Mark Sealy: African Cosmologies at FotoFest Biennial 2020

Mark Sealy. Courtesy FotoFest Biennial.

Mark Sealy. Courtesy FotoFest Biennial.

Born in Hackney and raised in Newcastle upon Tyne, British curator and cultural historian Mark Sealy's introduction to art began in secondary school, followed by formative years spent as an art student at Goldsmiths, University of London. This was a polarised period in British history, indelibly marked by Thatcherism, the 1985 Brixton riots, and the year-long miners' strike between 1984 and 1985.

Since 1991, Sealy has served as director of Autograph ABP (formerly known as the Association of Black Photographers), the London-based independent photographic arts agency founded in 1988 with a mission to promote and advocate visibility for historically marginalised photographers and filmmakers. In his role at Autograph ABP and beyond, Sealy has long championed for the decolonisation of photography to draw attention to hidden and overlooked histories, while embracing difference and disrupting formations of othering.

For almost three decades, Sealy has rigorously developed photography's intersections with social change, identity politics, and human rights, which has resulted in major curated international exhibitions, publications, lectures on photography, and film commissions.

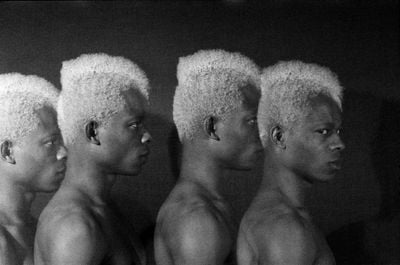

Among these exhibitions are Human Rights Human Wrongs, which featured images selected from the Black Star photo agency's collection of photographs of turbulent events of the 20th century, shown at the Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto (23 January–14 April 2013) and at the Photographers' Gallery, London (6 February–6 April 2015); Rotimi Fani-Kayode (1955–1989), a retrospective of the seminal queer British-Nigerian photographer and activist, marking the 25th anniversary of his death and co-curated with Autograph ABP's senior curator and head of archive and research, Renée Mussai, at Tiwani Contemporary in London (19 September–1 November 2014); and Black Chronicles II (also co-curated with Mussai), exploring black presences in the 19th and early 20th century, through British studio portraiture, first shown at Autograph ABP, London (12 September–29 November 2014).

Sealy collaborated with the late cultural theorist and academic Stuart Hall on Different (2001), a visual and text compendium of around 40 black photographers who approach issues of difference as this relates the history of the photographic image. His most recent publication, Decolonising the Camera: Photography in Racial Time, published in 2019 by Lawrence & Wishart, furthers the discourse on post-racial imaginaries by examining photography, with essays by Alice Seeley Harris, Joy Gregory, and Rotimi Fani-Kayode, among others.

When the organisers made it clear they wanted to focus on African photographers, I made it clear that I wasn't going to jump on an aeroplane and travel around 54 countries selecting artists... that's not how I work.

