Mattijs Visser

Mattijs Visser is the founder and director of the ZERO Foundation, which was established in 2008 with the support of ZERO’s original members, Heinz Mack, Otto Piene and Gunther Uecker, as well as the support of the Museum Kunstpalast and the city of Düsseldorf. The foundation is an ongoing project that brings together the archives of ZERO artists while continuing the vision of ZERO through expansion of a network founded in 1953 when Otto Piene met Heinz Mack as students at Düsseldorf’s Kunstakadmie.

Prior to this, Visser was Head of Exhibitions at the Museum Kunstpalast from 2001 to 2008, where he organized the International ZERO exhibition in 2006. Visser is the nephew of Henk Peeters, one of the central figures in the international ZERO network, and a co-founder of the Nul group in the Netherlands, this led him into a career he describes as one that exists between the public and the moment of creation. With a background in architecture (Visser studied architecture at Delft University) and an interest in theatre (he co-founded the Toubleyn theatre company in 1986 with Jan Fabre), Visser locates the founding of his career to an article he read about American theatre director Robert Wilson in which Wilson explained how he studied architecture with an idea to make a building in the shape of an apple. When Visser was nineteen, he asked Wilson if he could work with him. Wilson said yes and Visser worked with Wilson for five years before meeting Gianni Colombo and François Morellet and working with them as an assistant. Since then, as Visser recalls, he has always worked to facilitate artist needs.

In this interview, Visser discusses the history of ZERO, his own relationship to the movement, the establishment of the foundation, as well as the recent Guggenheim exhibition ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow 1950s–60s

, which is the conclusion of a three-year research project undertaken by the Guggenheim, Stedelijk, and the ZERO Foundation in Düsseldorf. Visser talks about how the exhibition will travel to the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 2015 (21 March to 8 June and 4 July to 8 November, respectively), and how these exhibitions will differ from the New York iteration.

Could you talk about the exchange that went on among ZERO artists in the sixties, particularly in the Ruhr region and beyond? I understand the car played a huge role in the way artists connected to each other at the time, and I wonder if you could expand on this.

Yes, well to have a car was important to anyone working in the region at the time, because if you had no car, there was no way to show your work! So to buy a car was the first necessity.

Of course, nobody has written about how cars were so important for ZERO! This even helped to decide the format of your painting, so if you look at the early work of Manzoni, for instance, consider how he had a little car at the time: a little Fiat Topolino, a very small car, so he moved around with little works. And what happened was that artists had to get money for petrol and to do that they had to sell work, so they would arrive here in Dusseldorf, for example, and give works to friends so that they could sell them; this is how many works were left here. Many ZERO works were in fact left in the places where they were created, and in some cases in basements. For example, we just found an enormous collection in Fontana’s basement that constitutes an entire ZERO show. Of course, Fontana was a great master, and most of his friends gave work to him, but also, Fontana was a big supporter of his friends and artists in general and he went around buying their work. But these collections have never been shown, as is the case with the collection of Yves Klein. The collection of Heinz Mack was recently presented for the first time here in Dusseldorf at Beck & Eggeling.

Heinz Mack, Siehst Du den Wind, 1962

A lot of these exchanged works were made by artists for artists. You had works that formed a chain: for example, Jef Verheyen, a Belgian artist, a master at using paint—he was better than Fontana—gave Fontana a painting, and Fontana made cuts to it then gave it to another artist, who added a metal piece. Now we have discovered written on the backside of one of these Verheyens painting: “Badly made by myself.” Later the painting was included in a solo show by Fontana: so this tells us a lot about sharing and art and the market when it comes to ZERO. Most of the works were given away. And for me, the most splendid example is one by Yayoi Kusama. After she exhibited Aggregation: One Thousand Boats Show in the exhibition “Nul” in 1965 at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the director wrote to her asking when she’d take her work back, and she responded that she had no money or time to collect the work, so they could throw it away. Of course, the museum never threw it away. The work also came with 999 posters, which featured an image of the boat in the room, but the museum never realized the posters were essential to the installation until we reconstructed it for a recent exhibition at the Museum Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf in 2006. I would say that this is the daily business of the ZERO Foundation: to reconstruct history with the help of the artists and with archive material, including photos, letters and so on.

This leads us to the establishment of the Foundation. Could you talk about how this came about? I understand it was founded in 2008 with the support of ZERO’s three original members, Heinz Mack, Otto Piene and Gunther Uecker?

