Jeff Koons in His Own Words

Jeff Koons. Photo: Cindy Ord/Getty Images for Qatar Museums.

Jeff Koons. Photo: Cindy Ord/Getty Images for Qatar Museums.

One of the most celebrated American contemporary artists, Jeff Koons is currently being honoured with a sprawling survey show in Qatar.

The artist's first solo exhibition in the Gulf Region, Jeff Koons: Lost in America (21 November 2021–31 March 2022)—which was organised by Massimiliano Gioni, the artistic director at both the New Museum in New York and the Nicola Trussardi Foundation in Milan, and the critically acclaimed curator of the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013—features 64 artworks from 17 series produced between 1980 and 2021.

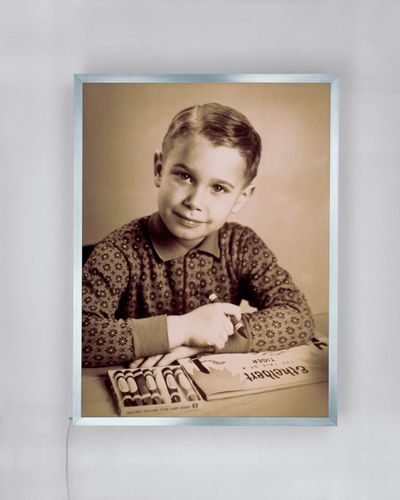

The sensational show, which is on view at QM Gallery Al Riwaq in Doha, begins with a kindergarten photo taken in 1959 of a confident young Jeff Koons holding a crayon in his hand while seated at a desk.

Ironically titled The New Jeff Koons, the 1980 artwork, which consists of a Duratran image displayed in a fluorescent light box, shows the artist connecting with his audience through a highly focused gaze. 'This was at a time when I really felt, or could recognise that I felt, like an artist for the first time,' Koons told Taschen editor Hans Werner Holzwarth in 2009.

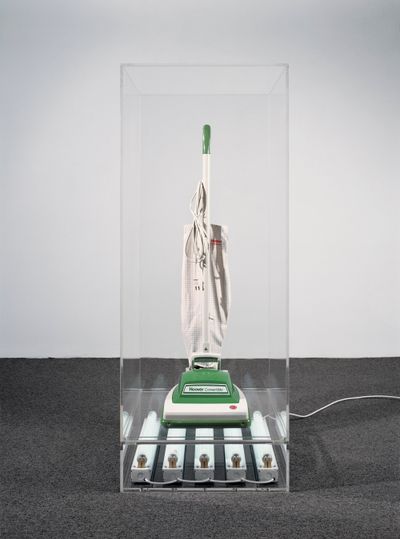

'The exhibition was conceived as an expanded self-portrait, which also doubles as a panoramic view of Jeff's relationship with American culture,' Gioni shared during a preview walkthrough of the show. Koons' series 'The New' (1980–1987) continues with two vacuum cleaner pieces, which display brand new Shelton Wet/Drys machines over Hoover Convertibles in fluorescent-lit, transparent plexiglass cases, and an appropriated printed billboard ad for Toyota Camry sedan, mounted on canvas and presented like a painting. The works speak to the myth of the travelling salesman, who was a family man at heart.

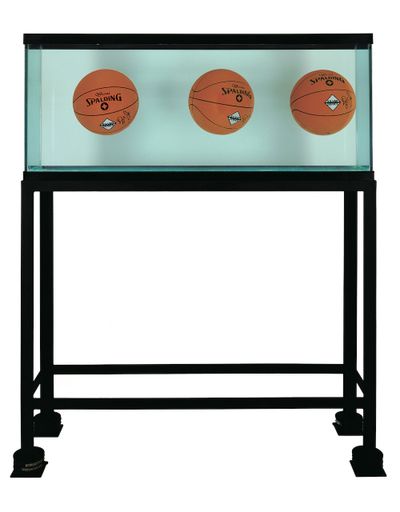

Throughout the 1980s, Koons further explored the Duchampian notion of the readymade. Works on view that exemplify that investigation include his 'Equilibrium Tanks' (1985), which present basketballs suspended in transparent, water-filled fish tanks, and framed Nike posters showing images of athletic success.

