Jesse Jones

Jesse Jones. Photo: Peter Rowan.

Jesse Jones. Photo: Peter Rowan.

Dublin-based artist Jesse Jones excavates historical moments of collective resistance and dissent through film and video, using melodrama and Brechtian theatre techniques of estrangement to reignite realities in current social and political landscapes.

Since completing her MA in Visual Arts Practice at Dublin's Dún Laoghaire Institute of Art, Design and Technology in 2005, Jones has created an impressive body of work that has been exhibited internationally, such as her collection of three films, 'The Trilogy of Dust' (2009–2011), which speculate on post-apocalyptic futures, each connected through a series of barren landscapes. The last film in this trilogy, Against the Realm of the Absolute (2011), considers a dystopian future in which the entire male population has been wiped out by the plague.

Filmed in the ash lagoons of Cockenzie power station in Scotland, and in collaboration with a feminist megaphone choir formed by Jones in Edinburgh in 2011, the work explores the connection between feminism and capitalism and speculates on what the world might resemble if this connection reaches a crisis point.

Feminist concerns were the core of the artist's solo exhibition at Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane titled NO MORE FUN AND GAMES (11 February–26 June 2016). The backbone of this exhibition was a 1969 publication by the American militant feminist organisation Cell 16, which Jones used to encourage viewers to shift their encounter with art through a lens of feminist critique.

There is a kind of magic in these thresholds of radical change.

Collaborating with American film composer Gerald Busby to create a new musical score for the exhibition, and incorporating sonic and architectural interventions, Jones transformed the gallery into a cinematic experience that focused on the artwork as instigator of event, rather than as an object.

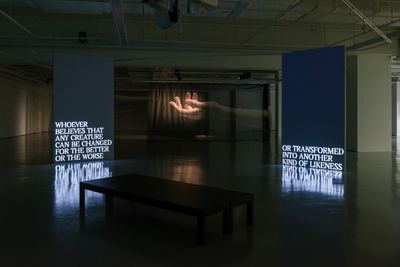

Jones' work regularly takes on a collaborative dimension, as seen in Tremble Tremble, her multi-media installation created for the Irish Pavilion, commissioned and curated by Tessa Giblin, at the 57th Venice Biennale (13 May–26 November 2017). The work consists of a mixture of films featuring Irish actress Olwen Fouréré as a giant performing a script written by Jones, which are projected on freestanding screens, as well as sculpture, a live 'interruption', and a sound score created by Susan Stenger. Tremble Tremble draws from research Jones conducted into how the law transmits memory between generations over time.

The script refers to a 3.2 million-year-old fossil known as 'Lucy' the Australopithecus, an ancestor of the now-extinct early human species; suppressed voices of the 16th-century witch trials; and the legal issue of abortion in Ireland. The resulting installation imagines a different legal order that places the woman's body above the law and state entirely, positing a new world order where the masses are brought together in a symbolic, gigantic body, united by 'The Law of In Utera Gigantae'.

Tremble Tremble was later reinstalled at the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, LASALLE College of the Arts, between 4 November and 28 January 2018: the installation was reconfigured during the artist's residency there in July and August 2017, and was curated by Bala Starr. In this conversation, Jones discusses the history that lies behind the work.

MRWhat can you tell us about the current sociocultural situation in Ireland, now and in the past, which can assist readers in understanding the motivation behind Tremble Tremble?

JJTremble Tremble came out of a feeling of deep political anger over what Irish women have endured at the hands of the Irish state since its formation. In the post-revolutionary period of the thirties, Ireland saw a rise in church and state institutional and political influence. These institutions became synonymous with the abuse of women, as well as the brutalisation of vulnerable people in their care.

The degrading and brutal treatment of women under Catholicism was witnessed in the legalisation of rape during marriage, birth management systems, symphysiotomy, and anti-abortion legislation. Institutions such as the Magdalene Laundries, for instance, were used as sites of forced labour and incarnation of generations of women.

