Maree Clarke Connects Country, Culture, and Place

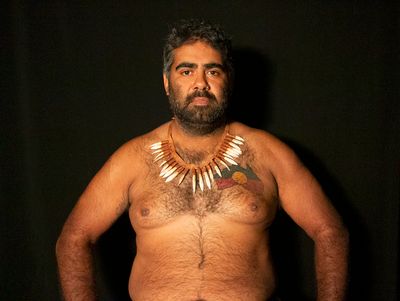

Maree Clarke. Photo: Julian Kingma.

Maree Clarke. Photo: Julian Kingma.

Maree Clarke's poetic, personal, and political practice is a type of cultural truth-telling, steeped in memory and Country while deploying photography and new technologies to tell stories of past, present and future.

Hailing from north-western Victoria, Clarke is a Mutti Mutti/Yorta Yorta and Wemba Wemba/Boon Wurrung artist who reclaims ancestral art practices and Indigenous rituals through multimedia and storytelling.

Trained as a photographer in the early 1990s to document the lifestyle of the local Koori Aboriginal community, Clarke has worked as an artist, curator, artistic director for the past 30 years. Across her work, she has explored customary ceremonies, rituals, and language of her ancestors, casting her family members in an array of lenticular prints, and worked across media, whether 3D photographs, holograms, sculpture, jewellery, and video installation.

Clarke is described as 'a pivotal figure in the reclamation of south-east Australian Aboriginal art and cultural practices' in her current survey exhibition Ancestral Memories at the National Gallery of Victoria (25 June 2021–6 February 2022), which includes a 63-pelt possum skin cloak mapping countries connected with her family, and the striking Ritual and Ceremony (2012), 84 black-and-white portraits centring on white Kopi mourning caps.

As Clarke stated in the catalogue for Defying Empire, the 3rd National Indigenous Art Triennial (6 May–10 September 2017) at the National Gallery of Australia: 'We haven't lost anything; some of these practices have just been laying dormant for a while.'

In 2020, Clarke was awarded an Australia Council Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts Fellowship. The same year she was announced as the artist commissioned to create a line-wide art work across five new metro tunnels across Victoria, connecting this mammoth project to place and belonging of First Peoples and their 67,000 years of living culture. Clarke has understaken large-scale public projects in the past, painting a tram in 1988 to advertise the Koorie Heritage Trust.

This year, Clarke is among the eight artists from Australia and Japan included in Reversible Destiny: Australian and Japanese contemporary photography at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum (24 August–31 October 2021), a group show considering the role of contemporary photography amid global upheaval, frailty, and uncertain futures.

In the exhibition's bilingual catalogue, author Tony Birch writes a parallel text about walking or perambulating in Kyoto, Tokyo, Dimboola, and Birrarung (the Yarra River, Melbourne); he mentions the scars of colonial violence, and paying respect to the home of others while running the five-kilometre track circling the Imperial Palace in Tokyo.

'I reflect on this place and feel gratitude', Birch writes. 'I think of home, of my river, of my many running tracks, decades in the making. At this moment, at this very moment, I can be there, by the Birrarung, and I can be here in Tokyo. Together.'

Writing of interconnection, Country, and place, Birch takes us elsewhere. So does Clarke in her haunting images of ghosted figures superimposed on a massacre site in Road to Warrakoo (2011), or in The Long Journey Home (2018), a series of photographs showing Clarke's family members in a canoe made of reeds wearing painted kangaroo skins.

In the following conversation, Clarke talks to Reversible Destiny's curators Natalie King and Yuri Yamada, elaborating on her community origins as an Aboriginal educator, the revival of possum cloak rituals and kangaroo tooth necklaces, as well as passing on knowledge to future generations.

NK & YYLet's start at the beginning and your pathway to becoming an artist. Was there a particular incident or some inspiration that occurred that led you to a creative life?

MKI started out as an Aboriginal educator in Mildura, where I worked for nine and half years at the local primary school that I had attended. This position came up in the late 1970s when the Victorian Aboriginal Education Association were employing Aboriginal people to work with local Aboriginal school kids.

I got the job in 1978. It was my first real job. I worked in the library for a long time and then eventually started working as an Aboriginal educator through the Victorian Aboriginal Education Association.

In 1987, Mildura Aboriginal Co-Op put out a call to set up an Aboriginal art and craft shop, and I left the educator position to do so. I didn't know anything about art—I had no formal training and left school at 15.

