Karla Dickens: ‘the more you know the rules, the more fun it is to break them’

Karla Dickens with her work A Dickensian Country Show (2020). Exhibition view: 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Monster Theatres, Adelaide (29 February–2 August 2020). Courtesy Adelaide Biennial. Photo: Saul Steed.

Karla Dickens with her work A Dickensian Country Show (2020). Exhibition view: 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Monster Theatres, Adelaide (29 February–2 August 2020). Courtesy Adelaide Biennial. Photo: Saul Steed.

Karla Dickens is an artist with Wiradjuri heritage, who combines fine art drawing and painting with rustic, abandoned materials imbued with history and contextual meaning, layered into mixed-media installations and sculptural collages on boards.

In 2019, Dickens was among six contemporary women artists from New South Wales commissioned to produce work as part of the free public exhibition, Dora Ohlfsen and the façade commission (12 October 2019–8 March 2020), which responds to Australian sculptor Ohlfsen's cancelled commission for the façade of the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW). To see or not to see (2019), Dickens' proposal, will be re-presented on the gallery's façade for AGNSW's 150th anniversary in 2021. It features the artist's head with a white hood covering her face in reference to the spit hoods put over the heads of Aboriginal children in the Northern Territory Don Dale Youth Detention Centre, and Mona Lisa's image printed on the exterior.

Dickens thinks through questions on place and politics in Australia and invites audiences to do the same. Recently, her genre-defying installations appeared in Brook Andrew's 22nd Biennale of Sydney, NIRIN (14 March–8 June 2020), and the 2020 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art, Monster Theatres (29 February–2 August 2020): works that grew out of grants that Dickens received in 2018 from the Copyright Agency Fellowship for a Visual Artist and the 2018/19 Creative Koori – Arts & Cultural Projects fund, which allowed her to research Con Colleano, a world-famous Aboriginal tightrope walker.

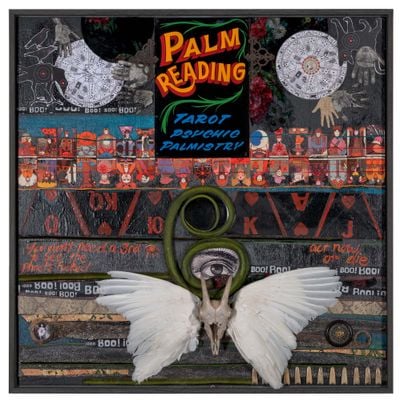

Both installations track the darker side of Australia's touring sideshows, boxing tents, country shows, and circuses. A Dickensian Country Show (2020), shown in Monster Theatres, comprised an installation of discarded objects from funfairs alongside 3D works on boards on which circus paraphernalia mirrored the installation's aesthetics. A Dickensian Circus (2020), as part of NIRIN, filled the foyer of the Art Gallery of New South Wales with found objects sourced from Dickens' local tip: a mix of found rusty buckets hanging from the ceiling, cages on plinths imprisoning feathered heads, and old toys perched atop of old oil bins, while looming bodies printed on hanging banners kept guard over the installation. Dickens continues to develop these works, and later in the year (pending Covid-19) they will tour regional Australia by following the steps of the first country shows and circuses.

Throughout her work, Dickens extends themes of recuperation from the community to the environment. Last year, the artist collaborated with the historian, scientist, and novelist Bruce Pascoe for My Mother's Keeper (2019), which was commissioned by Kandos School of Cultural Adaptation for Cementa13, in a national project titled, 'An artist, a farmer & a scientist walk into a bar...' Set in Bingara, a small town in New South Wales near Moree, Dickens collaboratively produced a video that features Pascoe and schoolchildren from the community wearing capes the artist made. Each cape is stitched with words including 'Respect', 'Care', and 'Culture', and for Pascoe, 'Mother Earth Country', as they navigate the arid environment of the rural town. Initially set to exhibit at Linden New Art this year, due to Covid-19 the work is currently available to view digitally.