Women were often admitted in these institutions for becoming pregnant outside of marriage. Their children would be taken from them, given or sold into adoption, and the women would be forced to work for free in the laundry as repentance.

Today in Ireland we have a growing social movement that aims to break this bond between the Church and State and move towards a more tolerant and just society. This movement in many ways was instigated through the marriage equality referendum in 2015 and is deepened now in relation to the feminist movement and the recent demand to repeal the Eighth Amendment, which outlawed abortion constitutionally.

These kinds of histories were in the back of my mind when making Tremble Tremble, and it fuelled a sense of anger and a desire for justice against the laws of the State that fed into the instigation of 'The Law of In Utera Gigantae'.

MRThat moment when 'The Law of In Utera Gigantae' is declared is, to me, the most powerful moment in the film. The camera zooms in on the giant's mouth as she declares: 'Before the Book of the Law was written in earthly tongues, there existed another law, passed down through generations, daughter to daughter. Its letters were written in milk and spoken in whispers.' What can you tell us about this?

JJ'The Law of In Utera Gigantae', that the giant declares, is a text I wrote that was gleaned from different places and moments and atmospheres. It was very much influenced by working alongside Mairead Enright, a legal academic and activist. I was interested in how a declaration could function in such a highly public and privileged space as the national pavilion of Ireland.

In a way, that declarative moment references a proclamation of another social order, or even state: a world within a world, which is resistant to the rules of the terrestrial law. The Irish state was forged in this way 100 years ago, when the poet Patrick Pearse, as part of the revolutionary forces in 1916, declared an independent Ireland from British rule. This proclamation became the language spell of a new nation. I believe the speech act has this power: to speak against something is the first moment of interruption of power.

I wanted to create a new law to be uttered in the exhibition space. It's a law that determines the maternal female as giant. A human born to that giant is subject to the laws of the giant.

MRSo, you established the giant's womb as the site of the only true law. Through scale from infant to giant, your fictional 'In Utera Gigantae' suggests that gigantism of the maternal body supersedes all laws. It imagines an alternative original history for women.

JJYes. I have always been really interested in thresholds of change and what happens in culture at exact moments that create the conditions for the transformation of reality. When I was reflecting on how Ireland's anti-abortion laws needed to change, I was thinking about the arguments that were staged at different moments in history on the threshold of that transformation of the law.

I was reading about this moment in Italy and, of course, the famous moment when Simone Veil addressed the French parliament in the 1970s, demanding the legalisation of abortion.

What were the words she used? Could those chants or mantras have been a sort of language spell, casting the listener into a new way of seeing the world? In a way, it is like trying to break down the idea of language as having a potency to affect culture, which is obvious, right?

But what if words were actually a spell that, once spoken, has been cast? There is a kind of magic in these thresholds of radical change. There is more than just the sum of all the parts of societal transformation; there is something else more mysterious that we can feel. Sometimes it is commonly called 'zeitgeist', but I like to think that there is a paranormal political possibility that can be seized in these moments. This is the politics of the witch.

MRThe 'politics of the witch', I like that. And the title of the work, Tremble Tremble, comes from a chant proclaimed by Italian feminists in the seventies, agitating for wages for housework and access to abortion: 'Tremate, tremate, le streghe sono tornate!' or 'Tremble! Tremble! The witches have returned!'

Throughout the film script, you use text from multiple sources, including Malleus Maleficarum (1487) and the oral testimonies of Temperance Lloyd, who, along with Susannah Edwards and Mary Trembles, were the last three women to be hanged in England as witches in 1682. Indeed, at one point, the giantess embodies Temperance, declaring: 'Did I disturb ye good people? I hopes I disturb ye, I hopes I disturb ye enough to want to see this, your house, in ruins all around ye!'

In Tremble Tremble, you seem to restore the witch as a feminist archetype, a disrupter who possesses the potential to transform reality.

