Julie Mehretu on the Right to Abstraction

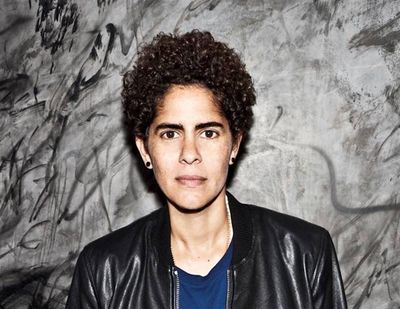

Julie Mehretu. Photo: © Anastasia Muna.

Julie Mehretu. Photo: © Anastasia Muna.

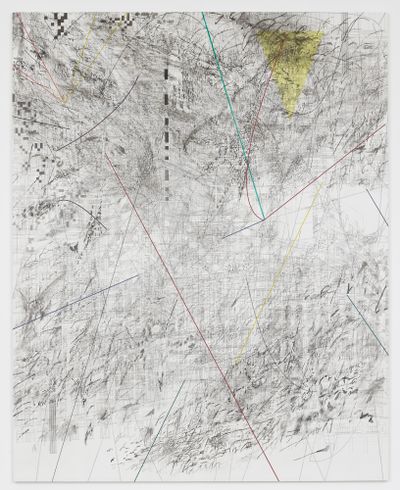

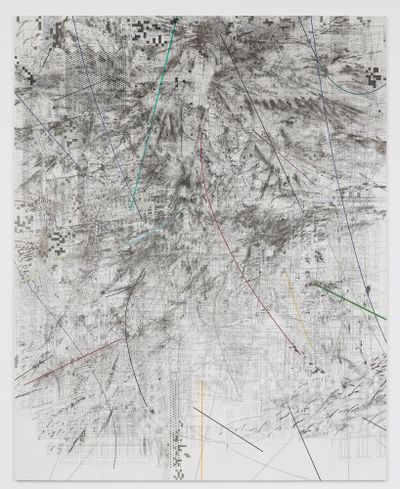

Julie Mehretu's mark-making has evolved in the past decade. Her sweeping architectural lines, marks, and symbols have undergone a deep study and evolution.

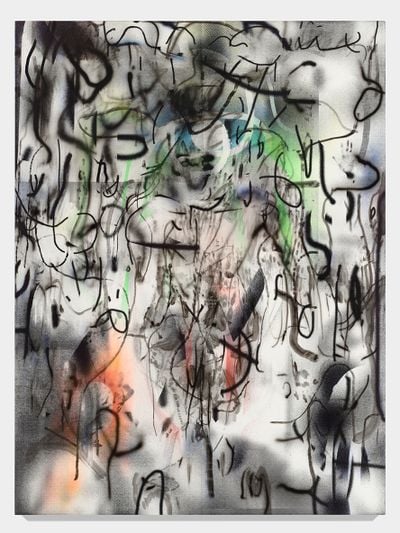

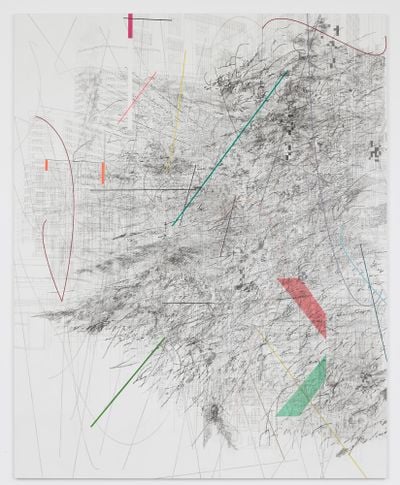

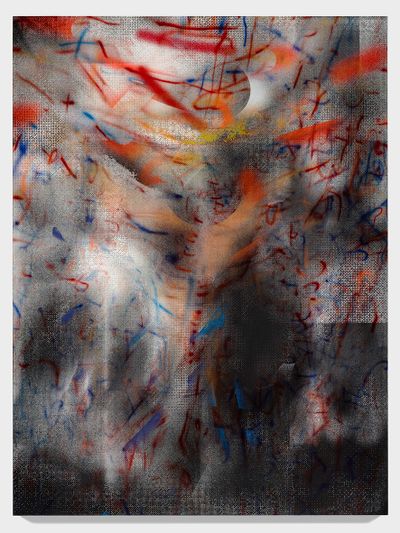

In her recent paintings exhibited at Marian Goodman Gallery in New York, on view through 23 December 2020, the artist has continued to develop what she refers to as insistent gestures and neologisms. They are marks that have progressed over time, becoming larger in size, decisive in stroke, and referential to forms before them. This newly invented language emerges from her desire to further develop the space she creates, where she reimagines the potential of the liminal expanse born in the in-between or transitional place.

