Joe Bradley on Process and Finding the Balance

Sponsored Content | Galerie Eva Presenhuber

Left to right: Joe Bradley, Midnight (2023). Wood, metal, light bulb. 59.5 x 23 x 38 cm; Joe Bradley. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich/Vienna. Photo: Gertraud Presenhuber.

Left to right: Joe Bradley, Midnight (2023). Wood, metal, light bulb. 59.5 x 23 x 38 cm; Joe Bradley. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich/Vienna. Photo: Gertraud Presenhuber.

Over the past two decades, American artist Joe Bradley's style has varied so wildly that headlines announcing his re-invention seem to be the only consistent aspect of his career. All that transformation has worked out for him—despite resisting market pressure to maintain a recognisable aesthetic, Bradley has become one of the most prominent painters in New York.

If Bradley had a conceptual constant, it would be the way he treats the Western art-historical canon like a Rolodex of references to be called on: the legacy of gestural Abstract Expressionism is evident in his large-scale, raw canvases; nods to Primitivism and Arte Povera are visible in his scrappy, graffiti-like drawings; and his early monochromatic paintings—hung on the wall in groupings that recall the blockish shapes of robots—appear distinctly Minimalist.

Those 'robot paintings' were the first works to gain critical attention. Although Bradley was already a notable figure in the New York Lower East Side art scene (having moved there after graduating from Rhode Island School of Design in 1999), the paintings turned heads when they debuted in his first exhibition at Canada gallery in 2006.

Bradley was later invited to exhibit monochromes in the 2008 Whitney Biennial and at MoMA PS1 (2006). Since then, his work has continued to be exhibited in major galleries and museums around the world, appearing newly metamorphosed with each show.

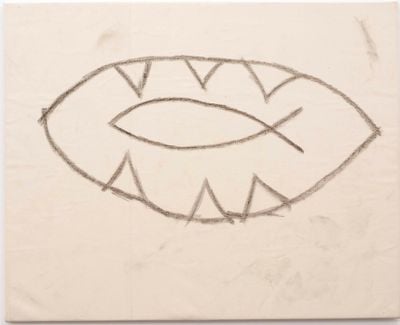

One of Bradley's most notable bodies of work is 'Schmagoo Paintings' (2008)—a series of cartoonish grease-pencil drawings on canvas. The works, when exhibited at Canada in New York in 2008, were described by the gallery as 'a waste of time to try to understand and a pleasure to pursue.'

This double-edged response seems to be characteristic of the reception to Bradley's work: Bradley is going to do what he wants—and he's going to have a good time doing it. It's not hard to imagine Bradley smiling as he flips through art history books, dog-earring and tearing out pages at will.

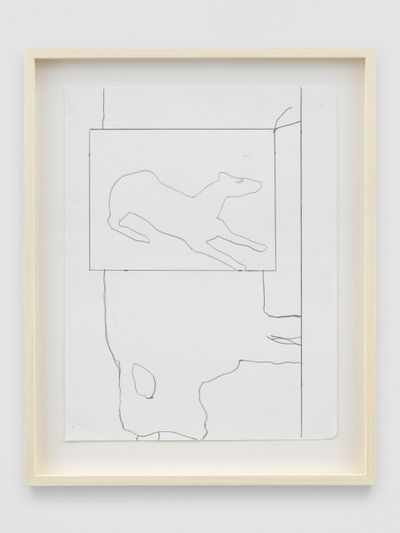

On view at Galerie Eva Presenhuber in Vienna, Bradley's current solo exhibition Rejoice: Drawing and Sculpture (21 April–25 May 2023) combines the old with the new. Several of the cheeky, playful, and untitled drawings in the show—dating back as early as 2006—resemble doodles of nudes or line drawings of dogs, while others look like geometric studies for robot paintings.

In another room are several figurative sculptures like Liberation (2023), which comprises a wooden lightbulb and plaster sculpture of a man's head. Belying Bradley's characteristic humour, Vehicle (2023) consists of a red-painted wooden car with a totemic, bodyless head at the wheel.

On the occasion of the show's opening, Bradley spoke with Ocula Magazine about humour, process, and the balance between the sacred and profane.

EACan you tell me about the title of your show, Rejoice: Drawing and Sculpture?

JBThe working title was just Drawing and Sculpture, but that sounded a little dry. So, Rejoice.

