Nairy Baghramian: Ambivalent Abstraction

In Partnership with The Museum of Modern Art, New York

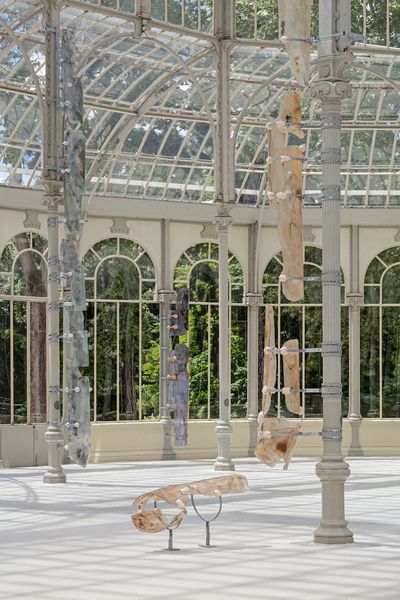

Nairy Baghramian. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery.Photo: Tucker Bair / Clark Art Institute.

Nairy Baghramian. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery.Photo: Tucker Bair / Clark Art Institute.

Over a career that spans two decades, Nairy Baghramian has worked across a range of media but primarily focuses on sculpture. Her work can be described as abstract, although it is an abstraction of reality, and specifically the human body, whose forms it consistently evokes.

When looking at Baghramian's sculptures in their totalities, they always engage the environment in which they are sited—sometimes parasitically, by latching on to a wall or a floor, sometimes generatively, like a foreign growth emerging from the landscape. For Ground/work, an upcoming exhibition organised by the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, with guest curators Molly Epstein and Abigail Ross Goodman, Baghramian's newly commissioned sculpture, Knee and Elbow (2020), explores two parts of the body that carry the weight of the pose as it is rendered in sculpture and painting. By singling them out, the joints are liberated from their function and rendered as abstract entities, void of any physical burden.

Baghramian's sculptures not only resemble bodies, however—they also behave like bodies. Their individual elements work together like anatomical systems—propping up, supporting, and sustaining each other. __

The Iron Table (2002), presented in Kassel at documenta 14 (10 June–17 September 2017) and revisited in a separate sculpture for the Athens iteration of the exhibition (8 April–16 July 2017), interprets Jane Bowles' short story The Iron Table (1943). An unidentified couple sit either side of an iron table that has been dragged over for their use by a waiter, acting as a prop to a strained argument about sudden changes to their plans to travel to the desert. The artist translates this evocative scene into a skeletal structure made up of separate parts containing a red, heart-like lozenge of red.

Equally important to Baghramian is her relationship to the work of others. She is an explorer with an interest for uncovering hidden histories, giving them her attention, and bringing them to ours. In its most straightforward, the product of her interests can take the form of collaborative projects and exhibitions. In one dialogue, Baghramian worked with fellow sculptor Phyllida Barlow to explore the politics of form at Serpentine Gallery in London (8 May–13 June 2010).

Often, however, Baghramian allows her work to serve as a presentation platform for that which she admires—a gesture that highlights the generosity that pervades her entire practice. For a recent show at Marian Goodman Gallery in New York, Baghramian showcased the work of designer, artist, and political activist Janette Laverrière, continuing a collaboration that began years prior to Laverrière's death in 2011, to explore the many possibilities and contradictions surrounding object-making (Work Desk for an Ambassador's Wife, 7 November–20 December 2019).

On 15 July 2020, Baghramian discussed her work with Paulina Pobocha, a curator at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, as part of MoMA's 'Drop in with Artists' series on Instagram Live, touching on the potency of abstraction, the allure of impermanence, and new directions in the presentation of the Museum's collection. Maintainters A (2018), a sculpture by Baghramian made of pigmented wax over styrofoam, cast aluminium, and painted aluminium clamp with cork, is held in the MoMA collection and is currently installed in the second-floor Contemporary Galleries.

Pobocha spoke from her apartment in Brooklyn, New York, where she had been working since the Covid-19 quarantine began in mid-March, to Baghramian, who had just returned to her Berlin apartment from her studio nearby. The exchange below is an expanded and edited version of their conversation.

