Meleko Mokgosi's Democratic Intuition

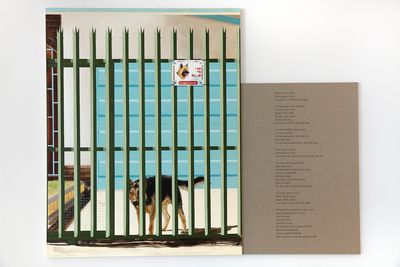

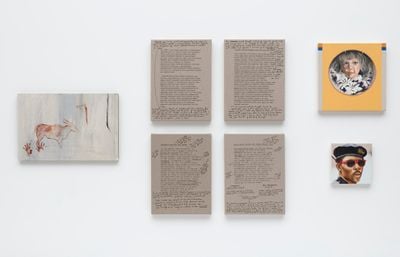

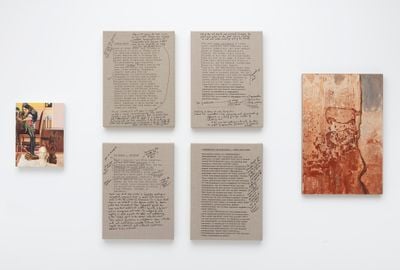

Meleko Mokgosi. Courtesy Gagosian.

Meleko Mokgosi. Courtesy Gagosian.

On the occasion of his first solo exhibition in Europe, Democratic Intuition, at Gagosian in London (29 September–12 December 2020), Meleko Mokgosi describes democracy as incompatible 'with the various systems and institutions that support dominant forms of subjectivity or humanism in general'.

As democratic superpowers yield force through trade, currencies, and a weighted global financial system, economic and political influence not only remain incongruent with the nature of democracy, but also reproduce institutionalised violence. It has been the business of this Botswana-born U.S.-based artist and writer to challenge the structural racism embedded into democratic systems, which his figurations of blackness lay bare.

The ongoing eight-chapter project Democratic Intuition (2013–present) can be read as a response to such conditions: an extraordinary multi-panel epic composed of pulsing depictions of Southern African and Black American life on raw canvas backgrounds, along with confessionary poems, literature, and annotated canvas text.

Building on the techniques of photographic portraiture, there is a cinematic quality to Mokgosi's panoramic view of the world as he sees it. The artist paints people living in rudimentary or lavish homes, furnished with imported material culture and employing a multi-layered framework to report the significance of their communities.

Among the characters that appear are imagined lovers, elderly South African military veterans remembered, and children in uniforms with access to education painted with pride. Annotating their appearance are words by theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, printed on a full panel, espousing the importance of accessible education to a functioning democracy.

A formal mix of the history painting and visual essay genres, Democratic Intuition's visual collages draw associations that move between realism and symbolism, concrete history and overarching narrative. In the panoramic 21-panel chapter Bread, Butter, and Power (2018), for instance, we see two women in the corner engaged in a loving embrace, with the portraits of Harriet Tubman and artist Samuel Fosso as Angela Davis hanging on the wall behind them, alongside a protest poster in ANC colours with a protest call responding to the 1985 Uitenhage Massacre, when South African Police opened fire on a crowd travelling to a funeral: THEY WILL NEVER KILL US ALL.

Conjuring feelings ranging from togetherness, toil, humour, hope, and sadness, Democratic Intuition is an elegant, cohesive, and intellectual statement that distinguishes itself from the established painterly patterns that have sought to represent Black people. Skin is not a jailhouse, refuge, or transient activist realm for Mokgosi, and he works beyond canonised functions that intend to shock or divide in order to summon viewers to reckon with non-sensational images that refuse to simulate Black civil unrest and imagine instead what it feels like to know a community that is united by its cultural efforts to sustain itself.

In this conversation, Mokgosi, who is associate professor at the Yale School of Art, and co-founder and co-director of the Interdisciplinary Art and Theory Program in New York City, reflects on the development of Democratic Intuition within the context of his own evolution as an artist.

EBYou received your bachelor's degree from Williams College in 2007 and participated in the Whitney Museum of American Art's Independent Study program from 2007 to 2008 before receiving your MFA from the Interdisciplinary Studio Program at the University of California Los Angeles in 2011. But you also studied for a brief time at the Slade School of Fine Art, correct? Could you expand on that experience?

MMYes, I had always admired painters such as Lucian Freud, who I heard once taught at the Slade. So because of the rich history of figurative painting, it seemed fitting for me to study there.

However, after applying and being accepted to schools in London, I quickly discovered that I couldn't afford to attend them; but luckily, I ended up getting a full scholarship to study in the U.S.