Utilising bronze and steel casting, along with wood carving, the transformative sculptural works that followed during that decade explored ideas of a simulated reality, popularised by the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard.

Standout sculptures from this period in the show include Aqualung (1985), a bronze cast of an underwater breathing device; J.B. Turner Train (1986), a stainless-steel casting of collectable Jim Beam bourbon decanters; and Rabbit (1986), an inflatable toy bunny cast in stainless steel.

The latter is his most discussed work of art, as well as the most expensive artwork by a living artist, having sold for a record $91.1 million at Christie's in 2019. Elsewhere, String of Puppies (1988) is a polychromed wood carving of two people holding eight dogs, which was at the centre of a controversial 1992 copyright lawsuit that Koons unfortunately lost.

Works in the show from the 1990s are dominated by paintings and sculptures from the artist's series 'Celebration' (1994–ongoing), which was sparked by a custody battle for his son, whom he had lost yet longed to see, and the 'Easyfun' and 'Easyfun-Ethereal' series of surreal paintings and sculptures involving everyday objects.

Highlights from 'Celebration' are Balloon Dog (Orange) (1994–2000), a massive, mirror-polished, stainless-steel sculpture that took seven years to realise and nearly bankrupted the artist, who was seeking a high level of production perfection, and Play-Doh (1994–2014), a fantastically fabricated, gigantic mound of modelling clay, strikingly realised in polychromed aluminium.

Koons revisits his own youth and an ongoing interest in art history in many of the 21st-century pieces on view. The 'Popeye' (2002–2013) and 'Hulk Elvis' (2004–2013) series utilise cartoon and comic book characters who have overcome the odds working against them.

'Antiquity' (2008–ongoing), 'Porcelain' (2016–ongoing), 'Gazing Ball Sculptures' (2013–2014), and 'Gazing Ball Paintings' (2014–2021) incorporate objects that recall Koons' early life in York, Pennsylvania, where his father had a furniture store and interior design business, which was highly influential on his own artistic development, and reference his love of learning from and participating in the history of art.

'I tease him by saying that only an American artist would dream of making the Mona Lisa bigger than the original, that only an American artist would improve upon the original,' Gioni added, when referring to one the 'Gazing Ball Paintings' in the exhibition.

Like Koons' other canvases, it was realistically painted without a trace of brushstrokes, duplicating the original to show the cracks in the surface from aging. Koons also created his own reflective glass-gazing balls, seeking the style of perfection in their production that he strongly strives for in every one of his accomplished artworks.

PLSo Jeff, how has art defined your life?

JKArt has been the primary vehicle for defining myself as a person, exploring what life can be, what I can become, and what I can share of that experience. Hopefully in becoming a better, vaster human being and to be in dialogue with a larger community.

PLAnd what is the narrative that interests you in this pursuit?

JKIt's about becoming. To enjoy the opportunities we have in life and experience it as vastly as possible, and to share the joy in accepting who we are.

It's also sharing the experience of being part of a community. Celebrating that and celebrating the fragility of life, the momentary quality of it, and the beauty we have to make the next generation's experience even more fulfilling.

Every object we interact with is really just a metaphor for ourselves and for others.

PLWho helped shape that narrative when you were starting out?

JKFrom the very beginning, my family, and then other mentors.

I remember my first-grade teacher, Mrs. Miller. She had one hand—her other arm had no hand, it just had little nubs on her wrist. She could do anything. She was very inspiring to me, and I think that that communicated to me early on that art could let you bypass any limitations.

PLHow did you develop an interest in the representation and display of common objects?

JKI never knew what art was as a child. I did it all the time—drawing, taking lessons, making paintings, and pastels. But it wasn't until I got to college that I realised I knew nothing at all about art or art history.

