Kim Yong-Ik

Kim Yong-Ik. Courtesy Kukje Gallery. Photo: Keith Park.

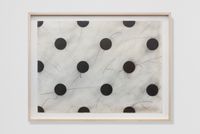

Kim Yong-Ik. Courtesy Kukje Gallery. Photo: Keith Park.

Kim Yong-Ik is the understated rebel of the Korean art world. Over his 40-year career as an artist, writer, and curator, Kim has resisted categorical affiliation with dominant art movements in Korea, from the monochromatic and minimalist paintings associated with Dansaekhwa, to the sociopolitically concerned Minjung or 'people's art' in the 1980s.

Declining an offer to align with the latter group in 1985, Kim committed himself to challenging the principles of modernism and the avantgarde by embracing an 'anti-art' aesthetic and concealing his political gestures in subtlety.

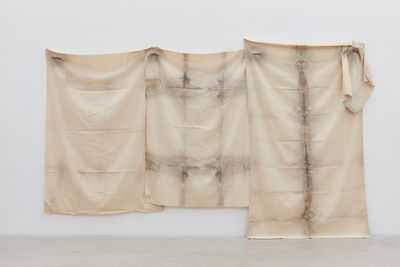

Born in 1947 in Seoul, he conceived the formative 'Plane Object' series (1974–1981) while still an undergraduate at Hongik University, where he graduated with a BFA and MFA in painting in 1980. The series comprises wrinkled, washy, and airbrushed unstretched canvases, hung directly on the wall and lightly painted to give the illusion of depth and folds. These illusory works quickly attracted attention in the mainstream art world; but Kim, uncomfortable with the trappings that came along with recognition, stopped working on the project in 1981.

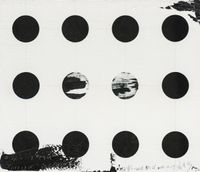

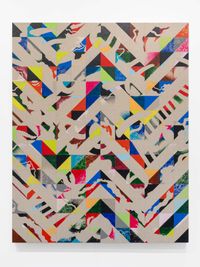

By the early 1990s, he had begun painting polka dots—repeated and perfectly aligned in columns and rows—on mostly plain backgrounds. In defiance of precision, Kim deliberately blemished the canvases by smearing them with dirt, vegetable juices, and other substances, even circling and annotating the imperfections with pencil to draw the viewer's attention to the 'mistakes'. This intentional ruination has been a consistent theme throughout his practice; Kim is none too precious about his work. He is known for intentionally contaminating or soiling his canvases and sometimes leaving them outside to amass mould, all to the ends of what he calls 'eco-anarchism', or the embracing of decay and cheap materials to minimise waste.

Over the years, Kim often addressed, repeated, and modified his own earlier projects, asserting that art history has reached a point in which nothing new can be produced. In such a state, he says, artists are mere editors of theirs and others' work.

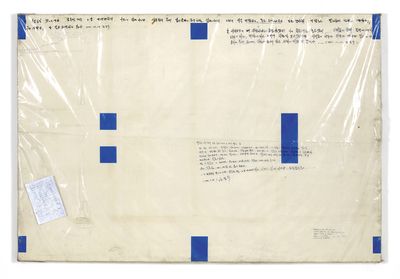

On multiple occasions, Kim has left his works enclosed in their packaging with only their labels left to indicate their titles, materials, and dimensions. The first example of this was in 1981 when the artist was invited to participate in the 1st Young Artists Exhibition held at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Seoul; whereby Kim left his works enclosed in opposition towards the increasingly repressive military dictatorship in South Korea at the time. This act is closely linked to his entombing of old works in more recent years, in which the artist encloses earlier works in 'coffins' and re-exhibits them.

I'm constantly reappropriating my old works, and sometimes even the work of other artists.

For his 2016 solo exhibition at Kukje Gallery in Seoul (22 November–30 December 2016), Kim transferred images from past sketches and prints to canvases and deemed them new pieces. In the same year, he staged his retrospective Closer... Come Closer... at Ilmin Museum of Art in Seoul that year (1 September–6 November 2016). In 2018, Kim presented approximately 40 works—including crated works, polka dot paintings, and conceptual drawings—for his solo exhibition at Kukje Gallery, Endless Drawing (20 March–22 April 2018).

At 71, Kim is affable, good-humoured, and generous in conversation. I spoke with the artist at Art Basel in Hong Kong in 2018, where Kukje Gallery presented a solo booth of the artist's work as part of the fair's Kabinett sector.

EAWhat was your experience of art school at Hongik University in the 1970s?

KYIIn the 1960s and 70s in Korea,the avantgarde and modernist art scene was in its nascent stages. Even the Dansaekhwa painters that we know now were very much under the radar, and there weren't that many magazines or publications on Western art at the time.

Even if there were, not many people could read them. But a lot of the Dansaekhwa monochrome painters knew how to speak and read Japanese. So, in a way, the modernist language came through Japan. My Japanese and English are very limited, so my only sources were short translated excerpts about the Western avantgarde that I was very excited to read. Among the scene, Hongik, a journal published by the students of Hongik University, was relatively progressive.

