Curator Kimberli Gant on the Legacy of Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club

Kimberli Gant. Courtesy Kimberli Gant.

Kimberli Gant. Courtesy Kimberli Gant.

In the 1960s, the Harlem painter visited Nigeria, where he connected with the Mbari Club and its magazine Black Orpheus. What he discovered, Gant says, is artists who were asking, 'Who are we now that we still recognise and connect with the contemporary art zeitgeist but at the same time, come from so many art practices, legacies, and traditions?'

The African independence movements commenced during the postwar era were partly a struggle to reimagine the continent beyond disastrous and exploitative impacts of colonialism. Amid violent geopolitical thrusts toward liberation, questions around identity, culture, and nationality became as important as those concerned with land and borders.

Within this context, artistic expression became a focal point for revolutionary ideas and debates—ones that echoed out from the continent, reaching the United States and beyond.

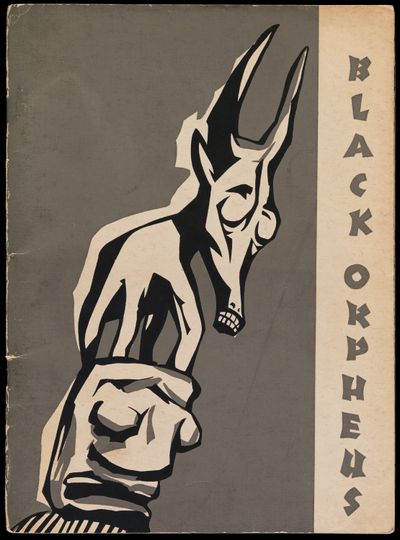

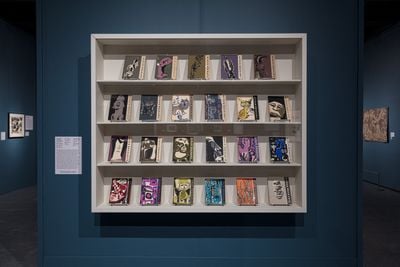

At the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA), Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club (10 February–7 May 2023) presents works that exemplify the zeitgeist of this period.

The exhibition is co-curated by Kimberli Gant, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, and Ndubuisi Ezeluomba, NOMA's former curator of African art who is now at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Placing the late Harlem painter Jacob Lawrence in conversation with his contemporaries in West Africa through their research into the Nigerian Mbari Artists and Writers Club and its influential arts and culture magazine, Black Orpheus (1957–1967), Gant and Ezeluomba show how artists, many of whom have not received due recognition, came together to express the energy, aspirations, and aesthetics of the time.

Born in New Jersey in 1917, Lawrence spent much of his life in Harlem, where the cultural milieu inspired the subject of his paintings. His most well-known work is 'The Migration Series' (1940–1941), a series of 60 tempera paintings depicting the experiences of African Americans during the First Great Migration (1910–1940) who, like Lawrence's family, migrated from the rural South in search of better lives in the Midwest and Northeast.

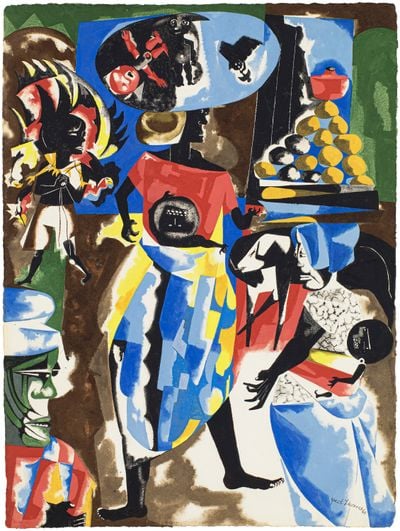

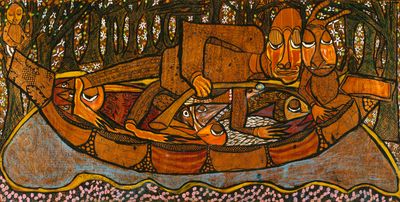

Lawrence travelled to Nigeria in the 1960s where he met with artists of the Mbari Club and started work on his lesser-known 'Nigeria' series (1964–1965), which captures the energy, sights, and sounds experienced on his journey. Trips to Africa placed Lawrence in the company of others attracted to the liberation movements underway in the continent, and fuelled his interest in rendering Black experiences.