In this conversation, which took place in March, Dickens talks about the effect moving to a regional town had on her practice, developing the history and context of A Dickensian Circus and A Dickensian Country Show, the relatability between Australia's landscape and the treatment of First Nations peoples, and being the first woman to present work on the façade of the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

EKWWith the Adelaide Biennial and Sydney Biennale opening within a few weeks of one another, you must have had a really busy few months!

KDYes, the 2020 Adelaide Biennial was a really big hang, and a huge social event. Then I went straight to Sydney to hang work for NIRIN at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. I know what it's like to keep busy, yet I'm not familiar with large openings and crowds back to back. In between shows, I'm just working in my studio. I'm a single mum, so I work, and then my daughter gets home. I live a really insular life. When you go out to the big cities for openings, it's a different world.

EKWYou live in Lismore, in the regional Northern Rivers area of New South Wales. I imagine it's pretty quiet there. Does the pace have an effect on your practice?

KDWell, I got a shock yesterday, because I find most of my objects at the recycled shop at the tip, but it's closed at the moment due to Covid-19. The objects I collect and that I'm attracted to are a lot easier to source regionally than in a city, and I love that. Lismore is close to the bush, mountains, and the sea. It's affordable. I have space to create with a couple of studios, a large garden, and room for friends and family if they need it. Affordability was a large drawcard for moving out of Sydney—the lack of financial stress gives me a different kind of space to create.

EKWDo you think moving out of cities is something that more artists should do?

KDFor this artist, it was a no brainer. The Northern Rivers region of New South Wales has the largest population of artists outside any capital city. It's super conducive to creativity and alternative lifestyles. Since the seventies it's been an area that's been attractive to liberal thinkers; there's a huge gay community that is largely accepted. People are very environmentally aware and embrace the strong Indigenous community and culture. I could sell the area all day to any artist that would listen, just as long as the tip shop doesn't get taken over by sculptors [laughs].

EKWHow has moving to Lismore affected the work you're making?

KDAs a single mother who's been making art for a long time, art hasn't always been able to feed me. I need a sense of security; I know I need a roof over my head to really be able to let go with my art. The price of living means I don't have fears and concerns about paying bills and also means that more money goes towards my art.

EKWYou've been a practising artist for over 20 years, but it feels like there has been a surge of interest in your work over the last couple of years. Do you think that's because you are now able to put your full attention into it?

KDI've always made art, and I've always been passionate about it. My daughter's 14 now—when she was a few years old I came to realise I had to take art more seriously and push for commissions and funding and possibly a gallery to represent me. I was forced to do things that I'd never done before if art was going to be my main focus. Being a mother and having to feed my daughter was the catalyst for me, pushing my career forward. As a hard-working artist, I have seen my work developing for the better and becoming stronger as time goes by. I can only hope the work is worthy of the interest.

The making of art is my oxygen, similar to the instructions given to you on an airplane: 'Breathe through the mask first before helping others.'

EKWI often find myself interviewing mothers; it's interesting to hear how motherhood influences the practice.

KDAs a single mum with a young child who needs routine and early nights, I found myself taking advantage of the new structure in my life and really needed to make art to keep sane. Mothering my daughter taught me some serious lessons in responsibility—making art was the self-responsible action I needed to take for myself. The making of art is my oxygen, similar to the instructions given to you on an airplane: 'Breathe through the mask first before helping others. If you run out of oxygen, you can't help anyone else.' I doubt I'd be much of a mother without it.

At art school, I was always told: 'You'll never be successful because you're a woman and you'll probably have a kid.' I think most of the women I know have proved that to be untrue. Being told I can't do something is usually the perfect incentive.

EKWThinking back to art school, was your education a catalyst in your career?

KDDefinitely. The beauty with the National Art School in Sydney is that it wasn't academic-focused. It was very much about your practice, and so I really learnt how to just keep showing up at the studio. I learnt about the process of making art—the fears, the mind games, and the drive needed to push through regardless. Having artists with professional practices as teachers was priceless. It was definitely a turning point for me. I was 24 when I started, and it was the first time I'd actually committed to something. Life made sense being surrounded by creatives.

EKWWhen you look back now, do you see your development in a new light? Have certain things been revealed to you over time?