Always circling back to biblical references, Mehretu's exhibition is enveloped in its drama. Like the clouds over The Raft of the Medusa (1818–1819) by Théodore Géricault, the exhibition recalls the Book of Revelation and the narrative of the Seven Seals of God that eventually lead to the beginning of the apocalypse.

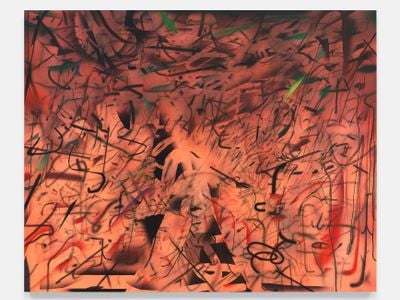

It is in that moment before the apocalypse, and in that impossible frame of theological time, that Mehretu finds the space for another possibility. In these paintings Mehretu works dynamically, starting her process with a news image, which she first digitally alters and blurs. She distils the essence of that image, its spirit and substance, and builds layers of a gradient and saturated palette consumed by blacks and resonating colours, airbrushed and sanded impressions of varying opacity and pointed deconstruction.

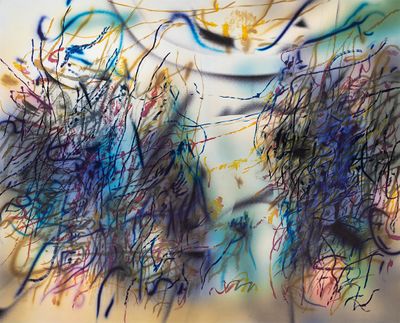

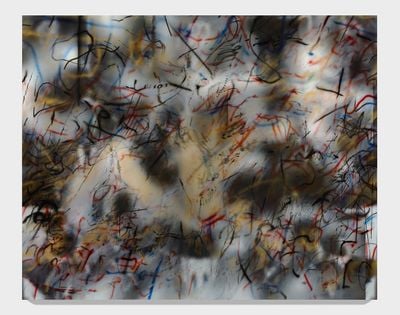

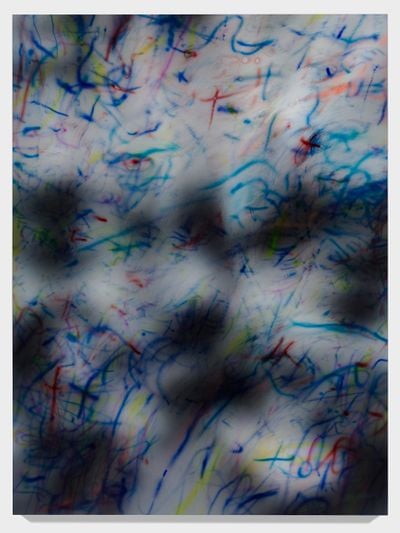

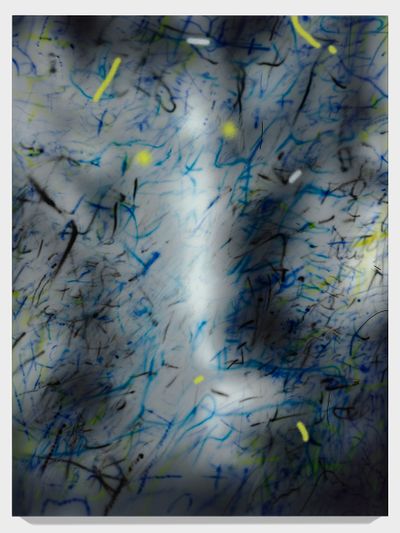

The series of seven paintings, 'about the space of half an hour (R. 8:1)' (2018–2020) depict this hovering between realms. There is a sense of anticipation among streamers of saturated colour, movement, and form, their gestures evoking a post-event in an uncanny space. They are suspended among particles of airbrush, indicating that the dust hasn't settled yet.

