John Yau Connects Three Asian American Modernists

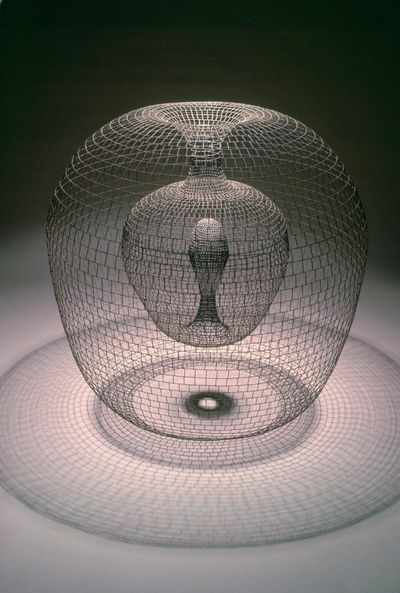

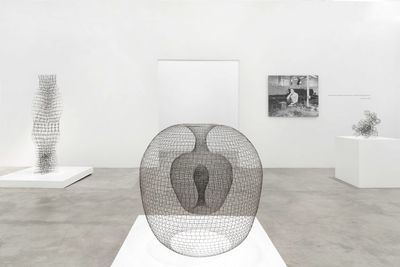

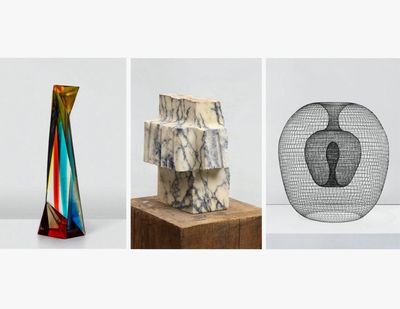

Left to Right: Leo Amino, Refractional #184 (1983). Polyester resin. 22.2 cm; Minoru Niizuma, Unknown (c. 1986). Italian Paonazzo marble. 49.5 x 34.3 x 29.8 cm; John Pai, Involution (1974). Welded steel. 102.02 x 102.02 x 102.02 cm. Courtesy Tina Kim Gallery.

Left to Right: Leo Amino, Refractional #184 (1983). Polyester resin. 22.2 cm; Minoru Niizuma, Unknown (c. 1986). Italian Paonazzo marble. 49.5 x 34.3 x 29.8 cm; John Pai, Involution (1974). Welded steel. 102.02 x 102.02 x 102.02 cm. Courtesy Tina Kim Gallery.

There is still so much work to do when it comes to re-writing canonical art histories, so that re-assessments of artists once side-lined might expand the legacies that they in part shaped.

Poet, critic, publisher, and teacher John Yau has contributed to this expansion at Tina Kim Gallery in New York, with a show bringing together sculptures by three 20th-century Asian American modernists—Leo Amino, Minoru Niizuma, and John Pai—who each taught in some of New York's most revered institutions: Cooper Union, Pratt Institute, and Columbia University.

The Unseen Professors (18 November 2021–29 January 2022) is a rich triangulation. Each sculptor maps biographical and artistic cartographies spanning East and West, which intersect in New York City at a time when exemplary figures of Minimalism and the postmodern avantgarde were making a name for themselves.

The oldest of the group is Leo Amino, who was born in Taiwan in 1911 under Japanese occupation and came to the United States in 1929, first landing in California before moving to New York and briefly studying direct carving with Chaim Gross at the American Artists School in 1937.

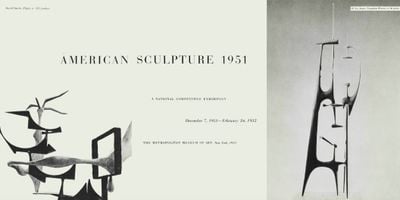

Amino was a contemporary of Isamu Noguchi, and exhibited alongside him at the 1939 World's Fair in New York. After the attack on Pearl Harbour, he was made to translate for the Navy. When the military declassified polyester resin, Amino began to use the material in his work. He would become, as stated by David Zwirner on the occasion of Amino's first solo exhibition there curated by the artist's grandchild Genji Amino (The Visible and the Invisible, 6–31 July 2020), 'the first artist in the United States to use plastics as a principal medium for experiment.'

