Pak Sheung Chuen

Pak Sheung Chuen. Courtesy the artist.

Pak Sheung Chuen. Courtesy the artist.

Looking around Hong Kong, it's not difficult to imagine how the lack of available space may be skewed in favour of private interests, or how any shifts within the city's densely populated infrastructure directly affect artists. Compounding the challenge many artists face in finding spaces where they can create their work is the city's now 20-year designation as a Special Administrative Region within the PRC: a status, which effectively began in 1997, following the end of more than 150 years of British colonial rule.

Among those responding to how these particular conditions are being felt by Hong Kong's citizens is artist Pak Sheung Chuen. After relocating to the city from China in 1984, Pak has consistently found ways to circumvent the lack of space in the city by rooting his practice in experiences found within daily actions and exchanges that while conceptually based, are keenly felt. Lately, this has manifested in 'an aesthetic pilgrimage of self-healing after the failure of the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong in 2014 [caused] a state of depression that left him devoid of enthusiasm to work.'1

The result has been a marked shift in the artist's artistic approach, which has nonetheless been productive given his work being featured in several exhibitions over the last year and a half. This includes That Light (17 December 2016–26 February 2017) at Vitamin Creative Space's Mirrored Gardens in Guangzhou, which formed the basis of this conversation. His work is also currently being featured in Hong Kong as part of two exhibitions: the group show Tale of Wonderland (19 September–11 November 2017) at Blindspot Gallery and Chris Evans, Pak Sheung Chuen: Two Exhibitions (23 September–3 December 2017) at Para Site. These are among the latest in Pak Sheung Chuen's wide-ranging history of exhibitions, projects, residencies and publications, including serving as the Hong Kong representative at the 53rd Venice Biennale (7 June–22 November 2009).

ICRecently, I read about how your work 'tip-toes on the line where words and images meet, exposing the inhumanity of city life' even as it 'visualises with poetic sensuality [the] habitual and trivial [that] is inscribed on the body.'2

To this I would add how your practice constantly reaches across time and space. This can be seen as the space between yourself and somewhere quite far away, like a building that you are monitoring from across the street where you are standing, but also the time it takes for someone to find you, or for a stranger to call you back. It's telescopic in that sense, and quantifies the distance between you and what you're looking at. Basically, you like to 'take your time' in different ways. Why do you approach your work this way?

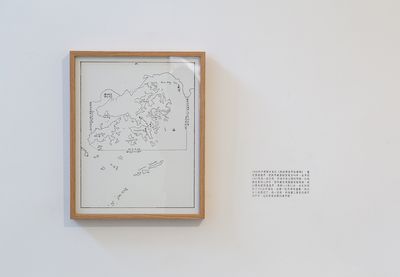

PSCIf you compare the work you saw in my exhibition at Mirrored Gardens in Guangzhou with what I did before, it's a bit different. As you describe, I almost don't need anything. I don't need the production, only the space to show it. I just need the message to come out and be delivered to others and then it's complete. That's the whole working process. But in Guangzhou, you saw some artwork that had form. It's telling or showing some things that made it necessary to present it that way. For example, in Flowing Boundary: The Western Border (113°52'E) (2016), you see the history of Hong Kong through a large stone fountain where a line that can be seen through the waterfall represents the western boundary between Hong Kong and China. I wanted to show this as monumental, to portray the heaviness of this history. So, it's something I tried but not in my normal way or with materials I generally use. This artwork needed it.

ICFlowing Boundary does seem to reference one of the first pieces you made, The Horizon Placed at Home (2004) where you traced another waterline: taking water from Victoria Harbour to recreate a similar view through a row of water bottles in your house. Your fountain does this on a much larger scale, but it's still a way to demarcate a boundary, just in a different form.

PSCVitamin Creative Space has exhibited my work for over ten years, and these two pieces show how I've changed. A decade ago my artwork reflected something different in society and the political situation of Hong Kong. At that time, we didn't need to focus on politics. We focused on everyday things. So when I went out to observe Hong Kong I felt satisfied. I could be very focused on the connection between me and my artwork, and the society at large through this process. I just pointed out different things connecting me with society, and the reader when they came across my work in the newspaper.

ICYour actions are really personal but still bring up a lot for others, like questions about being alone, anxious, or lost. You are not only conscious of the context in which your work is made but in how it's received. How do you feel your work impacts audiences? Do they affect what you create in return?

