Mónica de Miranda’s Geography of Affections

Mónica de Miranda. Courtesy the artist.

Mónica de Miranda. Courtesy the artist.

Modernist ruins, dramatic landscapes, immersive sounds, and affective spaces characterise the work of Mónica de Miranda, who describes the scope of her practice as a personal geography of affections.

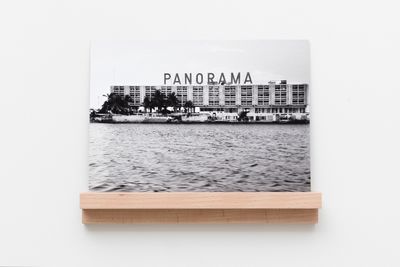

This rich and sensory cartography is anchored to the two contexts that have defined de Miranda's life, Angola and Portugal: sites that function as both backdrop and protagonist in film and photographic installations designed to evoke a multitude of senses. For Panorama, first shown with Tyburn Gallery in London 2017 before showing in Angola with Banco Económico in 2018, the artist photographed abandoned modernist spaces in Luanda including Hotel Globo, Hotel Panorama, and Cinema Karl Marx—buildings that embody complex histories of colonisation, decolonisation, modernisation, and migration.

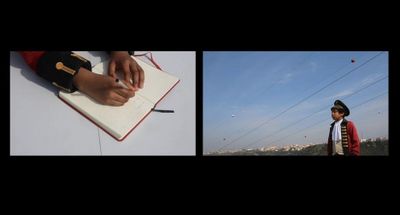

A fluid sense of separation and duality runs through de Miranda's work. As signalled by twins that appear amid Angola's abandoned modernist buildings in the 'Panorama' and 'Twins' photographic series (both 2017), the latter shown as part of Ground Control at the Bildmuseet in Sweden (27 September 2020–11 April 2021), and the coastlines that function as edges of reflection, projection, and being, as in the two-channel film installation, South Circular (2019).

Produced as part of the EDP New Artists Award, held in May 2019 at MAAT – Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology in Lisbon, South Circular tracks a number of characters—from a black Napoleon and urban knight to a single mother listening to news of the Angolan Revolution on the radio—around a fortress by the sea looking towards the city of Lisbon. Serenading the movement, an Angolan opera singer chants 'Humbi Humbi', a hymn to freedom.

South Circular references the old 19th-century military road circling Lisbon, built to defend the city against French and English invasions. For Tales of Lisbon, curated by Bruno Leitão and Sofia Castro at the Municipal Archive of Lisbon (19 February–16 May 2020), de Miranda focused on changes that have occurred along this road since she started documenting its informal and suburban neighbourhoods since 2009.

Described by Leitão as 'an exercise in empathy', Tales of Lisbon marked a donation of 239 images to the Archive. The exhibition featured Estrada Militar (2009), a video of a drive along the old military road with passengers describing policies that have affected and displaced its communities, and the multimedia installation Portuguese House (2019), which includes photographic documentation of demolished houses alongside architectural plans and models created in their memory.

Tales of Lisbon extends from de Miranda's Post-Archive Project, which explores the possibilities of the archive to map affective histories of migrations, African independence movements, decolonisation, the creation of Europe's urban landscapes, and the relationships between them. Iterations of Tales of Lisbon will be shown with New Art Exchange in Nottingham, MuCEM in Marseille, and the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium, in 2021.

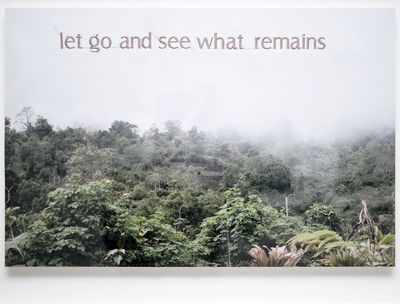

With the artist's solo exhibition at Sabrina Amrani Gallery, All That Burns Melts Into Air, opening this November (28 November 2020–16 January 2021), de Miranda reflects on the concepts that run through her practice, rooted in memories and experiences of what the artist describes as 'a world of dissolving boundaries and disrupted continuities.'

SBYour second solo show with Sabrina Amrani Gallery, All That Burns Melts Into Air, opens soon. Could you describe the show?