Mehretu's paintings collapse space and time, breaking linear progressions of human histories and narratives through repurposing and transformation.

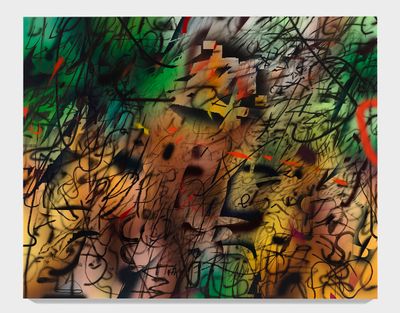

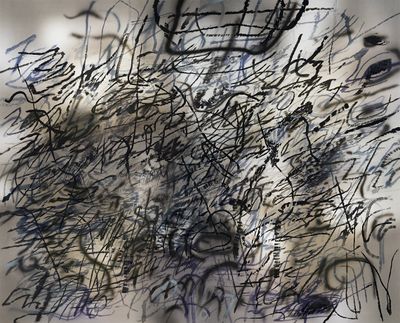

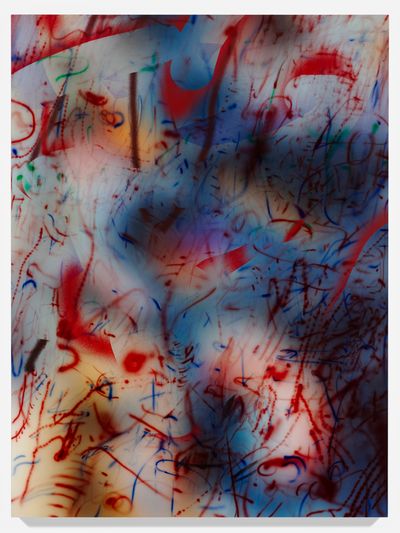

In the series of aquatint photogravures, 'Slouching Towards Bethlehem' (2020), Mehretu references both Joan Didion's collection of essays and W.B Yeats' poem, 'The Second Coming'. Her paintings in this series begin with blurred images of worldwide protests and movements transformed into abstractions of light, shadow, and colour on the large surfaces inhabited by her gestural marks.

The vertigo-induced image both manifests and destabilises the catastrophic logic of those contemporary moments that are alluded to in the works' titles. This is a unique quality in the paintings, which maintain their indeterminacy as delineated in the spaces of near illumination and penumbras manifested by the hovering patterns, computer glitches, painterly streaks, and forms and glimmers of light that push through the shadows. Mehretu's paintings collapse space and time, breaking linear progressions of human histories and narratives through repurposing and transformation. The paintings consequently evoke the possibilities to be discovered within the blur, altering the images into disembodied experience.

'There's an access to this other condition that is insistent,' she explains to me in our conversation. Black lines and shapes hover over masses of shadow and light in another series of seven paintings also in the exhibition. In Loop (B. Lozano, Bolsonaro eve) (2019–2020), the title suggests a realm between contemporary Brazilian political corruption and a dedication to novelist Brenda Lozano whose love story ruminates on marking and erasure.

Here, Mehretu looks to her surroundings. Synthesising her immediate environment and the social and political zeitgeist raging in the United States and the world, she reciprocates with abstraction that resists a single idea, and instead, draws a perspective where a once fortified patriarchal world shows its cracks.

Mehretu's paintings are immersive in this way. Works like Rise (Charlottesville) (2018–2019) allow us to step into these histories of brutal colonialism, orthodox doctrines, and natural exploitation, their demise revealed in a collective punishment of flames devouring parched forests, and revolts and protests fuelled by racial oppression and killings.

The paintings on view demonstrate Mehretu's tremendous creative output during this year of global pandemic. She began some of the painting at the early stages of the pandemic reality in New York, and continued throughout the curfews and lockdowns.

