Lam Tung Pang and Abby Chen

Abby Chen, Lam Tung Pang, and Dr Alpesh Kantilal Patel (left to right). Courtesy Blindspot Gallery.

Abby Chen, Lam Tung Pang, and Dr Alpesh Kantilal Patel (left to right). Courtesy Blindspot Gallery.

Born in Hong Kong in 1978, Lam Tung Pang is known for his paintings and drawings on plywood, along with site-specific installations, sound works, and videos that embody relationships between humans, nature, and the built environment. In the large-scale painting Centuries of Hong Kong (2011), for instance, which is housed at the Legislative Council of Hong Kong, pale colours are dispersed across four plywood boards to form a seascape interrupted by mountains and a cluster of tall buildings; figures and trees are dotted across the land, while boats drift across the sea.

Influenced by traditional Chinese ink painting, Lam deals with history and memory through poetic vistas in traditional and non-traditional materials, such as nails, sand, and plywood, creating representations of contemporary society in flux that often embody his inner psyche. This was exemplified in a project the artist undertook upon the invitation of Abby Chen, who is the head of contemporary art at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

At the Chinese Culture Center of San Francisco, where Chen was previously curator and artistic director, Lam's exhibition The Curiosity Box (13 June–21 December 2013) included work that the artist created in his New York studio and apartment where he stayed during a three-month residency, transforming it into a 'non-public, but at the same time non-private space' with objects, drawings, video, and fleeting activities such as cooking and travelling that reflected on his time in the U.S. In San Francisco, Lam continued the project by including works created in the apartment along with video, photographs, and a group of sketches of the Rocky Mountains with found objects that he created in response to the 58-hour train ride between New York, Chicago, and San Francisco.

The Curiosity Box project was expanded in Hong Kong with The Hometown Tourist, for which Lam stationed himself at New Capital Hotel in Wan Chai for one month, turning his room into a 'suitcase' that could be visited by appointment between 1 June and 12 July 2015. A parallel exhibition was held at Counter Space in Zurich (30 May–8 July 2015), where the artist sent letters and souvenirs obtained through his aimless wanderings in the city. Through this experience, Lam reconstructed his connection with the city in order to reflect on the dramatic changes that it has seen in recent years, and will continue to see in the years leading up to and beyond 2047, when Hong Kong's independence from China is set to expire.

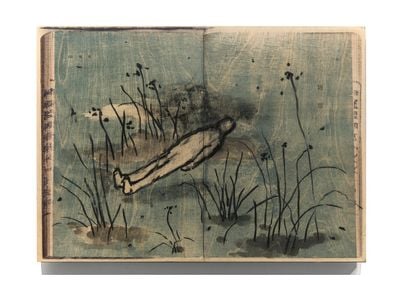

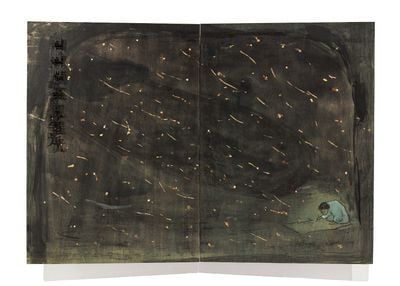

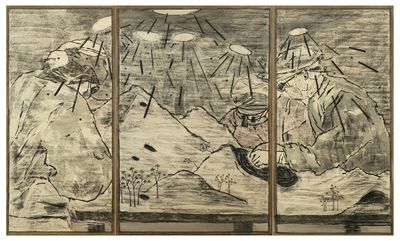

Abby Chen, who has worked with the artist for over a decade, curated Lam's current exhibition, Saan Dung Gei at Blindspot Gallery in Hong Kong (26 March–11 May 2019)—a non-linear narrative made up of paintings, installations, video sculptures, kinetic projection, and found objects that portray a 'the allegorical journey of an itinerant traveller'. The meandering, magic realist works are rendered in pale tones that capture surgeons in scrubs operating on mountains (Landscape in operation, 2018), disembodied chunks of land contained by halved spheres (Wandering in potted landscape, 2019), and pale, lifeless fireworks (Shining Stars in Cave, 2018). Inspired by a 20-minute train ride through a dark tunnel that Lam experienced aboard the newly instated high-speed railway from Hong Kong to Beijing, this foreboding collection of works deals with the fleetingness of memories, as reflected by the drastically modified landscape.

In this conversation, Dr Alpesh Kantilal Patel, visiting scholar at the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at New York University, and associate professor of contemporary art and theory at Florida International University (FIU) in Miami, speaks with Abby Chen and Lam Tung Pang about the influences behind the works in his Hong Kong show.

Let's start with the title of the exhibition, Saan Dung Gei. Could you please give us the title's literal translation, and explain where it comes from?