PSCI always feel ambiguous towards claiming an audience. Even though I do a lot of actions or performances, my creative process is very private. If I do something I feel is interesting, I document that. I make the artwork for myself and then document it to show the audience the process in-between. In my imagination they don't have a relationship. I am not showing myself to people. I am just showing them the documentation.

But that's not right. I do see how there's a relationship because it affects me even though I show the audience the documentation.

ICThis relationship does seem to have changed over time. Before, in pieces like Waiting for a Friend (without Appointment) (2006/2014), you stayed in a MTR station until somebody you recognised showed up. In Waiting for All the People Sleep (2006), you stood in front of a building until all the lights went off, and in Familiar Numbers, Unknown Telephone (2005), you dialled what appeared to be a telephone number at a bus stop, then waited until somebody called you back. But the documentation records a different experience because you eventually met the caller in person. If the idea is to maintain some distance by only showing the documentation, you also use the same work to draw different narratives at other points in time.

PSCLet me speak more about the night I walked around Sham Shui Po and made Waiting for All the People Sleep (2006). I found a building with a lot of people at home since the lights were on in a lot of windows. I just waited there to see how long it would take for all the people to go to sleep. Seeing all the lights turn off was really romantic but when I went to take a picture with my camera I thought something was wrong with the process.

Just this action, this moment of taking the photo affected my entire working process. I thought 'am I doing something for other people or am I doing something for myself?,' and if I am doing something for other people, then something is wrong with me.

For me this issue is also a question about audiences, so I started thinking about how to resolve this in my work. For example, One Day in the Artist's Life (2009) is doing this. In the piece, basically where I spent time with the person who bought the work, I was thinking about collectors who look at my work. They buy my work and I can't neglect them but I don't know them. Even if they do not exist in my imagination, they really do exist and support me, so I am left thinking about what the relationship is between these two roles. I can't totally cut them off, so I made a work to help me get close to them, to understand who they are, and to make what is outside but related to me a part of my artwork.

ICI remember reading elsewhere how in creating this work for the collector, to paraphrase, 'you didn't want them to understand your work but your world'. But there's definitely a big difference between what the artist thinks of their work and how it ends up being received. Also because your work is so much a part of who you are, in some ways you need to be there to really understand it. That's perfect for the collector who gets a sense of you being a part of the work, and while you're creating a personal experience for them as well.

PSCIf we go back to the project about waiting for all the people to sleep. At the end I can do two things to solve my problem: one, I assume that the audience is part of my artwork, minimise the documentation, and just show the people. The other way: I don't visualise anything; I just write the idea down.

So in the past five years I've been writing out ideas like you see on the walls of Mirrored Gardens, minimising everything, to communicate through the text and imagination, and involve the audience. But still I don't feel satisfied.

ICBut your work spending time with a collector is different from waiting for the lights to go off in front of a building. And in another work at Mirrored Gardens, That Two Spots of Light (2016), where you were once again looking at buildings in the distance until only the twinkling lights from two televisions were left—no one knows you're watching them.

PSCIn my process of creating an artwork, I always feel very strongly that I have two roads. One road is I am watching, seeing something. The other road, I am quite clear that I am another person, with people looking at me looking at something. So when you're looking at the two televisions in That Two Spots of Light, the first insight is that I am in the darkness looking at two windows in the darkness.

The people watching TV together don't know each other. But at that moment I know them. I pick them out to show the audience what I am looking at. I am thinking about if in my room there is another audience. Also, who can imagine what I am thinking inside? Basically, I try to bring the audience as close to my situation as I can, to show them what I am thinking and what I am looking at. First, by letting them read all the facts, and then having them interpret what they see in their own way.

ICWell, there is the pairing. The two monitors that can be associated with a pair of eyes and body—your body—looking across at the two buildings.

PSCYes and there are three televisions in the exhibition. A set on the wall and another small television on the floor. These are related to TV Stars (2006), a work from ten years ago and now with a new vision. But the artwork isn't complete until someone stands in my position to look at it.

ICThat's right, in your subject position. I also recall the surrounding wallpaper in the exhibition space that instantly creates—I wouldn't say great intimacy because Mirrored Gardens is quite vast—something to make you feel a hint of the domestic, and as a technique has been used again as part of your current Para Site exhibition. You know you're in a different place.