I did end up getting the chance to attend the Slade during my third year abroad while in college, and it was an amazing opportunity. That year, I also got a travel grant, which allowed me to visit a lot of museums in Holland, France, Scotland, and so forth. That experience was a vital educational moment for me.

EBCould you talk about some of the artist references or influences that feed into your work? You have cited Otto Dix and Max Beckmann as early inspirations, for example.

MMLucian Freud was a key influence for me. But more importantly, I would say that Max Beckmann is a central figure, not just in terms of his technical abilities and how he composed his images—his use of colour, and how he utilised the tryptic format—but also in terms of his role as an educator. He spent a good amount of time teaching in the U.S., much like Käthe Kollwitz, whose work I also admire.

I wanted to make the argument that the studio practice involves different kinds of labour that should be equally valued.

These artists were committed to articulating urgent questions that had to do with class, equality, equity, violence, justice, and other ethical questions. So the space of aesthetics was that of pedagogy, or a space of fostering critical dialogue.

This has always been my approach to making paintings, it is less about the discrete art object, and more about the dialogue and exchange of ideas that is produced by interacting with an aesthetic object.

EBHow would you say that studying in the United States has contributed to your practice?

MMWe are produced by the circumstances that we happen to be around. The American academic system seems to be invested in continental European theory and philosophical models; that's what I was exposed to and what I became invested in.

As a practitioner, I could only have been produced by the system in the U.S., which is Anglo-Eurocentric—though we always try to undo those things.

But I would say that each stage in my development played specific roles. For example, when I studied at the Whitney's Independent Study Program, which had a thoughtful and really clever cohort of artists, curators, and theorists—meeting every week to discuss readings and seminars; there, I was exposed to diverse theoretical and critical models.

My experience there radically expanded my interests in theory and Marxism, which originated from my studies in high school in Botswana. I was already invested in issues of class and labour politics, capitalism in general, the asymmetrical effects and politics of globalisation, and issues of equity and power.

At the Whitney, I had studio visits with incredible and iconic practitioners such Isaac Julien, Mary Kelly, Andrea Fraser, and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, who inspired Democratic Intuition. I did my MFA at UCLA under the mentorship of conceptual artist Mary Kelly, whose practice is heavily influenced by Marxism, psychoanalysis, and feminist theory.

My investment in theory is really about acquiring methods of analysis. It's not just about the process of painting, its theoretical implementations, the different modes of painting; it's also about understanding and investigating the various language systems of painting, installation strategies, and research practices.

So all in all, my understanding of theory is that it is an epistemological tool to understand particular ideas and how they come about. I agree that theory in general has become a catchphrase, and that theory is mostly abstract and hypothetical, but it is also poetic.

More importantly, I gravitate towards critical theory and that which it has influenced, primarily because these are tools that are productive for particular kinds of systems analysis. I am fascinated with how theory examines the manner in which things are made, and at the same time being aware of or reflexive of that very analysis and its effects.

EBAnd this transmits through your positioning of disruptive processes as painting. Historic painting traditions shift and rupture in range as you surround the spectator by the view of enormously sized portraits that occupy, as you've described, as much discursive real estate (space) as possible.

Can you elaborate on how the interdisciplinary art and theory programme you've founded feeds into your approach?

MMThe theory programme began with a friend of mine, Avi, who I met at the Whitney programme, as a way to create a platform that allowed the types of conversations that we felt weren't happening in the spaces we were interested in being a part of.

The art world seems to move at a very fast pace. We wanted to slow down and have particular kinds of conversations about things we care about, at the intersection of politics, representation, history, theory, philosophy, aesthetics, and more. It also allows us to engage with and support younger practitioners, and centre on the questions not being asked and facilitate the kinds of conversations that are not happening in the art world.

EBDoes the offering differ from your work at Yale?

MMMy primary role there is to focus on the discourse of painting and development of an artistic practice. But Yale is an institution with particular expectations of me.

EBYale has a history of producing an admired legion of exhibiting artists. Your work, through studio practice and theory, is forging another institution that spawns a different kind of aim. Could you explain how you define your work? It's discursive, yet engaged, and described as 'project-based'.

MMMy way of describing a project-based practice is a discursive framework—the project emanates from the intersection of multiple frameworks that, as an artist, I am invested in.

The discursive structures that I am interested in, and that intersect in my framework, are Marxism and post-colonial studies; the history and language of painting; critical theory, psychoanalysis, and the theory of cinema, and installation strategies.

The questions that come out from how these intersect is central to what drives the work in the studio. Democratic Intuition is a project within a project-based practice. I must also point out that I learnt about this model from Mary Kelly, who has spoken and written about the idea of a project-based practice.