PPI know we've been chatting throughout this quarantine time, but how have you been? You're in Germany, and that's a country that's handled the pandemic with enviable competency. I would love to hear a little bit about your experience of the last four months.

NBTrue, looking around the world I can only think of my privileged position. I have a safe place to live, I can continue working in my studio, and I can rely on my health insurance. Health insurance is guaranteed and education is free in this country—two social instruments that are still in the hands of the government and have not been given over to the free market. People here know that if something happens, they have access to the healthcare system, which is also under economic pressure and there is a risk of a two-tier society, but the structure that has grown is still so stable that the pandemic has so far not overwhelmed it.

In every decade, there are only a few representative artists who have or who take on the task of cleaning up history, and at some point, they collapse under the burden.

I also felt that both the opposition and the government were level-headed, and above all acted in solidarity and worked together. It was important to experience how political calculus or power struggles by individuals suddenly seemed obsolete. This also led to the weakening of the populist party in Germany, which was on the upswing before Covid-19, and strengthened the trust in the main democratic parties again.

Basically, despite all the drama and cruelty, this crisis also seems to have the potential to reveal truths that have recently become increasingly difficult to recognise due to the deliberate spreading of lies and misinformation. Germany also has national news organisations that in recent history have been reliable—not as polarising or sensational as in the U.S. The maintenance of a reasonably functioning welfare state has also proven to be important, as it is now possible to use the instrument of the so-called 'Kurzarbeitergeld', which guarantees a percentage of wages for employees of struggling companies to be paid by the government, at least temporarily preserving hundreds of thousands of jobs and bridging the situation.

There is only one thing I would complain about, which is the use of language and the fact that in 2020, we are not able to find other words to describe social distancing, such as 'careful closeness', which would mean the same thing but would have a different effect, rather than the ultimate goal being to protect just yourself. Isolation follows from social distancing, and what's lost in the equation is that the world is interconnected—it is a whole. This idea of 'wholeness' so crucial to a healthy social fabric is lost.

If I close my eyes, I would really think I am living in the past. The whole idea of being happy at home reminds me too much of the fifties. A safe home doesn't mean the same for everyone. In the end, a lot of women will be forced to stay home, and following predicted numbers, many women are going to lose their jobs.

PPI have a small child, so working from home hasn't been easy, and I consider myself lucky as someone who has been able to work from home, because of course there are a lot of frontline workers who do not have that luxury. As difficult as it is, people have to go to work.

What you say about language and social distancing seems to precisely diagnose part of the larger problem. I've heard a lot of criticism of this as well, because it's not social distancing, it's physical distancing. At the start of the stay-at-home orders, you were working at a women's shelter in Berlin, is that right? That sounds like the opposite of social distancing!

NBAt the beginning of the shutdown I was asked by my former colleagues at the women's shelter to support them, as there have been more women and children in need of protection after rising numbers of domestic violence, and some of the workers are at-risk and couldn't come to work. To me, it felt like a continuation of the work that I've been doing for many, many years as a social worker in parallel to my artistic practice, and I was happy to be able to help them out.

When lost in public space, sculptures raise certain questions around notions such as scale, permanence, size, heroism, history, duration, gender, verticality—all of these notions irritate and bother me, and I need to be bothered.

Going back to the studio to work on my own projects after things at the women's shelter settled down was a relief, yet I remained aware of the fact that there is a bigger world beyond my own studio and city. Right now, I'm working on an edition for the 30th anniversary of the magazine, Texte zur Kunst, and I'm finishing the sculpture Knee and Elbow for a group exhibition at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown called Ground/work, organised by the Clark Art Institute with guest curators Molly Epstein and Abigail Ross Goodman.

PPSo Knee and Elbow was made specifically at the behest of the Clark Art Institute; will it be installed there for a period of time?