My uncle, Henk Peeters, was a ZERO artist: he was one of the central Dutch figures who organized all the museum shows for the Zero movement in Holland, so I was raised around ZERO. The idea for the foundation actually began through him, when he told me in 2005 that someone from the Getty institute wanted to buy his archive—which included thousands of exchanges between him and artists including Duchamp and Rothko. I told him not to do it, and then I wrote a letter to Düsseldorf’s local government officer for culture, Hans Georg-Lohe, and told him that it wasn’t a good idea that Getty was buying archives here in Düsseldorf, a city with such an important and rich international history. After I wrote the letter, Getty bought the entire archive of a very famous gallery here in Düsseldorf, Schmela, for something like half a million euro in 2006. I would say the next day the Minister of Culture called me and said we needed to talk. From here, I developed the concept to collect works and archives from a handful of artists, including Mack, Piene and Uecker, which I calculated would represent, at that time, a value of 9 million euro. I presented this concept to the city of Düsseldorf in 2006, which agreed to fund us with 300,000 euros per year over thirty years to build the archive.

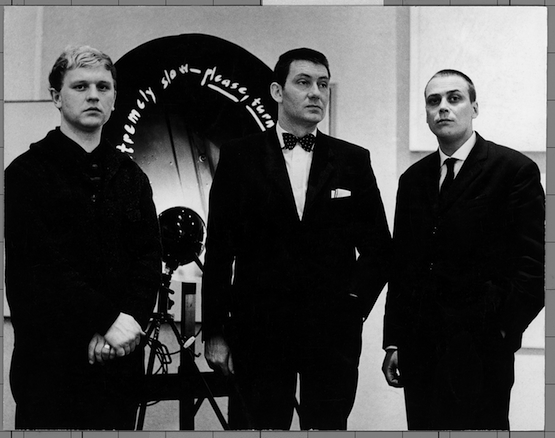

Heinz Mack, Otto Piene, Günther Uecker in Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, 1962

Now, for most of the artists who were at that time still alive, ZERO was past history. But they said from the beginning that it was great that I’d started the archive. In fact, Otto Piene, who I would say was the big master behind ZERO, told me: ZERO is not a movement but an idea and a vision. He was aware that there were other artists with the same vision so he told me to go further and not make something completely historical. He told me to work with younger artists, and to work with science, philosophy, religion and all the other fields that would enter into the ZERO space.

Could you talk about what you described as the divorce between the three original ZERO members, Mack, Piene and Uecker? I ask because the lifespan of ZERO is so specific: 1953 to 1967…

You never talk about divorce! It just happens!

But it’s interesting because the dates are very specific.

Well, yes and no. For Otto Piene, there was no group, no chairman, no movement: it was an idea, so ZERO never stopped. It’s still alive. Yves Klein always used to write: Viva ZERO. So for Piene, there is no end.

And yet there is this definite timeline.

The last ZERO exhibition was staged in 1966, more or less. It was a big party at a railway station with balloons and ZERO lights. From that day on, Piene was in the states, working at MIT, Mack started creating public installations and sculptures and Günther Uecker who loved to travel, went to Asia and parts of the world.

How do you feel the show at the Guggenheim representated ZERO?

What is difficult is that when you make such an exhibition with artists who made such important steps from two dimensions—painting, for instance into space, you need to keep things broad. These artists used land art, conceptual art and minimal art to conquer space with ambitious projects that even included projects for the moon! This idea is so expansive that it was impossible to show this at the Guggenheim given the size of the museum, which meant we were unable to show bigger installations. But this is something we will do when the show travels to Berlin and Amsterdam. We will have many bigger installations that use light and space and music, and we will also place more emphasis on the whole idea of collaboration in the movement.

So in terms of how the exhibition will evolve, the “network” was covered by the Guggenheim while the Berlin show cover the more tactile and typical ZERO aspects: light, shadow, fire, movement, space, vibration, movement. And you know, one thing I noticed in New York was that so many journalists asked who was part of ZERO: this is the first question for the galleries, too. Perhaps it made sense over there to concentrate on who was in ZERO rather than the ideas ZERO explored.

Exhibition view, ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s-60s, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: David Heald

Could you tell us about the highlights of the Berlin and Amsterdam shows, and expand on how these exhibitions differ to the Guggenheim exhibition?

When it comes to Mack and Piene, their first confrontation with a new art was seeing the coloured monochromes by Yves Klein at Gallery Schmela. With the help of Daniel Moqay from the Yves Klein archive, we are very proud to have a room filled with almost thirty colored monochromes. Four of them I discovered myself in a completely forgotten collection, including the first monochrome Klein sold abroad. Further to this, we have so many collaborative works by Verheyen, Goepfert, Fontana, and Manzoni. These really show how close and friendly these artists were. Heinz Mack will reconstruct an enormous installation from the sixties, too, as an homage to his dead friends: a kind of Olafur Eliisason installation avant la lettre.

You were born into ZERO: could you talk about your personal experience of having been shaped by the movement from such a close distance?

Well, I’m not proud of this story, but as a child, I was probably six or seven, I also wanted to be an artist because I loved my uncle so much. So I started a series of works called “improvements.” One of these improvements was an additional cut I made to one of the Fontanas! Another improvement was to a work we had by Pol Bury: a wooden panel with a thousand metal threads coming out and a motor. If you know the sound of metal on metal, it’s horrible, so I demolished this work completely!