There was something about surviving that moment that I felt so many people aren't able to be themselves. They become overwhelmed. They feel insecure about not knowing about art, so they don't participate, and then art ends up disempowering, instead of empowering.

Art gave me the ability to accept who I am. I work with everyday objects and things that, at least from my own history, celebrate this moment forward.

Everything is perfect in its own being. That basically means that our own cultural history, whatever it is and what has happened to us, can't be anything other than what it is. So it's all about this moment forward. Every object we interact with is really just a metaphor for ourselves and for others.

PLWhat did the breakthrough series, 'The New', represent to you at the time?

JKIt was about continuing the Duchampian dialogue of the readymade. I was dealing with ultimate states of being and of 'newness' and the idea that these objects maintain their integrity by retaining a state of ultimate being.

Even in the 'Equilibrium' series, there are no permanent states. In the 'Equilibrium' tanks, the 'equilibrium' will last for a certain amount of time and eventually, the basketballs will sink. There is no eternal with us. It's about the interaction with life energy. There are aspects that can be eternal, but it doesn't necessarily mean our lives will be.

PLDo you think 'The New' may have pigeonholed you as an artist interested in commodity culture?

JKI think because I supported myself as a broker it gave people different opportunities to try and put me in that hole whether I fit there or not, because they were interested in commodity culture and defining commodity culture. But I was interested in desire. The desire for our becoming, to be engaged with the world.

It's like when you look at a painting and you feel the energy of the painting. What is important is that energy in the painting is just a description to put us in contact with life's energy. That's really what's relevant—to feel that in our veins.

PLIs it true that the bronze works Aqualung (1985) and Lifeboat (1985) from the 'Equilibrium' series cost you more to make than you were able to sell them for when they were exhibited at the gallery International With Monument?

JKThat's correct. I did that because I wanted to break in. I saved up all my money to purchase the materials to make them. I really wanted to be able to focus on my work all the time. So I tried to make it as attractive as possible to collectors. If it didn't work, I just had to face the consequences.

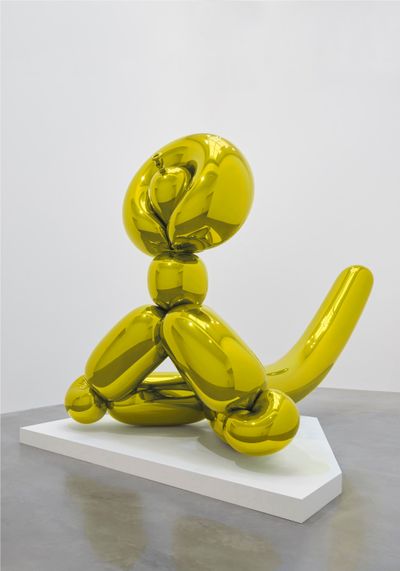

PLYour inflatable sculptures Rabbit (1986) and Balloon Dog (1994–2000), which are based on toys and children's party games, have become contemporary art icons. Where did the idea of casting inflatables originate and how did it become a reoccurring interest?

JKI was a painter when I left art school and moved to New York. I made a painting that was so heavy I had to take it off the wall and set it on a table. I placed two inflatables beside the table; an inflatable elephant on one side and a panda bear on the other.

I started to work with inflatables thereafter. I was placing them on mirrors, but the inflatables would not last. Eventually they'd deflate. So a way to keep them in that optimistic state was to cast them in another material.

PLYou've described art as not existing in the object at hand, but in a person's response to it. Is it because the objects you make are reflective that they provoke a positive response, in the sense that viewers see themselves reflected in the work?

JKI like to think of the reflection as affirmation; that the viewer realises everything really depends on them. If they move, the abstraction of the piece changes. If they don't move, nothing happens.

They could be picking up on something else happening in the environment, but they're really the element that's being engaged. The one interacting with the object.