NBWhat I think is special about the invitation to the project at the Clark Art Institute is that it was the curators' intention to intervene gently into the landscape, which is used mostly by the residents of the city. As I understand it, the aim is not to create a dense sculpture park; rather, the works should be able to 'breathe', allowing a dialogue between the works without being too intrusive. Normally, the only sculptural intervention in the outside space is a pavilion by Thomas Schütte on the hills near the Institute—a wooden pavilion covered with zinc-plated copper. During my two site visits, it was nice to observe the cows strolling around and licking the zinced sheaths.

The invitation led me to question the burden associated with the pose of the body in sculpture, and how the release of two carrying joints, the Knee and Elbow, could allow some kind of contemplation of this burden. The sculptures will be there for the duration of the exhibition, which will last for a year. It was scheduled to open at the end of June, but it has been postponed to September due to the pandemic.

PPI know from seeing Thomas's pavilion there that the grounds are beautiful. I was surprised that there was only the one outdoor sculpture, because it is such an incredible terrain. You must have made a site visit there before you developed the work; how has it been since, working remotely?

NBI visited the museum twice, and on both occasions I wandered for hours around the park to understand the indoor and outdoor sites, spending a good amount of time with the artworks in the collection. My attention was mostly driven towards bodily poses in paintings and sculptures. What parts of the body hold, or carry a pose? This is a question that has followed me for a long time. I started to think of my sculpture Knee and Elbow as two heavy marble blocks sited next to each other, and I had the feeling that the two joints looked as if they were buried in the plinth by their own weight. I continued to reduce the sculpture's volume and took the body out of the two sculptures, to remove the embedded 'plinth'. The site visits really helped me to reach the final conclusion.

The Knee and Elbow are formations, made out of roughly chiselled marble and cast and polished stainless steel. In trying to transfer the figurative act into abstraction, I was thinking about the joints as prostheses to trying to understand the inner core of the sculpture.

PPIt's interesting what you say about taking the body out of the sculpture; this is something you and I have talked about in relation to a new relevance of abstract forms in this particular historical moment. And for many reasons, I think a lot of this has to do with being in quarantine. Here in New York, it's been a very long quarantine of four months, and my actual visual landscape has changed very little. All of the images that I've seen have been coming through some sort of screen, whether it's Instagram, social media, Zoom meetings, television, the news... In fact, I feel like I've seen more digital images in the last four months than I have ever.

This has made me think about images and image-making, and how abstraction figures into this equation. At times, abstraction is thought of as a retreat from the world, or conversely, as a vehicle for transcendence, and I'm interested in abstraction's capacity to instead represent the unrepresentable, and still be very much part of the world and engage in the politics of a given moment. I think maybe this is by virtue of its resistance to giving over a figure for visual consumption. It's worthwhile to think about that in relation to your work, which has so much to do with the body and has so many references to the body, but is ultimately abstract.

NBYou're absolutely right, if you bring up the idea of abstraction in my work. It is difficult to assign more political potential to one medium or technique over another. This is also the case with abstraction, and I am convinced that it has the potential to convey a political stance without being too explicit or even superficial. For example, the abstract works of Julie Mehretu and Michaela Eichwald come to mind spontaneously, both of which contain a political dimension for me. Julie Mehretu succeeds in breaking the barrier between high and low culture, while Michaela Eichwald is concerned with the critical and almost angry processing, or rather digesting, of bourgeois saturation.

'Ambivalent abstraction' might be a better way to describe my work.

In other words, I think I have an ambivalent relation to any genre, and I don't believe that a single genre has the potential to be political. 'Ambivalent abstraction' might be a better way to describe my work. For me, the entrance to the idea of abstraction, figuration, conceptual art, or minimal art happened when I was very young, in the late eighties and early nineties. With the rejection of certain genres at that time, I felt I should be responsible for dealing with identity politics and postcolonial studies. There was something about it that was disturbing to me.

Digging through art history as a young artist, I had the impression that certain art genres were always assigned to specific groups of people. At that time, I became aware that postcolonial art or identity politics were expected from me, because of my biography as a woman and as a political refugee from Iran. At the very beginning of my work, I had several invitations to participate in exhibitions that were related to these discourses, where I would have been labelled as a young Iranian refugee female artist, whilst I never read anything in relation to, for example, Georg Baselitz, being described as an old East German heterosexual white male artist.

