Maryam Jafri

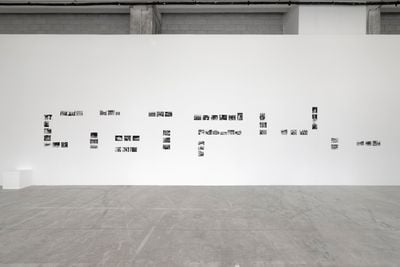

Maryam Jafri. Photo: Kristof Vrancken.

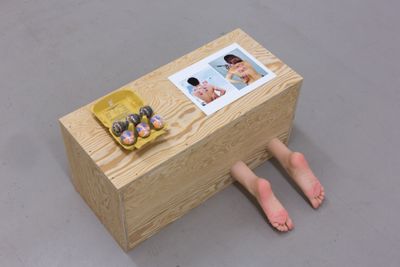

Maryam Jafri. Photo: Kristof Vrancken.

Maryam Jafri's series 'Product Recall: An Index of Innovation' (2014–2015) will be shown for the first time in its entirety in the United States at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, between 10 February and 23 June 2019. The exhibition's title, I Drank the Kool-Aid But I Didn't Inhale, references Bill Clinton's admission to (not fully) smoking marijuana when asked if he had ever broken an international law. By referencing a former American head of state who denied smoking marijuana by claiming he 'experimented with it', but never 'inhaled' it, the artist draws attention to an ideology of having it all without repercussions. Thirteen 'failed' 20th-century American consumer products make up 'Product Recall', exhibited with texts and photos that indicate branding and packaging aesthetics. These range from Kleenex tissue paper laced with pesticides, to Diet Pepsi baby bottles—items that have been 'relegated to the dustbin of history.' The work, as is characteristic of Jafri's practice, invites the audience to consider the hidden significance—and meanings—of archival materials.

For a similar project, Generic Corner (2015–ongoing), the artist has assembled a collection of 'generic products'—consumer products from the 1970s with simple, black and white labelling. The aim of this form of branding—through the eradication of design, marketing, and advertising costs—was to allow for an affordability among consumers that became stigmatised, with these labels—and the purchase of products emblazoned with them—becoming a sign of poverty or of frugality. The project consists of products that the artist has sourced and presented on white plinths, along with still life photographs and a panel of text.

With a BA in English and American Literature from Brown University, research plays a central part in Jafri's conceptual approach, which spans video, sculpture, photography, and performance. The artist's practice often deals with issues related to global capitalism, as seen in 'Wellness-Postindustrial Complex' (2017), a series of sculptures and photo works that examine the rise of Eastern wellness practices in postindustrial societies. Self-care is contemplated by Jafri as being representative of contemporary capitalism, whereby the DIY pursuit of one's wellbeing is a response 'to an age of economic dispossession and social fragmentation.' Sculptures include wooden structures from which silicone feet—sourced from online fetish stores in China—are jutting out, and embellished with acupuncture needles, along with a deep purple yoga mat has been cut to resemble a roll of toilet paper, hanging from a stainless steel holder. Photo works on inkjet paper include people undergoing wellness routines such as cupping.

In this conversation, Jafri comments on the nuances of her archive of failed and predominantly food consumer products in 'Product Recall', as compared to her other archival works.

PNLet's begin with titles. Your show at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles is called I Drank the Kool-Aid But I Didn't Inhale, whereas the series exhibited is titled 'Product Recall: An Index of Innovation'. Could you elaborate on the connection between the two titles?

MJ'Product Recall' is one complete work and the entire series will be shown for the first time in the U.S., where it should be shown since it's dealing with vernacular American consumer history. 'Product Recall' has been shown in many other places around the world, and some parts of it were shown in Front International in Cleveland. The work deals with consumer and food items that either failed or were withdrawn due to health reasons. I'm also looking at the cultural and political underpinnings of why certain things failed or were considered innovative and what that reveals as a kind of cultural anthropology.