Within this space of anticipation, she constructed a visual language in abstraction, which leaves an afterimage imprinted in the mind's eye, like the fleeting flash-blindness of dark spots that appear after a bright flash of light. This corporeal and time-based experience of Mehretu's paintings feels like an emergence in that instance of anticipation as your vision begins to return, and the swirly lines and dots dissolve. It is the calm before the storm, as the image comes back into focus.

FKYou begin with a photographic image, which is entirely transformed by the time you finish the work: a visual vocabulary that reflects on contemporary experience using the language of abstraction.

How do you think about opacity and abstraction in your practice, working from real-life experiences and events?

JMOpacity and abstraction are at the core of my practice and have been since graduate school. One should never feel the need to translate, or explain who and how one is for anyone else. This has never been asked of white male artists in terms of their identity. Black artists are too often expected to explain who they are in their work, which is based on racist ideas of authenticity.

Radical liberatory practices come from breaking away from the constraints of those ideas of authenticity, language, identity, culture, or any form of determinism. So much of the Black Radical tradition has been based in abstraction, precisely for this reason.

In my work, the language of abstraction has evolved. Painting evolves slowly. But through years of working and mark-making, how I think about space, surface, the marks, and what can happen in a painting has transformed.

I think it really started with the 'Mogamma' paintings (2012)—the scale of them and what takes place in terms of how one optically experiences the paintings. They take time—a different kind of space opens up in them. It is a visceral experience, not just of space, but maybe also in relation to the memory of space and how one experiences that, while the marks become something else in their interaction with the architecture.

When I started to understand this whole time-based physical experience in the paintings, the architectural drawing became redundant to me. It was not necessary as a signifier anymore. At that point, I became interested in the blur.

The blur grew out of projecting a photograph that had an architectural image in it. I was projecting a photograph of a bombed-out street that was out of focus on the projector, and it felt more haunting than tracing the ruins.

Everything that the blurred photo contained felt more palpable. One could not only feel the history of it, but the possible future of that ruin as well—all from this weird blurred photograph. It became more potent, in a way, so I took that as a starting point. I experimented in Photoshop using spray paint and airbrush, trying to create this ephemeral, blurry, hazy space—the blur became the uncertainty of the image.

We live in a super mediated environment, especially considering social media, and every person's reality is differently informed by that. It's like a house of mirrors where we can't locate ourselves, and I don't think anyone really understands our sense of space, time, place, or history within it.

The whole idea of 20th-century progress and ideas of futurity and modernity have been shattered, in a way. All of this is what is informing how I am trying to think about space.

Paul Pfeiffer and Lawrence Chua and I have a collaborative, collective project called Denniston Hill, which has been an artist residency but is also a collaborative creative space to mine and invent forms of liberatory practices and pedagogies.

The whole idea of 20th-century progress and ideas of futurity and modernity have been shattered, in a way. All of this is what is informing how I am trying to think about space.

For the past few years and the foreseeable future, the theme of our interrogation and projects revolve around the idea of exodus and aesthetics of uncertainty. Not the promised land, but rather of the post-emancipatory moment of those 40 years at a complete and utter loss in the desert: the cognitive confusion of that moment and that uncertainty—the haze and blur of the murmurings.

That is the conceptual space that I have also been exploring in my paintings. These blurred photos are of a moment that we collectively experience. You don't need to know which California fire Hineni (E. 3:4) (2018) is—it could be Beirut, Brazil, or Myanmar.

My interest is more in the visceral, collective source of that experience. For me, it becomes this activated, fertile space I can work in and respond to. I think the opacity of abstraction, that space to play with language, is where one can invent other images or possibilities. It's not about delineating or defining some concrete political perspective, or some directive on how to understand things, or even a historical narrative. It's about the collision of all those things—the uncertainty and murmurings of all that.

For a lot of people, this way of working can be problematic, especially so for Black artists or artists of colour, who are expected to explain who they are and to tell the world their perspectives. It goes back to the idea of the right to abstraction—the right to opacity.

FKYou spoke about being in this haze after the chaos. Could you talk about the title of the show at Marian Goodman Gallery, about the space of half an hour?

JMYes. In the Book of Revelations, it's the moment after the four horsemen of the apocalypse are released; after the seventh seal is opened and 'there would be silence in heaven for about the space of half an hour.' It is the moment that's considered the threshold, the calm before the storm, or the space before the apocalypse; before the second coming.