KDOne hundred percent. I was 24. I had been running amok as an addict before re-channelling my energy into art. So much has changed in my life inside and out; I have no doubt it will continue to challenge me and reveal new ways of seeing and learning. I always hope that I keep seeing things in a new light. The current world crisis appears to be the new learning curve—the new challenge—as we rethink, revalue, and process.

EKWYou started with painting and then switched to a more installation-based practice, right? Can you describe that transition?

KDI enjoy conversations with different people, just as I enjoy conversations with different materials. To be blunt, I got bored, and I find that different stories are told more effectively with different mediums. My training in painting and drawing is still a strong and valuable foundation. As much as I resisted formal training, I strongly believe having that foundation has really helped with any kind of abstraction, reconstruction, and deconstruction that I explore.

I've always loved the idea that the more you know the rules, the more fun it is to break them. I really value those skills now, even though I didn't at the time. I struggled to go to drawing and to do all those basic exercises. I can see and sense how valuable those lessons were in the studio today, no matter what medium I choose to work with. When I was installing at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, I realised I was thinking of that space in terms of composition, which came directly from those days at art school.

EKWI read that you began collecting things for your artworks early on as well.

KDBasically, I couldn't afford the paint, so collage came from necessity. This led me to realise how contained and tight my painting can be. Working with collage and 3D objects, I found more freedom and the work became looser. Recently, I produced a series of sculptures on boards for the Adelaide Biennial. I'm really pleased with that new progression—I'm keen to do more of that.

EKWYou also incorporate a lot of written word in your artworks. When did you start doing this?

KDWhen I started working on the profoundly emotional works—disturbing pieces about rape and abuse on women—I began to write poetry because I didn't want to go to a gallery and do interviews with people asking me about the work. It was hard to speak about. To work around this, I started writing poetry to fill the gap. I've really enjoyed that part of the work; it's been a great help in consolidating what the art is about. If I'm working fast—gluing, drying—I'm not always conscious about the concepts of the work. I run with what comes, then I sit back once it's finished to consider the work. The writing is a part of that process. Being dyslexic, computers have helped with my writing—spell-check is a godsend.

As much as I resisted formal training, I strongly believe having that foundation has really helped with any kind of abstraction, reconstruction, and deconstruction that I explore.

EKWIn an article about your practice published last year in The New York Times, you are quoted saying that lately, in your work, 'There's a feeling of coming out of that old, deep age of darkness and pain [...] A feeling of coming out into the light.' How do you feel about that now? Do you feel like your works have taken that new progression?

KD[Laughs] No. They're probably not as personal, but I've surrendered to the fact that there's a darkness in me and my work, especially if you're looking at the treatment of First Nations peoples in this country. Historically and socially, joy isn't a part of an honest account. I was seriously in search of lighter, more joyful stories and experiences when I made the decision to focus on circus life in Australia. It was early in my research that I realised I was being too optimistic, and of course, the lives of First Nations peoples had pain and injustices, whether in a circus or prison cell.

I think my work looks quite dark with the materials I choose—a lot of everyday objects that are connected with working-class people. The working-class aesthetic is quite dirty and grimy—it's not shiny, so even if the work has a positive, upbeat story behind it, it's still going to look quite dark. I think this comes from being so influenced by my grandparents and a real working-class mentality. People come home from a day's work, and they're covered in dirt; they're tired and sore, and I quite often feel like that when I come out of the studio.

EKWThat's interesting to think about in relation to the juxtaposition of A Dickensian Circus against the classical architecture of AGNSW for the 22nd Biennale of Sydney.

KDWhen the space was first offered to me, I started making work to counter the panic. Once I caught my breath, I decided a trip to Sydney was needed to have another look at the space. The panic was a reasonable response—the vestibule was much bigger and flashier than I ever remembered. After the visit, I realised the power of having rusty, working-class objects in that space, telling an Indigenous story. The size of the marble columns had a strong impact on me, which led to the decision to do a photoshoot with role-playing circus performers, Cindy and Jeff.

EKWCould you tell me a bit more about Cindy and Jeff?