Since this is the first time the complete series is being shown in the U.S., I wanted to contextualise it within the contemporary U.S. landscape. The alternative title—I Drank the Kool-Aid But I Didn't Inhale—adds a meta-layer to the project, with metaphors referring to eating, drinking, and ingesting, as well as a reference to Bill Clinton's claim that he smoked marijuana but didn't inhale. Taken together, the title considers this idea of having your cake and eating it too. This idea is paramount right now with the current administration and the promises that were made during the election campaign: we can have the best healthcare, but no taxes; we can have a wall, and not pay for it ... all sorts of stuff. So the title reflects a desire on my part to highlight a certain American expectation of limitless growth without any costs, which has led us to where we are now.

PNMany of your references are particular to American culture, such as the American products in 'Product Recall', which includes the diet pill Ayds and its radically altered insinuations during the AIDS crisis. What sorts of conversations do these references generate in Europe and Brazil, where you have also shown this work?

MJObviously, I did not vote for the current administration, but I want to make it very clear that I'm also trying to look beyond that. The current administration is a symptom—it hasn't come out of nowhere. A lot of the items on view in 'Product Recall' are about consumer culture in the U.S., but that culture is so internationalised now. People easily relate to it, but who doesn't have some kind of relationship to or at least recognition of McDonald's and Coca-Cola? People recognise the arguments and the fault lines these days, particularly within the art context. It's in the media, it's everywhere. It resonates, but my guess is that it will resonate on another level in the U.S.

I would never have picked the ICA title for a European show because 'I Drank the Kool-Aid' is a U.S. colloquialism. Not everybody is going to get it. I think there's a subtle layer. The work translates very well and it travels very well, but within a specific U.S. context, it is more an immediate knowledge.

PNA lot of your works deal with archives and contested history. Your photo installation Independence Day 1934–1975 (2009–ongoing) brings together Independence Day photographs of former European colonies, while the film Staged Archive (2008) integrates national archives into a fictional narrative. Both of these works use archives to generate new associations with authenticated records or histories. In doing so, one could say that you are creating an alternative archive. Could you discuss the role of archives in your practice?

MJThat's a really good question because when people think about archives, they often think of black and white photos in some dusty library. 'Product Recall' focuses on the archive, but it's got this pop element to it. It is an archive of what I would call 'failed pop'. With known brands such as Coca-Cola or McDonald's, recognition is immediate. With 'Product Recall', you recognise the general commercial language in which these consumer items are couched, but you don't recognise the specifics of certain products because they have been relegated to the dustbin of history. The products are both familiar and mysterious.

In the business press there is a stream of literature on why things fail. I read up on some of that literature before making this work. That led me to think about what failures and fissures can tell us about the contemporary consumer landscape or contemporary American capitalism, and in this case, food or everyday consumer products. This work came shortly after Independence Day 1934–1975 (2009–ongoing), an archival research project that deals with photographs of independence day ceremonies in various Asian, African, and Middle Eastern countries. Often people don't see the connection, but 'Product Recall' is an archive in a completely different way—an archive of products that have been relegated to the dustbin of history, but that reveal something about the cultural moment of their time.

In terms of research methodology, I'm not super systematic. A lot of my research involved reading business literature of certain products and talking to people who work in branding or in the food industry, and trying to access certain images or notes that they had during their time. It took a lot of work to contact people, but it was worth it. Someone would mention some product, and then I would start looking for it either in a flea market or eBay, and then that would lead me to other products.

PNWas it easy talking to people involved in the products from the period you are researching in 'Product Recall'?

MJNo, it was not. Otherwise, the project would have been much bigger, but at a certain point, quantity will only get you so far. Adding more volume of information isn't necessarily better. I think the project involves 13 pieces or products right now and that is enough. When you're doing this kind of work and you're relying on the goodwill of others, there's always the need to negotiate access.

My interest is not so much in bringing hidden truths to light, but rather, reframing and recontextualising what people think they already know. That is the question for anyone working with these kinds of research-based methodologies in the 21st century, where the volume of information is increasing at exponential rates. Information is out there if you want it. It's much more a question of what you as an artist do with it, how you show it, and what conversations it generates rather than this kind of WikiLeaks exposé, not that it isn't important.

My aim is not to uncover hidden knowledge. It's there, but the question becomes how to make it relevant—that's my role as an artist. Through framing or juxtaposition, something you might never have heard of might become relevant or tell you something you overlooked. That's very valuable, I find.

PNThere is a levelling of language with the visual in your work, with text given equal importance. Could you talk about the role of text in your work?