EAThere seems to be an air of humour in the works.

JBI hope so.

EAThis show doesn't have any paintings. Why did you make that decision?

JBI visited Eva's gallery in Vienna maybe a year ago, and I loved the space. It's three smallish rooms with an arched doorway. The paintings I have going in the studio wouldn't have worked—the scale was off. But the sculptures and drawings felt appropriate.

EASeveral of the sculptures, such as Liberation, Despair, and Midnight (all 2023), are quite figurative. Are they of anyone in particular?

JBNo. The body is very much present in these sculptures, but it's meant to represent a sort of generalised human form. Despair and Agony (2023) touch on suffering—the ordeal the body goes through in life. Liberation and Midnight point to the transcendence of suffering.

EAWhere do you find ideas for the content of your drawings?

JBI keep a lot of source material around the studio—books, old magazines, comics. So I might grab something from there to get the ball rolling, or just pick up a pencil and go.

EAIn many of the untitled drawings, you've drawn boxes around the subject matter. Why?

JBIt's a framing device—a way of locating the edge of the drawing while the thing is in progress, rather than relying on the edge of the paper.

I like the way it looks because it draws attention to the edge. A lot of action happens around the edge of the picture, particularly in painting. It feels like the place where things can kind of go sideways and fall apart.

EAWhat do you do if it falls apart?

JBYou just have to keep working at it until it feels shored up.

EAYou've said that you know a work is done when it feels like it's not really your own—like it's a bit foreign to you. Could you elaborate?

JBThe idea is to get the work to speak for itself—to have a life of its own. I can accept a painting that I have made as 'mine', but I don't want to see myself in it. In the end, it's not about me.

EADoes the same feeling apply to sculpture and drawing?

JBYes, but I don't arrive at that place in the same way with sculpture and drawing. It's a totally different approach. My paintings tend to unfold over long periods; when I go to work on a painting, I may be responding to a mark that I made six weeks or months ago. My drawings come together very quickly, I might make 20 drawings in one sitting, and then throw out all but one.

The idea is to get as much into the work as you can. See what the work can tolerate.

But sculpture is totally different. The sculptures are a combination of things that I've made, found, and fabricated. I join these elements to create something that I hope feels whole and authentic. But it's not about my hand. It's about letting the world in. About being out in the world, looking for the right thing.

EAOver the years, critics have talked a lot about you re-inventing your practice. Do you go through periods of transformation?

JBI think so. Early on, there were some pretty dramatic pivots. One show would look nothing like the one that came before. I found that exciting, but didn't want to give the impression that my work was about these changes, that it was some kind of performance. At a certain point, I decided to slow down and focus on painting, which has a natural tempo of its own.

EAWhat caused those early pivots?

JBThe first show of my work that got any real attention was at Canada in New York [Kurgan Waves, 2006]. It was a bit of a lark because I had thought of those stacked monochrome paintings almost as a side project. I wasn't imagining that work sustaining an entire career. But no one else knew that, so when I did shift gears, I think it came as a surprise.

EAYou've said that you need to lose contact with a painting to be able to deface it. How come?

JBThere's always a point in the process of making a painting in which you become attached. You know the painting isn't cooked, but you develop a sort of affection for it that makes it difficult to move forward. This is when you need to work up a bit of courage: you have to destroy what may be a decent painting to get to the promised land.

EADoes it feel risky when you do that?

JBOf course, there is no real risk involved. It's just art in the end. Maybe you lose a painting.

EADo you still paint on the ground?

JBMostly upright now.

EAHas that changed the work?

JBI think it's changed the way the paintings look. I still work on the floor in the early stages of a painting. I find that in working flat, it's easier to get lost in it. I don't get bogged down in composition. It feels a bit more free.

EAThe exhibition text for Rejoice states that your works contain both 'the sacred and profane'. Do you agree?

JBI hope so. That is life, right? The whole catastrophe. The idea is to get as much into the work as you can. See what the work can tolerate.

EAWhat about it is sacred to you?

JBArt or life?

EAAren't they one and the same? But yes, art.

JBArt is a celebration of life. I have a friend who is a scholar studying the history of war, I don't know how he does it! A life in the arts—we are so lucky. It's such a sweet way of engaging with the world.

Looking at history through art, you are encountering humanity at its best. I just spent an afternoon in the Bruegel room at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Talk about sacred and profane! It's all in there. —[O]