I like to think of the reflection as affirmation; that the viewer realises everything really depends on them.

Neuroscientist and Nobel prize winner Dr. Eric Kandel introduced me to Austrian art historian Alois Riegel's notion of the beholder's share, which states that the viewer finishes the work of art. Marcel Duchamp was also very much influenced by Riegl's way of thinking.

The artist is involved with the essence of their potential in creating the work of art just as the viewer is involved with the essence of their potential when they're viewing it. They finish the narrative of the work.

It's not about my desire anymore. It's about their desire. I try to bring the viewer to a certain view, maybe to a certain vista, but then they look out and complete the contextualisation of the piece.

PLDo you think the audience's fascination with these reflective surfaces has anything to do with narcissism?

JKWhen we listen to a record, it's a reflection of the music. You never see it associated with the negative. In the visual realm, we can't see anything without light and as soon as you have light, it shines off different objects.

As soon as there's an affirmation of that and it's tied to narcissism, it feels that something's wrong there. There are pressures within the world that have tried to confine the joy in the celebration of visual language.

PLAn experience that changed me was looking at these reflective works when they were shown on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art for Jeff Koons On the Roof (29 April–26 October 2008). I saw myself in the city that I love, reflected in art.

JKI have always enjoyed the notion of reflection in philosophy, too. For me, reflection is a symbol of everything. It's not a coincidence that dealing with an issue involves reflecting on it—to shine a light on something.

PLI've read that you see your Balloon Dog sculpture as a kind of Trojan horse. What led you to this interpretation?

JKI say that because there's more than just the surface view of the piece. Anybody who spends time with the work will have an understanding about it. Again, each situation's different. The viewer finishes the work.

For some people, it will always just be a party-balloon dog. Someone else might look at it and realise that it is that, but it's also the membrane—it's like our bodies. They can feel that. Another person might look at it and say, oh my gosh, this is like the Venus of Willendorf. They might perceive the massive scale and quality, and that it's meeting the needs of a whole community who rally around it.

We are never the same person after we experience a work of art, because we have gene expression. Our synapses change depending on the chemicals that are flowing through them. I became a different person when I really came to an understanding of Manet's work. It's the same way for every other artist that I've interacted with and whose work I have enjoyed. We all have different experiences in those interactions.

PLDo you see your 'Popeye' and 'Hulk' characters as a nod to Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein's appropriation of comic book characters in their work?

JKAbsolutely. It's a nod to the artists. I love making connections. As we were discussing about gene expression, I was very fortunate that I was able to be an artist-in-residence at Columbia University through Eric Kandel, who had won a Nobel Prize for neuroscience, for his studies on how memory works.

The amazing part of that was just noting these connections, the same way that our genes and our DNA are interconnected. If you think of the double helix within our body, in our cultural life outside our body, it's the same type of connection.

By referencing Andy, he's also referencing Duchamp, and Duchamp could be referencing Masaccio. This is our cultural life. Those connections are important. I believe that the only way to find transcendence in life is to find something greater than the self. It's really love that we're talking about.

For me, reflection is a symbol of everything. It's not a coincidence that dealing with an issue involves reflecting on it—to shine a light on something.

It's also this respect for humanism. In certain cultures, showing respect to your elders is beautiful, and it makes so much sense. What art is really doing is trying to connect us to our human history so we can understand the moment we're in and how we can find a way forward that is preferable for our survival and enjoyment of life.

I believe in biological memory and being in touch with the information within ourselves. I think the arts also help us do that.

PLPeople are often critical of the fact that you've elevated toys and kitsch to the level of art. What do you say to the naysayers?

JKWell, there's no way to control that. You can only make the works and try to put them within the context that you've created them.

When I look at my balloon animals, I think about prehistory and people who were working with the intestine of their kill, for instance, and realising that they are making something and that some form of tribal or community gathering can take place around it.