After the war, Amino became one of the most featured artists in the Whitney Museum of American Art's Annual show, with his fluid forms garnering institutional and critical acclaim. His stunning 1951 polyester and resin sculpture Winter Scene recalls the stretched interlocking forms of, say, Noguchi's Kouros (1945) or the sinewy figures of Wifredo Lam's 1943 painting The Jungle.

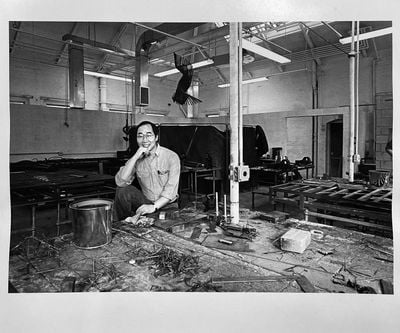

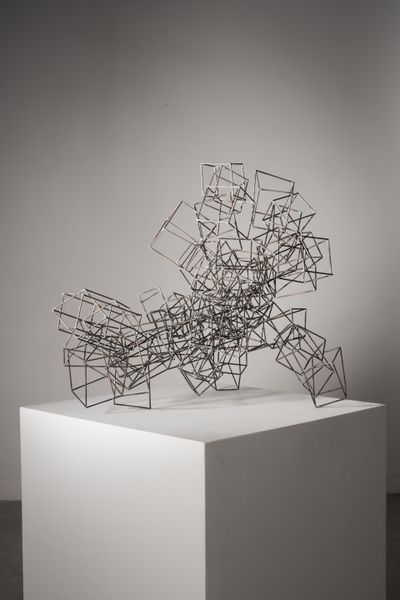

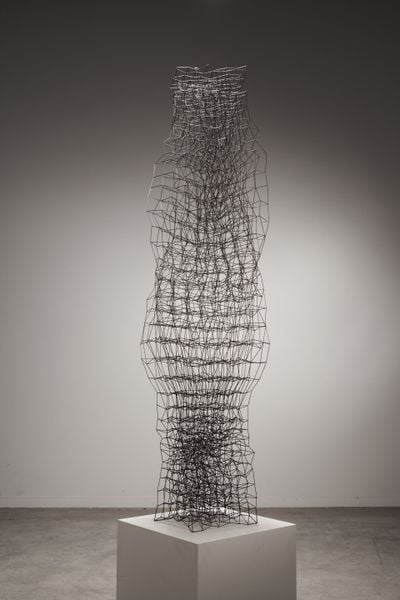

Where Amino explored light and space through the voluminous transparency of resin, John Pai uses welded steel rods, at times coated in copper, to create drawings in space; whether in Lost in a Finite Space (2011), from which a grid is shaped from a spiral form, or in Aspetuck (2008), a column created from a wave of rising steel.

In these works, steel lines reflect an intuitive scoring that manifests as fine scaffolding, building shapes the artist works out as he goes along. 'Working is like a private ritual', Pai has said. 'It brings me back to the idea of reaching a communion with a sense of silence, finding my way within and without it.'1

Born in Seoul in 1937, Pai immigrated to the U.S. at age 12, where he developed his artistic practice quickly, staging his first solo exhibition at age 15 at the Oglebay Institute in West Virginia, later becoming the youngest ever professor at the Pratt Institute while studying for his MFA in sculpture there, after graduating in 1962 in industrial design. By 1965, he was named Undergraduate Chair of Pratt's Sculpture Department.

In contrast to the material lightness of Pai and Amino's sculptures, Minoru Niizuma, who arrived in the United States in 1959 from Tokyo, where he was born in 1930, worked in stone, creating shapes that engaged with nature as a conceptual root for solid geometries.

Niizuma tended to work in series, the most notable being 'Castle of the Eye', characterised by cubes, often arranged into columns, whose surfaces are scored by square lines gradating to a central point, with a 1964 marble version housed in the MoMA collection.

