written in 1973 by singer-songwriter Víctor Jara while he was imprisoned (and subsequently killed) in Chile's National Stadium along with thousands of others during Pinochet's coup.

Moving to New York in 1997, Navarro began to actively engage with the principles of Minimalism in order to trace a connection between modernism and forms of control. In the case of his electric chair series, the artist used fluorescent light fixtures to build versions of Gerrit Rietveld's modernist 1918 Red and Blue Chair, a series that started with You Sit, You Die (2002): white fluorescent lights provide the frame for a lawn chair whose paper seat lists the names of those killed by electrocution in Florida between 1924 and 2001. At the 2009 Venice Biennale, Navarro represented Chile, showing, among other pieces, the 2006–2009 installation Death Row: 13 aluminium doors that each create the illusion of a gateway thanks to the neon-lights lining each frame, whose colours matched those used in Ellsworth Kelly's series of 13 monochrome canvases each painted a single colour, Spectrum 5 (1969).

More recently, the installation This Land Is Your Land, presented at Madison Square Park in 2014, turned three of New York's iconic water towers into infinity lightboxes, with one tower featuring 'ME/WE'—a poem that Muhammad Ali came up with in 1975 after a student asked for one. ('ME WE' is also spelled out in Glenn Ligon's 2007 neon work Give us a Poem: Palindrome #2, which is part of the Studio Museum in Harlem's permanent collection.) This Land Is Your Land has subsequently been shown at NorthPark Center in Texas in 2014, Yinchuan Biennale in 2016, Yinchuan MOCA in 2017, and most recently at the Busan Museum of Art in 2018 (6 February–19 April).

In this conversation, Navarro discusses some of the seminal moments that shaped his development.

SBLet's start from the beginning: when did you realise that you wanted to be an artist?

INI grew up in a family of artists. My parents come from a working class background—they were the first ones to go to university and their main concern was education. My older brother Mario Navarro and I went to the same university. The only school that I was accepted into based on my entrance exams was an art school at the Catholic University of Santiago. It was almost as if it was meant to be: as if I wasn't allowed to go to any other school except that one.

So I went to art school and my plan was to stay for one year or six months and then do another test so I could go to another department in another university where I could study set design, which was the closest thing to carpentry for me, since I wasn't interested in visual art—I was interested in design. After a year, the moment came when I had to make a decision about whether or not to stay, and since I had the best time, I did. I realised that I didn't have to be a painter if I stayed in art.

SBFor your thesis project, you only used the materials in the exhibition space, taking the lights down and restringing them into cubes that frame the outlines of fish made using electric cable. How did Camping Day (1996) come into being?

INIt had everything to do with Eugenio Dittborn, who is the best Chilean artist for me. In my third or fourth year of school, a very good friend of mine who was Eugenio's assistant said he wasn't going to work for him anymore, and asked me if I wanted to take the job. I said yes—I needed the money. Eugenio already knew my brother, they had a good relationship and we got along, too, when we met, so I started working for him. That was the beginning—the real beginning—because he wasn't a teacher; he was a professional artist. And an artist that I felt not only close to, but also admired. It was such an honour to get paid for being with somebody like that. I received professional training with him—answering the phone, organising the studio, organising archives, and making the pieces.

Then, for some reason, Eugenio was invited to be the teacher of my class at school, so I became not only his personal assistant but also his student. We managed it so that those two roles didn't clash; everybody knew I was his assistant and was cool about it. He gave us specific projects and assignments every week and one of the assignments challenged us to think about what we could do in a room without bringing anything inside. That's how I started working with lights and electricity, because it was all that was available.

SBSo much is written about how your use of light and mirrors references the Pinochet dictatorship. But I wanted to think about your use of these materials from a different point of relation: an encounter you had with the documentation of Gordon Matta-Clark's visit to Chile, which you have described as a 'eureka!' moment. Matta-Clark came to Santiago looking for his father in the 1970s, and was instead invited to do an installation at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, for which he created a camera obscura in the basement urinal that projected images onto a mirror screen. Could you talk about this encounter?