It defines whether they are paying homage to the animal's life after it is deceased. But it's also tied to this meaning of something coming from profoundly within us. A reference to our belly button, our umbilical cord and our internal life, our intestines, but also the interface of our skin to the external world.

PLDo you also have a fascination with kitsch?

JKI have a fascination with the acceptance of everything. I love colours for what they are, and I love materials for what they are, and I love that things are accessible.

There are different objects—such as ash trays—that I have interacted with as a child and that interaction is as meaningful to me as interacting with Michelangelo's David (1501–1504) for someone else.

If that object gave me an excitement and a motivation, an essence of my potential as a child, how could you ask anything more from an object? And so, it's equivalent to David or another great work of art within culture, so I don't believe in kitsch.

I believe that some objects may have more significance to you and other moments of history, but everything's perfect in its own being.

PLIs it true that you considered naming your first child Kitsch?

JKNo. I don't think that I ever really took that seriously. Even when considering that everything is just wonderful and perfect in its own being.

I love objects that sometimes are looked down upon. You can find tremendous beauty in these pieces—in their simplicity of production, their colour application, symbolism, materialism, and even just in their availability.

There's tremendous beauty in everything. The philosophy of acceptance is really what I'm speaking about. I think that my work has been very misunderstood over the years, and I almost have to forgive myself. Why should I think that it should ever be understood at this moment?

In many ways, my work has been fighting that herd mentality about acceptance and about opening oneself up, to show that art isn't a hierarchy.

To a degree, I think we take for granted a certain thoughtfulness that takes time. And even with the amazing artists and writers that we're involved with today, we might not completely look at work freshly because there is a herd mentality.

In many ways, my work has been fighting that herd mentality about acceptance and about opening oneself up, to show that art isn't a hierarchy. And then if we can forget about a hierarchy, a door to a journey can be opened.

PLIn regards to that, your work is often discussed in relation to Warhol and Duchamp, but isn't it also a bit Beuysian in the sense that it opens the door to anyone becoming an artist?

JKI think all committed artists are automatically doing that because they understand the source of their information, which is everyday life. The only thing we have is our life experience. Our interaction with the world. Nothing could become simpler than that.

How we find inspiration is really about opening ourselves up to the pleasures of life and the joys of our interests. I think art is a documentation of that. It's the savouring of life to share with others.

PLIn your Doha exhibition, I was surprised to see works from the 'Made in Heaven' series, which was partially created after your involvement with porn star Ilona Staller. How do you respond to critics saying that the performative nature of this body of work was a vanity act?

JKIt wasn't. 'Made in Heaven' followed my 'Banality' series. I believe the series was the first body of work where I was able to start articulating my intentions. I was using cultural self-acceptance.

It's very much about self-acceptance and opening oneself up to the world. 'Made in Heaven' continues this dialogue of acceptance. I really wanted to show that no matter what our past is, it's all about this movement forward. We're still perfect in our own being, for who we are.

We have tremendous guilt and shame about our past. With that body of work, I looked back to the Renaissance era. I thought about humanism, and again, the dialogue returned to self-acceptance.

PLThe Qatar show doesn't include the more sexually-implicit imagery from the 'Made in Heaven' series. Do you think they see the work as shocking? In retrospect, do you think it is?

JKEverything's about communication, and I've enjoyed the experience of the exhibition in Qatar and the interactions between cultures. I know certain things are dependent on the audience, just as they are anywhere else in the world.

This is the second time that Massimiliano [Gioni] and I worked together on an exhibition. We also had an exhibition together in Mexico City at the Jumex Museum. It was a privilege to have this two-person show with Duchamp. We had almost all of his major works. We didn't have The Large Glass (1915–1923), but we had most of them.

I think that both Massimiliano and I understand working together and we both strive. I give him free reign, but at the same time we're in discussion together. He knows if something's really important to me and we have a lot of trust in each other.