KDGiven the sculptures I had been working on were quite intimate, I really felt the space was demanding images of Aboriginal faces, almost like guardians. Cindy became Ms Ready and Jeff, Mr Willing. Ms Ready emphatically reclaims this sacred space with her legs mirroring the strength of its marble columns, an exotic Koori knockout with serious attitude, taking complete ownership of the Australian flag, wearing a sequin mini dress representing the stripers and leg girls that often toured with the boxing troupes. Mr Ready firmly stands his ground—not just as a tent boxer, but as an Aboriginal man whose resilience demands respect. Both faces speak about the resilience, strength, and power to survive.

EKWDoes this work flow into Dickensian Country Show at the 2020 Adelaide Biennial?

KDYes, it does, I worked on both exhibitions at the same time; I'd do some sculptural works, and then I'd do some work for the wall. Thankfully, after receiving funding, I could afford to search and purchase objects to create the amount of work for both spaces. Both exhibitions explore the same stories, which I'm yet to finish. I'll have another show up at the end of the year, travelling to some rural galleries, which I'm really excited about.

EKWCould it be mirroring those original touring circuses throughout the country as well?

KDThat's right. There's an opportunity for people to come forward and share stories about their family stories from boxing and circuses and carnivals. It was easy to find stories about the boxers, but to find stories about the women was incredibly hard. People didn't have the freedom to leave missions or communities without having written authority, so often they hid their Aboriginal identity.

I've surrendered to the fact that there's a darkness in me and my work, especially if you're looking at the treatment of First Nations peoples in this country.

EKWEarlier, you mentioned the incarceration rates for Indigenous peoples, and I wondered whether these artworks speak to any other narratives that continue today?

KDDefinitely. Even the large sculptural work at AGNSW that hangs from the ceiling, There's a Hole in my Bucket (2020), which comes from the old nursery rhyme, seems very apt and relevant for Indigenous peoples then and now. We're going forward with holes in our bucket, whether that's trauma, racism, or political policies. Not much has changed. Children are still being removed.

EKWIn terms of First Nations responses, I was interested to hear your take on NIRIN and working with Brook Andrew. Do you feel that there is a change happening in the art industry?

KDThere was definitely a change in the Biennale of Sydney, 200 percent. And the way Brook works, he really trusts you as an artist. It's very much artist-led, and he is incredibly respectful of you as a woman. I came away from that Biennale so full of hope and so inspired by the work that was presented; his curatorial skills are mind-boggling. I've come home so rich, hearing and seeing all the stories that were presented.

EKWIt's great to hear your perspective and the support that you got from Brook. It makes me think about the industry on a larger scale and whether that humanist approach is lacking in a lot of other places?

KDTotally. As an Aboriginal, a person with disabilities, a parent, and as a middle-aged woman, so often you don't get heard when you speak; you're just invisible. When the fires were up here, Brook was contacting me and other members of the Biennale to ask us how we were. We were being treated as humans in that process, and not just as producers of work that's going to go into a space and entertain people.

I was seriously in search of lighter, more joyful stories and experiences when I made the decision to focus on circus life in Australia.

A lot of the work I create is based on trauma, and that can involve hours in the studio revisiting personal pain, with my heart wrapped around my throat. There are those in the art world who have no understanding of the depths that artists visit to create work, on top of everyday calls of duty from family and the community. More and more audiences are seeking out stories of truth. They visit galleries to seek that connection out, but to have that you need humans to make it. I still feel like there's a real distance between the artist involved in the work. Artists work in isolation a lot the time; we go to these really deep places, and then you open the work up to the public and have to sort of switch it on. Interesting, right?

EKWYes, it is. There're so many different levels, and if you're one of those people whose mind goes into those places, it can really get you thinking about the deeper connection between artists and their works.

KDMy work is about layers—of collage, materials, and history. I love layers. That's what I sit and think about when I'm having my coffee in the morning: dynamics and dialogue between people, their different histories, different experiences, and how they choose to express themselves.

EKWI also wanted to talk about the work you created with historian, scientist, and novelist Bruce Pascoe, My Mother's Keeper (2019), showing at Linden New Art until 30 August 2020.