LTP: We didn't come up with the title first, we came up with the idea of putting some existing video works together in response to the gallery's space. We had been structuring this exhibition for around a year, and when discussing the space with the curator, the approach was more rational in terms of how to construct the exhibition. The emotion was missing until I experienced this ride on the high-speed train from Hong Kong West Kowloon station to Beijing in early November 2018. I found it was important for the exhibition to provide the chance for those emotions to come up.

Before I went on the train ride, I had the idea to write a book called Saan Dung Gei, which is romanised Cantonese. The idea of Saan Dung Gei is the journey someone makes to visit a cave, and when we talked about translating the title, I thought it should just be written as Saan. But for someone who doesn't understand Cantonese or Chinese, they may ask what 'Saan' means, so I used the whole phrase instead, but without an English translation to go with it. If you don't understand, you don't understand, in which case you have to ask—that's my approach.

AC: It was very important to me the way Tung Pang insisted on using romanised Cantonese for the show's title, which was one of the many forms of resistance and holding on to his identity.

There is a lot of different media in the show, from film and video to more traditional painting; but the paintings are sometimes installed in an unusual way, displayed almost as if they are books to be read. Could you talk about the different elements in the exhibition?

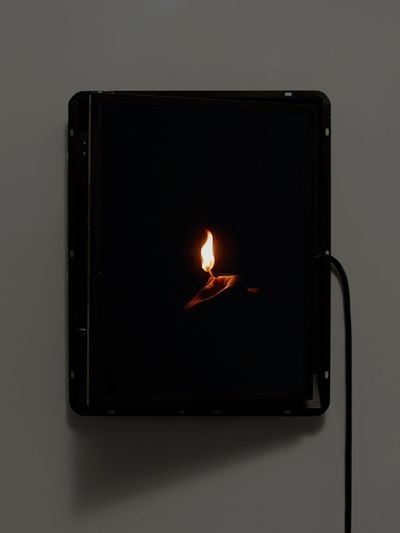

LTP: Perhaps we could start with Hope, which dates back to 2006, when I moved back to Hong Kong from London. Hope was originally a small square painting containing a drawing of a hand holding a burnt candle with a mark on the wood, which I created during my time in London. When I returned to Hong Kong and did a residency at Lingnan University, I created the piece in video format, showing matches burning out repeatedly. The original setting for the video was a projection on fabric, next to an air conditioner. At that time, the piece was just a very abstract idea that did not respond to any context, but actually has a double meaning: it is about how I survived as an artist when I graduated from Central Saint Martins, and also remembers the time when John Paul II passed away, when a lot of people came out onto the street holding candles.

Abby, you felt strongly about including Hope in the show, right?

AC: Yes, because first and foremost I have never considered Tung Pang as a painter, or a painting-focused artist. I always thought of him as multidisciplinary. A lot of his work is very performative or results from performance. For me, the idea of showcasing the versatility of his practice—and highlighting some of his strongest pieces—was very important. If you go to Mill6 or the Legislative Council, you do see his large-scale paintings, but I have never considered size as mattering that much—I have always had a problem with the way people view size as being the weight of an artwork. The Hope video, for me, carries a lot of weight, though it is small in size. The lighting up and burning out of the matches felt like a start, or a preface, to the exhibition—the start of a chapter.

The exhibition is set up so that there's no beginning or end, with a structure that is cyclical—you can start with the Hope piece, or end with it.

LTP: At the very beginning, when I visited the space, I imagined obstructing the view to the gallery so that when the audience stepped out of the lift their view of the gallery would be blocked. The audience would then have to make a choice of going left or right to get into the space. Of course, it doesn't matter whether you go left or right, since you end up in the same place. But what is important is the choice. This idea relates to my own experience; every day is like this.

There are dualities throughout the exhibition; moments when two opposing feelings come out of a work in a cyclical way. Going back to this idea of a cyclical structure behind the show, I am reminded of what Édouard Glissant implies in his writings about circularity—that there's a potential for change within a cycle that offers openness rather than a closed loop1.

LTP: It's not only about a circle—there's a lot of crossing within the circle, and that's why I took all these gaps in the gallery setting and opened up the rotating projection in one of the rooms, where there's a gap from where the light goes through and disturbs the other side. A gallery usually wants perfect lighting, but in this case I introduced the rotating projection to disturb the painting.

Our initial plan was to put multiples of the same Hope videos in the space, but when I shot the video for Hope in 2006 and saw the pile of matches on the floor, I suddenly came up with this idea of freezing the time-based moment into a framed, used oily thing to stick those matches on the surface, then marked with a year, from 2006 to 2018—the work totals 13 paintings, all with oil and matches on the canvas. I have been asking myself what the difference is if I make a video or a painting of Hope. Hope is a sequence of still images, and that's why when you look at the video, it looks like a still image but it changes a little bit in between. For me, time in painting is unlimited. The time difference between video and painting annoys me a lot, but at the same time I really like to work with video because of the limit on time connected with a video's structure, and the way you can play with the sequence of images.