For that job, I travelled up to Alice Springs, visiting different communities like the Mutitjulu community near Uluru to buy products, and then back to Victoria, buying from local Aboriginal artists here. The art shop was really successful, supporting local Aboriginal artists and also artists from other areas. That's where we got these great batik Ernabella T‑shirts and beautiful screen-printed posters. You don't see them around much these days.

When returning to communities with traditional designs by artists from their own areas, people said things like, 'Oh my art makes sense to me now.'

My brother made these beautiful hand-painted jewellery pieces for the shop. I still have a box of timber that I've had for at least 30 years—he gave me some to make jewellery myself. My first pair of earrings took me about 15 goes before I was happy enough with the design to show them in public.

I sold that pair of earrings for about 25 dollars. Jim Berg, founder of the Koorie Heritage Trust, used to buy a lot of our jewellery. They now have one of the largest collections of it.

I went from painting jewellery, where my smallest brush had two or three hairs, to painting the first green and gold tram in 1988 advertising the Koorie Heritage Trust, and then basically it all kicked off from there, from painting billboards and doing public art commissions with my sister-in-law Sonja Hodge and Len Tregonning.

We painted the tram poles in the city square in the early 1990s. Then, Sonja and I wanted to hold an exhibition so we just contacted all our artist friends and approached ATSIC (Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Commission) to see if we could use their building.

They installed tracking throughout the building, and we had a really successful sold-out show. We didn't take a commission, as we just wanted to hold this great exhibition and support our artist friends, which we did.

NK & YYYour grandmother was from the Stolen Generation, taken to the Cootamundra Domestic Training Home for Aboriginal Girls. What was it like growing up in Swan Hill in the early 1960s, and sleeping in a suitcase in a tent along the Murrumbidgee River that became the source for your lenticulars in Reversible Destiny?

MKI don't really have any memory of living in Swan Hill or Balranald Mission because I was younger than two when we lived there. I was born in Swan Hill, but then we moved to the mission in Balranald and that's where we lived in the tent and my bed was a suitcase.

There were lots of other Aboriginal families living down on the flats near the river and my grandparents also lived not very far from us in a humpy. I've got photographs of my grandmother and grandfather, aunts and uncles outside their tin shed house.

Both my parents were born in Balranald and then we moved to Munatunga Mission, which is the Mission in Robinvale, and then my mother, my brother, and I all contracted tuberculosis.

My older brother, who passed away a couple of years ago, Sydney John, said he had this memory of all the black fellas being lined up and all the big black cars driving down into the mission. They must have been testing for TB and the next day one of the big black cars came back and took me, Mum, and Ray and brought us to Fairfield Hospital where we stayed for two years.

NK & YYYou were in hospital for two years?

MKYes, I didn't get out until I was four, and then we were sent back to Mildura and the welfare would pick my grandmother and Sydney John up from Munatunga Mission in Robinvale and drive them to Mildura to visit us in the hospital. That's how we ended up in Mildura, because the welfare ended up getting Nan a house in Hornsey Park in Mildura, so they didn't have to drive her every week to visit us.

I only have one memory of when me and Mum were in the chalet, which is a section of the hospital that had flywire screen all the way around, because apparently with tuberculosis you've got to have a lot of fresh air. The beds were on a verandah, and I have one memory of being there with my Mum.

I would have been about four and a half. My Dad was off shearing somewhere, so I don't remember him being around a lot because he travelled around New South Wales shearing with his brothers.

NK & YYIn your work, you are activelty regenerating cultural practices, especially ones that have been lying dormant. Could you talk about that?

MKOne of the first things I did was the Cloak Project (2005–2006) for the Commonwealth Games in Melbourne, where I worked with Vicki Couzens, Lee Darroch, and Treahna Hamm. We basically split the state of Victoria in four, and all worked in different regions to take traditional designs back to communities and teach cloak-making.

When returning to communities with traditional designs by artists from their own areas, people said things like, 'Oh my art makes sense to me now.' To be able to give back this skill that hadn't been practiced for quite some time in communities was very special.

A few years later Vicki, Lee, and I were in an exhibition at the Melbourne Museum and for years I'd wanted to make a kangaroo tooth necklace. I'd been into the Melbourne Museum, had a look at historical necklaces, took detailed photos, and worked out how to put the necklaces together.

There are only six historical cloaks left in the world, so it was important to pass on knowledge and continue possum skin cloak-making.