MMAll That Burns Melts Into Air is a portrait of a geo-historical reality related to the island of São Tomé off the West coast of Africa; it is an exhibition-installation-film—part-fictional, part-documentary—that tells a story through different chapters composed of plants, sound, video, and photographs.

Instead of 'all that is solid melts into air', the title suggests layers of a new manifestation impressed with an ecological urgency for change. Thinking about melting as a transformative process, the work refers to social and political changes in Africa that occurred during and as a result of liberation movements in the continent's history, including socialism.

The exhibition explores the experience of modernity, its utopias, and its remains as ruins and forgotten memories engraved within the ruins of buildings left abandoned; it is about the simultaneity of destructive and productive forces and its constant process of destruction and renewal.

SBThis exploration of modernity and its architectures extends from your study of abandoned modernist spaces in Angola that feature in the 'Panorama' series. You've said these sites pose questions about beauty in the structure of the city, and how history is embodied by its architecture. Could you elaborate?

MM'Panorama' focuses on the psychic and physical remnants of several pasts—colonial, post-independence, post-Cold War, post-civil war—within the natural, urban, and architectural landscapes of Luanda. The project poses larger questions that are deeply personal and affective, about history, memory, and desire. These ruins exist across Angola, like scars; they are reminders of a past that everyone wants to forget, with all its complexities.

The title of the project, 'Panorama', comes from the name of a well-known, once-prosperous hotel—a modernist building now in ruins situated on Cape Island in Luanda. But the name takes on various meanings.

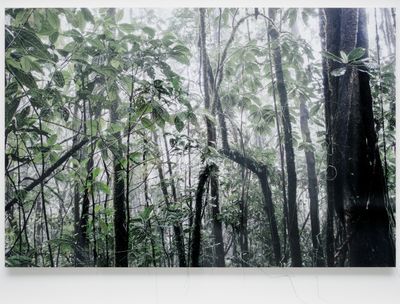

We see visions of the past and present of Angola through its architectural geography: hotels, swimming pools, and cinemas. These mid-century modernist buildings that once served as monuments to colonial leisure are now abandoned, repurposed, and are silently being reclaimed by the lush natural landscape.

The diaspora is as an exemplary case of cultural formation and intense mediation within a world connected through flows and networks...

The urban space bears witness to the country's troubled history of colonisation, decolonisation, civil war, gentrification, and globalisation. In this project, spectators are invited to reflect on the structures of power involved in the construction of an urban landscape, as well as the current social and political panorama evoked by it.

SBIn this sense, the images of Cinema Karl Marx are emblematic. The cinema was built during the colonial era and was inaugurated in November 1961—the year the armed struggle for national liberation began. Prior to independence in 1975, it was called Cinema Avis.

MMCinema Karl Marx was designed by two Portuguese architects, Luís Garcia de Castilho and João Garcia de Castilho, who moved to Angola and participated in the construction of various emblematic buildings there.

The diptych of the twins in the 'Karl Marx' series (2017) combines a documentary record of the cinema's theatre stalls with the marked theatrical presence of two sisters. In the first photograph, the spectator is put in the place of the screen—looking at the public while the public looks at them—in a game of seeing and being seen, echoing the dichotomy of self and other. In the second photograph we are led to observe the room in more detail, in a close-up of the chairs, empty and in a state of disrepair.

Now abandoned, the building is an uncomfortable reminder of the colonial past, the civil war, the decadence of historical and cultural landmarks, and the process of gentrification of which the city has been astage.

SBYou have described a strategy of capturing spectators through an aesthetic that attracts before it hurts; this comes through in the video work Dó (2018), which follows a ballerina navigating concrete spaces. In one sense, that ballerina is a mirror of the modernist buildings in your work, when thinking about ballet as, to reference artist Marwa Arsanios, a European dance that 'modernises' bodies.

MMThe diaspora uses symbols of both Western appropriation and transformation, whether the figure of the ballerina looking into the mirror of Cinema Karl Marx, or the violin orchestra playing the echoes of the past in the video into the present. Identity is now a mix between the past and a jump into the future seeking to construct a space of belonging and for imagined communities.

Here, we could think of a kind of decolonial theatre with its own dramaturgy, characters, social actors, and narratives, in which the dynamics that animated and still animate the relationships that are perpetuated in contemporary times, of the philosophy of aesthetics, are explained. In relation to the city, who questions who we are in this play?