Take, for example, the huge video projection on paper, A Day of two Suns (2019), which shows layers of footage I took from time to time while walking, including birds, rocks by the seaside, a pier, a boat, and a man standing in a shopping centre. The video is about one minute, but is set on a loop; once the sequence repeats it becomes timeless. It is about a play with the idea of time, all the time.

A Day of two Suns is an interesting, complex piece—even just in relation to how the installation has been put together, with that looping video you mentioned projected onto six large hanging sheets of diaphanous paper using four projectors, with two on either side of the screen. You can see the mechanisms holding all these papers together and it doesn't seem all that sturdy.

LTP: I always insist on leaving the mark of the installers and technicians who help set up the piece. When I showed the work in Shanghai there were a lot of workers who helped me put up that piece (The Shadow Never Lies, Shanghai 21st Century Minsheng Art Museum, 29 April–31 July 2016). They were trying to be very careful, measuring everything and holding the papers straight, so they clipped all these different things on the paper. When I looked at how they set up the paper, I found in all their touches a temporary structure, such as the taping, which they thought was just to measure the work. It's similar to the bamboo scaffolding around the buildings in Hong Kong, I think that's beautiful, unsettling—it doesn't exist for long, it's just temporary, but I think that's the most beautiful part.

That's one dimension of the piece, and the other is about the footage that I took to make the video. I usually sit in the park or wander around the city and film, not necessarily in Hong Kong. When I travel, I still do that kind of filming. I have collected a lot of this footage. When I put it together it's a layering of time and space onto paper. In A Day of two Suns, the day is the paper and the sun is the projection. But in the Chinese title, Yat Leung Ting, it's one sun two days, because you have two images.

At the bottom of the piece you also arranged plastic fish and little toys, including a solar-powered, dancing flower. How did these end up in the work?

LTP: The video comes from that experience of walking in the landscape; of wandering around and capturing something. All those objects are part of that experience. A Day of two Suns and the train piece, Saan Dung Gei Turns (2019), are core elements of the show, and there are some other elements around them that could be changed in different contexts. This is how I believe the work stays alive, as long as the artist is still alive. I remember one day, at M+, they asked me how to preserve a neon piece that I did, titled Shaking China (2008). I'm glad that I had a direct conversation with the conservator. She just tried to record everything, and put down my intentions as part of the conservation.

Saan Dung Gei Turns also has a child-like element to it, in relation to the railroad track. There are moments like that throughout the exhibition, where you have these little men that are embedded within paintings that are humorous or playful. There's an element of naivety to them.

LTP: For those elements, scale is very important. Even for the video, Hope, you notice it comes with different resolutions, because in 2006 the common resolution was not HD, but a lower resolution, and the one I filmed through 2018 and 2019 was completely HD. For me, different resolutions are like different scales. People who use a scale model are very insistent on having the right scale, but I'm not, because different scales express different things. Scale is always a factor of my work, and in Saan Dung Gei Turns, there are two trains of different scales that run around the freestanding wall.

Another loop.

LTP: Yes. For this work, I put the train track through the room in both a tunnel and in open space, so that when you look at the train it is as if you are running between two worlds. There's also an Otaleo clock installed nearby that never reaches 12, so you never reach another day. I put all these elements together as a whole setting.

Your work consists in part of these 'traditional' landscape paintings that are actually not so traditional, even if the style invokes the history of ink painting. These are sculptural works, with different figures and models applied to wooden surfaces that narrate uncanny scenes, like mountains being operated on by surgeons.

Could you talk about how you go about juxtaposing these different materials and narrative elements together? The surgeons pop up a lot in your works.

LTP: Yes, they do. They relate to my experience of being under the city in a train, and not being able to see the landscape. I feel that everyone in the city feels that the landscape is being modified, or changing. One journalist commented that in Landscape in operation (2018), the surgeons appear to be helping the landscape, but I said that actually it was because when I was underground I felt as if someone was operating on my body, and I didn't know if they were going to kill or save me.

The landscape for me is a metaphor for the body. It's also part of the structure of the book that I was supposed to write, Saan Dung Gei. When Eye and Hand—the characters I created when thinking about writing Saan Dung Gei—walk through the tunnel, it's as if they've lost their memory, and when they come out of the tunnel they sit in front of the window to reflect on what they have lost, and question whether they are losing their memory. The window becomes the window of an operating room in the three paintings, Forming the landscape (2018), Self-operation (2018), and Landscape in operation (2018), not that of a house or an apartment.

This makes me think about how philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty considered bodies being connected to their surroundings2. But this is not how a lot of the West operates—there's this huge division between humans and land, and humans and animals as well. In your work, it seems that body and land are intertwined, but at the same time threatened.