We got a kangaroo tail and Len Tregonning worked out how to get the sinew out of the tail, and then we spent the next couple of weeks preparing teeth, leather, sinew, and ochre. We put the two-tooth necklace together first and then we had enough time in the lead‑up to this exhibition to put together the 75-tooth necklace.

Now we have taught my nieces and nephews how to take the sinew out of the tail of a kangaroo, how to bind the teeth, how to lay it out, put it together, and prepare all the parts to make 75-tooth necklaces. It's about sharing cultural knowledge and creative art practice, always.

NK & YYCould you talk about the significance of the ancestral possum skin cloaks, which have been a pivotal motif in the reclamation and revival of possum skin cloak making in the south-east?

MKThe possum skin cloak is an important part of Aboriginal culture in south-eastern Australia. Because of our weather in the south-east, we needed something to keep us warm, but it also marked who you were; your connection to Country, culture, and place.

Everybody would have had a possum skin cloak made over their lifetime, and at the end of your life, you were wrapped and buried in your possum skin cloak. There are only six historical cloaks left in the world, so it was important to pass on knowledge and continue possum skin cloak-making.

After the Cloak Project for the Commonwealth Games, we have since gone on and taught cloak-making up along the east coast, all the way up to Newcastle, to Central New South Wales, and South Australia.

At least 35 of the 38 language groups of Victoria are now teaching cloak-making. It has now become more commonly included in community baby naming days, ceremony, and funeral practices. When somebody passes, we make a possum skin cloak to wrap and bury them in their cloak.

I had a cloak made for Len's 60th birthday, and when he died, I had family and friends come around and mark the cloak with his totems and everybody rubbed ochre on their hands and marked the cloak with their handprints. I then went into the funeral parlour and wrapped Len in his cloak.

When my brother Sydney John passed, we all came together as a family, sewed a cloak for him and he got to use the cloak for a couple of weeks before he died. We wrapped him in it, and he was cremated in his cloak. It is so vital to bring back these cultural practices.

NK & YYYou have a dexterous capacity to work across media, from photography, jewellery, and the kopi mourning caps to more recent glass blowing. Does the concept drive the medium or how do you work so fluidly across all these forms?

MKSometimes I don't know what I'm going to do until I've been invited to be part of a show, and if it's new work, then it's a lot of thinking about what story I want to tell through art. I'm always trying to think of new creative ways to tell stories using new and different mediums.

NK & YYIt sounds like there is a lot of labour and experimentation in your practice. Can you describe a typical day in your studio?

MKI am always working on multiple projects at the same time. At the moment, I'm working on a new jewellery collection with Blanche Tilden for Radiant Pavilion, and so out the back I've got all of these echidna quills that have to be sorted, sanded, dyed, and drilled. They're all sitting in dye baths along with quandong seeds.

The next part of that process is to hand-wash them in a bucket, then put them in a bag in the washing machine to do a whole cycle. Right now, I am focussed on readying all the individual quills for this next jewellery collection, but that's only one part of my day—there's the emails, preparing for speaking engagements, making new PowerPoints, the Zoom meetings and lectures for universities...

I'm also one of the judges for the new NGV Contemporary building. I am also creating work for five new metro train stations and for the Tarnanthi Festival at the Art Gallery of South Australia (15 October 2021–30 January 2022). Then I have these three great public art commissions with Broached Commissions, where I'm collaborating with people like Daniel Crooks, a multimedia artist and filmmaker, and Trent Jansen, who is a designer.

Trent and I have designed these beautiful seats made out of charcoal, river reeds, and my beautiful sticks. These will all be cast in bronze, and then I have to spend a bit of time loving-up my three puppies.

NK & YYYou mentioned all the thinking and all the ideas formulating. Do you take notes? What is your process?

MKNo, no, I just think. Sometimes I could be sitting watching TV but I'm not, it's just white noise, because I'm wondering how to glue the flowers onto the dresses and what design I might create, and then I have to think about the make-up that I want the girls to wear for the Tarnanthi photo shoot.

This living archive will be for future generations to access and continue making new memories and inspiring the passing on of cultural knowledge and creative art practice.

NK & YYWhat is the process of bringing in other people and family into your practice?

MKIt's to share—to share stories and knowledge and pass on cultural practices, because when we're out there in the backyard studio, we're talking about a whole range of different things.

When I was making the big 63-pelt possum skin cloak in the backyard for my solo exhibition, which was commissioned by the National Gallery of Victoria and at the time my hands weren't working so well, I rang all my nieces and nephews and some other friends, and they all came over.