Dramaturgy and representation have been used in many theories of the humanities and art as instruments of analysis and social transformation, such as Augusto Boal's Theatre of the Oppressed, precisely because they powerfully spell out the elements that make up the dynamics of society.

SBIn this light, complexity is fragility, which relates to this sense of negotiation that curator Paula Nascimento locates in the work of diaspora artists as 'artists in transit'—in your case, 'situated in this intermediary space' not only between Portugal and Angola, but 'what is past and what is future.'

MMThe diaspora is as an exemplary case of cultural formation and intense mediation within a world connected through flows and networks, capturing human mobility and (re)settlement not through the frame of opposites, nor as cause and effect, but as co-existing elements.

In relation to the city, who questions who we are in this play?

My work investigates the complex and changing formation of identity through the perspective of the diaspora experience within an interconnected world. More specifically, it looks at the significance of mobility, immediate and mediated intersections, and juxtapositions of difference as necessary elements in the analysis of current formations of identity.

SBThis analysis of identity formation comes through in South Circular, a two-channel video installation exploring themes of African connection and belonging in Europe.

MMSouth Circular is an outcome of many years of research that archaeologically investigates the urban reality of Lisbon and its African neighbourhoods. These places stand as points of resistance in the city, which reclaim an African ownership to belong to Europe.

While All That Burns Melts Into Air reflects on the ruins left by the Portuguese in Africa, South Circular is related to the contemporary ruins of illegally built neighbourhoods in Europe and the reclaiming of belonging to a city that excludes foreigners from its centre.

South Circular signals an old military road that was built in the 19th century to defend the city against French and English invasions and now holds all African neighbourhoods. This road circumnavigates the capital, but never enters it. In this redeemed geography, duality is the constant.

In the film, we see twins going down different paths within the same road, a black Napoleon, two men discussing what Europe is, and a single mother who is a mix between an urban warrior and a liberation fighter who keeps building a home for herself, while listening to news of the Angolan Revolution on the radio.

These characters and narratives are all metaphors for time and space opposed, since past and present constantly intersect in the experience of the diaspora. Once epic ruins are abandoned, a new urban landscape is born and cemented, but now exists separately from its surroundings and has an identity of its own, alien to any notion of belonging to the city.

In turn, the city resists including this new landscape, obeying an inherited logic of Europe as a territory where all that is different or in any way not clear-cut is segregated. This is also the metaphor for Portuguese House and Panorama.

SBPortuguese House is a multimedia installation that featured in Tales of Lisbon, a show at the Municipal Archive of Lisbon that recently marked a donation to the Archive of 239 images documenting informal neighbourhoods on the former military road in Lisbon.

Could you talk about the images you showed in this exhibition? You also presented the video Estrada Militar (2009), which is a moving map of the old military road itself.

MMWhen I arrived in Lisbon in 2009, I found a hidden city that is not featured on postcards. That year, I started a collaborative project with Paul Goodwin titled Underconstruction, which deployed contemporary art strategies—photography, installation, socially engaged collaborations—and urban theory to map the complex relationship between Lisbon's shanty towns and city centre.

The video Estrada Militar was created as part of that project: it traces, as in an archaeological quest, the landscape of Lisbon's old military road. This road is kind of a fortress, and has partially disappeared—what remains is social housing neighbourhoods and ghettos. In that sense, the road somehow remains a fortress protecting the city against foreign invasions; it holds a large immigrant population from entering.

For the last ten years, through a process of collaboration with housing associations and inhabitants of these neighbourhoods and with friends and my own relatives, I have been documenting the changes that have been occurring within these sites. I have seen entire neighbourhoods demolished.

These characters and narratives are all metaphors for time and space opposed, since past and present constantly intersect in the experience of the diaspora.

The photographs are documentary: they were part of an archive that I was building about a city that was disappearing without realising it. After some years I understood that this city I photographed had completely gone, and I also understood that these images did not really belong to me. That was when I decided to donate them to the Municipal Archive of Lisbon.

When the Archive invited me to exhibit these images, I proposed to create a new work based on them instead, which is how Tales Of Lisbon developed into an installation of photography, video, and sound portraying the houses along the military road that are being demolished.

SBPart of this installation was Portuguese House, which is composed of a video, photographs, and MDF models of houses, correct?