KDYes, that was a really interesting process with a project for Kandos School of Cultural Adaptation in Cementa13. The project, 'An artist, a farmer & a scientist walk into a bar...' saw a collaboration between Bruce and I. My Mother's Keeper was made in Bingara, a small NSW town on the way out to Moree. It was a long process, starting with visits to meet the locals, and becoming more familiar with the landscape. While we were out there last year, it was so dry. The birds were walking around with their beaks open, from lack of water. It was a challenging slap across the face to experience such intense climate change effects on the landscape, farmers, and wildlife.

When we went out to shoot the footage, there were horrendous dust storms. We were surrounded by bush fires; my nose was bleeding from the dust. The heat was overwhelming, uncomfortable, and very confronting. There were tears, fears, and the realisation of just how traumatised the landscape really is. Traumatised First Nations people living on traumatised country. It was a really hard work to make. I get emotional just thinking about being out there. It was really challenging.

EKWYou know, I always feel, especially in Australia, that there is such disconnect between the cities and the rural towns. It's just so crazy to think that people are living like that here, and then people elsewhere are just ignoring the truth. I can't imagine how difficult that must have been turning that into an artwork. What was that like as a process for you?

KDIt was difficult, and incredibly rewarding to step outside of my usual comfort zone of creating in isolation to working with others. I first started with making the capes for the children with the words 'Respect', 'Care', and 'Culture', on the back. Then I made a cape for Bruce with the words, 'Mother Earth Country'. Bruce doesn't talk in the film, so it's basically him walking around as Mother Earth, looking and listening to the destruction. I was happy to have a man wearing the coat with 'Mother' on it. I would like to see a lot of men, especially those in government, wear it for a while. He walked through the landscape, feeling and looking through the eyes of Mother Earth, connecting with the kids. The only positive outcomes from the virus will most definitely be forwarded on the planet, as we live smaller lives.

There are those in the art world who have no understanding of the depths that artists visit to create work, on top of everyday calls of duty from family and the community.

EKWI've been having that conversation as well. I've just had this feeling for a while that, especially after the fires, the earth has had enough. I think it just puts everybody on the same level in some way. We're all susceptible no matter where we come from.

KDIt doesn't matter how much money you've got, or how many rolls of toilet paper! I'm really excited to be in lockdown with my daughter, returning to the basics. We've got a great garden, that will only be producing more after this experience. My grandparents lived a simple life that was very self-sufficient, governed by little consumerism. In that film with Bruce, we did some filming at the local tip, where there are white goods piled up like a mountain, hills of tyres and shitty objects that were never made to last. We are eating ourselves.

While in Sydney, I heard a talk with Arthur Jafa, and he said how arrogant humans are to think that we are more important than this virus. The planet is fine; it's us who have the issue. It's all about us and the choices we make. That was another great thing, to see so much environmental focus in the Biennale of Sydney. I don't wrap my work with bubble wrap, I go and get old, second-hand cardboard. It's all possible.

EKWCongratulations on your work To see or not to see, presented as part of the exhibition, Dora Ohlfsen and the facade commission, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Interestingly, this work is very close to the one showing in the Biennale of Sydney, moments away from the foyer.

KDHow blessed am I? It's a really momentous work—the first woman's work to be shown on the outside of AGNSW, and most definitely the first Indigenous work. I was excited to learn about Dora, her story, her talent, and her struggles, along with the other talented and successful women who created proposals for the exhibition. This was a truly significant opportunity as a woman. The voices of women need to be heard in the arts. When I think of Dora, I have so much empathy and respect for any artist who continually works, whether they are successful or whether the light gets shone on them.

EKWIt's crazy that you will be the first woman to show work on the outside of the gallery.

KDI know, I think there are a few more spots up there. I think they should just keep going!

EKWDo you have any other exhibitions coming up?

KDI'll be finishing the Dickensian Country Show project and then the 150th anniversary of AGNSW in 2021, where To see or not to see will be shown. I'm keen to bunker down in my studio and build a few things. It will be interesting to see artists' responses to the position that the world is now. Who knows what's to come?—[O]