In Portugal, where the artist returned often after first visiting in the 1980s as part of the Evora Symposium, a pink marble version rises up from a lake in the botanical gardens in Monteiro-Mor Palace, Lisbon. It is one of Niizuma's many sculptures from the series found in the city—among them, a monumental cube from 1987 positioned at the entrance of the Gulbenkian Museum.

In bringing the works of these three sculptors together, The Unseen Professors seeks to redress an oversight. In particular, Yau cites the essays 'Specific Objects' (1965) by Donald Judd and 'Sculpture in the Expanded Field' (1979) by Rosalind Krauss, which engaged with minimalist sculpture but did not mention any sculptors of colour.

'By gathering together a group of sculptures made of different materials', writes Yau, 'this exhibition will demonstrate that there was a group of artists who had roots in other histories and philosophies than the one that was narrowly defined by Judd and Krauss.'

In this conversation, Yau shares some of the things he's learned about Amino, Niizuma, and Pai in the process of curating this show, contextualising their practices within the context of art in America in the 20th century, and reflecting on what their stories mean today.

SBFirst thing's first. How did you come to focus on these three specific artists for this exhibition in New York?

JYThe first artist I discovered was Leo Amino, whose work I saw at a show at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University, where I teach. I knew of Amino's work from the 2015–2017 touring exhibition, Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933–57, curated by Helen Molesworth, but I had not seen a lot of Amino's work. The Zimmerli show opened my eyes.

The second thing that happened was that John Pai invited me to see his work, as the Korean Cultural Centre was planning a show of them for 2022 in their new building, which is still under construction. I took the train to Westport, Connecticut where Pai is based and ended up writing about his work for Hyperallergic.

These three artists had a faith in modernism—that exploration could lead them somewhere and they could make something that embodied the complexity of their experience without being anecdotal.

At a later point, I told Tammy Nguyen, a Vietnamese American artist, that I wanted to do a show about these two sculptors, and she told me about Minoru Niizuma. That's how the three came together in my head.

Then I told Tina Kim my idea. Three sculptors, each working differently and in different materials, all Asian, all teaching at a university in and around New York city, all working in the 1960s. But they're invisible, even though they were all in major shows and in major collections. It seemed like a discrepancy. Tina said she would have the show at her gallery. That's how it came about.

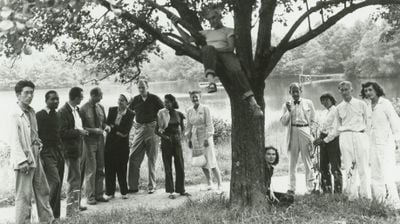

SBThere's this amazing photograph of Leo Amino at Black Mountain College, where he taught in the summers of 1946 and 1950, and you have Jacob Lawrence and the Albers in the frame. It's incredible when you learn about his story. He was a contemporary of Isamu Noguchi.

JYRight. And he showed with Noguchi in 1939 at the New York World's Fair. In that photo, when Jacob Lawrence was there, it's because Josef Albers invited Jacob Lawrence and his wife, the artist Gwendolyn Knight, to teach at Black Mountain and provided a car to drive them so that they would not encounter any racism from New York City to the south. And during their time there they never left campus.

Amino was hired after World War II when the Japanese were not looked at favourably. He did not have a college degree, and at Black Mountain College, it was Albers, a German immigrant, who gave him a job, who understood his situation. That all fits together in my head. Who hired these people? How did he get his break?

SBAll of these things thread together, don't they? That's the complexity when you look at the full breadth of the development of art in America in the 20th century.

JYRight. A little-known fact: for the photos you see of Yoko Ono's performances, Niizuma is the photographer.

You see these little connections between one Asian and another. John Pai got a job at Pratt, where he was the youngest professor there and he became the centre of a community of Korean artists, writers, and composers, because he was the only person with a job and his wife is a great cook.