AC: This is discussed in my curatorial statement. In Landscape in operation (2018), are they really operating? Is the mountain sick, or does it just need a quick fix? It's a highly traumatised image—the mountain is rendered in very bleak tones, which is a big contrast from what Tung Pang used to do. His previous work always included playful humour and bright, colourful buildings with star-like lights. It's very clear that something might be wrong in the scene—it's very pale and lifeless. For me, it's less about the painting itself—it's a mood he's trying to capture, and that mood seems to permeate the show, such as the pale firework in the large-scale video piece, A Day of two Suns. The works constantly reference each other.

Maybe this is a good time to talk about the role of the curator, which is an important element of this exhibition, along with how the works on view build on previous projects that you have done.

LTP: Yeah, it's very important. Unlike other curators, when Abby came to the studio, she looked for the artwork that was not there. You know how the art world works: once artists are doing something, they are labelled and they have a style that they repeat until they can be found or recognised. The first time I cut off my style was when I was making the polar bear series. Everyone—particularly the gallery—was expecting me to create more polar bears, so I just stopped making them. I started a painting that I was going to title The Last Polar Bear, but then I just stopped making them. After that I started making Chinese landscapes and I did a big show at Hanart TZ Gallery in 2011, but then I cut it off again. I just felt I was not the kind of artist to always repeat things. Abby saw that exhibition in 2011—she even wrote something about a few of the works in it.

AC: I did, but then that was because I saw your other work. It was only because I saw your non-painting work, that I understood your painting work. It was the beginning of our long-term collaboration.

The moment I stepped into his studio for the first time, I could tell he was part of this lineage of master painters from Hong Kong, from Lui Shou-kwan and Irene Chou to Wucius Wong. And I thought, okay, just another great painter that doesn't need coverage because a lot of people are studying that already. We had a candid conversation, and later on I flipped through his monograph and realised that he didn't just make paintings. And I thought, is this the same guy that I went to visit?! I did not see this! Later on, of course, I went back to his studio and saw a lot of different things. But initially, my attention was grabbed by his large paintings—they have a presence. He invited me to write about his other works, and then the painting started to make a different kind of sense to me, as containing all these practices that sort of culminate into one medium.

Later on, Tung Pang finally made the decision to overcome his flight phobia and come to the United States for a residency, as part of his Asian Cultural Council Fellowship in 2012. Somehow it felt right at the time that he should visit New York—in a selfish way I was curious about how he would see and experience America. The goal for that trip was for him to go to the Met, and some other American museums to see their masterpieces in Chinese and Japanese painting. That was when I was the artistic director of the Chinese Culture Center in San Francisco. I made it very clear that I couldn't do a show for him like what he'd had in Hong Kong, with all his paintings in a gallery setting. But I went to visit him, regardless, in New York, and I saw all this new work in the studio space he was living in—not paintings, but mainly drawings, objects, writing. On the toilet bowl he had written, 'One country, one system'. The works literally felt like they had grown out of the walls. The space was so magical and full of energy.

Abby, I thought about how to describe your curatorial approach and came up with 'purposeful, present absentness'. You are purposefully hands-off, which might seem as if you're not involved, but relates more to the relationship you both share, and your history of working together. You're curating over the long-term—it's more about conversations and developing ideas.

AC: Well, Tung Pang has a lot of ideas. Initially he was working on referencing Japanese painting. When I was working with him and we were looking at this space, I knew it wouldn't work for a lot of his existing work, but I knew that he was going to create something great. And he knew it, but I didn't know what the trigger point would be. These are the times when you just have to wait. A lot of things were already in place—ideas had accumulated over the years, and had become intuition.

So when was the turning point for this show?

AC: Last year, Tung Pang took a train ride on the high-speed rail to China from Hong Kong, and that changed everything. Four months of intense production followed; the train ride really stimulated him, and I had no idea how to deal with it at that point, because he was moving into a new emotional state. The stuff he was producing was drastically different from what I imagined it would be. I wondered how it was all going to turn out. I had my own share of anxiety and worry, and I knew he would pull it off, I just didn't know how. By coming to Hong Kong, I became his first audience. Because I have known him for so long, I finally figured out what he was trying to do, which was to deconstruct that intense moment in the tunnel, and what eternity is.

It seems that being in the tunnel—that non-space—was a pivot point.

AC: But also that heart-stopping moment of being trapped in that dark tunnel. It sort of encapsulates everything that he has been doing over the past years. The moment was frozen in that tunnel, and everything else got summarised there. I feel like it was a kind of conclusion, or last episode.

LTP: I don't feel the stress that comes with the usual process of curating like with other shows. Our conversations have just become a habit. As I told Abby, we are like each other's psychologists. When speaking on the phone in the lead-up to this show, we didn't talk about Saan Dung Gei so much.—[O]

—