It was my first political act to oppose this temptation and classification, and not take on the obvious expected function. I do not believe that a certain group should fulfil the social mandate to relieve society by taking responsibility for history, or to act on behalf of it. In every decade, there are only a few representative artists who have or who take on the task of cleaning up history, and at some point, they collapse under the burden. This burden should be borne by everyone equally, otherwise we will continue to maintain and establish colonial structures by creating more categories. History concerns us all and belongs to all of us. I was happy to be able to move between different genres and to establish relationships with different genres in order to create an ambivalence.

One of the earlier reasons behind this ambivalence was triggered not at university, but in school. I was at a German school. Periodically, a Holocaust survivor would visit to discuss the unimaginable and inhuman terror of the Nazis. But in all these years, I never witnessed a German Nazi or the relative of someone who was collaborative with the Nazi regime come in to discuss their history with us. That part of the history—the confrontation with the perpetrator—was missing. That unbalanced experience brought me to the troubled and complex thing that is abstraction, and for me, ambivalent abstraction is a collection of problems. For that reason, I don't think of abstraction as a place of retreat.

PPThat becomes so clear when looking at your work. Maintainers A (2018) is made out of wax and aluminium. The sculpture literally comes in pieces, and they balance each other and hold each other up, so there's a transactional exchange between these elements. And as much as they're holding each other up, they're also wearing at each other. In particular, the aluminium is wearing at the wax, and over time, that will continue. So an active and reciprocal relationship exists between these elements.

This brings me to the question of your large-scale outdoor works. We've talked about the Clark, but you also presented an outdoor work for Skulptur Projekte Münster in 2017, titled Privileged Points (2017). To me, it looks like entrails—almost as if the building had been gutted. But I know from what I've read, and from what I know of your work, you're also interested in the history of that site, and the history of other sculptures that have been sited there. In 1987, Richard Serra erected a sculpture in this same courtyard called Trunk, which was later moved to another museum in Germany because the residents of the town requested its removal.

What's not immediately clear looking at your sculpture is that it wasn't in fact completed. Even though it was made for that site, you didn't complete the painting and the welding of the sculpture, knowing that the work wouldn't be there permanently—am I right in thinking that?

NBSculpture in public space is always a challenge, since it is not a self-chosen decision on behalf of the viewer to look at it, as is the case in a museum. The complications that can arise out of this unconscious experience, and the questions regarding how to take up this debate, have been the starting point for the Skulptur Projekte Münster, which, since 1977, happens every ten years. I've participated twice so far with two fundamentally different sculptures. They focused on topics such as the monument versus the anti-monument, privileged spaces, the centre versus the periphery, and so on.

The first time, I chose a peripheral site at a parking lot, and the second time, I asked for a prestigious site, because the work was dealing with the privileged, permanent position of sculpture, and the very representative idea of the site, usually offered to a monument or a statue or memorial. Richard Serra's sculpture was made to stay on the site, and since the Skulptur Projekte Münster is by definition temporary as a project, I wondered whether an artist believes that whatever we make, even if it's site-specific, should stay forever.

The whole idea of occupying a site and how representative that permanent idea can become—that was what I was questioning. The questions I had were not only directed to others, but also to sculpture itself. Privileged Points is an overpainted sculpture made out of bronze—a material that is representative of public sculpture, historically. To keep Privileged Points in a state of temporality was to address that question: what is sculpture? What is the burden of sculpture? What is the power of a sculpture occupying a site? Those are all problems that I've had with sculpture and that keeps me doing sculpture—all those troubled questions are embedded in it.

Curatorial work right now is very similar to artistic practice, at least if I compare it to my own practice, in that it's experimental, process-driven, and not so linear.