I must have had about 12 people in my space, and they all helped sew the cloak, which was fantastic. Now, all my nieces and nephews know how to lay out and cut a possum skin cloak and mark it with stories and design.

The Living Archive of Aboriginal Art is another project I'm working on with Fran Edmonds in collaboration with the University of Melbourne. It's a platform that will act as an archive for all the making and creating and documenting that I've done, including research.

There haven't been a lot of images available to community that show process, unless you go into museum collections. This living archive will be for future generations to access and continue making new memories and inspiring the passing on of cultural knowledge and creative art practice.

NK & YYLet's talk about you epic monograph exhibition at the NGV, Ancestral Memories. It was phenomenal to see your early activist documentary photography through to the necklaces and lenticulars.

MKAs a starting point, because the NGV acquired that whole Ritual and Ceremony (2012–2018) collection a few years ago, the curator Myles Russell-Cook talked to me about having this series run like a spine throughout the show. I think it is really beautiful and allows for a flow, plus it looks phenomenal on the black walls.

'It's about sharing cultural knowledge and creative art practice, always.'

We were in and out of lockdown so there were lots of Zoom meetings with the team showing me the exhibition design on the computer fly-through. When I saw the show for the first time, I just burst into tears. I must have sobbed my heart out for ten minutes. It is 30 years of memories, making and creating and sharing knowledge with family and community.

NK & YYThe emotional tenor of the exhibition is palpable and that beautiful photograph of you at the entrance is as if you are holding everyone around you. How did you arrive at the title Ancestral Memories?

MKI had used that title for my glass eel traps because the eel has ancestral memory and I figure, we must too.

NK & YYWhy don't we look more closely at the canoe work The Long Journey Home (2018) in Reversible Destiny. Shall we talk about how you realised these works?

MKThe Long Journey Home was initially commissioned for an exhibition at the Mission to Seafarers. I thought that I would make a three-metre river reed canoe, which is about our connection back to lutruwita (Tasmania).

I researched historical images of Tasmanian canoes, my husband Nicholas Hovington collected river reeds, and a couple of his mates helped make the canoe in the backyard. I initially photographed Nicholas in the canoe, and then I photographed my nieces and nephews in it at Altona Beach.

The guy sitting in the canoe is my nephew Indi. Indi heads up the Koorie Youth Council here in Melbourne, while Aaron lives in Ballarat. Kylie is in a lot of my photos and the little fella Matari is her son. They are all wearing kangaroo skins because in Tassie they use kangaroo skins.

Nicholas painted the kangaroo skins to look like thylacine skins, and we have just found out that the palawa people also had possum skin cloaks made slightly different to ours, and then I painted T‑shirts for the boys to wear.

NK & YYLet's discuss Road to Warrakoo (2011) which is a ghostly, haunting image that looks at the past, present, and future but also relates specifically to massacre sites. Can you discuss your research for this particular work?

MKThe photo was taken up near Lake Victoria in New South Wales and around that area is the largest concentration of Aboriginal sites in Australia. Everywhere you look, everywhere you go there is something. Also, at Lake Victoria there is a huge burial site and when the lake was drained, all these skeletal remains were exposed.

The Barkindji mob ended up wanting it all covered up and made these giant sandbags to cover up all the remains. Lake Victoria also runs into the Rufus River where the Rufus River Massacre happened in 1841, and you can absolutely feel that energy.

Just knowing that history, I thought it would be the perfect spot to do that shoot by using an image of the landscape and superimpose three ghosted people. There is a sense of life and death and mourning embedded in the work.

NK & YYLet's look closely at On the Banks of the Murrumbidgee (2011), the triptych of landscape lenticulars overlayed with your fingerprints. What is your relationship with the Murrumbidgee River?

MKThese works are from the series 'Made from Memory – On the Banks to the Murrumbidgee River'. This work speaks about when my family and I lived in a tent down behind the mission in Balranald and my bed was a suitcase. I travelled back up there, borrowed that tent from the local Scout Group, and at the time, it was at the peak of a flood.

I've had the suitcase for years, it used to belong to my auntie. The landscape is stamped with my thumbprint—it's like it's embedded in Country, in the trees, in the clouds, in the river. Country is in your DNA. You're just embedded everywhere. —[O]

With thanks to Jessica Clark, Assistant Curator and Phd candidate, University of Melbourne for her invaluable assistance with this interview.