EBHow does that manifest in your studio practice and its approach to sustaining itself?

MMAs an aspiring Marxist, I try to always ensure that my studio practice does not reproduce the dominant and exploitative relations to production that exist through capitalism. For this reason, I don't have a studio assistant, studio manager, or registrar.

Historiography in the Southern African context is mainly understood from a colonial point of view. So my hope is to find creative ways to supplement this.

Doing this has allowed me to slow down the thinking, reading, researching, and making, which allows me to filter ideas, enabling me to think about the most productive things that I want to say.

Pace is a key element, and I get to develop ideas at a reasonable pace. Aside from this, I also believe that the studio is a private and sacred space, and one that I am unable to share with other people. Even doing studio visits is quite tough.

EBCould you take us through your painting process?

MMYes, and thank you for asking this. I believe the question of technique is a central one, and it carries a significant amount of meaning in any given studio practice. I had to develop a unique method of painting, because during a studio visit at the Whitney programme, someone rightly challenged the whole system of meaning that is attached to the construction of the painted surface.

In 2007, I began by stripping away the various academic techniques that I was accustomed to, beginning with taking away the white gesso as the supposed neutral ground for preparing the canvas surface. In doing so, my argument was and remains thus: that there is nothing neutral about any part in the language of painting.

Deviating from academic painting formulae was one my primary goals. The beige tone of cotton duck canvas became an important ground to construct Black skin tones. In constructing my skin tones, I use a clear ground that allows the texture and colour of the canvas to show through, therefore becoming the highest point of contrast.

Although this technique is effective because the texture and warmth of the canvas is ideal for rendering specific skin tones, one of the side effects of this method is that there is no room for error and over-painting, which can be useful to hide mistakes.

It is virtually impossible to mimic the texture and colour of cotton duck canvas, so once paint is applied on top, there is no turning back. Another interesting development from disavowing the white primer is that paint is removed, rather than added, to create volume.

Since I rely on the beige of the canvas as the lightest point, I cannot use white paint at all to render black skin, otherwise it obstructs the surface of the canvas. So, by building the skin tones using only four colours—raw umber, burnt umber, raw sienna, and burnt sienna—plus the beige canvas, I have strategically gotten rid of using white paint to create highlights.

EBCould you take us through the journey of assembling Democratic Intuition?

MMLike with all my previous projects, Democratic Intuition began with the title, which was adapted from a maxim from Gayatri Spivak. The main premise for beginning with the title is to establish the conceptual framework that grounds the whole project. So before I make any drawings or paintings, it is necessary that I come up with the title and inter-titles, or chapter titles.

This is followed by in-depth research involving data collection—from images to sand samples. The next step involves storyboarding all the paintings that will be produced in each chapter. In the storyboarding phase, I make one 'master' drawing or diagram per painting, and in this drawing, I try to figure out the composition, line work, colour schemes, brush strokes, and the general compositional layout of every frame, as well as how each frame relates to the one next to it.

More importantly, I consider how each frame fits into the installation as a whole. Normally, it takes about a year and a half to two years to complete each chapter.

EBOn the subject of your process, you've adapted fictional texts, museum labels, and annotated footnotes on the body of the canvas. Democratic Intuition has reworked the forms of legendary figures in African-American and African history. The legacy of the late Nelson Mandela is preserved by an immortalised birthday cake, yet it's held unattainably in a glass box.

On the subject of the printed canvas poems, it can take some time for the viewer to register the purpose of digitally driven works that meld and lurk. Could you reflect on the technically enhanced effort of the inkjet-on-linen works?

MMI wanted to make the argument that the studio practice involves different kinds of labour that should be equally valued. The text-based works include poems and museum labels appropriated from various locations.

As part of investigating the politics of representation through figuration, I wanted to do the same with the linguistic text, and more so with the museum label, which as we all know is such a temporary object in the exhibition system, yet it has proven to have lasting power, because to many viewers, this museum didactic is an important frame of reference for how one understands the artwork and makes meaning out of what they are looking at.

In addition to inkjet, I use various printmaking techniques, such as screen printing and image transfer, both of which I explored in more depth when I was at the Rauschenberg Residency several years ago.

I also employ different painting techniques ranging from gestural abstract marks to hyperrealism. So all in all, I try to employ as many tools as I can to address the question of representation.

EBThere are elements where you convey Southern African history. In the first chapter, you respond to the Xhosa cattle killings, which took place in 1856–1857. What is the argument that you are making about Southern African domestic life and labour?

MMI don't frequently use significant historical events in my work. My focus in Bread, Butter, and Power (2018), for example, is on the daily lived experiences of ordinary people, issues of domestic labour, the service industry, agricultural labour, and their relationship with gender and gendering.