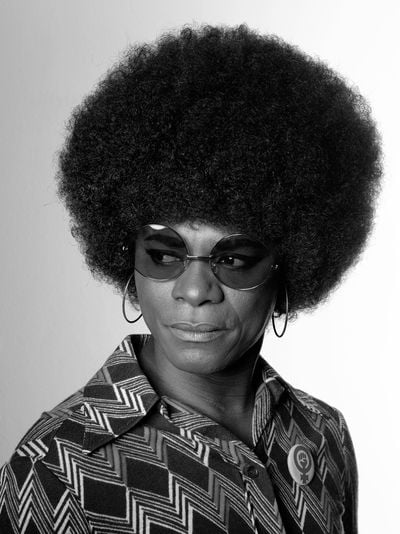

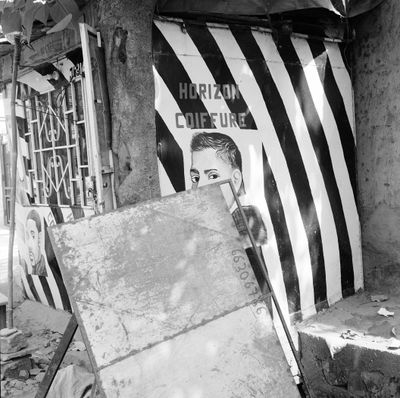

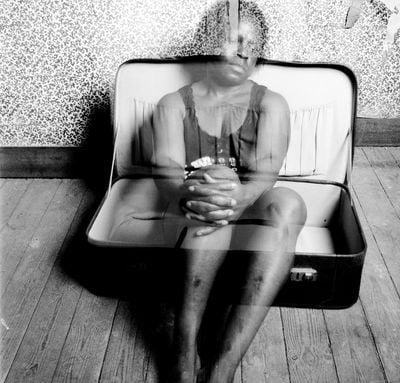

As curator of the 18th FotoFest Biennial (8 March–19 April 2020), Sealy has directed the Houston's city-wide annual photography festival to focus its attention on the continent and its diaspora for the first time. Sealy's thesis African Cosmologies: Photography, Time, and the Other, seeks to use the lens of improvisational jazz to expand on the term 'African' in photography, with the intention to free it from the weight of geographical fixities and well-worn colonial framings. Presenting works by over 30 artists, including Zanele Muholi, Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Samuel Fosso, Faisal Abdu'Allah, Carrie Mae Weems, and Zina Saro-Wiwa, the multi-venue exhibition will also include a symposium on contemporary African photographic arts on 21 March 2020, commissioned projects, and a curated film programme, along with a hardcover publication.

In this conversation, Sealy discusses his beginnings in art in the north of England, the racial politics at work within photography, and how, for his role as curator of FotoFest Biennial 2020, he looked to cosmologies and disobedient jazz as critical tools for disrupting canonical readings of photography.

JDWhat initially sparked your interest in photography?

MSI had a very good set of art teachers who were enthusiastic and empathetic about showing different perspectives, which was fantastic, even though this was in quite a run-down secondary school in Newcastle. This is where it all began, with an art offer high on the agenda for myself and my peers from a very young age. We were encouraged to draw from life, and art was very much part of our basic education. Unfortunately, this is something that is now being pulled from U.K. school curriculums.

After my O- and A-levels, I went onto a foundation course that allowed me to experiment with various art forms—ceramics, painting, and so on. University followed, all through the lens of the wonderful opportunities that state-funded education offered. The key point here is that working-class people like myself, who grew up in the industrial decline of 1970s Britain, had access to a state-run education system that enabled individuals to go to university through grants made available to cover fees and expenses if you had the right grades. This meant that there was much more social mobility for working-class people, or people from different cultural backgrounds, to enter the arts. The risks, in terms of one's career path, were mitigated as one did not come out of university with a huge debt.

One of the most important changes that has happened [in the United Kingdom] for people from different cultural and class backgrounds going into the arts, is the economics of education. There was a sense in the 1980s that art school was a place to become free. How did I escape the idea that I might become a factory worker? It wasn't some great, enlightened, pedagogical discourse. It was quite simple really: an art teacher suggesting I go to art school.

JDWhat did going to art school in the 1980s mean for you, coming from a working-class, British-Caribbean background?

MSComing from the kind of background I came from, it was always going to be problematic for my family to get their head around what going to art school meant, but overall, as long as they weren't feeling it financially, it was okay. I left home at 17 or 18, and in my opinion, people moved away from home at a much younger age in the late 1970s and early 1980s than they do now. Back in the eighties, there was a sense that you could be mobile and fluid—that you were autonomous and responsible for yourself. Going to university meant that the familial umbilical cord was cut, and very few people went back home after this.

Africa is everywhere, and what we need to do is recognise its influence and its complexities across the globe, from China and the U.S.A., to the Caribbean and Europe, along with the multiplicities of Africanness across the continent itself.

For my generation, leaving home and moving towards some form of independence was what people aspired to do, regardless of whether they went down the university or apprenticeship work route. Many of my peers also joined the armed forces as another path to becoming independent. I was the first of my family to go to university, so these were new terrains, although there wasn't a sense that my education was a risk to them in any way, even though they didn't really understand the choice I had made.

Within every society, there have always been cultural elites who have been groomed to go to university through grammar and private schools. For kids coming out of secondary modern and comprehensive schools, there was never a sense that this path was open. So that decision was, in retrospect, a kind of class-based, black-space radical intervention into art school. I arrived at Goldsmiths College in 1982 as the only black student at that time.

JDYour curatorial approach generally centres on race and creating alternative narratives. How has that approach shifted over the decades?