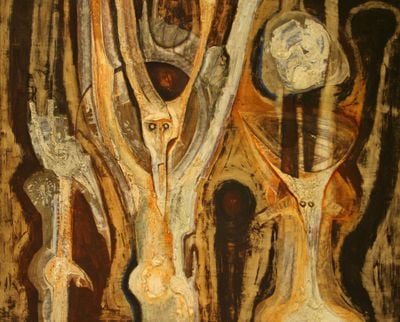

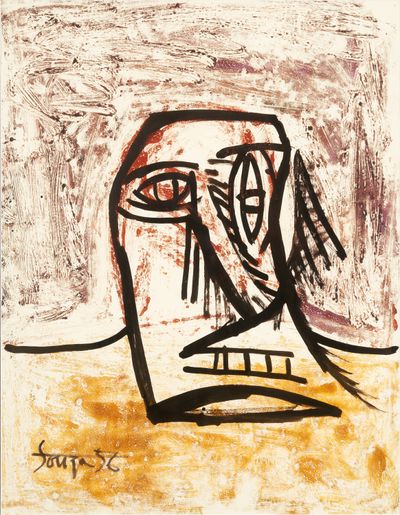

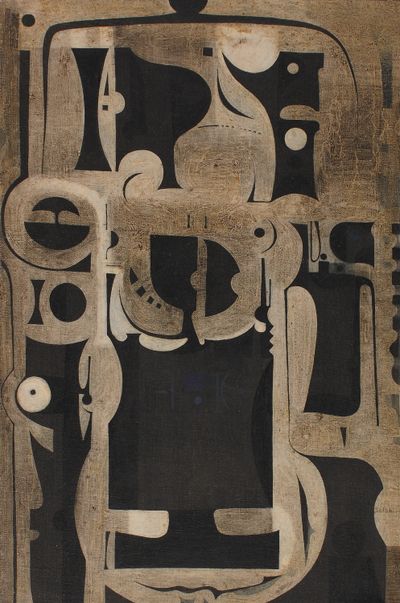

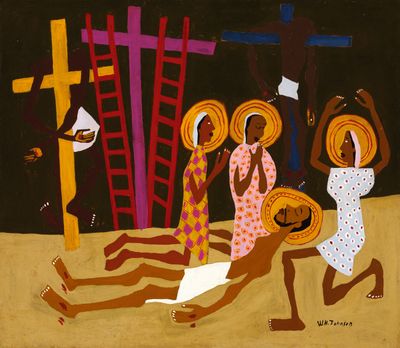

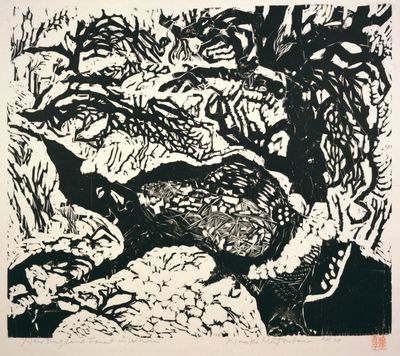

Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club features over 125 objects including the 'Nigeria' paintings, archival material, and works by artists featured in Black Orpheus magazine such as William H. Johnson, Ibrahim El-Salahi, Uche Okeke, Malangatana Ngwenya, Jacob Afolabi, Colette Oluwabamise Omogbai, Francis Newton Souza, and Wilson Tibério.

The show is a rare opportunity to explore how Lawrence, the Mbari Club, and other similarly inspired artists created art, spaces, and dialogue informed by a transnational movement for freedom.

NPTell me about the genesis of Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club.

KGIt came about through the collections research I was doing while a fellow at the Newark Museum. I looked at Jacob Lawrence's catalogue raisonné and learned of his time in Nigeria.

Coincidentally, I was also doing my dissertation on imagery of Nigeria. I was looking at African modernism in cities and read about Lawrence's time in Nigeria in Chika Okeke-Agulu's book, Postcolonial Modernism: Art and Decolonization in Twentieth-Century Nigeria (2015). So, there was this synergy happening. It was this idea that stuck in my mind.