PSCThat's really the point.

ICThe consistent methodology of using your body in your work gives it a kind of a posture—it's the spine that runs through it—but how do you turn something into an artwork? Where does the work finish and you start?

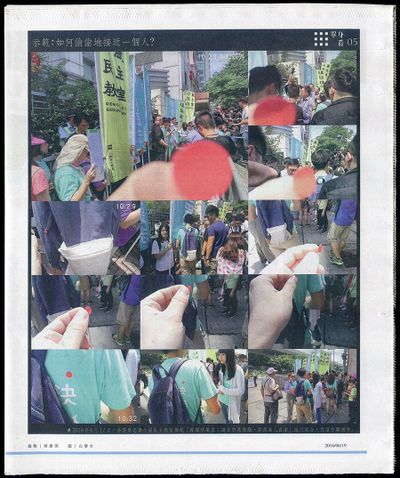

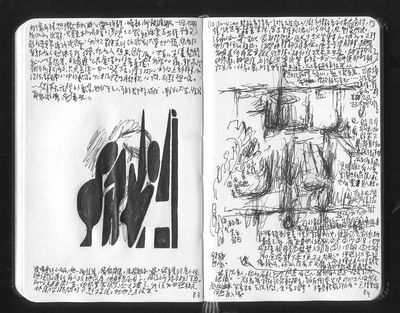

PSCYou mean when do I decide when a work is finished? Because I show people what I am doing. I had a practice for almost ten years, a practice I can show you, but now it's become a sketchbook. Before it was not like that. The Umbrella Revolution led me to this process. Now I write down the idea I see while walking around Hong Kong. I just jot it down. That's really practical when I work on my newspaper column with Ming Pao because they work very fast. Every week I create one project for them and sometimes I need to focus on following their topic to do the artwork.

This is my way of breaking down the whole art making process to observe and connect with the environment. Beyond recent events, I kept this practice every day for almost ten years. I go out, walk around, and then if I see something that gives me some reflection and inspiration, I just jot it down. It's become a habit that I can't stop.

ICIt's almost like exercise, your daily exercise.

PSCIt's also a daily practice that really helps me to fulfill my newspaper job. Every time the newspaper asks me to do something I don't know how to start I just sit down and let the idea come out. I collect a lot of thoughts so it's very easy. I just follow the idea and turn it into something for the newspaper.

For example, the bus stop is not the first piece of the telephone artwork. It's actually the idea I first wrote down in my notebook. It's all related to this daily practice that I keep returning to. I need to walk out and let the environment tell me the story, to have the inspiration between my needs inside and the environment outside synchronised.

ICWhen they synchronise is when it appears in your notebook.

PSCAnd then the idea comes out...

ICAnd then it flows back through the newspaper to even more people.

PSCYes.

ICWhen I look at the newspaper, publications, and exhibition catalogues featuring your work, these all feel like artist books in the way they're formatted and subsequently influence the documentation of your work. Looking at the collection of your published materials and ephemera in two vitrines at Mirrored Gardens, or the continuation of this process in your current Para Site exhibition, how does this fit into your long-term affiliation with art in print and the Hong Kong newspaper Ming Pao as a weekly contributor?

PSCI had just graduated when I started with the newspaper, so this was my only chance to show my artwork. But I also wanted to test the newspaper, to find its limitation and see if I could express my ideas or emotions through it or not. I understand how artwork being presented to the reader in this way is not totally easy work. If you think that just putting an image inside of the newspaper completes the work you won't last long.

I did this for five years and now again for almost ten years. Within this timeframe I have not only thought about how to use the newspaper as a forum for my artwork but more broadly, like how it can reach more people and about the newspaper as a means of communication. My earlier artwork in the newspaper was similar to advertising. It gave a very strong point of view that people remembered and then looked for something new to appear next week. This is my strategy. So, the newspaper for me is an art medium, not only something to document my artwork but a medium. But when I turned the collection of my work in the newspaper into a book that was something else.

ICI'm curious how you were invited to contribute to the newspaper. They don't often work directly with artists, but they continue to publish you so obviously like it, and their audiences clearly find something interesting about your work, but it's unusual. Has anything changed over the years?