MMPortuguese House consists of photographic documentation of houses that have been demolished, shown alongside architectural plans and models that were created afterwards as an act of recognition of the right to safe housing. Though architecture can be considered a privilege or a right, it cannot be denied that the right for shelter does not wait for suitable building conditions.

My work investigates the concept of the house as a container of memory, time, and history. These places are intersections between larger stories and contain histories of migration, colonisation, and decolonisation.

In the installation, an orderly set of photographs portray used objects that were collected in the vicinity of demolished houses from around the military road: a VHS cassette with the title 'Deadly Weapon', an audio cassette split with slat marks, a dictionary without a cover that begins on page 95 that seems to be torn away, school notes from a course on the political economy from the University of Lisbon highlighted with diverse colours.

The work became a meta-narrative. Angolan writers were invited to imagine stories around these objects, creating a universe of projected African memories within Lisbon homes. In this sense, the Portuguese house recalls the Angolan house.

SBTales of Lisbon extends from the Post-Archive Project, which connects to your research into migrations, African independence movements, decolonisation, the creation of Europe's urban landscapes, and the relationships between them. Could you elaborate?

MMPost-Archive is a practice-based research Project that analyses, in a comparative manner, the transcultural and migration movements in Europe, and examines how nationality and transnationality shape day-to-day experiences of place and culture.

The project takes the form of a contemporary art archive, combining factual past and present contemporary experiences with history and memory, intertwined with fictional re-imaginings of post-colonial urban places and spaces through the place of the familiar, the genealogy, and the personal.

These archives are presented as a web-based platform.1 It is a study and practice of storing, cataloguing, and retrieving documents, photographs, videos, and postcards related to the city and the present post-colonial geographies of Lisbon in Portugal, Luanda in Angola, and Praia in Cape Verde and their contested territories, legacies, memories, and identities.

Post-Archive also looks to the artist as an archaeologist and ethnographer, who works as a personal archivist and ethnographer of histories; and who aims to recover and reconstruct memories and archives in order to reveal how this process of archiving shapes a relation to the past and to the construction of historical meanings for a present understanding of urban realities. As part of this project, Tales of Lisbon intends to find a way of archiving that isn't static, but that captures something in mutation.

SBHow will you approach the iterations of Tales of Lisbon that you will stage with New Art Exchange in Nottingham, MuCEM in Marseille, and the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium, in 2021?

MMAt New Art Exchange I will be working around my project Black Tales, which is related to Tales of Lisbon but reframed by the new locality of Nottingham. We are reflecting on radical pedagogies to build an exhibition that becomes a site for new encounters, engagements, and creations.

I intend to work mainly with sound. The idea is to build a recording studio in the gallery space to work as an archival device that collects stories and then presents those within the same space.

When I create two-dimensional works, I try to create a space that goes beyond the image itself in order to open other dimensions of perception.

SBOn the subject of sound, which features strongly in your work, I was particularly struck by the rich mesh of choral voice and ambient sound in In(sul)ar (2019).

MMI have been working in collaboration with the Cape Verdean musician, sound designer, and rapper Chullage since 2017. Chullage has been composing the sounds of my films, having as a base the life sounds I capture during the filming process, then all the layers and soundscape are orchestrated from there.

My interest is in bridging and muddling the barriers between sound, noise, and music in the contemporary or historical sense—to investigate the political and cultural implications of certain sounds that are used to convey another layer of thought that the image cannot reach. As I want to recall memories from ruins, sound can give the impression of whispers from the past.

I also want to engage with the spectator on a deeper level, and sound can affect emotions and activate psychological responses immediately, without any thought or explanation. It can create a sensory experience and another level of communication that goes further than any visual reception of the work.

SBWhat is also striking is how images become objects in your work—as is the case in 'Archipelago', with the landscape photograph Lost Paradise (2014) composed of four scrolls supported on an easel, or the 'Linetrap' series (2014), in which images are sewn into. Likewise, exhibitions are approached like installations or assemblages; a screening is treated sculpturally.

MMMy background is in sculpture, so I am interested in the experience of space. When I create two-dimensional works, I try to create a space that goes beyond the image itself in order to open other dimensions of perception.

I am interested in creating photography as a three-dimensional experience; in installations as experiences, rather than visual encounters, which expand the perception of the image. The space of the exhibition becomes a choreography of experience through display, where narrative, spatial, or temporal order seems to escape. I try to build installations that call for an aesthetics of communication. Works are displayed as multiple panels, fragmented.