PLString of Puppies (1988), which is also part of the show, is a controversial piece, although most people wouldn't see it as such. There was a lawsuit related to the appropriation of Arthur Rogers' photograph for the sculpture. How did the negative ruling impact your work and your relationship with Sonnabend Gallery, which represented you at that time?

JKIt's interesting, because I grew up on Dada and Surrealism, on Picasso's work, and on making photo montages and embedding collage. When I was working on my 'Banality' pieces, and always with my work, if I ever felt that I should get permission—whether from Spalding, Jim Beam, or Nike—I would.

But when I was making the 'Banality' series, I was taking images and montaging them together and taking black and white photos. String of Puppies, for example, was a black and white photo in a montage that animated the puppies.

I believe that the only way to find transcendence in life is to find something greater than the self. It's really love that we're talking about.

I transformed the photo into a three-dimensional sculpture. I gave it a back. Based on everything I knew about art, I didn't think I was doing anything wrong. So when I lost those cases, I was devastated. I wanted to defend the rights of artists.

I thought that it was important to try to defend my rights, and I did. Eventually these cases did get turned around to a much more positive reception, but there are different international laws. I think an artwork can be a playground for other copyright issues, and that it's being played out sometimes in art when some of the interest really isn't with the ruling but for other areas, such as technology.

PLThat leads me to my next question. Were these early works created with digital technology or through the age-old method of simply scaling up from a drawing?

JKThey were created using very traditional ways, along with slide projectors to make a drawing and then scaled up to get a sense of how big the figure will be.

I've always used technology as a tool. Sometimes, there is pressure to be involved in a dialogue, but I've always felt that one of the mistakes that young artists can make is thinking that technology will automatically make their work new and fresh.

It's wonderful to use tools, but what's really relevant to us is when we can go inward and bring out what's really important to us as human beings. That's fresh. That's really the most wonderful thing, because it makes our moment new.

We find relevance in the moment. The newness of the technology is only a tool to help us better articulate our vocabulary.

PLSo, what led you to use computer compositions when you returned to painting, which you had originally studied in college?

JKI would say it's the same reason that people are involved with different aspects of digital technology and are excited about NFTs. All of a sudden, these things can be very easily made at home.

Dali and Magritte explored working with different overlaps, transparencies, and ways of laying out images. In my view, they really affected the way we look in the 20th and 21st century with the tools that we have.

Picasso was also always very ahead of his time, in ways of looking at overlapping images or how to treat and play with imagery, getting as much information into a painting as possible.

PLWhy are you attracted to the hyperreal or surreal rather than the expressionistic, particularly in relation to the Abstract Expressionist movement?

JKWell, I like emotion and I love abstraction and energy. They're different tools. Just as we were speaking about using different technologies, we have different vocabularies to communicate this type of energy.

If you look at a painting, it's more defined in its shapes and its graphic quality. If you look at an Abstract Expressionist work, with a lot of brushy, blended colour, you are looking at the energy in that painting.

But whether it's the colour or its graphic quality, what we're interacting with isn't energy in that painting. It's the way it's functioning as a metaphor for the energy of life. The energy of life creates and destroys. It has desire and it wants to burst forth and it wants to condense. That's what we're feeling.

That is what's of importance—how to experience more of that, how to be sensitive to those feelings so that we want more and whenever we can feel close to it, to exploit it. That's what's important about those brush strokes and that's what's important about the graphics.

PLIs Pop Art still relevant or are you making something beyond it?

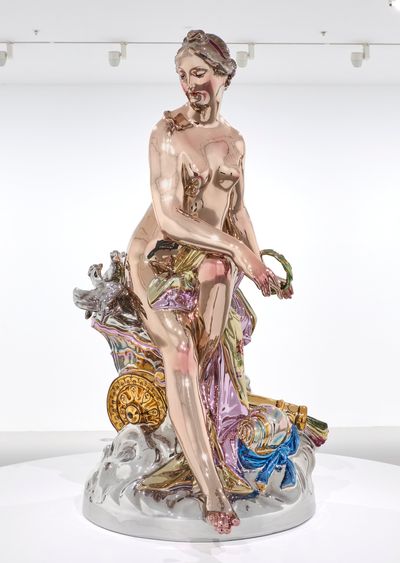

JKI'm trying to make very metaphysical works that connect people to the different sensations of life. There are new works in my 'Porcelain' series that I won't be able to show for two years, but there have been works leading up to it that have been giving a bit of an inkling.