MSThrough the lens of going to Goldsmiths in the 1980s, I became very aware of the whole question of representational politics. Looking back at the politics, this was a highly contested time for black subjects in Britain. The riots had happened in Brixton and other major cities, and there was a sense that the black subject was very unwelcome. For me, this became more intensified by being in south-east London and becoming aware of the frontline politics of that space. This influenced what I was reading, thinking, and who I networked with. London had many more opportunities for discussion around race and politics than Newcastle. There was a sense of grasping opportunities to be active.

Additionally, there were opportunities offered by bodies like the Greater London Council, which fostered important interventions through its ethnic minority arts policies. Even though London was at its height of Thatcherist politics, it still had left-leaning local authorities, such as Lambeth Council. People were still trying to invest in the creative policies that were available and visible in London at that time, and it was about tapping into that energy, when things felt possible.

JDFrom the 1980s to now, where do you think we are at with dealing with race and alternative narratives in curating?

MSIt is an interesting one to consider, as I think some things have progressed in those spaces and some things haven't. Things go around in circles, but it still feels like we've been having these same conversations 30 years on. We are still talking about the lack of inclusion, diversity, and opportunity for people from different cultural and racial backgrounds and gendered backgrounds. It feels as though we've been having these conversations for a very long time; however the world, as we all know, is different.

It would be crazy right now to exhibit contemporary artists without including contemporary African artists or not thinking about the audience and gender balance. I am not saying that these conversations didn't exist previously, but they are louder now. Anyone working in photography knows about LagosPhoto Festival or knows about what's going on in India, for example, because we can get a hold of knowledge systems a lot easier. There's a new dynamic global energy at work.

Photography is still at a very young stage now, and it might take another 200 to 300 years before there is a full history of photography on the table, but we now know—through artists like Samuel Fosso, Sammy Baloji, or Rosana Paulino—that the history of visual culture and making images is being investigated, torn apart, blown up in the air, and made new. If you want to visualise that 'making new' process, exhibitions like African Cosmologies help us along the way.

JDYou are curating FotoFest Biennial 2020, which focuses on African and diaspora photographers for the first time in their history. Could you talk about the process of curating this exhibition?

MSWhen the organisers made it clear they wanted to focus on African photographers, I made it clear that I wasn't going to jump on an aeroplane and travel around 54 countries selecting artists... that's not how I work.

The fortunate thing is that I have been talking to contemporary African artists for at least 30 years, so what I was interested in was to bring some of these old and new conversations together. Within this process, there are some artists I've been engaging with in-depth, and others who have arrived on the scene in recent years—people like Eric Gyamfi, for example. Whether these artists evolve into strong contemporary contenders in the field, I don't know as of yet.

I first showed Zanele Muholi's work in 2010 in Toronto, so these are longstanding conversations with artists and their work. Rotimi Fani-Kayode has been central to the work of Autograph ABP, and we advocated his work at FotoFest in 1992—Houston has always been important to me because of that. Right next door to Fani-Kayode's show was a presentation of work by a white Brazilian photographer called Mario Cravo Neto.

Cravo Neto's work is important because he was totally immersed in Yoruba culture, and he made these beautiful, almost complimentary prints to Rotimi's work. They were worlds apart, culturally speaking—one was from Lagos, the other Bahia—but both were working on the same subject. They were both hugely influenced by this particular dynamic of Yoruba culture and from that moment, I have always thought that we can't keep talking about the continent as some homogenous, locked up land mass somewhere.

This is really about offering up the fact that there are lots of different knowledge systems out there, and we have to start drawing on them by looking at them, examining them, and giving them time to enter into our consciousness.

Africa is everywhere, and what we need to do is recognise its influence and its complexities across the globe, from China and the U.S.A., to the Caribbean and Europe, along with the multiplicities of Africanness across the continent itself. The idea was to put a sign in the ground in the photographic landscape, not through geography but through the contemporary meaning of Africa, encompassing liberation struggles, music, cultural rhythms, diaspora, and writing.

JDIt could be argued that the use of 'Africa' in the Biennial title, African Cosmologies: Photography, Time, and the Other, grounds the show in the geographical and the colonial. How does one depart from this?

MSI agree with you that as soon as you say the word 'Africa' or 'African', a degree of coloniality comes across. It becomes difficult to unhinge, but by using African Cosmologies across this space, we begin a process of de-linking it from those past associations. You also have to recognise that geography is there, even though it does come with a certain degree of baggage.