For 'Linetrap', I sewed lines into the works to undo a fixed landscape, crossing the interior and exterior of the image to do so. Sewing is an activity usually associated with the private world, but in the context of this work it touches, almost prods, the public versus private dichotomy.

Moving between the interior and exterior, these lines do not divide, but mend the rifts between coloniser and colonised, between the present island and the past, like a lost archipelago that we have to fix and mend.

The idea is to understand the landscape not as something built, but as something buildable; not as a reflection of determined political imagery, but as the space for potential action. I am interested in a practice of environmental awareness and emotional geography.

SBThat concept of 'emotional geography' recalls the title of your PhD, Geography Of Affections: Tales Of Identity. You have said this 'geography of affections' developed after a shift that happened through your 'Once Upon a Time' series. Could you talk about that?

MM'Once Upon a Time' definitely marked a shift. The project describes a personal tale of my own diaspora experience, which crosses the boundaries of nation-states and is located between different geographical places. But actually, the shift occurred when I moved to Lisbon after 15 years living abroad in London, where I did my PhD. I was lucky enough to have artists such as Keith Piper, Sonia Boyce, Roshini Kempadoo, and Jon Bird as my supervisors.

After returning to Portugal, I started going to Angola to reclaim my ancestral roots and my work shifted again because the place, time, and space of where I was relocating also shifted. I was no longer a migrant but was returning home; a home outside my home—I was kind of a stranger to myself and did not feel entirely Portuguese or Angolan.

It was in the duality where I built my sense of self. I started to connect with my African ancestry and relocated to Angola, where I have been working since 2010. This life shift signalled an inquiry into what I call my own 'geography of affections'. This geography is defined as a place of bounds and personal emotional relationships; a place to search biographical processes that shape my own identity.

I am interested in creating photography as a three-dimensional experience; in installations as experiences, rather than visual encounters, which expand the perception of the image.

My work recreates histories and places of belonging through a narrative of displacement and affections. This is the shift where my work became an emotional field, 'an imagined geography' where I can express what I am, where I come from, and what I can become.

For 'Once Upon a Time', I started to perform affective archaeologies and cartographies in shifting zones of contact and border-crossing: ports, airports, roads, ships, oceans, islands, archipelagos, cities, buildings, hotel rooms. Identity here is a process of research and inquiry that acknowledges places, memories, affections, and roots.

SBHow does this approach to geography connect to your interrogation of the technologies of power that are historically embedded into the panoramic, landscape view?

MMTake the island images from the 'Archipelago' series: panoramas are fragmented into rows of framed sections, while in other cases you have figures that intervene in the landscape image. Fragmentation is explored in the sense of estrangement from the whole—a very modern feeling that expresses the tragic dilemma of a person who is only capable of knowing themselves by dissecting, dividing, and framing their own nature.

Landscapes always mirrored a male power structure that set vertical and horizontal coordinates on a map according to a dichotomist logic from which all values were derived. My landscapes are feminine and private; where dichotomies are rendered whole. When I represent the landscape, I show it more as a text to decipher, to approach. These landscapes are points of cultural exchange due to their indefinability, revealing limitations of understanding.

In this way, the 'Archipelago' project proposes a trip through a body that's not always visible. Read as a metaphor for a journey into the individual, the island deconstructs the traditional paradigm, and deconstructs identity as fixed with an irreversible origin.

The landscape itself is not fixed, but the result of the movement of bodies and journeys. There is no final scene in this sense, but a continuous process of reinvention, where different fragments, memories, times, and cultures are constantly added. Here, we see that islands can serve as bridges, miscegenation laboratories, and borders and centres of empires—or finally, as models of relational practices and alternative modes of globalisation.

SBOn that note, I wanted to quote your point about 'political responsibility that extends beyond the artistic territory', which you said 'is too much of a burden which could jeopardise the artist's creativity and freedom.' So how would you respond to people who might categorise your work as 'political'?

MMTalking from my own biographical position is a political act without being dogmatic. I am not using art to serve a political function. I talk about reality from my own personal space.

In my practice, other places and other stories are vessels for my own experience—they work like mirrors for my own self-understanding. Art should be the revolution itself, and not a tool for the revolution. We can only talk from a place we know.—[O]

1 For more information on The Post-Archive Project, see here: https://postarchive.org/arquivo/