There is an argument about the role that the division of labour plays in democratic participation. So there is a way in which we gain self-worth through the social conditions that structure our working life. But to come back to the question of the cattle killings, I wanted to refer to this point of history that produced one of very few millenarian movements in the world, as a way to argue that the movement was a way of 'playing to lose'.

My general approach uses such events and histories to finds ways of opening up and critiquing Western historiography. Historiography in the Southern African context is mainly understood from a colonial point of view. So my hope is to find creative ways to supplement this.

Another event I point to in the installation is the Bambatha Rebellion. That rebellion happened when the government forced the locals to pay an unreasonable amount of taxes. However, Chief Bambatha refused to comply and waged armed opposition. One of the ways the locals rebelled as a small informal gesture of resistance was by killing all the white-coloured animals, which could somewhat be read as symbolic of the white imperialists. Obviously there is more to the story and the history, but I wanted to highlight that gesture.

My practice has never aimed at creating subjects that do not exist—rather, I bring into the representational space people that would ordinarily be left out of these representational spaces.

In terms of the relationship between representation and daily, lived experience, I am interested in the space that the African or Black subject occupies. It has become almost impossible for the Black subject to occupy a representational space where they do not function beyond anything related to race discourse. The representational space that the Black subject is confined to seems to be overdetermined by the politics of Blackness, and my impulse is to say that is unfair.

The African or Black subject should be able to occupy a literal space. This subject should be able to occupy a metaphoric space, metonymic space, historical space, or whatever space they want. Since the representational space that has been created by the Western canon has mainly been structured around race discourse, this subject is primarily confined to those overdetermining structures.

In my work, I use Southern Africa as a case study to examine elements of the daily lived experience of people that occupy these different representational spaces. And perhaps this may explain why most of the scenes in my work are mundane—this is meant to illustrate that we don't have to use an exaggerated gesture or socioeconomic conflict to convey something meaningful.

The subject can exist in a representational space on its own terms—that is important for me.

EBCollective acts of protest, gendered being and nonbeing have become punishable political acts in African settings of recent. Wittingly or unwittingly, your work paints new conceptual tableaus of iconoclasm and idolatry.

By consciously inserting Setswana language into the series without English translation you're confronting cultural erasure and the hopeful restitution of African languages that are not spoken or printed widely.

How does language in your work destabilise the viewer?

MMThe Setswana text I used are short stories that come from an oral tradition; ordinarily, they are not written text. Language is an essential element of how we are structured, and how we understand the world. I wanted to privilege oral history and my mother tongue as a language and history that should be regarded as equally important to the formation of ideas and concepts about the production of systems of knowledge.

I wanted to also highlight that it is okay to have particular forms of knowledge that are not legible to everyone. In this way, the text creates the conditions of de-centring viewers who do not know the language, and therefore points to the asymmetrical nature of globalisation, which always tilts in favour of the Western viewer.

The translation is not included because it was important for a Western audience or viewer to be told this thing is not legible to you. Particular viewers are very accustomed to being at the centre of the world.

EBSome of these characters in your work exist within sexually subversive situations—what is the reasoning behind this?

MMI was not thinking about sexual subversion in this work. However, the first frame of Bread, Butter, and Power does present specific ideas about intimacy.

This chapter is about the various notions of sisterhood, and considers how feminism travels and manifests in different cultural, historical moments, particularly in African or Black communities. That's why Mary Seacole and Harriet Tubman feature in the work. I was trying to present Black feminism within an idealised Pan-African context.

There's an entire community of people captured in this exhibition, from the Black elderly couples in the home, the matriarch serving white families, the mothers, sisters doing each other's hair, the Black children proudly garbed in school uniforms standing shoulder to shoulder with white pupils, as well as the Black girls that uniformly toil in the field while men oversee.

EBWho are these people to you on a personal level?

MMSome of the people I know very well, and others I photographed or I collected their photographs. My practice has never aimed at creating subjects that do not exist—rather, I bring into the representational space people that would ordinarily be left out of these representational spaces. These are specific subjects that, by their being, exist and occupy a place of history.

However, I would say that I never document or reveal any relation I have to any one specific subject in the paintings. Normatively, African artists are always compelled or made to think about their biography.

There is a way in which the autobiography of the othered artist plays into the meaning of the art they make, as if to say that in order for the artwork to be 'authentic', it has to somehow have elements of your otherness reflected in it. You always have to deal with the implications of your biography and the meanings associated with the work you make.

EBHabitually so...

MMAnd it is something I will always resist.—[O]