INThe use of mirrors in my work started in 2004, by which time I was already settled in New York. I felt connected to Matta-Clark, since he was half-Chilean and lived in New York. When I arrived in the city, one of the first artworks that completely changed my perception of things was a piece that Matta-Clark had in PS1, Doors, Floors, Doors (1976), where a large hole was cut through the third, second, and first floors of the same room. I thought: 'This is it'. A year later they closed down that room and blocked the hole because it was a fire hazard, and I had this dream of making a mirror piece in those dimensions and putting them exactly in that location to reference the impossibility of making a hole.

From there, I went on to study Matta-Clark seriously, and that's when I learned about that work in Chile. He was invited to the São Paulo Biennial in 1970 during the dictatorship, and he boycotted the invitation and didn't go, convincing other artists to boycott the event, too. But since he had the money to pay for the plane ticket to South America he decided to go and look for his father, whom he hadn't heard from in 20 years.

SBMatta-Clark seems so resonant in your work, and how your lightboxes are constructed to appear like gateways—that idea of cutting through space to reveal the endless meanings and ambiguities that exist within it, which also recalls Roberto Bolaño, whom you have quoted with reference to the threshold.

Bolaño called the threshold 'the third literary silence' where shadows never get to be tangible facts. This relates to what your works reference by way of composition, and how they essentially explore the murky relationship between Chile and the US through the opaque politics and formalism of Minimalism.

INThere is a critique of Minimalism that makes the Chilean reality part of that criticism, as well as other countries around the world that were affected by the formalism of Minimalism. So, if you take Minimalism as a point of reference, you already kind of have that criticism—it's implied. Because, let's say, there is a group of artists—including Dittborn—in the late seventies, who went deep into criticising the dictatorship in a more subtle way and were very connected to European and American art in a formal way, but not in content. The work of some artists would look just like Mario Merz's, and Dittborn's work would look just like Polke's, but there was clear political content. There are a lot of American and European influences in Latin America, but these manifested just in terms of form, which would then be reinvented with content specific to the region.

SBAmerican Minimalism obscured its politics, but in Latin America, that aesthetic was used to communicate political ideas?

INYes, Minimalism is the art of the Cold War. It's all about machismo, control politics, and colonisation. The dictatorship happened as a result of a collaboration between Chile and the US, and Minimalism is just another representation of that.

SBSo you use references to Flavin and Judd to subvert them rather than pay homage to them.

INSure. Minimalism is the enemy. I wasn't interested in Minimalism, and I've never been interested in Dan Flavin. The only thing that I've really, truly been interested in with Flavin was how he started making work out of survival. He realised this super American idea of consumption in which you go to a hardware store and you can borrow things for 30 days. You pay for them and buy them, but you have 30 days to return them and get your money back. So since his work was so much about readymade objects, he would go to hardware stores where they offered that system, and say, 'OK, I want 100 fluorescent light fixtures', take them to the show, and return them 30 days later, and get the money back. At the time he wasn't selling anything, and that was how he started. Totally out of survival. I'm sure that he wasn't even interested in light, it was what was available, then he thought he'd study light because it was the medium.

SBThis is an interesting way to think about how your practice takes the rules of Minimalism, deconstructs them, then reforms them as gestures of subversion, only to show them at art fairs, and in galleries around the world.

Does working within this global context expand your own understanding of your practice?

INWhat I have experienced doing many shows is at some point you have to contextualise and explain what you are doing, and do a little educational programme. If you are invited to the Cairo Biennial, you have to explain your work, or there has to be a way in which it can be contextualised and have a connection that says, 'this work is coming from this context', it's not coming from Mars. That's one way to do it, and the other way is to look for specific things that I've done before and do site-specific works that find interesting situations in the local context and make connections to my practice.

Showing your work in a place outside the context in which you work is a different process because it has more to do with making your work known and understood by showing what you've been doing for the last 20 years. I'm also not the kind of artist that does site-specific projects all the time; I'm very old fashioned in the sense that I love working in the studio. In this case at Gallery Hyundai, the show is divided into three rooms and each room is about a specific aspect of my work. It's like a little retrospective. Usually I start by getting to know the space, how the space is, and what can be done in the space—what pieces can fit in to it. That's why I brought Die Again here, because it was a good location and the whole show kind of grows from that work.