When artists like Santu Mofokeng, who recently passed away, talks about their sense of being African in that space, we have to recognise that. We can't deny that. Sammy Baloji, when he talks about his experience of the Congo in terms of its histories, we have to also see Europe.

One of the things I am aware of is that we are not all at the same place at the same time, which is why time as a space works for me. Some of us evolve politically and culturally through different moments, so an older photographer like James Barnor talks about his African space differently, from, say, a younger artist like Eric Gyamfi. It's a mistake in my view to try and get everybody on the same frequency. This is why I prefer the idea of cosmologies. It's like jazz, really. There's a space where people come from, and meaning has to be allowed to keep evolving.

This is really about offering up the fact that there are lots of different knowledge systems out there, and we have to start drawing on them by looking at them, examining them, and giving them time to enter into our consciousness. It's not about presenting the best way of entering into visual culture; instead, it involves looking in multiple directions, both up and down, backwards and forwards. This multi-directional perspective is very important, as I am at a stage in my life where I'm thinking that I need to get to a more harmonious space, rather than one of conflict.

JDYou have stated that 'there is a need for artists to be brave and to work in the knowledge of what has gone before but to not allow oneself to be chained to the past.' Are there specific artists or artworks you have included in the FotoFest Biennial who are doing this?

MSEdson Chagas is playing with traditional cultural ideas and progressing them into contemporary conversations, which I think is really interesting work. In Brazil, from a diasporic perspective, there is Eustáquio Neves, who uses the alchemy of photography to make important images, and Dawit L. Petros, who lives between Eritrea and Canada who deals with ideas around mirrors and reflections. From a more senior perspective, Samuel Fosso has been breaking the mould for quite a long time through self-portraiture, political commentary, and historical black perspectives through performative photography, which I think is fantastic work.

From a cultural and political perspective on Egypt, Laura El-Tantawy's work is very strong and evocative, and presents an expanded idea of what you do with documentary traditions. Aïda Muluneh is one of my favourite artists going forward, with her recent work on water for Water Aid, along with Hélène A. Amouzou, who was born in Togo and lives in Belgium, makes self-reflective work. The pulse of all of these artists' sense of self, politics of place, and issues they are confronting is indicative of what one might call a kaleidoscopic shift. I was also mindful of not wanting to exclude artists with more traditional work, like Akinbode Akinbiyi, who is in his seventies and has done work on cities for a very long time. We have to treasure that as well.

JDHow might racial time in photography serve as a lens that posits other ways of seeing at a time of increasing divisions in our society?

MSI hate this idea of negative and positive, but I do charge photography with being loaded historically with an abundance of negative images of black people. Whilst people like you and I are increasingly familiar with artist breaking the mould, the reality is that 30 years on, the archives of photography, the news, and the media still have a certain way of categorising the black subject, which needs to be turned over and is being turned over.

Hopefully, we can use photography as a tool for a much better understanding of black cultural practices and black humanity to close the awful gap that photography has created by debasing the black subject since its invention in 1839. We have a long way to go. We still have very few curators and historians doing this—we can name most of them on our fingers. We lost Bisi Silva and Okwui Enwezor last year... It's great that fantastic younger and different voices, such as Christine Eyene, are coming through. More dynamic players will help the histories of photography going forward. The diversification of this field can only be for the better of everybody.

JDHow do you see photography as a tool for desegregating blackness from a fixed racial position to a more nuanced framing of the black subject?

MSIt seems to me that black people always have to shout loudly just to have a presence anywhere, still. If people in positions of authority tuned in differently and allowed themselves to not know the answers to everything, to flow a little bit more, and to be genuinely open to different ways of using images for creative processes, this would be beneficial to us all.

There's so much pleasure and fun that can happen through de-linking and making different kinds of images or telling different types of stories. If, as curators, we allow that to happen or flow, the impact for audiences will extend to bridging societal gaps and perceptions that people have around the Other, whether they are queer, African, Indian, or working-class and white others.

Conservative ideas around identity formations is something I have always tried to challenge. Bridging the gap and taking responsibility for each other is very important. Photography and empathy are very good bedfellows. If we can just get the resonance right, we might see things differently going forward.

All I am really saying is that I want to encourage a creative conversation, and although it's important to point accusational fingers, as human subjects we are much more complex than history allows us to be. If I could go back in time through the creative process, I would work through music, as photography it seems has got a long way to go and has a lot of catching up do. I am really interested in the disobedient jazz of it all. —[O]