PSCIn the beginning the newspaper was important because what I was making was new and something that never happened in Hong Kong. I also found this process totally fit my lifestyle. It was only before I went to New York for a residency that my editor said I might need to stop, and after four years I needed to stop. The format had become too familiar and I wanted to try something different so I began showing my artwork in museums.

I was also limited by some topics, not because of 'freedom of expression' but, for example, something violent, something sexual, it's not suitable for the Sunday newspaper. The newspaper also has a position to show what's suitable. But mostly, I had tested almost every way of presenting my work and just wanted to try something new. In the end, I stopped for a few years but when I went to New York I made a five-issue series for them again. But by the second issue my editor said that they couldn't show it, although in the end they did.

ICWas it the first time this happened to you?

PSCYes, the first time, but why it happened is because I wasn't in Hong Kong so was not using the way people think about the situation here. I just expressed what I was thinking in New York, which was to go to the library and draw some books, then tear and dog-ear the pages, and show this as a project. I felt very confident about this project because it was connected with my life in New York: the loneliness I felt since no one knew me, and I wanted to make a mark in the city, having seen a lot of graffiti. So I made the piece very naturally and didn't think that there was a problem but the newspaper received lots of complaints!

ICThat you were ruining the books?

PSCYes, and with over ten letters complaining to the editorial board. It was very frustrating because this was the first time I felt how distant the audience was from me. Even though it was very mild, by publicly showing that I was doing something illegal inside the library I'd crossed some taboo that shouldn't be touched in Hong Kong's public newspaper. But today, after the Occupy Movement, thinking about the city is very different.

ICI would say that unlike other journalists or contributors your relationship with Ming Pao is different because they know your column is art and yet they want it there. It's uncommon that established publications would allow for an artist's work within their pages and especially for such a long duration with little concern over the content.

PSCAlthough the publishing world is changing. I can feel the affect of print is now much less than ten years ago, now that people go to Facebook or Twitter.

Would you do digital work?

I did some things but I don't like having 10,000 people acting fast on one issue. You need to have a very clear point going out and react very fast but there's no need to be deep, or to think. I don't like working that way. In the newspaper you can still use one week to think about the whole issue and how it will come out. Facebook can't do that.

ICI read somewhere recently that for millennials, 'the headline is the news'.

PSCYes, Facebook is just the headline. No one needs to look deeply. It sounds good and we like it, that's it.

ICSince we're discussing forms of social mediation, if you look at what's happening in terms of social practice—these days, a lot of art includes some form of personal interaction. Some artists need the group to create their artwork but yours is sparked by daily action; something you could say is a form of social practice. How do these interactions affect you? What meaning do you think it has for people?

PSCI think sometimes I don't need to do exhibitions, especially when I participated in the Umbrella Revolution. At that moment, I found that Facebook helped me, even though I don't really use social media in my work. Facebook helped me release my point along with some photos. I could reach a lot of people.

ICSometimes the art isn't necessary ...

PSCI always focus on my own situation. This includes the situation around me, but I use my own interpretation to express it. In fact, when I found sometimes that I failed to interact with my environment, I just showed these failures in my artwork. It's more accurate.

ICWell, many other artists can't represent those situations as closely as you because your practice already involves you being 'out there' in the city. So even if you're protesting you're applying that same action only with a different purpose. But when do you choose to articulate this as a civilian and not as an artist? I guess it depends on your vision of what the outcome is supposed to be. Maybe it's better for the artwork to produce a sense of failure if it then inspires people to seek some other means of defining success whether as an artist or a civilian.

In terms of choosing an approach, there are elements of performance, video, and sculpture in your work, but none of them seem individually appropriate. I thought of the term 'conceptual anthropologist' but how do you define yourself as an artist?

PSCI never need to claim the title of 'artist' but what I am doing is something that I feel is important and meaningful. I think it is closer to a life form—not a life art but a life form I use in a lot of ways to present my thinking, my ideas, and my emotions. The term artist can represent me, but I'm not really a performance artist. I have ideas but I wouldn't call myself a conceptual artist. I do interact with the environment around me with my body. Even as I talk with you now, this interview is a part of it.

ICSo you'd like to stay non-categorised.

PSCArtist is fine. And human. –[O]

—

—

—

1 Press release from Chris Evans, Pak Sheung Chuen: Two Exhibitions (23 September–3 December 2017) at Para Site in Hong Kong.

2 Visual/Textual City: See Walk What on 1 July, back cover.