I'd never heard about Lawrence's time there with his wife, Gwendolyn Knight. Through further individual research I found out about Lawrence's former gallerist, Terry Dintenfass, who has passed. But her son Andrew Dintenfass and his wife Ann have been working with the estate. They had a piece from the 'Nigeria' series which was also in Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965 (2016), an exhibition Okwui Enwezor co-curated at Haus der Kunst, Munich, before he passed.

I then started working with DC Moore Gallery to try and find where the other works in the series were. But I realised that I couldn't put together the type of show I really wanted. I had the genesis of an idea but needed more time to flesh it out.

I joined the Chrysler Museum in 2017 and was able to spend more time on the project. I had known Endy (Ndubuisi Ezeluomba), who at the time was a fellow at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

I wanted someone who I could partner with on the show. I was much more of a contemporary specialist—I didn't really have the historical context, which Endy very much has. There was a good synergy, in terms of what we each could bring, which complemented each other.

NPThe Mbari Club was a significant space in West African intellectual history and is featured prominently in the show. The club hosted and supported the early careers of people like Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe, and many other writers, artists, and musicians. How does it connect with Lawrence?

KGI had known of Lawrence and his connection to the Mbari Club—I knew that the club and the journal, Black Orpheus, were my linchpins—a kind of thread throughout the exhibition. That's really what connected Lawrence and the Mbari Club together.

Then there were artists that weren't a part of either but were still having their work presented and promoted globally. From there, it was trying to find out where the Lawrence works were, where the Mbari Club works were, and where the journals were. There was a lot of effort in pulling these pieces together.

NPTell me about that process—I imagine it was challenging logistically.

KGWe got lucky because of Lawrence and his reputation. He was prolific and there is a gallery that represents his estate. We benefitted from the fact that he had a catalogue raisonné—we knew what the works looked like, that was a great starting point.

We were then able to start tracking. It involved a lot of cold emailing and letter writing, a lot of negotiation. It's really a combination of looking at the research and asking about the works, trying to locate them.

NPThese works have not been shown for a long time, over 50 years. Why has it taken so long to see them presented?

KGUnlike 'The Migration Series', which is split between two major museums, Lawrence's works from the 'Nigeria' series were sold individually and are spread all over the country, if not the world. Lawrence was already a recognised figure, so this was not a body of work that gained a lot of attention.

I think in the last few years, people are rediscovering the fact that Lawrence was a prolific artist and realising how much he really did. Even though he's strongly associated with 'The Migration Series', he did so many other paintings that should have received strong attention.

It's the same with the Mbari Club works. Scholars are recognising that while African art in most museum collections tends to be traditional, with more sculptures, masks, or masquerade objects, artists in Africa and those of African descent are still creating work, as they have for generations.

I think we're also in a moment where the mid-20th century is gaining attention globally. Sadly a lot of artists are passing away, or getting attention in their elder years. There is a sense that we need to give them recognition because this work was ignored for a long time. Now we're in a place where people are going back to see that the work is amazing, and we should recognise it.

NPWhat do we know, based on your research, about what compelled Lawrence to take these trips to Africa in 1962 and 1964? Was he invited?

KGThere were a few things. Even before this period, Lawrence was fascinated with African art. He would go to the Met or MoMA and see these works. He would go to the Schomburg Center. He was doing his own research. He gave lectures, talking about how so much of the work of all these incredible European artists came out of their excitement about works from the African continent.

I've seen letters where he's clearly expressing interest in wanting to go to Africa—he wanted to see it for himself. He felt that Africa was the birthplace of art. I think when you combine that with the moment of the sixties and the civil rights era, and where you're seeing so many countries gaining independence, there was a world context where these countries were being recognised for their cultural contributions.

In 1961, he was invited by the American Society of African Culture (AMSAC) to visit their newly opened site in Lagos. They had included some of his 'Migration' and 'War' series. There he met artists and was connected with Ulli Beier, who was one of the co-founders of the Mbari Club.

They also brought his exhibition from Lagos to Ibadan, where he started conversations as part of a whirlwind tour, meeting with artists from Ethiopia and other parts of West Africa. This caused him to really want to go back, which he did in 1964.