For me, it is important to do shows where you are able explain what you do so that the work or the practice is not decontextualised, as is the case in an art fair. When it comes to a solo show, the aim is to not just to do something that will sell out easily; that's what art fairs are for.

SBDoes your relationship to a work like Die Again change as it moves through time and space?

INIt took me a while to really understand the piece because when I made it I was much more interested in the idea of repetition and how to make something connected to music, materials, and lights. Later this kind of duality between machismo and feminism became present in the work, too, and I think that lies at the heart of the piece. It's based on the Tony Smith piece Die, which is one of the most important works in the history of Minimalist art. It refers to solidity as the essence of Minimalism and the artist as some kind of genius creator of works that do not really represent anything. It is what it is.

So when I made the work I was interested in how to penetrate a Tony Smith piece. For random reasons, I read about how John Lennon wrote 'Nowhere Man' and what his inspiration behind it was. He wrote it during a moment of crisis. The song is about not knowing what to write, feeling as if all his ideas had all gone. I put the song aside as a portrait of Tony Smith and asked Courtney Smith to sing it. The only material that I kept was the frame, and those are metal, which is the same as the original piece but they are covered in plywood. It's sort of like a tent, in that you can take it apart, it travels, and you put it back together. It has many aspects that are related to how one can build something architecturally and create a space.

But when it came to the idea of penetrating the piece, I wondered what I could do inside it, so I connected the interior to a torture chamber. I made this during the whole Guantanamo Bay period, when inmates there were being tortured with loud music, which offers another connection with Chile, since torture with music was already a practice there in the mid-1970s—I actually made a work in 2005 that was about a specific place in Chile, Venda Sexy, Discoteque Sign (2005), that used to torture people with loud music. So Die Again is also a conversion of that; that's also where it comes from.

SBCould you talk about the form of the star used for the lightbox in Die Again?

INWhen it comes to the star, take the coffee tables that I've made: one is an anarchy sign (Anarchy Table, 2004), one is the Star of David (Joy Division II: Yellow, 2005), and other is a swastika (Joy Division I, 2004). The three are connected as a series that are connected to the new 'Vanity' series (2018), sculptural pieces of furniture meant for houses, as seen here in Hyundai—the idea was not the reference itself, but to have a connection to a historical symbol that has a narrative. I wanted to make pieces that were meant to be used as furniture and charge them with whatever meaning—the same way they had been charged with meanings throughout history. You can use these works as coffee tables, have social relationships with them, and give them your own meaning.

SBThis relates to the words you use in your work, like 'war' and 'revolution'—abstract surfaces in terms of how they can be interpreted. You once said that politics deals with subjectivity as an objective subject—that politics essentially objectifies the subject. Could you talk about how this feeds in to your use of words and the ideas that you work with?

INIt's a narrative. You can use whatever word you want. At the end of the day you're telling a story that is your point of view, and people take it or leave it. It's like literature: the point of view belongs to the author, and the person who tells the story doesn't necessarily have to have a social responsibility for the words they are using. It's fiction. Everyone tells a story, and that's how history is built. So the use of words is basically connected to the ambiguous connection we have with narration, with history and with words. I was very interested in Wittgenstein and philosophical ideas that are connected to perception, conceptual perception, and tautology: super complicated things that are in a way present in my work—in the use of text and light, illumination, self-explanation, and literality. There are layers, and there are pieces where you don't necessarily see these layers, but they are present because they are things that I have always been interested in.

SBHow does this relate to what you've stated about identity as being an important concept for you?

INIt's important because when I moved to New York, the artistic generation before me—like Dittborn and Jaar—were big fans of the South American identity and being victims of the US invasions or postcolonialism. So when it came to identity I asked myself what I could say about identity that these guys avoided or didn't talk about. They were basically attacking the Spanish and the Americans for intervening in their identity, as victims of colonisation. My position was just to move forward. We are colonised, but we also have a life over there. So I started making pieces that were about identity but in the context of a situation where you are in a limbo, and that's where the No Man's Land piece came in. There are three videos that are performances with a sculpture: Flashlight: I'm not from here, I'm not from there (2006) is specifically about personal identity, Homelesss Lamp, The Juice Sucker (2004–2005) is about homelessness, and Resistance (2009) is about national identity.