To me, an artwork is not a finished or perfect thing. It can always change.

EAHow did your 'Plane Object' series begin in the 1970s?

KYIAt the time, I was reading about the Japanese Mono-ha movement and read one of the artistic statements, which essentially said, 'leave things as they are'. It really struck me. All the Western art history that I had learned fell apart after reading this. What I had previously learned was that art was either abstract or figurative—it was about representation and the involvement of the artist, basically. But Mono-ha taught me that things could be just as they are.

You don't need the artist's intervention. That really struck me. I think the concept itself was not entirely foreign to me, because I was exposed to the philosophy of Lao Tzu early on, which was all about leaving nature as it is. Now I realise that this philosophy was part of both my consciousness and Korean culture for thousands of years, but I didn't realise it until I read the Mono-ha statement. I feel that the philosophy was really destroyed during modernisation and the war in Korea. It's constantly collapsing, even still.

Going back to the 'Plane Object' series, I thought, why not just leave the canvases as they are, without adding any elements to them? Mono-ha artists exhibited their objects without altering them. I do a little bit of airbrushing to create visual tricks. The works show depicted versus literal lines in a very intricate way. That idea is constantly reflected in my practice to this day. It could also stand for how I'm constantly trying to connect my actual life as an artist with my art.

EAYour use of disposable, cheap, ordirtied materials is described as 'eco-anarchist', a philosophy you took towhile taking part in the Sandarbh International Artist Residency in India in 2009. What do you mean by that term?

KYIIt arises from the fine line between art and everyday reality. I'm constantly thinking: 'I'm an artist, do I want to be an artist, this is an artwork but this doesn't want to be an artwork.' How do I rectify that? The term is a combination of different philosophical ideas and is not a word that I've created myself, but I adopted the term to explain my idea of how an artwork should embrace damage and be open to change. The artist should be allowed to destroy the work if he wants toembrace dirt and time. I'm very keen on humble objects and I wish to leave my works open.

EAYou've said that you're addicted to the comforts of capitalist life and have lost all basis to argue for eco-anarchism. Therefore, your works are a form of self-consolation or self-deception. Do you feel consoled by your own work?

KYIThere is a sense of relief, but not an overwhelming one. It's very timid.

EAIf the contemporary world has exhausted its ability to generate new art, and now artists can only reappropriate and rearrange existing artworks, do you consider yourself an editor?

KYII'm constantly reappropriating my old works, and sometimes even the work of other artists.

EAWhat appeals to you about polka dots?

KYIIn the 1980s, I moved from the 'Plane Object' series to more abstract and geometric languages. I made some wooden panel pieces that mimicked the drawings. While I was working on that, I tried to damage these pieces by cutting circular holes in them. A circle is very easy to cut.

EAI would have thought it's very difficult.

KYII use a compass, which is the easiest device to use to create a perfect form. If you want to draw an accurate rectangle, it's very difficult to be precise. I started these works on thick panels, and then I moved to more two-dimensional surfaces in the 1990s and started painting the dots on the surface instead of cutting them out.

One day, while I was doing this, I realised they can be in a perfect grid, and the grid itself is a language of modernism. I never presented the polka dots as they were, in a well-aligned manner. I always created a little crack or blemish. That's also part of my personality. I was never outspokenly resistant to modernism, but I always like to create little puns here and there.

I titled those paintings from the 1990s 'Closer... Come Closer...'. From a distance, they look like modernist paintings. But if you move closer, you can see little marks, cracks and even where I sometimes stick my hair on the surface.

EAWhat do you think of when you see your 'imperfect' works in a white cube setting?

KYIOf course, the works do end up in galleries and collections, which contrast the imperfections I embrace. But I'm trying to destroy modernism and create a crack from the inside, like a Trojan horse.

EAYour work has been described as having a punk sensibility. What do you think about that?

KYITo me, punk connotes a very energetic and unrestrained force, but I think that I am more subtle. I want to delay a fixed interpretation of my work.

EAPunk can also describe one who is rebellious and has a penchant for breaking the rules.

KYIThere is a true rebel inside me, but when I perform that into an action, I'm not a very energetic and aggressive type. I'm a moderate.

EAThat's interesting; it reminds me of how, on the surface of one painting in the 'Closer... Come Closer...' series, you wrote: 'I am never an aggressive type, as all avantgarde has been'.

One definition of drawing that you have put forward is that it is a continuous work-in-progress. What do you mean by that?

KYIThe idea of a drawing exhibition is not medium-specific. I don't want to define the drawing by its medium in a traditional sense, so I gave my own definition. This idea of modernism that I'm trying to overcome is not just in terms of style, it's also about the modernist idea of life.

For example, I think that modernism is about function and efficiency in society and I want to go against that. Art students and artists are obsessed with trying to create a finished product. To me, an artwork is not a finished or perfect thing. It can always change. Our society and art should embrace things that can change. I want the art students who visit my shows to feel a sense of liberation.—[O]