He had parties in his house in Brooklyn, and so many people passed through; novelists, musicians, and artists, including Korean artists living in America, such as Nam June Paik, and Korean artists visiting the country, such as Kim Whanki and Kim Tschang-yeul.

You get a sense that there was a whole Korean art world with everyone supporting each other, and that this world was separate from the white mainstream art world. While Pai had shows in Korea, he was relatively invisible in New York; but he had a support system in New York that was not of New York.

We know there was an art world in Harlem, but we have not yet recognised that there were other art worlds in New York at the same time. And they were modern artists working with their own traditions while at the same time working within the American tradition.

They were between two cultures or in one that collapsed together different beliefs. That's what I am trying to call attention to.

SBIf you look at figures like Noguchi—or his contemporary, the American dancer Sono Osato or even Si-Lan Chen, who was the daughter of Eugene Chen, the first foreign minister of the Republic of China, and Nanyang painter Georgette Chen's husband—and the nature of the time they came of age, they embody complex cartographies. They become a part of a history that is very unique but also embedded in much bigger stories that connect so many different parts of the world.

JYWhen it comes to work by non-Western artists in Western art criticism, it's so often about something looking like something else . . . rather than about seeing and understanding a work on its own terms.

SBI was wondering if you could talk more about this, as you researched these three individuals. What micro and macro histories emerged for you?

JYAll three took a different route to get to America. There was no migration or surge. John Pai's father was a minister who studied in Chicago. He was in the American army during World War II.

John Pai was born in 1937. He did not see his father until he was eight. When Korea was divided into two countries in 1948, his father and mother—who was raised in Russia, knew Russian and Korean, and played the piano—decided to bring the family to America. They came on army transport.

On the way from California to Wheeling, West Virginia, they stopped in Ohio and a friend who owned the place where they were staying, said to John's father: 'You're in America now. Your children should have American names.'

And suddenly his name became John, and his sister's name became Mary. When they arrived in Wheeling, John Pai's father soon decided to return to Korea to fight for Korean liberation. Soon after, John's mother went to help John's father in that fight. Essentially, they left him in Wheeling when he was 15.

SBOn his own?

JYOn his own. He was raised by a Christian American family, and only discovered being Korean later in life.

In this situation, he decided to be a football player because he'd be part of a team where he could prove his athletic abilities, and people wouldn't bully him.

SBIt's a classic story, isn't it? That desire for assimilation.

JYExactly. And then Pai realised as he went along that he wasn't going to assimilate.

As an artist, Pai has shown a bit in New York, but he has had a bigger career in Korea and not in America. Yet he was the undergraduate Chair of the Sculpture Department at Pratt. I mean, there's some discrepancy there, and you have to learn to negotiate that. I'm really interested in how people came to New York and negotiated that situation.

Take one of the Korean artists that Pai knew, Kim Tschang-yeul, who is best known for his trompe l'oeil paintings of water droplets and who learned how to airbrush by painting ties in a factory in New York City for a dollar a tie. Early on, he painted some of his water drops with airbrush techniques, but soon realised he preferred making them with a brush.

This is a history. About negotiating life in another country in a language you don't know well as an artist. What do you do? How do you survive? Ai Weiwei did it, living in the East Village. So did Leo Amino.

Amino learned how to carve wood by working in a Japanese wood importing place in New York, and taking wood back to his room. He developed his practice as a self-taught artist. Robert Ryman did that too, with painting. Then Amino learned how to cast plastic, because he saw it being used. That's how open he was. But what artists could he be put in relation to?

Donald Judd more than likely saw his work because the conceptual artist Dan Graham put Amino in a show at his gallery, which gave Sol LeWitt his first solo show, but chose to ignore it.

Everyone from a certain group of the New York art world would have gone to that gallery: Judd, Dan Flavin, all these people. So when Amino debuted his plastic work, he was the oldest person in that show and no one seemed to notice.

Then Vito Acconci wrote about him a couple of years later in a review of a show in Artnews. At the time, Acconci was a young artist working in the avantgarde tradition that Judd helped define, but he never gave judgment about Amino's work, just a description.