Going back to the problem of abstraction as a retreat, a German journalist described the piece as being an abstract, useless, and boring thing that should disappear, and it almost sounded like I should disappear. Whatever criticism arises, I take it seriously, but in this case, I had my doubts. In the end, Privileged Points didn't find a spot in Germany. It went into SFMOMA's collection and is currently shown on the same site as a previous work by Dan Graham. It includes the traces of the previous work and it makes space for something else while reminding us of what was there before. The work has also travelled to the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden of the Walker Art Center and to Mudam Luxembourg.

PPRegardless of intent, what history has shown is that sculpture is mobile. Permanence is not at all guaranteed; your work acknowledges that and works it into the subject matter.

NBCorrect. Although as an artist I do confront myself by looking at monuments and memorials. When lost in public space, sculptures raise certain questions around notions such as scale, permanence, size, heroism, history, duration, gender, verticality—all of these notions irritate and bother me, and I need to be bothered. Of course, this also depends on the individual case, and each must be examined for its individual meaning. I think it is important to differentiate between a statue, a monument, a memorial, or a sculpture. It is a complex question, but I have a hard time trying to detach myself from the problematic past. It's important to draw attention to mistakes. Coming back to the mobile aspect of sculpture—in my case, my sculpture is aware of its performative aspects and potentials; it is able to move and make space, and so on.

Now I would like to ask you a question, so as not to finish the conversation with the artist's voice. Looking at the new hanging of the collection at MoMA, I was quite positively surprised. Curatorial work right now is very similar to artistic practice, at least if I compare it to my own practice, in that it's experimental, process-driven, and not so linear. All these questions that are important to creative work are also at this time part of curatorial decision-making. You didn't give up the linear history, but you shook it up, so there is no misunderstanding of history; rather, you created a whole reading of history that is very much horizontal. How did it feel for you? Are you afraid of making any failures in these weird times, as we should be allowed to do?

PPYes. Of course, there is a huge fear of failure. To go back to your earlier point about horizontal history, I think it boils down to an acceptance of impermanence. For a very long time, not only at MoMA but at museums across the United States, in my experience at least, there was a notion or promise of permanence, especially when considering the presentation of a collection.

I've been at the Museum for 12 years, so I've seen a lot of changes during that time, and I think as far back as ten years ago, the issue of permanence began to be questioned. First, incrementally, we would reinstall one gallery or a suite of galleries—changing the art on view, and with time such changes became more and more frequent. When it came to reimagining the installation of the collection on the occasion of the Museum's 2019 expansion—first of all it wasn't only me, it was a huge team of curators working across all departments collaboratively—I think we internalised the idea that what we did would not be permanent, and, speaking for myself, that allowed me the freedom to think more broadly about how different histories can be told.

Failure isn't a goal, but if something isn't successful, it's not there forever—it's going to change, and I think that gives you more latitude and opens up your imagination as to what is possible. I hope that our audiences were able to register this in the first iteration of the presentation. That's how we will continue in the future—we're going to take objects that are beloved by our public and sometimes present them in contexts that are familiar and other times in contexts that are new, and I think that there's room for both. Especially when you think about space, not only in physical terms but also durational: things happen over time.

NBIt was an amazing experience to go through the exhibition. I was discussing the first iteration with art historians, artists, and journalists and there was an irritation in the discussion about the canon, and the fact that it triggered confusion and problems and questions meant that it's already a success. Curating should not only be representational—it should also raise questions and create doubts.

PPA quick way of summing it up—speaking for myself and not the institution—is that I'm really interested in creating galleries that are a series of propositions, rather than resolutions. Especially when working with art that has been made two or three years ago—I can't know everything, but I can ask a lot of questions.

NBIt's very similar to how artists approach artistic practice.

PPThat's the highest compliment. I certainly don't think of myself as an artist, and of course of most importance to me is to represent the art in the way that the artists would want, rather than to instrumentalise it.

NBYou succeeded!

PPI'm glad to hear it Nairy, and I can't wait for you to come back or for me to come back to Berlin, I think we saw each other in February, right before all this.

NBThat is true. I hope we don't end up only being in our own countries, cities and homes—I hope the world becomes more open than what we are now experiencing.—[O]