SBYou've said that your work performs—that each object performs in itself. How does this relate to the performances you stage as part of your exhibitions, like the one you staged at Gallery Hyundai with the band PATiENTS on the occasion of the show's opening, or as part of Fanfare at Galerie Daniel Templon in 2017? Both saw you performing with vinyl records taken from 'The Music Room' project.

I've read that the performance at Galerie Daniel Templon was about revolution, and the music and recordings that you played had to do with revolution; but in Seoul it was about war.

INThese performances are connected to the work I do with drums, which appear in the exhibition space as silent instruments. This is part of the work I do: to remove the original functionality of an instrument and to see how ideas connected to sound can be visualised. So when it comes to making a performance, metaphorically it's to bring the sound back to the instrument.

I'm interested in the history of drums as a war object, and the idea of a marching band as a means to animate a bunch of soldiers that are totally miserable and bored of being at war. The drum set is sort of like a continuity of the marching band. When I did the piece about revolution it was also about war.

SBSo we return to the use of mirrors in your practice, and the idea of looking at something only for it to look back at you as a reflection. As you once said, revolution is violence, and violence is revolutionary—it's a double-edged sword.

INExactly, revolution is a violent process.

SBOn that note, you were going to stage an exhibtion at Izolyatsia in Donetsk in 2014, but had to cancel as a result of the war there at the time. What were you going to do?

INThere was a World Cup in 1973, in which Chile had to play against the Soviet Union. They had already played a game in the Soviet Union before the dictatorship, and I think somebody won. The dictatorship came and the stadium was turned into a concentration camp, but they had to play the game because it was part of the World Cup's schedule. The Soviet Union boycotted, but due to the protocols of the World Cup they had to play the game anyway, so Chile played against nobody—and they won!

My idea was to stage the football game that never happened, give it a second chance and see who would have won. There was theatre involved, because you had to come up with the costume of the players. I had to come up with a Chilean team and Ukrainian team and look for a place, and we had many cool ideas. We would have told people what happened, and then would have made an actual game with a whole artistic and historical reference behind it.

SBSpeaking of historical references, could you talk about the postcards that your father produced in 1973, which were printed on the occasion of Under the Same Sun: Art from Latin America Today at the Guggenheim Museum in New York (13 June–14 October 2014), and form part of the publications on view at your Gallery Hyundai show?

I understand these postcards were the result of a series of Antifascist sessions organised by the National Secratariat of Extensions and Communications at the univeristy where your father worked; part of an exhibition that President Allende was due to open on the day of Pinochet's coup, which was to be titled Por La Vida...Siempre!, or For Life...Always!

INMy dad was a victim of the dictatorship—he was tortured and imprisoned. It took him about 25 years to start talking about it. My brother is sort of half-artist, half-curator, and my dad told him the whole story about these images. Each postcard represents one of 18 paintings that were to be shown in an exhibition that my father was organising: a socialist, educational project that would be staged in 500 locations throughout the country via its network of universities. The idea was to open the same show across the entire country, at the same time, with the same works. Two weeks before the exhibition opened, posters of those paintings were sent to different campuses. Then the coup came before the show opened, and they destroyed everything.

Twenty-five years later my dad received a phone call from a graphic designer who said they had found a complete set of the original posters in somebody's house. They were a little bit damaged because they were hidden behind the washing machine, but it was the only original complete set.

I learned about those postcards only about five years ago, and by then I had made pieces with swastikas that were my most important works at the beginning of my career. It was amazing to find images of works that my father was making in 1973 with swastikas. A work of his also has the same spectrum of colours as the Death Row piece that I showed at the Venice Biennale. It was unconscious, but in the end we were following a similar kind of path. —[O]

1 Hilarie M. Sheets, 'Man of Refraction', Artnews, 26 January 2012: http://www.artnews.com/2012/01/26/man-of-refraction/