So that's about as far as Leo Amino got. His work was described, but the Minimalists did not want to recognise his accomplishment. I want to call attention to that—that you can be seen in New York, but be invisible at the same time.

Yet while Amino, Niizuma, and Pai did not attain that kind of critical authority, they did get authority from teaching. One thing I discovered is that Amino taught night school because he wanted to work in the studio during the day, and one of his students was Jack Whitten. Whitten said it was Amino who introduced him to direct carving.

SBWhat else did you learn about the impact that these artists had as teachers?

JYThat's the next step of research. The only one that I really got was the Jack Whitten connection with Leo Amino. I feel like there are probably more connections that I will have to dig deeper to find and see who was studying at Columbia University during the time that Niizuma was there.

I am also curious about how Niizuma knew to talk to Yoko Ono once he got to New York City; there must have been a communication network, associations, and none of that is known or written about.

SBI suppose that's what this exhibition is about: opening research paths for others to follow.

JYExactly. On that note, I want to mention Georgette Chen, whom you wrote about. I only discovered recently that I'm related to her. My grandfather on my father's side was the first Chinese person to graduate from the University of Bristol.

Chen's mother, who died in a freak accident in Riverside Park, is related to my grandfather and to Georgette's mother. Georgette's father is related to my mother's side of the family. So I am related to Georgette through my father and my mother.

My mother's family was involved with supporting Sun Yat-sen and the founding of the Republic. Her father was the foreign ambassador to Belgium under Sun Yat-sen and later was chancellor of Nanjing University.

SBI feel like these stories are all connected; all driven by forces of change taking place amid the two World Wars of the last century. A lot of the people from Asia, and elsewhere, who ended up in the United States, and beyond, were connected to their own cosmopolitanisms, and there was a spectrum, too.

Chen was the daughter of a wealthy internationalist, while her husband Eugene's father sold himself into indentured labour in the West Indies after fleeing China following the crushing of the Taipeng Rebellion.

JYRight. It was and is cosmopolitan, but most people don't understand that aspect of Asians who came to America because they often hold a narrow view of what Asians are like.

They were between two cultures or in one that collapsed together different beliefs. That's what I am trying to call attention to.

In terms of art and New York City, I feel like the art world focuses on Asian American artists who are somewhat tragic or are seen as slightly loony, like Martin Wong and Ching Ho Cheng, who died of AIDS, Matthew Wong, who sadly committed suicide, or Yayoi Kusama who returned to Japan and committed herself to an institution.

That seems to be the New York view of Asian artists. They are either dead or mentally tortured. I don't think it's intentional, but that's a focus that has emerged.

SBWith that, could you walk us through the show and how you placed works in relation to one another? What struck me was how each artist interrogates volume and space but in very different ways.

JYThey do interrogate volume and space, basic issues in sculpture, in different ways, but they also explore light. Take Amino's plastic sculptures; it's something you see through but it's solid. You walk around it, the colour changes. It's prismatic. And it's also geometric.

Then you see Niizuma's column pieces. Partially inspired by Henry Moore, he wants the column to be both solid and something pierced that you can see through.

What we have are artists dealing with major formal issues like solidity and light; solidity and porousness. With Niizuma, he's also carving stone, which in the Japanese art tradition is not a major material when compared with ceramics or ink painting.

It took me a while to see this in his work, but one of the things that Niizuma does is take the veining of certain stones and plays with it. That is an extraordinary way to look at stone and a different way of looking at nature. That is his innovation.

In the West, you put the thing in nature and dominate it. But Niizuma's stones are often rough on one side and smooth on the other sides, almost as if they've broken off from something larger. There is this sense that Niizuma is aware that nature will always take over; that time pulverises everything in the end. That's a different way of looking.

SBIt reminds me of Kim Lim, an obvious comparison to make, in which the geometries of nature are distilled and formalised into sculptural form. These are not shapes for the sake of shapes.

JYRight, and she was often the only woman and Asian included in group exhibitions in England. Both she and Niizuma interact with their materials in a way that's not Western.