NPFrom an aesthetic point of view, do the 'Nigeria' works look different from Lawrence's other works? Can we discern him trying anything new with his palette or technique? What makes the 'Nigeria' series stand out?

KGHe kept his aesthetic—he was very much an established artist who knew his techniques. What I think makes this series distinct is its visual dynamism. So much of it focuses on the market—you get a sense of the energy and chaos of the market, an idea of just how many people were around him. You see how important colour is to him.

He wasn't changing what he was doing, but he was reflecting on what he was seeing around him. For example, you see women carrying these giant plates on their heads to sell food. You see open-air butchers and people carrying live chickens. You see a way of life which, for Lawrence, was very different. I think it was both different and familiar. He was around all these Black people, and there was this distinction because he was American.

I imagine he saw a lot of similarities to the small fruit vendors and butchers in Harlem and Brooklyn, and experienced similar sounds and smells. I see him trying to capture this visual energy and excitement and difference, but within his continued style.

NPThe show is organised across five sections. What were you trying to achieve curatorially in structuring the exhibition this way?

KGI was trying to find these narratives within an overarching narrative. There are three that really overlap—the Black Orpheus journal, the Mbari Club, and Lawrence's time there. But even within Mbari, you've got all these stories which are overarching.

I tried to break things down in a way that the visitor wouldn't feel overwhelmed or that they couldn't grasp things, or that they needed a PhD to get it. I wanted to make it so that you were excited by seeing the work, and that you understood how these objects came together in a thesis.

There's Lawrence's moment there, but that's not separated from the Mbari Club, where there were artists who were a part of the workshops, part of this bigger community. And within Nigeria you have multiple spots—there is Lagos, but there is also the Zaria School that is somewhat distinct. Things were happening across different cities, but they were connected through the journal.

In addition, there were artists in Black Orpheus who were not from Nigeria but were part of this moment where artists from the African continent were going to school, either on the continent or in Europe or the U.S., trying to create this very modern or contemporary kind of postcolonial language.

They were asking, 'Who are we now that we still recognise and connect with the contemporary art zeitgeist but at the same time, come from so many art practices, legacies, and traditions?' They were trying to promote their heritage—which they were told was not important—in a contemporary way.

They were asking, 'How do I fuse those ideas together?' But Black Orpheus wasn't just focused purely on the African continent or the African diaspora. You also had artists from Asia and Latin America. It really was this amazing moment of countries going through a transition from colonisation.

NPDuring this postcolonial moment, you have this intriguing personage in Ulli Beier, the German editor and scholar who was instrumental in promoting these artists but may have had ties to the CIA.

KGThere is this idea of a so-called 'soft diplomacy'. I think art was very much a part of that. Certain artists were probably aware that the money funding the journal and organisation wasn't exactly clean. I think they knew it was part of a larger political struggle, part of its propaganda. But I don't know if most of the artists who were supported with it knew, or really cared, because it was an opportunity. The issue with the CIA can often overshadow what the journal and workshops were trying to do.

NPThere aren't many women represented in the show. Was it that they weren't involved, or have their stories and work been elided from the history?

KGIt was probably a product of that moment. Women were at the workshops and all of it, but I don't know if women were encouraged much to be artists. With Susanne Wenger and Georgina Beier, both of whom were born in Europe, there was a level of access and privilege—women being artists wasn't seen as quite a strange thing in Europe. A lot of the schools for visual art also didn't come about until a generation before, so I think it was more a product of the times.

NPWhat do you want visitors to take away from the exhibition?

KGI would like them first and foremost to take away the names of artists that they do not know. Whether or not they liked the work, I would like to introduce them to artists who I think did incredible work and made a significant mark on the contemporary art of their time.

I'd also like visitors to think about how we shouldn't pigeonhole artists into a few works, or one body of work. Artists shift and change throughout their career. Too often, I think, we promote only one aspect of their art. I want people to understand that this work is not just visual. We have music and dance as well—it's entirely multisensory.

Lastly, I want visitors to rethink how they see or understand African art. There are hundreds of thousands of different cultures, and these artists continue to practice, they continue to evolve, and they continue to exist. —[O]