During this whole pandemic, it felt like time was suspended. Many failures of our social systems have been exposed by the pandemic. But, at the same time, especially the first few months, it was this massive pause.

I was working upstate on these paintings, reading Moby-Dick and listening to it when I had insomnia. This story is about foreboding and mayhem, as well as the calm before the storm. We have been completely captured in this suspended, vertiginous, foreboding moment, with our own Captain Ahab catapulting us further into clear disaster. The show also opened the day before the election, so that was another threshold in my conscious.

FKThere's a certain atmosphere of silence. You sense the before and after, then this pause: a fog, particles in the air that haven't settled yet. They are captivating moments in the paintings. There is a disintegration of the image you begin with.

JMYes, I was more interested in that blur and that haze—to find the emergent light and forms within, as well as the absence and emergence of figures and what happens to them within these haunted spaces of imprisonment.

There is a charged DNA in the blur, for me; it affects my interaction with the painting, and it enables me to play with the spectre inside the image.

FKThere is a pleasure in the abstraction, because it negates mapping or outlining things in a linear fashion. Your process is different. Édouard Glissant is quoted in the exhibition, in the urge for opacity. Can we talk about the idea of clamouring for opacity alongside this negation?

JMFred Moten discusses the continual release of the fugitive and the possibility that emerges there—how Black joy can be advanced through negotiating against the constant effort to negate and extinguish that.

There are incredible inventions across American culture that are rooted in the effort to find possibility and joy, in the context of Black creativity and experimentation, despite all efforts against this and through pain.

So even though many of the previous 20th-century concepts of futurity feel shattered and impossible as tropes, there's still a determined persistence on something else that is possible. That is core to my investigation in painting. There is intentionality and intensity in this pleasure and excitement—the fervent effort to make and create—and I think part of that comes from this place.

I'm reading this book, The Mushroom at the End of the World, by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, where she follows the ecology, economy, and history of the matsutake mushroom—a rare delicacy in Japan. Basically, it's this mushroom that thrives in damaged landscapes. She argues that by tracking the mushroom, the people who have travelled the world to pick it—mostly refugees from Southeast Asia—present a case for creative, imaginative ways to reinvent ourselves in the midst of precarity.

To me that is super profound when considering the creative work and creative thinking required of this time. It is our role to mine those possibilities, and to figure out how to continue to exist, insist, and to persist. It's not pessimistic.

I think that the elements of wanting to create, think through mediated images and painting, participate in the history of painting, learn how to make another picture and what that time-based experience is like, and to insist on a visceral, transformative experience that can happen in front of a work, can allow one to participate in those imaginative possibilities.

FKThat's interesting. I was thinking of Fred Moten in relation to how he talks about and brings together improvisation and liberatory practices.

JMYes, I was writing a piece on John Coltrane recently, and I was thinking about how, 50 years ago, coming out of Jim Crow and the denial of any type of humanity, there was still a revered creative force. His work, I think, was to mine and invent another space where he could be free, through concepts of universality and various forms of religion and spirituality.

So how do you do that when you don't have a language for that? You can't use the language of the oppressor in the same way. But it's not just the language of the oppressor—it's the way you understand the world.

I think that's where the neologism comes in—where we invent new words. In music, there's the invention of sound and the constant effort to mine structure and sound. There's the effort in trying to create some kind of texture, space, and experience that goes beyond what can be defined or described or articulated with the language of pain, because experience is visceral and known.

I think the opacity of abstraction, that space to play with language, is where one can invent other images or possibilities.

I'm not trying to speak opaquely, it's just all of this stuff is complicated, contradictory, undefined, and intangible. Is intuition a sense that is mined from the ontological congregation of resistance, an ontological congregation of ancestry; of a collective? How does one have understanding or access to different points of history, of time and of space in their knowing?

Marilynne Robinson said these beautiful words about writing fiction: 'It sounds as if it's some jag of mysticism or something but in fact it's true and I think it's important to me for people to realize that there are much larger, more complex, more consequential entities than most culture allows them to believe . . . when I'm writing fiction the hope is that I will have found my way to something that speaks for itself that is not interpreted but is adequate to interpretation when it comes.'