PLDo you ever think that some of the works in your 'Antiquity' series take your embrace of sentimentality too far?

JKI don't really find that series sentimental. Maybe it's romantic—it's the pleasure of having a dialogue with community, of feeling part of something, which in turn opens the door to everyone.

I'm so grateful that art was there for me. And I continued to make art and drawings as a child, but it had nothing to do with the dialogue of what art ended up representing to me. That was just having a certain skill. I felt really quite lost.

But when I was able to have an art history lesson by a college professor who showed Manet's painting Olympia (1863), and spoke about the context in which it was created and the different symbols in it, my life kind of exploded.

I realised that I could be involved in all the human disciplines—philosophy, sociology, psychology, physics, aesthetics. That's where I found meaning in art. Is there a romanticism in that? I guess there is, because I experienced something that gave me, as an individual, a sense of future—that I had something that I could believe in, and I could find a way forward in life.

I felt that I could have self-discovery, because you learn how to create all those things, which takes you to a point where the dialogue with the self is as important as it is with the viewer. You want to be as generous as you can about your life experience.

PLThe sculpture Ballet Couple (2010–2019) looks like a giant porcelain figurine, but it's actually polychromed marble. How challenging was it to make this amazing piece, and why painted marble as opposed to some other material, like resin?

JKThe Ballet Couple is part of the 'Antiquity' series, which I started in 2006. The whole body of work has never been fully shown. I was working with stone because I wanted to work with a material that's profound. It comes from a very deep place within the earth, so it would automatically have that profoundness.

And then to be in dialogue with the ancient sculptors working with contemporary porcelain, but putting it in a material that was used by the Ancients and then painting it in a similar way. If we look at some of the studies that have been done on polychroming, everything was generally painted. Sometimes you have one colour for the flesh or the jacket, without gradations. There's no blending.

The Greek sculptor Praxiteles had Nicias paint some of his sculptures. There would be this glazing of colour, and they would look like porcelain. That was the dialogue that I was trying to connect to, while going back to these other moments in history.

I really love the way you left the base as visible marble, because then it makes you realise that the whole thing above it is marble as well. It's really magical. What would you say to a critic comparing this piece, or your other blown up objects, to the work of Claes Oldenburg?

JKI've always enjoyed Oldenburg's work. I particularly loved his drawings, his idea of making something larger. But I think the 'Antiquity' series is dealing more with scale. In the ancient world, they had large sculptures. You had things of scale—you could even think of the Statue of Liberty as such.

The scale of billboards is just the enlargement of things in the everyday world.

PLAs you pointed out, many other people have dealt with scale in that regard.

JKDid Oldenburg make large pieces? Yes, absolutely. Was I influenced by that? By an artist from the 1960s making large things? Yes, I'm sure.

Where I grew up, there was a man who lived in a shoe house. It was made into an artificial-looking shoe, but it was a house. There were also large neon signs signalling where to go to get pancakes. I think I was influenced more by those things and by antique sculptures.

PLWhere did your idea of employing a blue gazing ball in relation to white plaster representations of classical statues and found objects, such as a snowman or mailbox, originate?

JKIf you look at my Rabbit (1986)—the shiny stainless steel one—and if you look at the head, the head is actually round. For me, it references a gazing ball.

I made the Rabbit in 1986 for a show at Ileana Sonnabend called Statuary. I knew I would have a whole new audience looking at my work and my history working with readymade objects. I had worked with inflatables back in the mid-1970s, and it was a sense of my own history of growing up—this reference to a gazing ball head.