JJYes, that was the goal. The Malleus is recited, but only ever backwards—it is used as a repealing of language: to peel it backwards through speech, as a sort of emphasised erasure. I am really interested in this repealing of law and how it motions something in reverse.

The Malleus is often called the most blood-stained book in history, and I was interested in inverting its declarative power and playing with some of the forms of witchcraft and sorcery that the very book accused witches of doing: speaking in tongues and backwards. There is some kind of taboo there, something of the underworld and uncanny.

This was doubly awakening for me as a person coming from a postcolonial Irish historical perspective.

MRI believe Tremble Tremble was also inspired by Silvia Federici's book Caliban and the Witch (2004), in which Federici—an Italian-American academic who links feminism to class politics and the emergence of capitalism—discusses the transition from feudalism to capitalism as being a time of extreme violence against women in the form of the witch trials, and she talks about how capitalism is connected to the dispossession of women historically. Can you explain how Federici's theories also relate to Tremble Tremble?

JJWhen I first read Caliban and the Witch it was a moment of extreme revelation and awakening. Seeing the connections between systems of capitalism and violence against women, and the dispossession of women's power as an economic structural change brought together a sense of class politics and feminism for me for the first time in a very real and actual way. It was the history I had felt but never had the words to express. Federici is so powerful for me in this way.

She offers a way of thinking about the extraction of resources of reproduction from the bodies of women that lays the foundation for all other colonial extractionary violence that was to follow. This was doubly awakening for me as a person coming from a postcolonial Irish historical perspective. The violence is hard to see sometimes, but we have to look at it. We are living in its aftermath every day; we have to know where these structures come from in order to defeat them.

MRThe female giant in Tremble Tremble harkens back to Irish fables of gigantism; were you inspired by those?

JJYes, Jonathan Swift has always been an important figure to me in terms of how he pushed political reality to extremes in order to convey its absurdity and brutality. Of course, Gulliver's Travels (1726) greatly influenced Tremble Tremble. But the simplicity of the giant as a figure of mythic Otherness is a potent symbol in the Irish imagination.

The Giant's Causeway is part of our landscape and Lisa Godson, who wrote a wonderful essay in the catalogue, pointed me towards some examples in the Irish Folk archives that showed how giants were part of our national imagination.

The Irish giant is also a very problematic racial stereotype that was mobilised by the British during the 18th century to emphasise Irish fundamental Otherness. I wanted to look at this complex symbolic figure as an agent, a disrupter of reality—as someone who could speak to our folk collective past, but through a manifest body.

The giant in Tremble Tremble is in the process of becoming a giant; it is something that becomes a form of resistance to the laws of man. In that way, she is similar to Alice in Wonderland, whose body grows and transgresses normative size.

We need allies against the patriarchy; we need allies and companions in our struggle.

Another key influence on Tremble Tremble was a 3.2-million-year-old fossil, the remnants of 'Lucy' the Australopithecus, a specimen of the now-extinct close relatives of modern humans that was discovered in an archaeological dig in Ethiopia in 1974. It's been posited that Lucy was the first humanoid that walked on two legs.

Lucy was a significant influence, as I was trying to imagine a geological version of feminist history that does not conform to the temporal paradigm of first-, second- or third-wave white European feminist histories. I wanted to find a portal out of that.

Developing this ancestral feminist body was a way to think deeper into a timeline of women's experience. She is also overlaid with symbolic references to the Sheela-na-gig—the ancient symbol of birth, death, and fertility.

The story of Lucy in Tremble Tremble aims to open up an origin myth to our shared idea of feminism as a global ancestor, and as a way to imagine the moment before patriarchy took hold. What was female consciousness before that? What was its potential that was suppressed? Lucy is recalling her memories to bring forth the collective memory of this; she is working through a sort of constellation, conjuring the ancestral womb.

MRIn another dramatic moment, the giant is shown attempting to drag oversized courthouse and church furniture with a large rope, as if they are relics from the past, freed from context and authority. Eventually the relics become so tiny, the giant cradles them in her hand, usurping their power. She identifies herself as the Dog Woman. Who is she?