It's a different tradition that the West has still not been able to acknowledge. The Asian tradition of nature, where time wins over everything, is completely opposite from the Western tradition, where time can be conquered.

No one seems to talk about that dialogue in the art world, at least as far as I can tell.

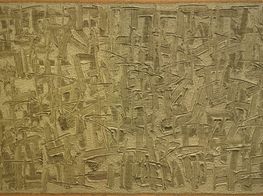

SBThat makes me think of Dansaekhwa, which I see as a form of action painting, of gestural abstraction, though I've had debates with some American critics who disagree. Take Ha Chong-hyun, who pushes paint through burlap. Just because they are not as vigorous, say, as a Jackson Pollock, those paintings still document a very physical process.

JYRight, and calligraphy is gesture writing. That kind of painting comes from a long tradition that the Western framework often doesn't make space for.

SBWhich brings us back to this show, and its intention to broaden the scope of modernist trajectories in the American context by approaching it from an Asian American perspective.

JYWhat we have are artists dealing with major formal issues like solidity and light; solidity and porousness.

SBI would love for you to speak to this, because something happens to individual 'Asias' once they enter the United States and become 'Asian American'.

For example, bringing together mid-20th-century artists from Japan, Korea, and Taiwan means something quite different in Asia, given the histories of Japanese colonisation.

But in the context of America, you have Amino, who was persecuted for his Japanese connections amid World War II, and who stood against anti-Japanese racism in the United States.

JYDefinitely. I've talked about it with friends. Whether Vietnamese, Korean, or Chinese, historically, we shouldn't all be sitting in the same room having a nice time. We should be arguing with each other. And we laugh about that. But I think most people who are not Asian would not get the humour.

If you look at each artist in this show, they had to negotiate both their own histories and coming to, or growing up in, America. What does that mean? Some people forget where they come from, and some people always remember.

I think for all three of them, it wasn't about escaping or leaving behind their histories after they came to America, or forgetting them or becoming nostalgic about it. It was about finding trajectories forward and through them, which is really important. They tried to figure out how to make something modern without forgetting that they carried with them traces of a different culture.

SBThis goes back to what you had said about the West not knowing how to deal with Asian philosophies, cultures, and experiences as conceptual underpinnings for formalist work.

The work of Amino, Pai, and Niizuma could be read in the same vein as Noguchi in this light. Formalism was appealing to artists like Noguchi because it was about manifesting unity in disparate conditions.

JYRight. But then formalism in America—embodied by the likes of Greenberg and Donald Judd—ignored these vital cultural differences. They don't implicate themselves in a messier, more complex field of references. They acted as if there is only one avantgarde tradition. But there isn't.

The Gutai painters were not copying the West. They were inspired by the West, but they were deeply rooted in Japanese history. Yet somehow no one could accept that until years later. I mean the Gutai were only 'discovered' by the West in 2005!

SBAnd Dansaekhwa a few years later, technically.

JYExactly. But modernism didn't just happen in the West; in Paris and New York. It was a global experience. Many societies had to deal with becoming modern and they had to figure out what that means.

SBAnd it went both ways. The 20th century was a time of modernisation that took place across the world, spawning different legacies and roots of modernism that was shaped by and across cultures and disciplines.

JYExactly right. I feel like that's something that's only starting to come into play now. We are only starting to acknowledge that.

SBWith that in mind, as a scholar who has engaged equally with the American art historical canon and histories of Asian American art, how has curating this capsule exhibition informed your understanding of global modernisms?

How would you place these artists in an expanded history of American modernism that incorporates the contexts in which they operated and were connected?

JYThat's a good question. I think their work has to be placed in the same room with other artists to see what the conversation is. But somehow that's not happened.

They tried to figure out how to make something modern without forgetting that they carried with them traces of a different culture.

I once wrote an essay called 'Please Wait by the Coat Room' (1988) about the placing of Wifredo Lam's The Jungle in the entrance of the Museum of Modern Art, near their coatroom, and their response was to take the painting down.