MJText is quite prevalent in a lot of my work. For me, it's a personal affinity, as I studied literature. It's not some law that applies to all artists at all, but for me, when I see a photograph, I always need mediating information, such as a caption—especially these days when we are inundated with images. That's where I see my intervention as an artist. One thing to keep in mind about 'Product Recall' is that the text uses different voices and strategies. For example, some of it is a timeline of the product—the developmental stages of the product and what that reveals, when it was launched, why it was launched, who did it, and so on. Text plays different roles within this work depending on each piece. In one case, there is a small piece of text that is the jingle from the product's ad.

There's one product called Ayds, which was a diet candy. It had amphetamines in it, and it was very popular in the fifties, sixties, and seventies. In the eighties, their market dried up overnight with the advent of the AIDS crisis—despite the fact that it was spelled differently and it existed prior to the AIDS crisis—because they had taglines like 'Ayds keeps me slim', and 'Lose weight with the aid of Ayds'. There were other reasons as well. People became more health conscious and questioned what was in the candy, but I think it was mostly the unfortunate naming of the product.

To generate the accompanying text panel for this product, I cut and pasted online conversations on blogs and websites like 'My Favourite Products from the 70s' or 'I Remember the 80s', in which people reminisce about Ayds and talk about either how much they miss it or how it ruined their lives—although most people really miss it because they were overweight and claim it worked really well. I wanted the text to reflect some of that online culture and how people reminisce or exchange information online. The text panel for Ayds is a collage of these online voices. There's no 'analysis', but rather an almost found text. So, even within 'Product Recall', there are shifts. I always mix or shift voices so that some are personal, some informative, and some fictional, while others are more dry and factual, or forensic.

PNI couldn't help but compare 'Product Recall' with 'Generic Corner', which you made for a 2015 solo show at Kunsthalle Basel, where we see an archive of products with white packaging and black text that are, essentially, unbranded. A lot of your work deals with consumer culture, including its psychological repercussions and motives and especially within this context of a global capitalist society. Could you talk more about this work in relation to what you will be showing at the ICA?

MJI'm happy you brought that up because one work often leads to another, and 'Generic Corner' was an example of where it developed very nicely. I was researching a lot of different products for 'Product Recall'. Somebody on a blog called 'I love the 70s' wrote, 'Hey, anyone remember those generic products from the 70s?', and then he had a picture of this black and white beer can. I started researching these products because I vaguely remembered them from the late seventies and early eighties, but not really. I was too young.

Generic products speak to a strange radical moment in the seventies, when there was this concept of an unbranded product, be it beer or peanut butter or cigarettes. There were factories and distributors, but no companies or logo or brand behind them. When I saw those products I immediately knew it was going to be another work—an archive just like 'Product Recall'. There is a nice visual contrast and continuity between 'Product Recall' and Generic Corner. The former is failed pop: it's colourful and bright. In Generic Corner, you have analogous products, but they're unbranded and the packaging is solely black and white.

It's interesting because we are in a time when everything is branded or monetised, including the self. I did this work in 2015, but a lot of the places where these generic products were manufactured were manufacturing centres in the U.S., and a lot of the workers working on them were unionised back then. It was a very strange and interesting moment. The idea was that because you're not paying for marketing or branding, the savings were passed directly onto the consumer. It's antithetical to where we are now, where it's not the product, but the branding that is really the most important thing. Generic products were once stigmatised—if you shopped in the generic aisle, it was a sign of poverty or frugality, but not necessarily in a good way. Now, those products look hip. Text in packaging is so big now. It has come back as a kind of high-end niche marketing for wellness products and organic food.

PNWould you classify yourself as a historian?

MJNo, because I don't think I'm systematic enough—it's a much more ad-hoc approach with a certain flexibility for what might be considered good or bad. Actual historians have a very defined method. In this age of fake news, it's important that you have people who are dedicated to empirically-verified or validated results achieved through different tests and research using a number of sources. That work is important and I have a lot of respect for those that do it. But, the nexus between history and fiction is interesting. One now has to be careful with all these discussions around fake news. If I were to work on this border between history and fiction now, I would keep in mind the current context. If you are thinking historically, you're also thinking contextually. That's important.—[O]