JJThe Dog Woman for me is a mixture of two different archetypes: Hecate, the three-headed goddess of magic and witchcraft who is often flanked by loyal dogs, and Diogenes, the exiled philosopher of ancient Sinope who always has a faithful canine companion.

This idea of the relationship between dogs as companions of the dispossessed is also very compelling to me. As animals, they have a sense of honesty about them; they can cope with the most basic conditions once there is love and food and shelter. This feels honest in a way.

Do you know that book by Mikhail Bulgakov, The Heart of a Dog (1925), in which the conflict between the idealism of humans and the corruption of society are told through the transformation of dog into man? It's incredible; satire can really drive the knife into the truth.

In Tremble Tremble, Dog Woman is a response to the relationship between women and dogs and the proliferation of the word 'bitch', taking the archetype of the dog through history and turning it into something powerful, as a co-subjectivity with woman. We need allies against the patriarchy; we need allies and companions in our struggle.

Developing this ancestral feminist body was a way to think deeper into a timeline of women's experience.

MRAt various points during the film the two bone sculptures are illuminated. What can you tell us about the two sculptures and how they relate to the work?

JJThe two sculptures were a way to make a physical manifestation of an image I had in my mind of the bones of Lucy the Australopithecus. I wanted to have them feature in the installation as physical evidence rather than an image. They are cast from Jesmonite and are drawn in and out of the scene of the installation with the lighting. They are both elbow bones, which felt important as symbolic of the manual and the arms of Lucy, and how women's arms are connected to labour and the maternal.

MRAt one point during the film there is a live 'interruption'—performers enter the installation space pulling a scrim with an image of an arm around the room. What is the significance of that moment?

JJThis moment is a sort of heralding of this new world order of 'In Utera Gigantae', when the performers insert the body into the space—both with the large moving scrim images of Olwen's arms and with their own bodies. It is a moment of manifestation; the gesture reminds us of a march or a trade union banner; some form of cloth of scale and significance that might be dragged through the streets.

The importance of the movement of the screen began as a territorial claim on the space; it herds people, creates a pathway through the space that often is disruptive. The move into the space embraces the viewer, too.

These giant material hands aim to echo the maternal arm of the mother, and perhaps trigger our first cognition or memory of our experience with that. They are both menacing and comforting. I have always been interested in Brechtian stage directions but these arms are more of a way to expand the cinematic frame outside the space of the projected image.

MRThe work was reinstalled at the Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore between 3 November 2017 and 28 January 2018. Can you tell us about that?

JJThe iteration of the show in Singapore included two new sculptural elements. The first was a steel-burning table, which contained the burnt remnants of copies of the 1821 repeal of the Elizabethan sorcery act of Ireland. This object references the Hungry Ghost Festival of Singapore, in which once a year the souls of the dead awaken and walk the earth. They are offered gifts and burnt effigies.

This transaction between the living and the dead ensures prosperity in the afterlife for ancestors and, by extension, for the living.

I wanted to make an offering to the 28th generation of women who have lived and died since the very first witch was killed in the European witch trials. It is speculated that we can trace the first official witch burning from the Valais trials of 1428, in which the accusation of sorcery led to a systematic persecution with hundreds of victims executed.

It is approximated that we have had 28 generations of grandmothers, mothers and daughters since then. I wanted to honour this ancestral line of survivors by sending them the repeal of this brutal law. The hungry ghosts would be freed and, in turn, would create good ancestral will towards the further repeal of oppressive laws against women today.

The second sculpture features six hammers used by an Irish missionary brother, Joe McNally. The objects are relics that connect the living and the dead; they stand in for the non-present bodies of the dead. Relics are powerful in this way; maybe this is a residual Catholicism, but relics have always felt talismanic to me in this way. With every iteration of Tremble Tremble, I plan to add ingredients, sculptures, and potency to the spell.—[O]