But in the end I didn’t want to become an artist—I ended up studying architecture. For me, this reaction I had as a child was an aggression towards my surroundings, and I eventually used that. But I’m not an architect either, or an art historian. I would say I’m more of a facilitator: I locate myself in between the public and the moment of creation and I try to bring these elements together as I bring people together. I try to connect the artist, the public, the museum, the journalists, the curators, directors, and all these different fields together.

Exhibition view, ZERO: Countdown to Tomorrow, 1950s-60s, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: David Heald

This relates to how you ended up founding the ZERO Foundation, which has its roots in the ZERO exhibition you organized in 2006 while serving as Head of Exhibitions at the Museum Kunstpalast.

I started in Museum Kunstpalast as Head of Exhibitions in 2001, and that same year they asked me to make a show with Mack, Piene and Uecker. For me, this was a very serious question because I had never realized that ZERO was Mack, Piene and Uecker since I had always known it as an international network of artists. So I started talking with the three individually since they were not on speaking terms at the time. This actually helped me decide how I would make the show with all of the ZERO artists so as to avoid this discussion with Mack Piene and Uecker about who founded ZERO, since Mack and Piene founded ZERO, for example, and Uecker joined three years later, while Yves Klein said he was a ZERO artist from the beginning as did Manzoni. For this reason I believed it was a good idea to produce an international ZERO show that presented this rich and complex network.

And the discussion about who belongs to ZERO is never concrete, given how expansive the network was and is, right?

As an example, when my uncle was here for the first time in Düsseldorf in 1961 to talk with Mack and Piene, Yves Klein was there. They discussed an idea to make a show with ZERO artists, and Yves Klein told my uncle about the Gutai: what he called artists who worked in the ZERO style. But then eventually, Klein didn’t support the Gutai artists, while my uncle remained fascinated by them, so in 1965 he invited the whole Gutai movement to be in the ZERO exhibition in Amsterdam. For this reason, the archive I have from my uncle includes works and letters from all the Gutai artists. When I made the ZERO exhibition here at the Museum Kunstpalast included, following Peeters and Ueckers advice all the Gutai artists.

Can you expand on this tension between Klein and the Gutai?

Yes, unfortunately. Günther Uecker loves the Gutai artists. But when I started preparing the show it was clear that some artists were against my idea of including the Gutai again and its based on what I would say is a mistake. When Yves Klein arrived in New York for his show, he wanted to meet Duchamp and he was so nervous, in New York showing his work, which didn’t sell and journalists didn’t like it, and he was so frustrated. Journalists came to him and asked him if he was aware of the Gutai: they’d shown at Martha Jackson in New York, which is where Fontana showed and Pollock was sold in this period, and he was so irritated that he went back to his Chelsea hotel and wrote the Chelsea manifesto about this infantile ultra action painters from Japan. He was really furious that they believed that he could have stolen something. Now when my uncle told Yves Klein that he would include Gutai in his ZERO shows in Amsterdam in 1962, Yves Klein stepped out: and so he was not in the 1962 show. In fact, it was only after Yves Klein’s death that my uncle was able to include the Gutai group.

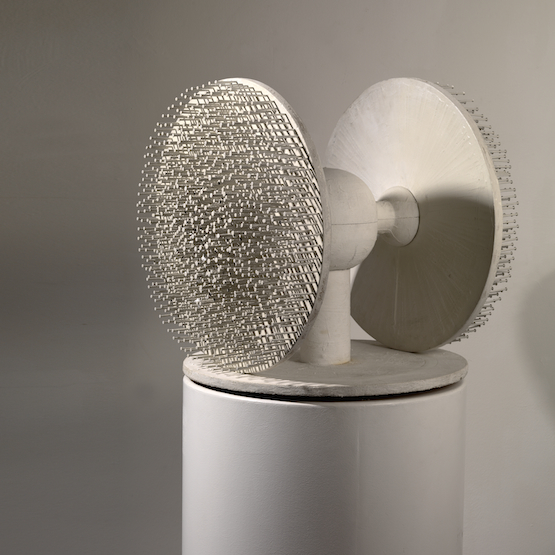

Günther Uecker, Weiße Mühle, 1964

How would you summarise the issues in including Gutai in ZERO?

There is a little problem with Gutai in ZERO and that is the date differences. All the ZERO related works by Gutai were made in the beginning of the 50s; in the 60s, when ZERO was active, Gutai became totally Informel. So I could only include the early works from the '50s in the Kunstpalast exhibition. But then what has been happening is that galleries and museums have started to see these works as predecessors to the ZERO movement, which was definitely not the case, and has resulted in many of my colleagues excluding Gutai again. I think it is great that so many artists all over the world, so shortly after the war, managed to give art a new start, a new space, and a new dimension that was open minded. Geographically and content-wise the movement was without borders; it was the beginning of a new world. —[O]