The museum could not acknowledge that they had misrepresented Lam when they wrote that he was 'the first Surrealist to use ethnic sources', but you just have to keep pushing. Lam was Chinese and Afro-Cuban. His grandmother was a Yoruba priestess.

I feel like Amino should be seen with the Minimalists. All of these people are very formal, as you say. They're all aware of reductive tradition, they're all aware of abstraction and they come to it in different ways. But they enrich the tradition of abstraction through the different responses they had to different materials.

In an interview that's never been published, John Pai talks about David Smith liking big slabs of steel, and wanting to work with the opposite, to work with the line. He said David Smith thought of steel as solid, but he thought of steel as liquid. That is a very different response to this material that is thought of as indestructible.

It's so smart that Pai said it. It's the total opposite of how we see steel in American sculpture. You could say it comes from an Asian sense that nature is a condition of change and transformation.

And there's so much patience in Pai making one short rod at a time. Pai didn't know how sculptures would look until he finished them. That's a lot of faith, and that's the other thing. These three artists had a faith in modernism—that exploration could lead them somewhere and they could make something that embodied the complexity of their experience without being anecdotal.

SBThat sense of faith reminds me of how Noguchi reached for modernism as a means to establish a new way of being that echoed his belief in America as a land of all peoples and nationalities; where a new kind of globalism could evolve.

JYIn the case of Amino, Pai, and Niizuma, I believe that all three of them believed that America gave them a certain possibility that they might have had in their own country. And that there was a way they could become themselves and America would accept them.

In a way, they weren't necessarily disappointed. Each got attention; they each got a certain kind of success. It would be different than what Americans think is successful because Americans have a grander vision of success. But I don't think the three thought they were failures.

SBTo sustain an artistic practice through your life is noteworthy in and of itself.

JYI know John Pai well. He has a family. Raised two children. He's done well. He says he's been able to have a studio this whole time; 'What more do I need?'

When it comes to the work of Amino, Niizuma, and Pai, I've had to address the implicit and overt racism that kept their work out of history. But you can't make a glacier move faster than it can. You have to nudge it along.

SBThat is what's interesting about this exhibition's return to legacies of modernism within the current context.

Noguchi tried to find form at a time when it felt necessary to reconceive what form could be—as he himself grappled with his identity as bi-racial, Asian American, and Nisei. It was about taking that language of form, of purity, to redefine it.

There was lot invested in an engagement with modernism from that perspective. While there is a history of racism wrapped into this history, it is also couched in optimism, or idealism.

JYAbsolutely. That's why I didn't want to insist on the racism. My essay says it's there, but I don't make a point about it. I think if I did, everybody would stop thinking about the show. I wanted to bring it up, but I didn't want to make that the focus.

These three artists persisted despite these things. None of them overtly complained about it, as far as I can tell. It was just another obstacle in the road. And it was sometimes ambiguous. Like the time Niizuma was included in a Japanese art show at MoMA, which on one hand promoted Japanese artists but on the other segregated them from the American art world.

I thought about that a lot, because I know that in the 1980s the sculptor Luis Jiménez was torn when he was invited to participate in a Latin American show because he didn't want to be pigeon-holed.

He was like, 'I don't want to be in it. I'm not a Latin American artist. But I should be in it. I am a Latin American artist.' He finally decided to be in it because it would be good for younger Latin American artists to see that he was in the show.

SBI know artists from the Arab world who had that exact problem in the last decade; who declined to be in exhibitions focusing on contemporary art from the Arab world because that framing would precede the reading of the work itself.

JYYes, they would be segregated and exist in an aesthetic ghetto. When it comes to work by non-Western artists in Western art criticism, it's so often about something looking like something else—the work by an artist that belongs to the Western canon, or that can be associated with a Western frame of reference—rather than about seeing and understanding a work on its own terms. How it stems from different trajectories, philosophies, and conceptual underpinnings.

This makes me think about the poet and curator Frank O'Hara, who said about second-generation abstract expressionists that just because their work might look alike doesn't mean that they are the same. He said we should see and attend to difference. He's right. It's our responsibility. —[O]