Gazing balls are glass globes. They're round. They're used as ornaments in contemporary culture. They were invented back in mid-1500s in Venice and King Ludwig II of Bavaria re-popularised them. There was even a gazing ball at the base of his bed.

Because there are a lot of Germans in Pennsylvania, I grew up with people having gazing balls in their yards. It was so important to me as a readymade object that I thought for decades what to do with it.

After continuously thinking about it for four decades, I realised that I could work with 19th-century moulds to combine utilitarian objects from everyday life and works from antiquity.

Some of my artworks take years to make, but I wanted to be able to make these sculptures more quickly. The idea of the 19th-century plaster cast was that every city in the world could have their own museum of the highest quality works, and it didn't need to be original—you could have a cast of Farnese Hercules or the Farnese Bull, or Sleeping Ariadne.

That was really the idea, and that the object would be affirmed within the reflective ball—just as the viewer is affirmed, the object falls into the shadows of itself. I was trying to highlight the idea of gazing.

It's really about the pleasure of looking. Where does our understanding of the world come from? I think these sculptures really work in a very minimalist way, emphasising the gazing ball and that it really comes down to reflection. I see the ball as representing everything, and it becomes the universe.

PLBut why do you think the use of the gazing ball on the surface of recreations of seminal works from Western art history is as effective?

JKWhen I made the 'Gazing Ball' sculpture series, I thought I could do a painting series, but then I thought, it's not going to work. How would I do it? I'd have to make a shelf. So I thought, okay, I'm going to make a prototype.

I made a prototype of the Mona Lisa, and I put the gazing ball on this printed cardboard cut-out of the painting. I looked at it and I thought it was fantastic.

The paintings using the gazing ball is one of the most gratifying series for me, because I love the connection with the art, and I love how the ball works like a kind of rabbit's hole. You see the painting being distorted in the ball, and before you know it, you can enter the painting through it.

I love the minimalism. It's participating in the dialogue of the readymade, questioning what art is and what its function is. You look at the ball and it represents everybody.

PLDid you get carried away with this series of paintings? Or were you just really enthusiastic about the range of art history that you wanted to explore?

JKI wish I could have done more. When I say do more, I mean there's a much wider range of our history. That would be fantastic. I actually feel I did too little, because I have only done 50 'Gazing Ball Paintings' over the last seven years. I finished this series, but it's not that many paintings. Many artists make that amount in one year.

PLPeople criticised Robert Motherwell for making too many 'Spanish Elegies' paintings, but in the end, we start to appreciate how different they all are.

JKI think my production has always been quite small. I wish people could just open themselves up to experience them. The reason I'm involved in this dialogue is that I want to open myself up to more things. I can become a greater human being. I can become a vaster artist. I can experience and enjoy life more.

But at the same time I want to share with people what I picked up in my journey of being involved with the humanities over the last four decades, and how art can allow us have a greater life experience.

I wish that people would be more open. We're trying to be supportive of that process so that not only I can open myself up more, but then I can show other people the benefits of opening themselves up and not making judgments, though there are certain forms of judgment that are necessary in life.

It's even the acceptance of darkness, because if you don't have darkness, you don't have light or an understanding of what's dark. Everything is perfect in its own being, and if we are open to that, everything is at our disposal. As soon as we segregate something, we're disempowering ourselves from being involved in using it.

PLMore recently, you've made a leap into the digital with a virtual reality work for Acute Art, and there are rumours that you are working on an NFT. How do you see the future for these new mediums?

JKI think that because of the economics that are involved in blockchain, to cut the confidence of exchange and storage of things digitally, there's a lot of interest in bringing digital art to market. A lot of artists, myself included, have been working digitally for a long time.

If we want to deal with digital images and the digital community, I think the experience of meaning embedded in something would be of interest.

I've been digitising my work for around 20 years. Everything's been digital, but I'm interested in trying to create something that carries meaning, and to show what I enjoy about art.—[O]