FKDo you think of abstraction as a tool for this disruption of histories that are presented to us? Considering your earlier works, like 'Mogamma', the 'Being Higher' series (2013), created during the Syrian refugee crisis, or Rise (Charlottesville) (2018–2019), created after the anniversary of the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, for instance.

JMAbsolutely, especially in the architectural drawings—the marks were always trying to be like clogs in the machine. They were trying to devour that system, if you will—work against it, devour it, participate in it, but ultimately, there's this kind of emergent entropy.

I think you see that energy in the paintings in the gallery. There's a kind of fury coming out of what the marks and blurs participate in creating, but there's also this dynamic happening with all of the other elements in colour. I feel like they participate in the construction of a systemic thing, but they also fall apart in that.

It reminds me of Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, who wrote, 'I find myself surrounded by patchiness, that is, a mosaic of open-ended assemblages of entangled ways of life, with each further opening into a mosaic of temporal rhythms and spatial arcs . . . only an appreciation of the current precarity as an earth-wide condition allows us to notice this—the situation of our world.'

I think all of that is a part of the disruption and the kind of breaking of a particular linear narrative. One of the paintings is titled Loop, after Brenda Lozano's book, where the protagonist goes through these cycles that weave from ancient mythology to today, through these repetitive, sometimes creepy patterns. That's the kind of magnitude of time that we connect with that's also broken and disrupted, so I think there's a participation in that, not only in a disruptive way, but also in a generative way.

FKThe surfaces and compositions eliminate a totality in the work. It disrupts how a landscape or an architecture is recognised. The feminist perspective emerges out of these colossal structures—patriarchal histories and events—and messes around with it in overlay and in layering, gesturing to the body, your hand and your brush, personalising it and making it political. The works can't be reduced to a single idea, it's a decolonised and feminist way of making.

JMOf course, part of the intention with the work is to participate in this grand history of painting, which has been dominated by the white male painters for the most part. And institutionally and structurally, whether it's colonialism or patriarchy, or heteronormativity, it all contributes to the history of abstraction.

What I'm trying to do with the making of these pictures is to try to resist, invent, and push against all of that. So, part of it is the scale of the work, and part of it is the desire to work in this language that has been denied to many people, though numerous artists have been working this way for decades. How does one articulate fragmentary breakdown, of a decentred way of looking? A multi-perspectival way of approaching paintings and an openness to their reading? It is all a part of the refusal of autocratic and patriarchal systems.

I think about those things because they are core to not just the way that I make, but also the way that I am—the way I live and participate in the world. This also goes back to what you asked earlier about opacity alongside negation in abstraction.

FKI appreciate that the works take up space as they address spaces that are denied to individuals. I'm thinking about these different elements that deal with the gesturing, but gesturing to the trauma of the event, the architecture, the history. This is not an abstraction of the Western, white, male-centric kind. There's a complexity in your work that liberates itself from constructs.

JMI think part of the effort in trying to find a space for oneself is to constantly be inventing, finding, and mining your own space—insisting that you have that right—as we have to do as marginalised people.

The constant effort of trying to find a space for oneself is to work against and participate in that language: to use that language, to participate in that language, to shift it and morph it, and to create something else out of that, but also to insist on a state of possibility. I keep using that word 'possibility,' without it being too directed.

FKIt seems like an intensive and immersive process, doing this work and mining these images while living in today's reality, and still making art and trying to find other spaces and possibilities.

JMIt is the most potent thing I feel I can do. Morton Subotnick said, in a conversation with Paul Holdengraber, 'The meaning of life, for me, and it never changed, is you find out who you are. Your duty is to find out who you are, what you are, and do the very best you can with that, and share what you do with other people. That's what I've done my whole life.'

I was just recalling a quote from Toni Morrison, 'The function, the very serious function of racism is distraction.' Fundamentally, racism is exhausting. The reality of living through it—that's taxing.

The capability of the persistence on the mark, on it being here, on inventing and finding liberation through it and mining for it, is exhilarating. But you have this history to negotiate and you can't avoid that.

How do you find the break, to use Fred Moten, again, and invent a new dimension in that? Part of the radical imagination is to find and invent those spaces. But also, to go back to Morrison, 'This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.'—[O]